Birth

December 17, 1706

Death

September 10, 1749

Émilie Du Châtelet was one of the most important natural philosophers of the 18th century. Her work draws on the Continental rationalist tradition, including Descartes, Leibniz, and Wolff, as well as on the British empiricist and experimental tradition, including Locke and Newton. Her main work, the Institutions de Physique, was published in 1740. She also wrote on happiness, society, physics, mathematics and mechanics, and she is the first translator and commentator of Newton's Principia.

Personal Information

Name(s)

Gabrielle-Émilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil

Name after Marriage: Gabrielle Émilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil, Marquise Du Châtelet-Laumont

Date and place of birth

December 17, 1706, in Paris, France

Death and place of death

September 10, 1749, in Lunéville, France

Family

Émilie was the only daughter of Gabrielle Anne de Froullay, Baronne de Breteuil, and Louis Nicolas le Tonnelier de Breteuil. The couple had six children, though only three of their sons reached adulthood. Émilie also had a half-sister called Michelle through her father. Little is known about Émilie’s mother, Gabrielle-Anne, though it seems she was a more serious person, or at least appears to have enjoyed a less opulent lifestyle, than her husband. This may have resulted from her childhood: she was raised in a convent, which was de rigueur for aristocratic young girls in France at the time.

Being a member of the lower nobility, Émilie’s father was a high-ranking official at the Court of Louis XIV and held the title Introducteur des Ambassadeurs. Though not a noted intellectual, he did hold a regular salon at the family home, which was attended by respected scientists and writers.

Childhood & Education

Recognizing his daughter’s potential at an early stage, Émilie Du Châtelet’s father was determined that she should receive an excellent and comprehensive education like her brothers. There is much debate concerning Emilie’s mother’s position regarding her daughter’s education. Having been brought up in a convent and aware of the position of women at that time, some historians argue that she may have disapproved of her daughter’s intellectual prowess. However, in other accounts, she also seems to have encouraged the young Émilie’s thirst for knowledge.

Émilie’s father arranged for private tutors for her and she thus received an excellent education. At an early age she was already fluent in both Greek and Latin, as well as Italian and German and was tutored in mathematics, science, and literature. At fifteen, she translated Vergil into French. She was passionate about music and opera and liked to dance. As a young child, her father also organised tutors for riding, fencing, and gymnastics. One of her favourite hobbies was playing cards, and she later used her mathematical skills to devise elaborate strategies for gambling.

One of the people present at Émilie’s father’s salons during Émilie’s youth was Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle, a noted scientist in the Académie Francaise and a prominent figure in the age of Enlightenment; he was introduced to Émilie at the age of ten. He tutored her on topics in philosophy and science. The young Émilie excelled in languages, mathematics, philosophy, and the natural sciences, all of which she later put to use in her own work.

Marriage and Family Life

On June 12, 1725, nineteen year-old Émilie Du Châtelet married the Marquis Florent-Claude Du Châtelet-Laumont, who was fifteen years her senior. As was common in France at that time, her marriage was arranged. As a wedding gift from her father-in-law, her husband became governor of Semur-en-Auxois in Burgundy. The couple had three children together: Francoise-Gabrielle-Pauline, Louis Marie Florent and Victor-Esprit, who died at the age of one. The Marquis was not a match for Du Châtelet’s intellectual abilities and passions, and the marriage was never more than a consensual arrangement. Consequently, Du Châtelet joined the court in Versailles where she enjoyed the lavish lifestyle of an aristocratic member of the Queen’s circle, buying expensive clothes, enjoying theatre and the opera, and in search of a romantic, passionate, and intellectually stimulating relationship. She had come to an amicable arrangement with her husband by this time.

Soon after the birth of her third child, a relationship with the writer Voltaire led the young Du Châtelet away from her husband and children. However, she continued to invest in the education of her children from her marriage with Du Châtelet-Laumont, especially in the education of her son. In the 1740 foreword to the Institutions de Physiques, which is dedicated to her son, she writes:

“I have always thought that the most sacred duty of men was to give their children an education that prevented them at a more advanced age from regretting their youth, the only time when one can truly gain instruction. You are, my dear son, in this happy age when the mind begins to think, and when the heart has passions not yet lively enough to disturb it" (Inst1740eZ, §1).

