Birth

around 1365, Venice

Education

Christine was educated by her father. After her widowhood, she set out to build on what she knew through a period of self-education. She probably inherited some books and borrowed others from the libraries of her friends and acquaintances. She may have perfected her calligraphy skills under the tutelage of her husband.

Death

around 1430, France

Religion

CatholicChristine de Pizan was an Italian and French Medieval and Renaissance writer who is known for authoring some of the earliest pieces of feminist literature, including The Book of the City of Ladies, a feminist text recounting the capabilities and virtues of women.

Personal Information

Name

Christine de Pizan

Date and place of birth

around 1365, Venice

Date and place of death

around 1430, France

Family

Mother: Born in Venice to a bourgeois family from Forli in Romagna (Italy).

Father: Tommaso da Pizzano, born around 1318 in Bologna (the noble family originated from Pizzano, a small place in the vicinity of Bologna), died 1387 in Paris.

Marriage and Family Life

Born in Venice, Christine de Pizan spent the first years of her life in Bologna. She travelled at the age of four with her mother and brothers to Paris where her father had become a physician and astrologer at the court of Charles V. Her two brothers, Paulus and Aghinulfus, returned after the death of their father to take up their Bolognese inheritance. At the age of fifteen, Christine married Etienne de Castel (b. 1346, d.1390), a promising young royal secretary. Three children resulted from this marriage, but the names and destinies of only two are known. A daughter, her firstborn child, entered the Royal Priory of Poissy as a companion to Charles VI’s daughter, Marie, in September 1397. It is not known when she died. Her oldest son, Jean, born around 1385, would become a royal secretary like his father. He married Jehanne Coton in 1416. He was twelve in 1398, when he travelled to England to be a companion to the son of John Montagu, Earl of Salisbury. He was back to Paris in 1402 and may have been one of the copyists of his mother’s texts. Later he wrote a poem, Le Pin (1422-1424), which echoes them. Jean de Castel died in 1425. Nothing is known of the third child mentioned in the autobiographical narrative in L’Advision Cristine.

Education

Christine’s father taught her or had her taught the rudiments of Latin as well as how to read and write in the vernacular. In one place she describes the education she received as mere crumbs from the table of learning. Nevertheless, even as a child, she was spending enough time at her lessons for her mother to complain that it was keeping her from engaging in household tasks. Once she had emerged from financial troubles caused by her husband’s death, she began to write poetry and turned to a solitary life of study. She regretted that during the lives of her father and husband she had been too preoccupied with household duties and with bearing and caring for her children to have paid proper attention to the knowledge they might have transmitted to her. From this period, she began to acquaint herself with all the ancient history and philosophical poetry that was accessible to her. Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy, Dante’s Divine Comedy, Ovid’s Metamorphosis, as well as the history of Troy and the ancient history up to Julius Caesar were important early influences.

Religion: Catholic

A French narrative of the Passion of Our Savior made at the request of the queen of France in 1398, the Passion de Jhesu nostre sauveur, known as Passion Isabeau, is sometimes attributed to Christine. Her texts of piety were among the most appreciated in the 15th century (Oroyson Nostre Seigneur, illustrated by a Man of Sorrows). The layout of the first manuscripts of her Epistre Othea are based on the model of a glossed Bible, and the religious meaning this text gives to mythological stories reveal a temptation to be a word of authority in the field, but Christine never crossed the line and kept away from the religious controversies of her time. When she had to flee from Paris in 1418 under threat from the Burgundians, she retired in an abbey somewhere in France, possibly as a nun.

Transformation

In her allegorical, rhymed, universal history, Le Livre de la mutacion de Fortune Christine describes herself as being transformed from a woman into a man after the death of her husband. Having been widowed, she found herself in a parlous economic position, with debts owed by her husband for property that had reverted to the crown. She had great difficulty gaining access to money owed to her, and at one point she found herself involved in cases in four different courts. This experience made her bitterly aware of the misfortune of being a woman and of the difficulties facing widows. Yet she overcame her tribulations, initially finding her voice as a courtly poet. After being commissioned to write a history of Charles V she turned to writing in prose and produced a series of important political and early feminist works.

