Birth

Date unknown, between 1300-1100 BC

Death

Date unknown, between 1300-1100 BC

The Skrydstrup Woman lived during the European Nordic Bronze Age over 3000 years ago. Her oak-coffin grave was found near Skrydstrup, Southern Jutland, in 1935. The woman was seventeen or eighteen years old at the time of her death. Her discovery and further study show that women, not just men, were mobile during this time.

Personal Information

Name(s)

The Skrydstrup Woman (archaeological name given to her based on the place she was found/buried), hence given name unknown (e.g. Broholm and Hald 1939; Aner and Kersten 1984; Jensen 2002; 1998; and online links).

https://slks.dk/index.php?id=21330

Date and place of birth

She lived during the European Nordic Bronze Age over 3000 years ago. Recent radiocarbon analyses of her scalp hair yielded an age between 1382 and 1129 cal BCE (Frei et al. 2017).

Her place of birth is unknown, however, based on the recent strontium isotope analyses of tooth enamel of one of her first molars, the results indicate that she was non-local and potentially came for afar with respect to the place that she was buried (Frei et al. 2017). Furthermore, by combining the biological profile investigations with that of the results yielded by the multi-strontium isotope analyses on her teeth and long scalp hair (measuring over 60 centimetres), researchers were able to reconstruct a detailed timeline of the Skrydstrup Woman’s mobility during her life. These investigations suggest that the Skrydstrup Woman migrated to the Skrydstrup area in present-day Denmark (southern Scandinavia) when she was between 13 to 14 years old from a place outside present-day Denmark (Frei et al. 2017, and for further info on the topic see below).

While is very difficult to pinpoint potential areas of origin for the Skrydstrup Woman, the closest areas to present-day Denmark that seem to meet baseline ranges that include the high strontium isotope signatures as the ones measured in the Skrydstrup Woman’s tooth enamel include: to the south, middle-eastern Germany, northeastern Netherlands, and northeastern Czech Republic; to the north, southern Sweden; and to the west, some areas in Britain.

After her displacement (ca. at age between 13 to 14 years old), the strontium isotope analyses suggest that she resided in the area around Skrydstrup for the rest of her life.

The studies of the Skrydstrup Woman represent the first time that scientists have been able to identify, the age in which an exceptional well preserved prehistoric individual migrated (Frei et al. 2017).