Although Du Châtelet invested most of her educational efforts into her son and not her daughter, likely due to societal or individual constraints, she was an avid advocate for women’s education. In the editor’s preface to her translation of Mandeville’s Fable of the Bees she writes:

“As for me, I confess that if I were king I would wish to make this scientific experiment. I would reform an abuse that cuts out, so to speak, half of humanity. I would allow women to share in all the rights of humanity, and most of all those of the mind. Women seem to have been born to deceive, and their soul is scarcely allowed any other exercise. This new system of education that I propose would in all respects be beneficial to the human species. Women would be more valuable beings, men would thereby gain a new object of emulation, and our social interchanges which, in refining women’s minds in the past, too often weakened and narrowed them, would now only serve to extend their knowledge.”

Du Châtelet clearly saw womens’ education as an ideal that should be put into political practice, while she herself did not dedicate her life to this project but to her own writings, for she adds:

“Some will probably recommend that I ask M. the abbé of St. Pierre to combine this project with his. Mine will perhaps seem as difficult to put into practice, even though it may be more reasonable.”

Du Châtelet saw the lack of education, and not of talent or capacity, to be at the root of women being excluded from intellectual matters. In the same preface to the Fable of the Bees she writes:

“I feel the full weight of prejudice that excludes us [women] so universally from the sciences, this being one of the contradictions of this world, which has always astonished me, as there are great countries whose laws allow us to decide their destiny, but none where we are brought up to think. […] Let us reflect briefly on why for so many centuries, not one good tragedy, one good poem, one esteemed history, one beautiful painting, one good book of physics, has come from the hands of women. Why do these creatures whose understanding appears in all things equal to that of men, seem, for all that, to be stopped by an invincible force on this side of a barrier […].”