Familiarity with Aristotle transformed her understanding of the causes of women’s parlous social status. She came to recognise the deleterious influence of opinion and set out to oppose the misogynous claims of philosophers and poets from Aristotle to Jean de Meun and Matheoleus. In The Book of the City of Ladies she no longer represents herself as transformed into a man but proposes that the women who accept male lies concerning their nature are like the fool who believed that he had been transformed into a woman, having been dressed in women’s clothes while asleep.

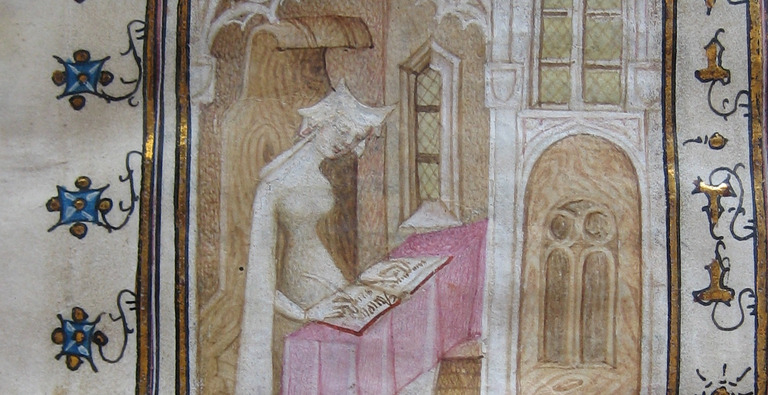

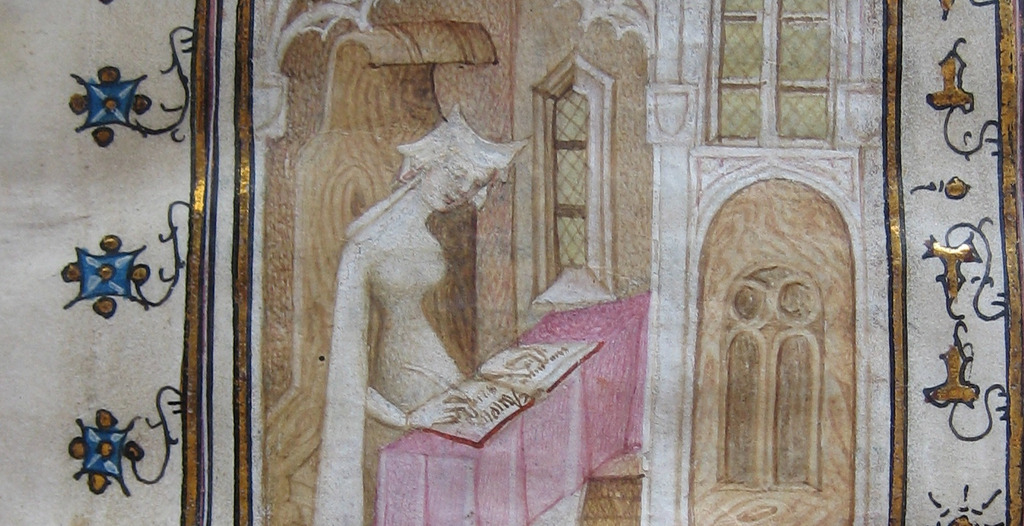

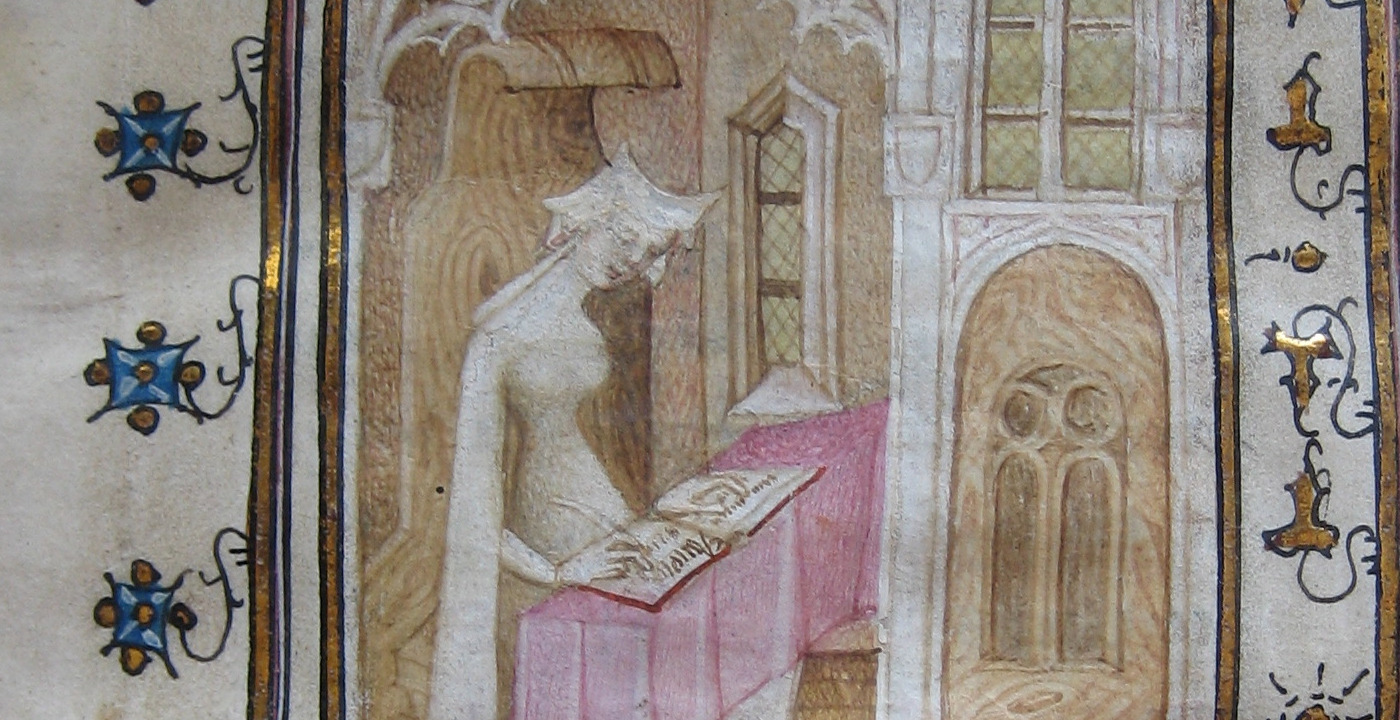