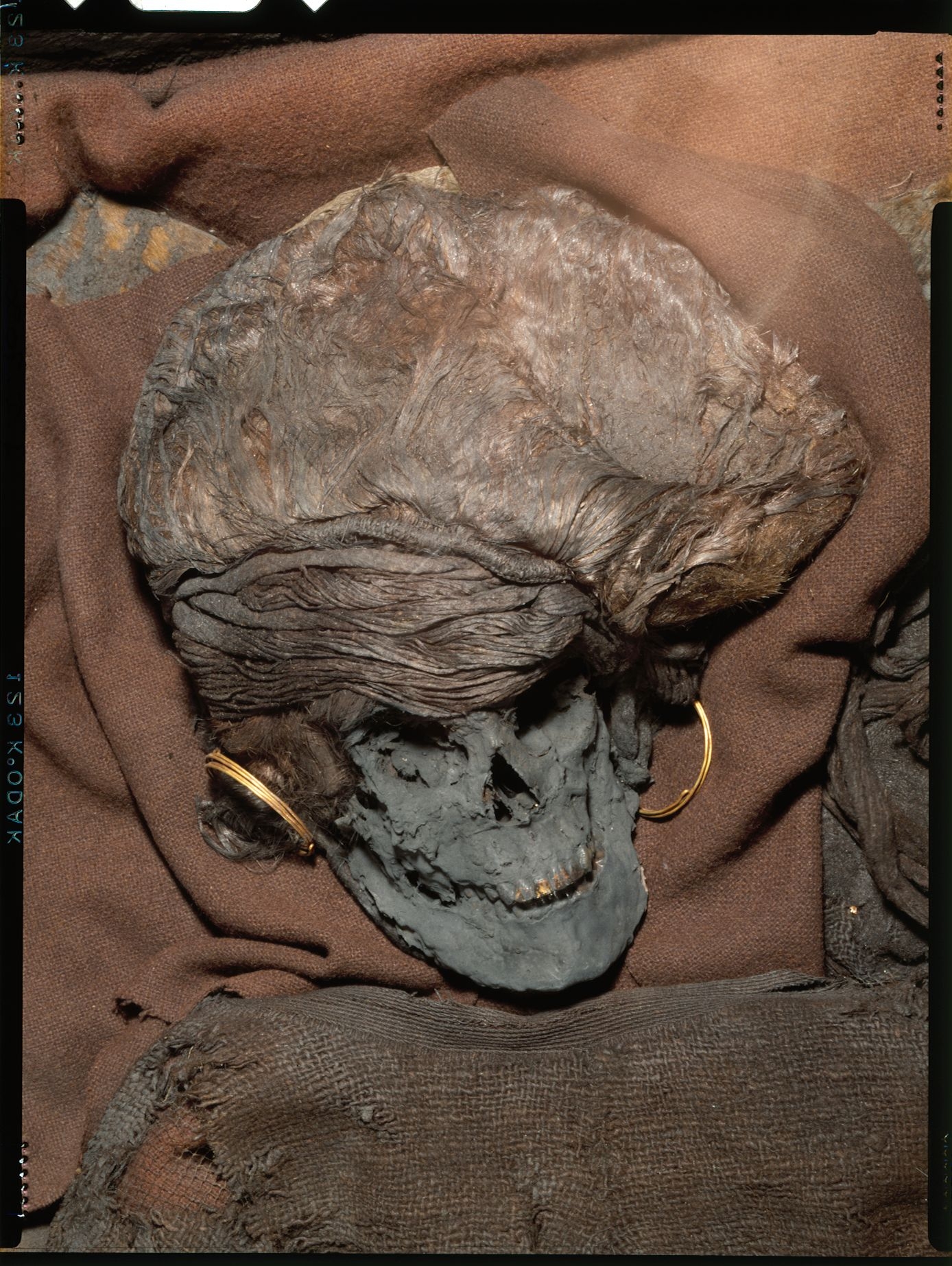

Alive, the Skrydstrup Woman would have been striking. She was approximately ten centimetres taller than most other women at the time. Additionally, the Skrydstrup Woman featured a highly complex hairstyle. In order for her locks to be set, her hair was first combed forward and downwards over a hair pad before being bound by a wool cord (Broholm and Hald 1939; Broholm and Hald 1940). The hair was then plaited across the forehead from temple to temple before finally being covered with a hairnet that seems to have been made from horse hair. This elaborated hairstyle, which would have added further some centimetres to her already impressive height.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0178834

Death and place of death

The cause of death is unknown. She was buried inside a monumental burial mound (ca. 13 meters in diameter and 1.75 meters in high), probably inside an oak-coffin, both of which are indicative of that she belonged to the elite. The recent physical anthropological analyses rendered an estimated age at death of 17–18 years.

The Skrydstrup woman’s remains represent the monumental burial mound’s primary grave and consisted (at the time of her discovery) of skeletal as well as soft tissues including parts of her cheeks and chin, eyebrows, eyelids, eyelashes and her long hair.

The investigations conducted of her skeletal material, hair, teeth, and nails do not reveal that she might have suffered from a prolonged period of illness or malnutrition. Hence, there have been speculations that she might have suffered a relative rapid death due to for example an infection.

Her hair measures in at over 60 cm, and it was set in a very complex and elaborated hairstyle.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0178834

Family

Unknown. However, ancient DNA (aDNA) analyses have been attempted on a small hair sample which unfortunately showed not to be sufficient to conduct aDNA analyses as the sample only yielded a very low DNA concentration.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0178834

Marriage and Family Life

While based on the archaeological context finds, as well as the results of the recent scientific analyses made in the human remains, speculations have been made regarding the reason of her migration to the area of present-day Denmark.

From an archaeological standpoint, this one-time and one-way movement of an elite female during the possible (at the time) “age of marriageability” suggests that she might have migrated with the aim of establishing an alliance between chiefdoms through a kind of marriage relationship (Reiter and Frei 2019). Still, there are also other possibilities that should be considered. Some scholars suggest that Bronze Age women played a bigger and central role also in network-related issues.