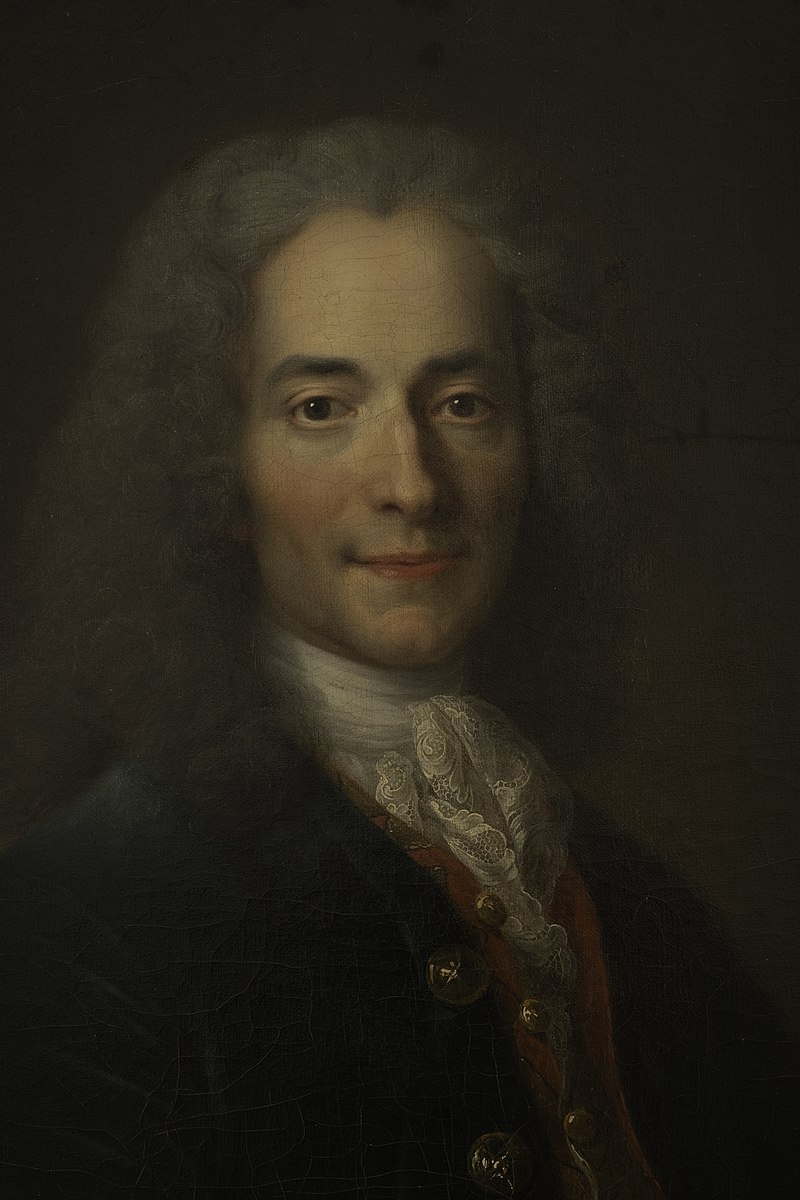

Voltaire (François-Marie Arouet):

There are references which claim that Du Châtelet first met Voltaire at one of her father’s salons when she was still a child, while Voltaire himself dates their first meeting to 1729. Regardless of the exact date of their first encounter, it is evident that as of 1733 Du Châtelet and Voltaire had developed a close friendship, which quickly turned into a passionate romantic and intellectual relationship. When Voltaire was looking to escape censorship and religious persecution in Paris, Du Châtelet offered to let him live in one of the family’s empty castles in Cirey. Du Châtelet and Voltaire renovated the castle together and lived there for fifteen years, in which they worked together intensely. Their work was very productive, but it was also marked by disputes and dissents. Du Châtelet has long been portrayed as Voltaire’s “mistress”, but we now know that this supposition can also be viewed the other way around: Voltaire was certainly an inspiration for Du Châtelet, however she disagreed with him on many matters, and consequently went on to write her own works. Under Du Châtelet and Voltaire, Cirey became a renowned centre of science, housing scientific equipment and an expansive library, which Du Châtelet developed. Many esteemed members of intellectual circles visited Du Châtelet and Voltaire, including luminaries such as Pierre Louis Maupertuis, the Bernoulli brothers, and Francesco Algarotti. Du Châtelet entertained a long correspondence with Maupertuis and Bernoulli II. All of the guests, who sometimes stayed for considerable periods of time, marvelled at the Marquise Du Châtelet who, as well as excelling in intellectual matters, held extravagant parties and was an excellent hostess.

In papers purchased by Catherine the Great after Voltaire’s death, it is clear that Du Châtelet had a strong influence on Voltaire and supported him in writing Eléments de la philosophie de Newton, published in 1738. Voltaire writes in the foreword that he is indebted to Émilie Du Chatelet for her help. In a 1735 letter to Algarotti, Du Châtelet herself stressed that she was the more scientific member of the partnership. Later, Du Châtelet criticised the lack of metaphysics in Voltaire’s work. Shortly after the publication of Voltaire’s Eléments de la philosophie de Newton, Du Châtelet published her Lettre sur les Élements de la Philosophie Newton (1738).

Voltaire and Du Châtelet’s romantic relationship ended when Voltaire left her to begin a relationship with his young niece, Marie-Louise Mignot Denis, however they remained indebted to each other until the end of Du Châtelet’s life. Voltaire was present at Du Châtelet’s untimely death and wrote to the writer Mme au Boccage:

“I have just arrived in Paris, madam: the greatness of my sorrow and my wretched health shall not prevent my at once assuring you how deeply I feel your kindness. A mind as noble as yours must needs regret such a woman as Mme. du Châtelet. She was an honour to her sex and to France. She was to philosophy what you are to literature […].”

Despite Voltaire’s praise, it is not likely Voltaire ever recognised Du Châtelet’s achievements in their magnitude, for he writes after her death:

“[…] and although she had just translated and simplified Newton – that is to say, done what, at most, three or four men in France would have dared to attempt – she regularly cultivated, by reading lighter books, the splendid intelligence which nature had given her.”