She became her own scribe, editor, and producer of manuscripts, which encompassed all the contemporary genres.

Contemporaneous Network(s)

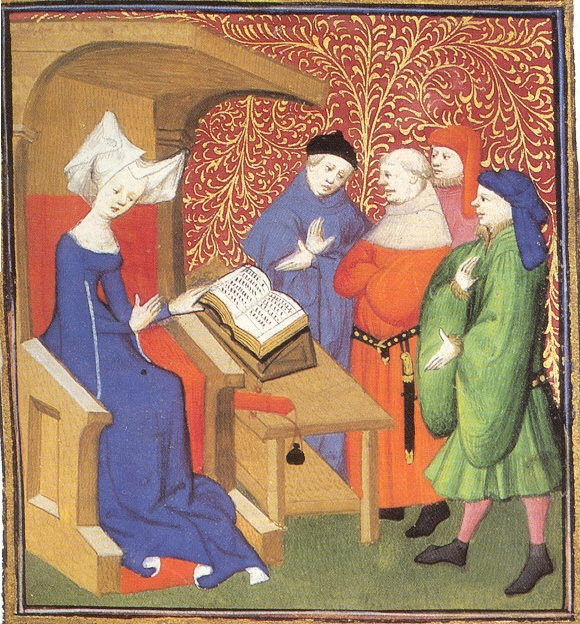

Although her poetic self-image casts her as lamenting in solitude the loss of her husband, Christine’s patrons, friends, and acquaintances included many members of the extended royal court, clerics, intellectuals, and particularly women. Valentina Visconti, wife of Charles VI’s brother, Louis of Orleans, was an early patron, and the queen Isabella of Bavaria (later known by the vocalized form of the name, Isabeau) also paid her for various works ultimately commissioning the luxury collection, Harley 4431, now in the British Library.