While she was buried central in the monumental burial mound, two (probable males) where buried one each of both sides of her (Frei et al. 2017).

Based on the physical anthropological analyses it could not be determined whether she had given birth or not (Frei et al. 2017).

http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Moralia/Bravery_of_Women*/A.html

Education

While her burial (central in a monumental mound) and her grave goods (including golden earrings, embroider garments, etc.,) testify of her being part of the elite, her skeletal remains (e.g. tooth enamel) and hair, testify of well nutrition during her life. These aspects indicate that she belonged to the elite, and her mobility suggests that she was part of the European Bronze Age Network.

Religion

The Nordic Bronze Age people probably imagined that the soul followed the sun around on its journey across the sky and through the underworld by night (e.g. Kaul 1998, 2004). Each morning the soul was reborn along with the sun. Perhaps it was thought that some of the dead were given an honorable, sacred role as part of the crew of the Sun Ship. In this way the dead helped to ensure that the sun moved along on its eternal journey.

The Sun Chariot which was found in September 1902 in Trundholm bog in northwestern Zealand, Denmark, is one of the most iconic symbols of the Nordic Bronze Age religion (The Sun Chariot is today featured in the 1000 Danish krone banknote). The Sun Chariot was made in the Early Bronze Age around 1400 BCE and relatively contemporaneous with the Skrydstrup Woman. The elegant spiral ornamentation that graces the golden sun disc reveals its Nordic origin. The Sun Chariot illustrates the idea that the sun was drawn on its eternal journey by a divine horse (Kaul 2004). A sun image and the horse have been placed on wheels to symbolize the motion of the sun.

Females seem also to have played a role in ritual activities. The burials of other Bronze Age females, like the Egtved Girl or the Ølby Woman, revealed that they were wearing the so-called short “corded skirts” which were made of wool. Some of these corded skirts also consisted of having small bronze tubes around the wool cords, which would have made a “chiming-like” sound when the women moved. The short corded skirts are also seen depicted on small bronze figurines as well as depicted in rock art in which seems to be related to ritual activities. Hence, scholars have suggested that women wearing “corded skirts” might have been Sun-priestesses.

Bronze Age “lurs” which are thought to have been used in connection with rituals have been found in the area where the Skrydstrup Woman was buried. A “lur” or “lur horn” is a wind (musical-like) instrument cast in bronze dating to the Late Bronze Age (c. 1000 BC). Most of the Bronze Age “lurs” have been found in Denmark (ca. 40). Still, also some have been found in Sweden, Norway and northern Germany. In Denmark the lurs are usually found in pairs and in bog deposits. On Swedish rock carvings from the Bronze Age one can see lur-blowers who seem to be participating in processions or religious rites.

The Skrydstrup Woman herself was wearing a very long wool skirt (Broholm and Hald 1939; Broholm and Hald 1940), and while one can assume that she was probably familiar with the Nordic Bronze Age rituals, we do not know about her personal relation to such rituals.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1600-0390.2017.12176.x

https://www.rockartscandinavia.com/images/articles/a12kristiansen.pdf

less

Significance

We can’t, for obvious reasons, know how her intellect was, nevertheless judging from the way she was buried -central in the monumental mound with valuable grave goods- and by the importance of the Skrydstrup area at the time (see below), there is no doubt that she represents an individual of social and cultural significance. She also seems to have been respected and assimilated (at least partially) into the local society despite her non-local origin.