Voltaire’s reduction of her achievements to a ‘translation’ and ‘simplification’ of Newton stems from Du Châtelet and Voltaire’s disagreement on the importance of metaphysics, the significance of the philosopher and mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, and their differing views on Newton’s physics. Du Châtelet writes in the foreword to the Institutions physiques:

“You can draw much instruction on this subject from the Eléments de la philosophie de Newton [Voltaire’s Elements of the Philosophy of Newton], which appeared last year. And I would omit what I have to tell you about that—Newton’s system—if the illustrious author had embraced a vaster terrain; but he confined himself within such narrow boundaries that he made it impossible for me to dispense with my own exposition of this matter.”

Du Châtelet considered self-idolatry just as harmful as the idolatry of others. She repeatedly emphasises her love for the truth and being right, and warns her son that the search for truth must prevail over partisanship, taking sides in disputes or self-esteem. She thought that each science surpasses the powers of a single person and that the individual scientist helps erect the building of science. However, it must not be overlooked that in her metaphor she considered herself an overlooker and architect of science, rather than just a builder laying stone. Among her passages dismaying at a lack of talent or genius, we also find her saying:

“I am my own person and only responsible to myself for everything I am, what I say, and what I do. There may be metaphysicians and philosophers whose knowledge is greater than mine. I haven’t met them yet. But even they are only weak human beings with faults, and when I count my gifts, I think I may say that I am inferior to none.” (Letter to Frederik the Great, 1740)

Jean-Francois de Saint-Lambert:

At forty-two, Émilie Du Châtelet began what was to be her last relationship with Jean-Francois de Saint-Lambert, a little known poet and military officer eleven years her junior. Du Châtelet writes to him:

“You will see that this joy of the armistice, the pain of being far from you, fills my heart with so much pain and so much joy that it succumbs from being torn apart. But I am dying of lassitude, I do not have the strength to write, I have only that to love.”

Without intention, she became pregnant and was worried that she would not survive the birth of the child, endangering her son’s heritage. She gave birth to a daughter, Stanislas-Adélaïde, on September 4, 1749. The birth appeared to go well but six days later, surrounded by her husband, Voltaire, and Saint-Lambert, Émilie du Chatelet died in Lunéville. Her newborn baby died in infancy at just one year of age.

Contemporary Identifications

Duke University awards an annual Du Châtelet Prize in the Philosophy of Physics to a graduate student essay in the philosophy of physics. The Lycée Émilie du Châtelet is a state senior high school in Serris, Seine-et-Marne, France, in the Paris metropolitan area. The asteroid 12059 discovered by E.W. Elst was named after du Châtelet. In 2006, the Emilie du Châtelet Institute (IEC) was founded. In 2023, the Émilie Du Châtelet Society was founded in Paris. Three plays and an opera have been written about her.

There are some excellent overview articles available:

- The Directory of Women Philosopher’s page at the Center for the History of Women Philosophers and Scientists, which boasts an extensive list of secondary literature and an excellent overview over her primary works: https://historyofwomenphilosophers.org/project/directory-of-women-philosophers/du-chatelet-emilie-1706-1749/

- Karen Detlefsen and Andrew Janiak's Stanford Encyclopedia Article on Du Châtelet, which provides an excellent overview over the core tenets of her work: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/emilie-du-chatelet/

- Project Vox’s page on Du Châtelet, which features teaching materials and syllabi on Du Châtelet: https://projectvox.org/du-chatelet-1706-1749/

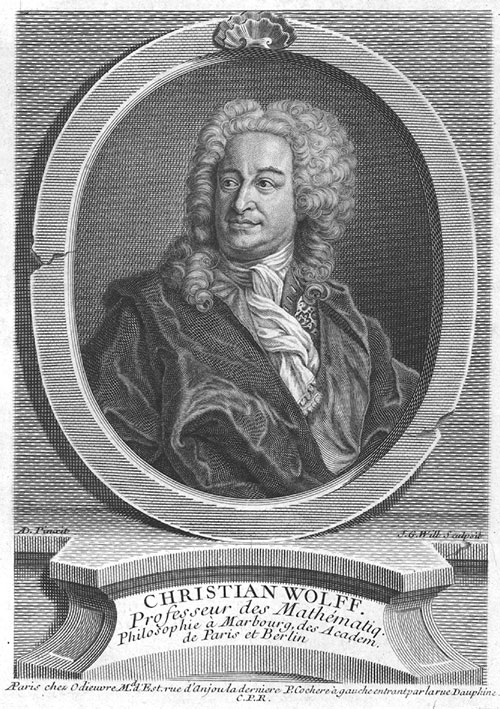

Contemporaneous Network(s):