Christine calls Anne of Bourbon/Montpensier a friend whom she loved. Anne, the daughter of Catharine de la Marche, duchess of Castres, had been Mary of Berry’s sister-in-law and after being widowed as a result of the disaster of Nicopolis, she married Isabeau of Bavaria’s brother, Louis. Another patron, Charles d’Albret, was also related to Isabeau, suggesting Christine’s close connection with members of the nobility associated with Isabeau’s court. In her dedicatory epistle to the Livre du debat sur le Rommant de la Rose (1402), she calls herself chambermaid to queen Isabeau, which implies official functions rewarding her advice. The distribution to princes and lords of her Epistre à la reine (1405), which supports the political role of the queen, shows Christine acting as a propagandist of Isabella’s peace policy.

less

Significance

Works/Agency

The diversity, quantity, and quality of Christine’s oeuvre is outstanding, not simply for her time but for an intellectual of any time. She was not merely an author, but also the scribe, designer, and publisher of many of the early manuscripts of her works. She was a courtly poet, debating the nature of love and the dangers to both men and women of foolish love, seduction, and disappointment in works such as Cent Ballades, Le Livre du debat de deux amans, Le Livre des trois jugemens, Le Dit de Poissy, Le Dit de la pastoure, and Le Livre du duc des vrais amans. She was a critic of men’s treatment of women and of their misogynistic literary representations, and a defender of women’s moral and intellectual equality with men, who argued in Le Dit de la rose, L’Epistre du dieu d’amours, Le Debat sur le Roman de la Rose, L’Advision Cristine, and Le Livre de la cité des dames that men and women are different bodily forms of one species, equally endowed with immaterial souls, who should be as equally valued and benefitted as men. She produced hybrid works combining mythological, historical, allegorical, and political elements such as L’Epistre Othea, Le Livre du chemin de longue estude, Le Livre de la mutacion de Fortune, as well as more conventional works of history and political advice in Le Livre des fais et bonnes meurs du sage roi Charles V, Le Livre du corps de policie, Le Livre de paix, and Le Livre des trois vertus, unusual in being a mirror for princesses and other women. She compiled a practical manual of warfare, Le Livre de fais d’armes et de chevalerie, bringing to non-Latinate knights the classical knowledge of Vegetius and Frontinus, and intervened in the political events and crises of the conflict between the Burgundians and Armagnacs in L’Epistre à la reine and Lamentacion. She wrote works of spiritual consolation, Sept Psaulmes allegorisés, Oroison Nostre Dame, Epistre de la prison de la vie humane, and Heures de contemplacion sur la Passion de Nostre Seigneur Jhesucrist, while her last work, celebrating the achievements of Joan of Arc, is one of the earliest and most important sources of the prophetic mission that Joan had appeared to fulfill.

For reasons of economy but above all to ensure the correction of copies of her texts in the absence of copyright and to keep control of their distribution, Christine launched her own private copying workshop. It involved a mastery of book production, writing styles, and rules of page layout at a time before the invention of the printing press. The fifty extant original manuscripts produced under her supervision, more than any other medieval writer, testify to its effectiveness. These manuscripts were not sold but ‘given’ on special occasions, mainly for New Years Eve, in expectation of reciprocal reward. The copies intended for princes were illustrated with miniatures painted by the best illuminators in Paris, some named after her works (Othea Master, Master of the City of Ladies and the newly baptized “Maître de la Pastoure”). Among the border decorators she employed was an “enlumineresse,” Anastaise, praised in the Cité des dames. The author portrait often placed at the opening of her books highlights Christine as an authority figure. It imprints on people’s minds to this day the moral image of the solitary “lady in blue” in her study. The traditional scene of handing over the book to a patron served as a reminder of the gift and called for reward and consideration in return. In the Harley manuscript, a vivid view of the queen’s ceremonial chamber is thus emphasized as a site of female, regal authority. Christine also gave instructions for cycles of images: the Epistre Othea, conceived as an illustrated text, was enhanced by a hundred miniatures, which are part of the work. She renewed compositions (the wheel of Fortune, the unclassical Perseus mounted on Pegasus, Death as a deity, the “sons” of the Planets) that were influential over centuries, revealing her as a brilliant iconographer.