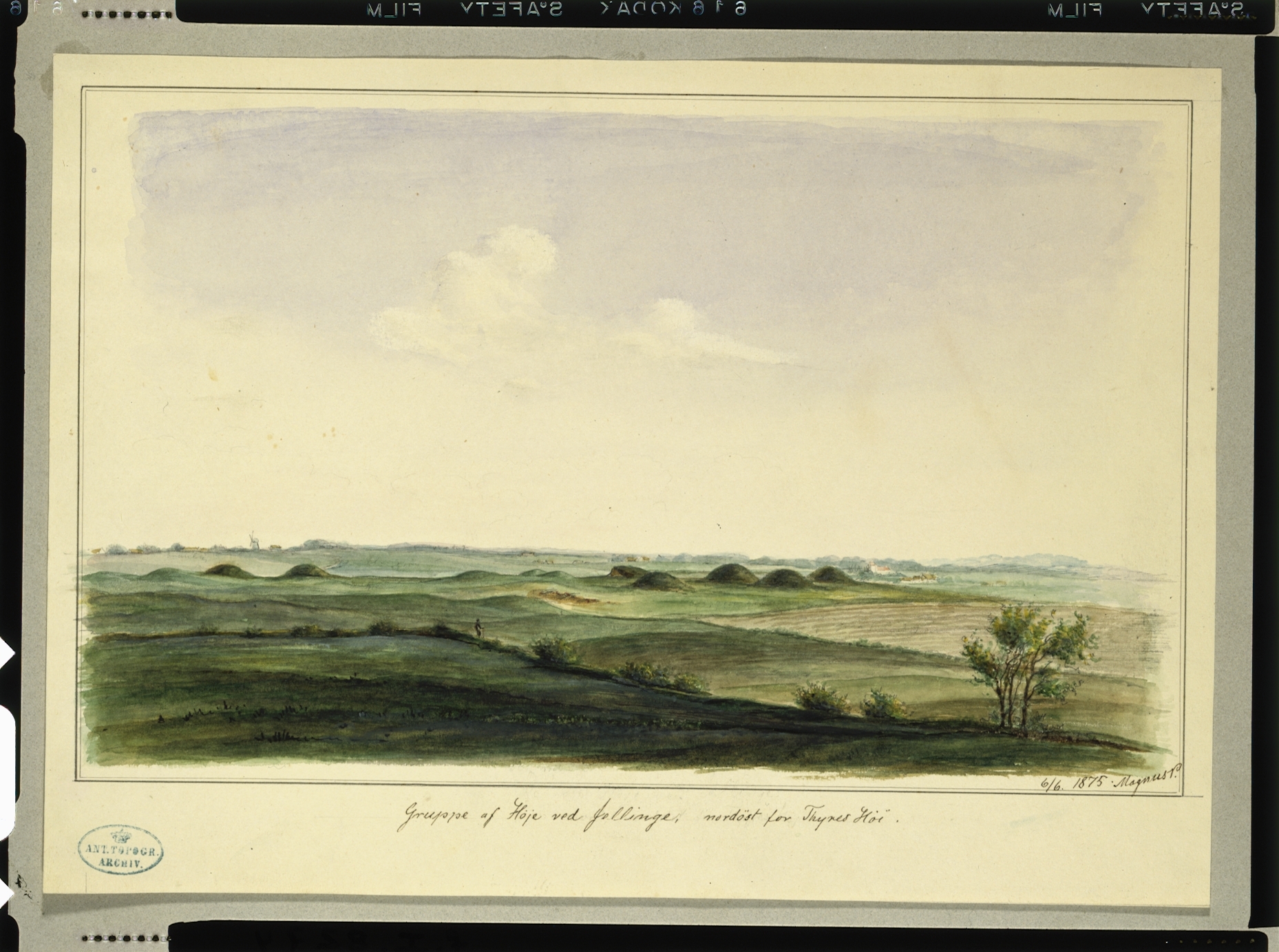

Interesting for the archaeological context of the Skrydstrup Woman’s burial is: i) a contemporary settlement of longhouses nearby which were discovered in 1993 as well as, ii) the location of the burial site near a central trade route (Ethelberg 2000). The longhouses discovered in 1993 are located about 600 meters to the east of the burial site and consist of three 3-aisled structures, which according to the radiocarbon dates, are contemporary with the Skrydstrup Woman’s burial mound-group and therefore potentially suggests some kind of relationship. Furthermore, one of the houses (House IV) exhibited an impressive total ground area of approximately 500 m2, making it the largest Early Bronze Age house excavated in Denmark to date (a size comparable to the Viking Age Royal Halls builded in Denmark ca. 2000 later), indicating the importance of this area during the Early Bronze Age.