Despite having received an excellent education, Du Châtelet suffered greatly from the exclusion of her sex from academic and scientific matters, as she expresses in the preface of her translation of Mandeville’s Fable of the Bees. Du Châtelet never indulged in self-pity and fought her way through a patriarchal society. On one occasion, for example, she was “politely” asked to leave the Café Gradot, a popular venue for intellectual and academic debates. She had male clothing made for her and returned, this time without being asked to leave. Many contemporaries and successors of Du Châtelet either doubted that she, as a woman, could be the author of her works or argued that her works are ‘male,’ Immanuel Kant, for example, wrote about her: “a woman who conducts learned controversies on mechanics like the Marquise de Chatelier might as well have a beard.” Until well into the 1980s her works have largely been read as a mere ‘adoption’, ‘repetition’ or ‘misunderstanding’ of Leibniz or Wolff’s works (cp. Garber 1968, Gardiner Janik 1982, Iltis 1977). The title of her book, Institutions Physiques, the dedication in the book–which was made to her son–and the note explaining that she presents Leibniz and Wolff’s ideas may be seen in a different light when considered in the context of the genesis of her work. We may not be able to answer the question about whether Du Châtelet would or could have accomplished the publication of her work in her name without the dedication to her son or with a less ambiguous and more ambitious title, however we must at least ask the question. Similarly, given the oppressive circumstances for women writing in natural philosophy at the time we simply do not know whether Du Châtelet was in a position to present her metaphysical theory as her own or whether a lack of attribution to Leibniz and Wolff would have resulted in detrimental circumstances for Du Châtelet or her work. Most importantly, little note has been given to the fact that society has been very hostile towards the idea that a woman could put forward any original ideas in metaphysics or philosophy. Du Châtelet skilfully navigated the balancing act between creating a space for herself within a male dominated scientific community and being true to herself as a female author.

Du Châtelet was a strong advocate for womens’ education and argued that the exclusion of women from colleges was to the detriment not only of women but of society and the sciences at large. Du Châtelet’s work has been translated by Louise Gottsched (1713-1762), a popular German female writer. Madame de Graffigny, a French playwright, novelist, and solonière wrote about Du Châtelet, “Our sex ought to erect altars to her!”

less

Significance

Émilie Du Châtelet was one of the most important figures of natural philosophy in the 18th century. Her main work, the Institutions de Physique, builds on Descartes, Leibniz and Wolff as well as on Locke and Newton. It deals with the principles of knowledge (principle of contradiction and principle of sufficient reason), God, the main concepts of metaphysical and physical truths (a being, essence, attribute, mode, substance), hypotheses, time and space, the elements of matter (simple beings), the nature of bodies, divisibility, motion, heaviness, attraction, and forces (dead and living forces). She is now being recognized, alongside Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and Christian Wolff, as one of the most accomplished Early Modern rationalists (Carus/McDonough 2024, Carus 2024, Hagengruber 2022) and as one of the most important post-Newtonian scientists in the history of physics and natural philosophy (Brading 2019, Janiak 2021).

Du Châtelet was the first and only French translator of Newton’s Principia, which she published along with two lengthy commentaries documenting her critical study of Newton’s main work and his ideas on the foundations of the science of physics. Du Châtelet also translated Mandeville’s Fable of the Bees along with a partly corrective introduction. The introduction, as well as her translation itself, reveals a highly appreciative yet critical reading of Mandeville’s original.