At least one of her ballads, Dueil engoisseus, was set to music by a contemporary, the Flemish composer Gilles Binchois (b. ca. 1400, d. 1460).

Contemporaneous Identifications

As one of the first readers in France of Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio, but also as a correspondent for academics such as Jean de Montreuil, Jean Gerson and the Col brothers, Christine de Pizan is part of the milieu of French pre-humanism. Guillebert de Mets, in his nearly contemporary description of Paris (1434), mentions her as having written treatises in Latin and French.

Reputation

The high status of her patrons—who included the dukes of Orleans, Burgundy, and Berry—and value of the gifts that she received in recognition of the manuscripts that she presented to them, attest to Christine’s excellent reputation as a producer of luxury books during her lifetime. After her death, she did not completely disappear from view and was memorialised by Martin le Franc in 1441 as equal to Cicero in eloquence and to Cato in wisdom. In many instances, her works lived on without her authorship being acknowledged. Between 1488 and 1549 various printed editions of Fais d’armes et de chevalerie appeared in French and in English translation, but the preface was removed in order to make the author pass for a man. The Epistre Othea was similarly printed in both languages. The Livre des trois vertus was printed in French and Portuguese, the Cité des dames and Corps de policie appeared in English in 1521, a Dutch translation of Cité des dames was printed, and in 1549 a prose version of the Chemin de long estude de Dame Christine de Pise appeared. In 1478, the English translation of her Proverbes moraux was one of the earliest works printed by Caxton. Between 1549 and 1786 she came to the attention of various bibliophiles, but it was only in 1786 that Louise de Keralio-Robert republished a biography, due to Boivin, and in the second and third volumes of her Collection des meilleurs ouvrages françois: composés par des femmes, dédiée aux femmes françoises edited sections of a large proportion of Christine’s works, many of which had previously only existed in manuscript. So it appears that Christine ‘of Pisa’ was never completely forgotten. She was known to 19th century historians for her history of Charles V and testimony on Joan of Arc and appreciated in the beginning of the 20th for her verses after Roy’s edition of her poetry. Since then, despite the disparaging and misogynistic judgement from Gustave Lanson, who in his Histoire de la littérature française of 1920 calls Christine an “unbearable bluestocking,” her reputation and influence have grown. Simone de Beauvoir mentioned her, though somewhat dismissively, in The Second Sex. Now, due to the hard work of many female and a few male scholars, modern editions and English translations of most of her works have become available; the most famous today being the City of Ladies. Nevertheless, the widespread recognition she deserves for the important place that she occupied in the history of European political thought has not yet been attained.

Legacy and Influence

The Livre des fais d’armes et de chevalerie is one of the earliest European texts on the laws of war, to the point that Christine de Pizan has been presented as the “mother of international law.”

Christine entered contemporary popular culture in 1979 after being given a place at Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party.

The international Christine de Pizan Society has held important conferences dedicated to the discussion of her life and works since 1992.

Honoré Champion published a collection, Etudes Christiniennes.

Her works, particularly those relevant to the status of women, are now taught in many university courses.

less

Controversies

Controversy

One of Christine’s earliest works involved her in a controversy over the literary merit and moral acceptability of Jean de Meun’s Romance of the Rose, which Christine criticised for its lewdness and debased representation of women, and compared unfavourably, as a poetic production, to Dante’s Commedia. More recently there has been controversy over whether she ought to be thought of as a feminist. Those who understand feminism to be an offshoot of democratic liberalism have assumed that her monarchism and acceptance of social hierarchy disqualify her as a feminist. Others, who see feminism more broadly as opposition to the masculinist doctrine that women should be subject to men because they are men’s natural inferiors, claim that her promotion of queenship and defence of women’s capacity and right to rule led her to refute the arguments for women’s moral and rational inferiority and to argue for their equal possession of natural prudence, marking her out as a cogent late Medieval feminist thinker. Strange enough for a French speaking writer and supposed “première femme de lettres française,” Christine seems more similar to Anglo-Saxon activists than to French feminists, but her popularity is growing with a larger audience.