In sum, the impressive size of this longhouse, combined with its proximity to the central trade route (known as the “Hærvej” in Danish) provide evidence of this area’s important role in interregional trading networks during the Nordic Early Bronze Age (most specifically in Periods II and III). The fact that the Skrydstrup woman was buried in a monumental mound within the above mentioned context provides evidence of her being an individual of social and cultural significance.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0178834

https://oldtidsglimt.dk/location/skrydstrupkvindens-bolig-og-grav/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L2HDHrf5bcc

Works/Agency and Contemporaneous context and Networks

The Skrydstrup Woman was unearthed in 1935 from a monumental burial mound in southern Denmark. The mound from which she was recovered was part of a mound-group located southwest of the village of Vojens in a geographical central line that divides the landscape in two by the end-moraine in the Jutlandic peninsula which stretches from south to north and dividing the landscape. To the west, the land is flat and sandy, whereas to the east the landscape is dominated by hills and easily recognizable moraines. This natural geographical and geological zone rans parallel to central trade/exchange route in ancient times (also known in Danish as the “Hærvej”) and passed very close to the Skrydstrup site.

https://www.visithaderslev.dk/haderslev/planlaeg-din-tur/skrydstrupkvindens-grav-gdk952465

Transformation

Until recently, the most widespread theory was, that human mobility during the Nordic Bronze Age was very restricted and in the cases where human mobility was present, it was mostly male warriors who moved (e.g. Jensen 2002). However, the recent investigations which started with that of the Egtved Girl (Frei et al. 2015) followed by that of the Skrydstrup Woman (Frei et al. 2017), suggest that Women too could be mobile. This emerging new knowledge has since also been corroborated by others scientific studies elsewhere in Europe for example in Germany (Knipper et al. 2017). In the German study the authors conclude that: “The results also attest to female mobility as a driving force for regional and supraregional communication and exchange at the dawn of the European metal ages” (Knipper et al. 2017).

Over all, this novel awareness has provided a new dimension in which to re-interpret socio-dynamics in the past, as well as it has raised questions regarding the “power” that women might have had at the time.

New and unfolding information and interpretations. Meaning or significance, both for our understanding of her and as modifications for existing representations.

And Critiques of existing/experiments with new knowledge-ordering systems.

There has been some scholarly debate as to how strontium isotope analyses from prehistoric human remains should be interpreted within Denmark with respect to the Danish baseline (e.g. Price 2021; Thomsen and Andreasen 2019; Frei, Frei, and Jessen 2020). Suggestions regarding the proper choice of proxies to construct such baselines and their relevance with respect to human mobility studies have been put forward (e.g. Price 2021; Frei, Frank, and Frei 2022).

The baseline debate has also touch upon the interpretation of the strontium isotope results from the Skrydstrup woman (Frei et al. 2017). Still, the most recent baseline studies (Price 2021; Frei, Frank, and Frei 2022) are in support of the interpretation that the Skrydstrup woman was mobile and that she was non-local.

Legacy and Influence

Since the Skrydstrup Woman was excavated in 1935 by the local Museum (Haderslev Museum), she has been of interest to the archaeologists as well as to the general public. She has become one of the “identity” symbols of the region.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L2HDHrf5bcc

https://graenseforeningen.dk/om-graenselandet/leksikon/skrydstrup-pigen

Contemporary Identifications

Bronze Age women could also be powerful and travel.

Other ancient female biographies

From the Nordic Bronze Age (from Denmark):

The Ølby Woman

https://tidsskrift.dk/dja/article/view/114995

The Egtved Girl

https://www.nature.com/articles/srep10431

https://www.rockartscandinavia.com/images/articles/a15felding.pdf

From Egypt (contemporaneous with the Nordic Bronze Age):

Hatshepsut, (first female pharaoh who reigned in her own right c. 1473–58 BCE and who attained unprecedented power for a woman).

less

Controversies

As mentioned above, there has been some scholarly debate as to how strontium isotope analyses from prehistoric human remains should be interpreted within Denmark with respect to the Danish baseline (e.g. Price 2021; Thomsen and Andreasen 2019; Frei, Frei, and Jessen 2020). However, the most recent baseline studies (Price 2021; Frei, Frank, and Frei 2022) are in support of the interpretation that the Skrydstrup woman was mobile and that she was non-local.