Du Châtelet wrote an extensive and widely circulated bible critique, which was published anonymously to avoid persecution and censorship by the church. She advocates for a rational belief in God and a critical reading of biblical scripture, which she describes as written by “interpreters.” She especially condemns biblical passages which portray God as cruel, unjust, or irrational. Her bible critique is one of the most important pieces of Clandestine literature (Seguin 2022). Du Châtelet was an excellent geometrician and mathematician. Furthermore, she wrote many poems and was greatly interested in theatre and opera. After losing a large amount of money gambling, she also invented an intricate financing arrangement similar to modern derivatives, which allowed her to pay back her debts.

Work:

Translation of Mandeville’s Fable of the Bees

In 1735, Du Châtelet embarked on a translation of Bernard Mandeville’s Fable of the Bees into French. This work was not published until after her death. As was common at the time, Du Châtelet altered the original text significantly during the translation and changed aspects of the text she did not approve of. As a result, the translation is an important source for deciphering Du Châtelet’s own views on the subject matter. The translation features an introduction and commentary by Du Châtelet, in which she reveals her own position on education and society.

Dissertation sur la nature et la propagation du feu (1738/1744)

In 1737, Voltaire and Du Châtelet independently entered papers on The Nature of Fire and its Propagation in an essay competition announced by the Académie Royale des Sciences. Neither won the competition but her contribution was the first ever paper written by a woman to be published by the Académie. Voltaire and Du Châtelet first collaborated on the project, but Du Châtelet did not agree with Voltaire on various issues, which led to the split. Maaike Korpershoek is currently investigating the points of departure between Voltaire and Du Châtelet. In 1744, Du Châtelet published a new edition of the essay, in which she references Leibniz more strongly.

Lettre sur les Eléments de la Philosophie de Newton (1738)

In 1738, Du Châtelet published this short piece which can be described as a book review of Voltaire’s work with the same title.

Institutions Physiques/ Institutions de Physique (1740/1742)

In 1738, Du Châtelet completed a first manuscript of her main work, which was first published anonymously under the title Institutions de Physique in Paris in 1740. In 1742, Du Châtelet published an augmented and longer version of the book under the title Institutions physiques de madame la marquise Du Chastellet adressés à M. son fiils. Nouvelle édition, corrigée et augmentee considérablement par l’auteur in Amsterdam. In the later edition Du Châtelet changes the French verb endings to the feminine form and thus emphasises her female authorship in comparison to the first edition. As early as 1743 her work was translated into German by Adolf Steinwehr and into Italian by M. de Mairan. The influence of her work on her contemporaries and successors is well documented. Many of her main concepts can be found verbatim, yet without mention of her name, in Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encyclopedia, which is a main scientific lexica of the 18th century. In 2009, Judith Zinsser and Isabelle Bour published a partial English translation of her 1740 work, and Katherine Brading offers a work-in progress translation of the remaining passages and chapters on her website. Unfortunately, there is still no complete and unified English translation of her main work, above all not of the 1742 augmented and corrected edition, in which Du Châtelet added several additional paragraphs. In 2010, Ángeles Macarrón prepared a partial Spanish translation.

The Institutions Physiques is a major work of natural philosophy. It draws on Leibniz, Wolff, Descartes, and Newton and examines the divide between philosophy and science, between metaphysics and physics. While the metaphysical aspects of the book long stood in the shadow of Leibniz and Wolff and, until the 1980s, were read as a mere “repetition” or “amalgamation” of Leibniz and Wolff, recent scholarship is recognizing the original contributions of her work, which were developed by Du Châtelet out of her in-depth reading of her predecessors and contemporaries (Cp. Amijee forthcoming, Brading 2019, Carus/McDonough 2024, Carus 2024a, Carus 2024b, Hagengruber 2012, 2022, Rey 2019). Similarly, in physics, Du Châtelet has long been seen as a mere apostle of Newtonian physics. While Newton was indeed the strongest influence on Du Châtelet in this respect, Katherine Brading (2019), Andrew Janiak (2023), and Marius Stan (2023) point out the originality of Du Châtelet’s physical theory in comparison to Newton.

De la Liberté

This short essay of the late 1730s, which was originally attributed to Voltaire, explores the concept of freedom and was originally intended to be included in the Institutions Physiques.