New and Unfolding Information and/or Interpretations

Recent detailed manuscript studies have identified many autograph manuscripts produced in her atelier and shown her role in the program of illumination found in them.

New evidence from archival sources has illuminated her family origins.

Work continues on her milieu, sources, relationship to the Italian humanist tradition, and on her last poem praising Joan of Arc, as evidence for the nature of Joan’s mission.

less

Clusters & Search Terms

Current Identification(s)

History, political philosophy, feminism, art history, poetry, literary theory, paleography

The richness of Christine’s work now justifies a new field of research at the crossroads of literary studies, codicology, political philosophy, gender and art history, the so-called “études christiniennes.”

Clusters

Many dedicatees of Christine’s works were knights and male rulers (seneschal Jean de Werchin, constable Charles d’Albret, the dauphin Louis of Guyenne, Duke Jean of Berry, etc.), especially for her manual of warfare. She seems to have had a direct influence on orders of chivalry founded for the defense of women and of widows threatened with spoliation and verbal abuse (in 1399: the Green Shield or Ordre de la dame blanche à l’écu vert by marshal Boucicaut and Charles d’Albret; in 1401: the Cour amoureuse of King Charles VI, founded by the Dukes of Bourbon and Burgundy, of which Jean de Castel was a member), including her own Order of the Rose in 1402, whether fictitious or not. But her educational role with this male readership does not seem to have withstood the upheavals of the end of the 15th century, and by the beginning of the 16th her Dit de la rose bothered a male reader at the English Court, most probably Henry VIII himself.

Later, European queens, princesses, and duchesses, from Isabelle of Portugal, wife of Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, Anne of France, daughter of Louis XI, Marguerite of Burgundy, Louise of Savoy and her daughter Marguerite of Navarre, to Elizabeth I of England, variously disseminated or knew some of Christine’s works, owned “City of Ladies” tapestries, and represented themselves as prudent monarchs, in line with the representations of noble queenship that she had developed.

As late as the 17th century, there is evidence of Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle having access to the Queen’s manuscript, while in the 18th century, female descendants of the Cavendish/Harley line, which possessed this manuscript, were prominent as friends and patrons of intellectual women, including Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Elizabeth Montagu and Elizabeth Elstob.

Louise Keralio-Robert was the first to seriously analyse and edit selections from her works.

Search Terms

Charles V of France, Charles VI of France, Charles VII of France, Isabeau of Bavaria, Louis of Guyenne, dauphin of France, Louis of Orleans, Cabochien revolt, Burgundian/Armagnac conflict, Joan of Arc, Romance of the Rose, courtly love, defense of women.

References in existing schemas

Blanche of Castille was one of the queens regent praised by Christine in her Cité des dames. The 1521 English translation of the Cité des dames appeared during Catharine of Aragon’s campaign for her daughter’s right to rule.

less

Bibliography

Primary (selected):

Pizan, Christine de. 1886. Oeuvres Poétiques de Christine de Pisan. Edited by Maurice Roy. 3 vols. Paris: Librairie de Firmin Didot et Cie. Reprint, Johnson Reprints,1965.

---. 1959. Le Livre de la mutacion de Fortune. Edited by Suzanne Solente. 4 vols. Paris: Éditions A & J Picard.

---. 1977. Le Ditié de Jehanne d'Arc. Translated by Angus J. Kennedy and Kenneth Varty. Edited by Angus J Kennedy and Kenneth Varty. Oxford: Medium Aevum Monographs.

---. 1983. The Book of the City of Ladies. Translated by Earl Jeffrey Richards. London: Picador. 1405.

---. 1984. Christine de Pizan's epistre de la vie humaine. Edited by Angus J. Kennedy.