New and unfolding information and/or interpretations

The Tales of Bronze Age Women/Tales of Bronze Age People research team is currently working on a re-evaluation of gendered mobility patterns in later European prehistory which will include data from the Skrydstrup Woman as well as other males and females from this period in order to re-assess current scholarly models about how men and women may have been mobile at this time as well as their roles.

less

Bibliography

Bibliography:

Aner, E., and K. Kersten. 1984. Die Funde der älteren Bronzezeit des nordischen Kreises in Danemark, Schleswig-Holstein und Niedersachsen, Nordslesvig – Nord, Haderslev Amt. Vol. 7. Neumünster: Wachholtz Verlag.

Broholm, H. C., and M Hald. 1939. Skrydstrupfundet. København: Nordisk Forlag.

Broholm, H.C., and M. Hald. 1940. Costumes of the Bronze Age in Denmark. Copenhagen and London.

Ethelberg, P. 2000. Bronzealderen. In Det sønderjyske landbrugs historie. Sten- og Bronzealder. Haderslev: Historiske Samfund for Sønderjylland.

Frei, Karin Margarita, Ulla Mannering, Kristian Kristiansen, Morten E. Allentoft, Andrew S. Wilson, Irene Skals, Silvana Tridico, Marie Louise Nosch, Eske Willerslev, Leon Clarke, and Robert Frei. 2015. Tracing the dynamic life story of a Bronze Age Female. Scientific Reports 5:10431.

Frei, Karin Margarita, Chiara Villa, Marie Louise Jørkov, Morten E. Allentoft, Flemming Kaul, Per Ethelberg, Samantha S. Reiter, Andrew S. Wilson, Michelle Taube, Jesper Olsen, Niels Lynnerup, Eske Willerslev, Kristian Kristiansen, and Robert Frei. 2017. A matter of months: High precision migration chronology of a Bronze Age female. Plos One 12 (6):e0178834.

Frei, R., K. M. Frei, and S. Jessen. 2020. Shallow retardation of the strontium isotope signal of agricultural liming - implications for isoscapes used in provenance studies. Science of The Total Environment 706:135710.

Frei, Robert, Anja B. Frank, and Karin M. Frei. 2022. The proper choice of proxies for relevant strontium isotope baselines used for provenance and mobility studies in glaciated terranes – Important messages from Denmark. Science of The Total Environment 821:1-13.

Jensen, J. 1998. Manden i Kisten. Hvad bronzealderens gravhøje gemte.: Gyldendal.

Repeated Author. 2002. Bronzealder 2.000-500 f.Kr. 4 vols. Vol. 2, Danmarks Oldtid. København: Gylndendalske Boghandel.

Kaul, F. 1998. Ships on Bronzes: A Study in Bronze Age Religion and Iconography. Vol. 3, Studies in Archaeology & History. Copenhagen: National Museum of Demnark.

Repeated Author. 2004. Bronzealderens religion: studier af den nordsike bronzealders ikonografi: Det Kongelige Nordsike Oldskriftselskab.

Knipper, Corina, Alissa Mittnik, Ken Massy, Catharina Kociumaka, Isil Kucukkalipci, Michael Maus, Fabian Wittenborn, Stephanie E. Metz, Anja Staskiewicz, Johannes Krause, and Philipp W. Stockhammer. 2017. Female exogamy and gene pool diversification at the transition from the Final Neolithic to the Early Bronze Age in central Europe. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Price, T. Douglas. 2021. Problems with strontium isotopic proveniencing in Denmark? Danish Journal of Archaeology 10:1-12.

Reiter, Samantha S., and Karin M. Frei. 2019. Interpreting Past Human Mobility Patterns: A Model. European Journal of Archaeology 22 (4):454-469.

Thomsen, Erik, and Rasmus Andreasen. 2019. Agricultural lime disturbs natural strontium isotope variations: Implications for provenance and migration studies. 5 (3):eaav8083.

Web resources

This research wan one of the most prestigious international archaeological research awards: The Shanghai Archaeological Forum Research Award 2017:

http://www.kaogu.cn/en/International_exchange/Academic_activities___/2017/1211/60355.html

http://www.kaogu.cn/en/Special_Events/disanjieshanghailuntan/2017/1214/60412.html

http://shanghai-archaeology-forum.org/index.php/2017-saf-r10/

Comment

Your message was sent successfully