Correspondence with M. de Mairan (1741)

Du Châtelet engaged in a scientific public letter exchange with Jean-Jacques Dortous de Mairan on living forces. In 1741, the famous German writer Louise van Gottsched (maiden name Kulmus), translated the epistolary exchange into German, and in 1743, it was translated into Italian. The aim of Mairan’s 1728 dissertation was to settle the dispute on living forces. Du Châtelet put forward several objections to it in her Institutions Physiques, and she addresses those objections directly to Mairan in a 1741 letter. Voltaire, in turn, published a letter on living forces in 1741, taking Mairan’s side. As Du Châtelet may well have intended,, the dispute with Mairan turned out to be advantageous for her, as this helped to legitimise her thought in intellectual circles. Immanuel Kant references Du Châtelet’s theory of living forces in his early work, Thoughts on the True Estimation of Living Forces, of 1749.

Examens de la Bible (1742)

Du Châtelet wrote an extensive critique of both the Old and the New Testament. The work is best understood in the context of other Early Modern rationalists, like Leibniz, who held that theology must be free of contradiction and in line with rational principles. On the other hand, it must be seen in the context of clandestine literature, since Du Châtelet opposes accounts that violate natural law, i.e. miracles, as well as descriptions of God, which attribute immoral, unjust, and tyrannic actions to the Divine. The work was circulated anonymously to avoid censorship and persecution. Susana Seguin and Natalia Lorena Zorrilla Sirlin are currently working on a large project on clandestine literature with a particular focus on Du Châtelet.

Translation of Newton’s Principia (1749)

Émilie Du Châtelet’s translation of Newton’s Principia Mathematica was the first and is still the only French translation of this influential book. Completed shortly before her death, it was published ten years later. The book features an extensive commentary on Newton’s work, which boasts many of Du Châtelet’s own ideas.

Discourse sur le bonheur (1746)

This Discourse most likely dates back to 1746 but was not published until after Du Châtelet’s death. The central theme of the Discourse is on how to live a happy life. The piece is written from her personal perspective as a woman of her time. There are English, German, Italian, Spanish and Hungarian translations of the work.

Other writings:

In addition to the works above, Du Châtelet wrote an essay on optics and a piece entitled “Grammaire raisonnée,” both of which are published in Ira Owen Wade’s Studies on Voltaire, along with some unpublished papers by Mme Du Châtelet.

Reputation

Although Du Châtelet “felt the full weight of prejudice that excludes [women] so universally from the sciences,” (preface to the Fable of the Bees) she was also well established and highly regarded in the academic circles of her time. She was a member of the French Académie des Sciences and corresponded with many high ranking politicians, mathematicians, philosophers, scientists, and writers, among them Frederik the Great, Francesco Algarotti, Alexis Clairaut, Jean-Jacques d'Ortous Mairan, Pierre Louis Maupertuis, Leonhard Euler, members of the Bernouille family, and Christian Wolff.

Legacy and Influence

Du Châtelet had a strong influence on later Enlightenment authors. Johann August Eberhard, for example, quotes her text in his argument with Immanuel Kant (Hagengruber 2022). Many of her concepts and definitions, among them her idea of the principle of sufficient reason, found their way into Diderot’s and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie. Her works were read in France, Germany, Italy, and beyond. Today, she is recognized as one of the most important early modern rationalists, alongside Descartes, Leibniz, and Wolff.

less

Controversies

In 1741, Du Châtelet invited Samuel König to come to Cirey in order to receive lessons in geometry from him. Soon after, Du Châtelet realised she knew everything König was meant to teach her. She expressed this frustration in letters. Instead of learning geometry, she had König bring excerpts of Christian Wolff’s works and discussed these with him instead. König later left Cirey because of a dispute with Du Châtelet about his payments. König then accused Du Châtelet of plagiarising and misrepresenting his works in her Institutions Physiques. Du Châtelet defended herself vigorously. Today, König’s accusations have been proven to be unfounded.

less

Bibliography

Primary:

Inst1742: Du Châtelet, Émilie (1742), Institutions physiques de madame la marquise Du Chastellet adressés à M. son fils: Nouvelle édition, corrigée et augmentée considérablement par l'auteur. Amsterdam: Aux dépens de la Compagnie.