---. 1984. The Epistle of the Prison of Human Life with An Epistle to the Queen of France and Lament on the Evils of the Civil War. Translated by Josette Wiseman. London and New York: Garland Library of Medieval Literature.

---. 1985. The Treasure of the City of Ladies. Translated by Sarah Lawson. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

---. 1998. The Love Debate Poems of Christine de Pizan. Edited by Barbara K. Altmann. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

---. 1989. Le Livre des trois vertus. Edited by Charity Cannon Willard and Eric Hicks. Paris: Champion.

---. 1990. Christine de Pizan's Letter of Othea to Hector. Translated by Jane Chance. Newburyport MA.: Focus Information Group.

---. 1991. The Book of the Duke of True Lovers. Translated by Thelma S. Fenster. New York: Persea.

---. 1993. Christine's Vision. Translated by Glenda K. McLeod. New York: Garland.

---. 1994. The Book of the Body Politic. Translated by Kate Forhan. Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

---. 1995. Le Livre du duc des vrais amans. Edited by Thelma S. Fenster. Binghamton N.Y.: Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies.

---. 1997. La Città delle dame. Translated by Patrizia Caraffi. Edited by Earl Jeffrey Richards. Milano & Trento: Luni Editrice.

---. 1997. Le Livre des faits et bonnes moeurs du roi Charles V le Sage. Translated by Eric Hicks and Thérèse Moreau. Paris: Stock.

---. 1998. Le Livre du corps de policie. Edited by Angus J. Kennedy. Paris: Honoré Champion.

---. 1999. The Book of Deeds of Arms and of Chivalry. Translated by Sumner Willard. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

---. 1999. The Book of the City of Ladies. Translated by Rosalind Brown-Grant. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

---. 1999. Epistre Othea. Edited by Gabriella Parussa. Geneva: Librarie Droz.

---. 2000. Le Chemin de longue étude. Edited by Andrea Tarnowski. Paris: Livre de Poche.

---. 2001. Le Livre de l'advision Cristine. Edited by Liliane Dulac and Christine Reno. Paris: Champion.

---. 2008. The Book of Peace. Translated by Karen Green, Constant J. Mews and Janice Pinder. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

---. 2015. Le livre du duc des vrais amants. Edited by Dominique Demartini et Didier Lechat. Paris: Champion.

---. 2014. The Boke of the Cyte of Ladyes. Translated by Brian Anslay. Edited by Hope Johnson. Tempe, Arizona: ACMRS.

---. 2015. CD Christine De Pizan - Chansons et Ballades by VocaMe. Berlin Classics : Edel.

---. 2017. Heures de contemplacion sur la Passion de Nostre Seigneur Jhesucrist. Translated by Liliane Dulac and René Stuip. Edited by Liliane Dulac and René Stuip. Paris: Champion.

---. 2017. Les Sept psaumes allegorisés. Edited by Bernard Ribémont and Christine Reno. Paris: Champion.

---. 2017. Othea's Letter to Hector. Translated by Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski and Earl Jeffrey Richards. Toronto, Ontario: Iter Press.

---. 2021. Le Livre des fais d’armes et de chevalerie. Edited by Lucien Dugaz. Paris: Garnier.

---. 2021. The Book of the Body Politic. Translated by Angus J. Kennedy. Toronto, Ontario: Iter Press.

---. 2021. The God of Love’s Letter and The Tale of the Rose, with Jean Gerson, A Poem on Man and Woman. Translated by Thelma S. Fenster and Christine Reno. Toronto, Ontario: Iter Press.

Secondary (selected):

Adams, Tracy. 2014. Christine de Pizan and the Fight for France. University Paris: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Altmann, Barbara K., and Deborah McGrady, eds. 2003. Christine de Pizan: A Casebook. New York and London: Routledge.

Autrand, Françoise. 2009. Christine de Pizan, une femme en politique. Paris: Fayard.

Bell, Susan Groag. 2004. The Lost Tapestries of the City of Ladies: Christine de Pizan's Renaissance Legacy. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Blumenfeld-Kosinski, Renate, ed. 1998. The Selected Writings of Christine de Pizan. New York: W. W. Norton & Co.

Brown-Grant, Rosalind. 1999. Christine de Pizan and the Moral Defence of Women. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Buschinger, Danielle, Liliane Dulac, Claire Le Ninan and Christine Reno eds. 2012. Christine de Pizan et son époque. Actes du Colloque international des 9, 10 et 11 décembre 2011 à Amiens. Amiens: Presses du Centre d'études médiévales, Université de Picardie - Jules Verne.

Campbell, John, and Nadia Margolis, eds. 2000. Christine de Pizan 2000: Studies of Christine de Pizan in Honour of Angus J. Kennedy. Amsterdam and Atlanta: Rodopi.

Caraffi, Patrizia, ed. 2013. Christine de Pizan, la scrittrice e la città / L'écrivaine et la ville / The Woman Writer and the City. Atti del 7. Convegno internazionale Christine de Pizan, Bologna, 22-26 settembre 2009. Florence: Alinea.

Demartini, Dominique, and Claire Le Ninan, eds. 2021. Genèses et filiations dans l’œuvre de Christine de Pizan. Paris: Classiques Garnier.

Desmond, Marilynn, ed. 1998. Christine de Pizan and the Categories of Difference. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Dor, Juliette, Marie-Élisabeth Henneau and Bernard Ribémont, eds. 2008. Christine de Pizan, une femme de science, une femme de lettres. Paris: Champion.

Dulac, Liliane, and Bernard Ribémont, eds. 1995. Une Femme de lettres au Moyen Age: Études autour de Christine de Pizan. Orléans: Paradigme.

Dulac, Liliane, Anne Paupert, Christine Reno and Bernard Ribémont, eds. 2008. Désireuse de plus avant enquerre. Actes du VIe Colloque international sur Christine de Pizan, Paris, 20-24 juillet 2006. Volume en hommage à James Laidlaw. Paris: Champion.

Forhan, Kate. 2002. The Political Theory of Christine de Pizan. Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate.

Green, Karen. 2021. Joan of Arc and Christine de Pizan’e Ditie. New York: Lexington.

Green, Karen, and Constant J. Mews, eds. 2005. Healing the Body Politic: the political thought of Christine de Pizan. Turnhout: Brepols.

Hicks, Eric, Diego Gonzalez and Philippe Simon, eds. 2000. Au Champ des escritures. IIIe Colloque international sur Christine de Pizan, Lausanne, 18-22 juillet 1998. Paris: Champion.

Hindman, Sandra. 1986. Christine de Pizan's "Épistre Othea" Painting and Politics at the Court of Charles VI. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies.

Kennedy, Angus J., Rosalind Brown-Grant, James C. Laidlaw, and Catherine M. Müller, eds. 2002. Contexts and Continuities. Proceedings of the IVth International Colloquium on Christine de Pizan (Glasgow 21-27 July 2000) Published in Honour of Liliane Dulac. Glasgow: University of Glasgow Press.

Margolis, Nadia. 2011. An Introduction to Christine de Pizan. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Ouy, Gilbert, Christine Reno, and Inès Villela-Petit. 2012. Album Christine de Pizan. Turnhout: Brepols.

Parussa, Gabriella, and Andrea Valentini eds. 2021. Studi Francesi, vol. 195 : Christine de Pizan en 2021: Traditions, filiations, genèse et diffusion des textes.

Ribémont, Bernard, ed. 1998. Sur le chemin de longue étude. Paris: Honoré Champion.

Richards, Earl Jeffrey and Joan Williamson, eds. 1992. Reinterpreting Christine de Pizan. Athens, Georgia: The University of Georgia Press.

Villela-Petit, Inès. 2020. L’atelier de Christine de Pizan. Paris: BnF Éditions.

Willard, Charity Cannon. 1984. Christine de Pizan: her life and works. New York: Persea.

Archival Resources (selected):

Archives Nationales de France

Archivo di Stato di Bologna

Web Resources (selected):

Comment

Your message was sent successfully