Inst1740eB: Du Châtelet, Émilie (1740/2017), Foundations of Physics, translated by K. Brading, a.a., available at www.kbrading.org.

Inst1740eZ: Du Châtelet, Émilie (1740/2009), Foundations of Physics. In Selected Philosophical and Scientific Writings, translated by I. Bour and J. Zinsser, edited by J. Zinsser, Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press, 115-200.

Du Châtelet, E. Examen de la Genèse. manuscripts non autographés, Bibliothèque de Troyes: no 2376.

Du Châtelet, E. Examen des livres du Nouveau Testament. manuscripts non autographés, Bibliothèque de Troyes: no 2377.

Du Châtelet, E. (1741). Réponse de madame la marquise Du Chastellet à la Lettre que M. de Mairan, secrétaire perpétuel de l’Académie royale des Sciences, lui a écrite le 18 février 1741 sur la question des forces vives. Bruxelles: Foppens.

Du Châtelet, E. (1744). Dissertation sur la nature et la propagation du feu. Paris: Prault Fils.

Secondary Literature:

Brading, Katherine. 2019. Émilie Du Châtelet and the foundations of physical science. New York: Routledge.

Carus, Clara/McDonough, Jeffrey. forthcoming. Émilie Du Châtelet in Relation to Leibniz and Wolff. Similarities and Differences. Cham: Springer.

Carus, Clara. 2024. Émilie Du Châtelet’s Metaphysics in Light of her Concept of ‘a Being’, Journal of Modern Philosophy.

Carus, Clara. 2024. Émilie Du Châtelet’s Theory of Simple Beings, Journal for the History of Women Philosophers and Scientists (3).

Carus, Clara. 2022. “Du Châtelet’s Contribution to the Concept of Time. History of Philosophy Between Leibniz and Kant.” In Époche Émilienne, ed. by Ruth Hagengruber. Cham: Springer. 113-128.

Detlefsen, Karen and Janiak, Andrew. 2017. Émilie Du Châtelet. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by E. N. Zalta, Winter 2017 Edition. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2017/entries/emilie-du-chatelet/

Hagengruber, Ruth. 2022. “Du Châtelet and Kant: Claiming the Renewal of Philosophy.” In Époche Émilienne, ed. by Ruth Hagengruber, Cham. 57-84.

Hagengruber, R. 2019. “Relocating Women in the History of Philosophy and Science. Emilie Du Châtelet (1706-1749), Laura Bassi (1711-1778), and Luise Gottsched (1713-1762) in Brucker’s Pinacotheca.” Bruniana & Campanelliana, Suppl XLIII (Studi 18).

Hagengruber, R. 2017. “If I Were King!” Morals and Physics in Emilie Du Châtelet’s Subtle Thoughts on Liberty. In J. Broad & K. Detlefsen (Eds.), Women and Liberty (pp. 195–205). Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

Janiak, Andrew. 2021. Émilie Du Châtelet’s Break from the French Newtonians. Revue d’Histoire des Sciences 74, 265–96.

Reichenberger, Andrea. 2016. Émilie du Châtelets Institutions physiques: über die Rolle von Prinzipien und Hypothesen in der Physik. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Seguin, Maria Susana. 2022. “Madame Du Châtelet, Clandestine Philosopher.” In Époche Émilienne, ed. by Ruth Hagengruber, Cham. 441-454.

Stan, Marius. 2018. “Emilie du Châtelet’s Metaphysics of Substance.” Journal of the History of Philosophy 56 (3): 477–496.

Wells, Aaron. 2023. Science and the Principle of Sufficient Reason: Du Châtelet Contra Wolff, Hopos, 24-53.

Wells, Aaron. 2021. Du Châtelet on Sufficient Reason and Empirical Explanation, The Southern Journal of Philosophy 59(4), 629–655.

Zinsser, Judith. 2007. Émilie Du Châtelet. Daring Genius of the Enlightenment. Penguin.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully