Feared by the powerful, loved by the poor, and misunderstood by many, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela stands as one of South Africa's most complex and uncompromising figures. Branded both a freedom fighter and a rebel, she embodied liberation's fierce, often painful contradictions. While Nelson Mandela became the symbol of reconciliation, Winnie became the face of resistance: unyielding, defiant, and unwilling to forgive a system that had brutalized her people. Her life was not one of quiet diplomacy but of fire and struggle. She confronted apartheid with a courage that terrified its architects and defied the patriarchal structures that sought to silence her. To speak of Winnie Mandela is to describe the heartbeat of Black South African womanhood; bold, wounded, and unrelenting in its pursuit of justice.

Personal Information

Name: Nomzamo (meaning she who strives) Winifred (Winnie) Madikizela

Birth: September 26, 1936, in Bizana, Pondoland District, Transkei (now Eastern Cape), South Africa

Death: April 2, 2018, in Johannesburg, South Africa

Education: Winnie Madikizela Mandela earned a degree in social work from the Jan Hofmeyr School of Social Work in 1956 and later earned a bachelor's degree in International Relations from the University of Witwatersrand.

Religion: Methodist

Family

Mother: Gertrude Mzaidume Madikizela, the first domestic science teacher in Bizana.

Father: Columbus (no other name provided), a schoolteacher.

Siblings: Nonyaniso Khumalo, Mobantu Mniki, and Msuthu Madikizela

Grandfather: Chief Mazingi, a business owner who ran a functioning farm.

Paternal grandmother: Seyina

Husband: Nelson Mandela

Children: Zindziswa Mandela, Zenani Mandela

Childhood and Family Life

Winnie descended from a line of powerful women. Her paternal grandmother, Seyina, inherited her husband's vast land holdings after his death. She also ran the trading post and leased land to white settlers. Winnie's Mother, apart from being the first domestic science teacher in Bizana, was charming and particular about her appearance, a trait that Winnie inherited. She was a disciplinarian and strictly adhered to her Methodist values. Winnie called her mother "a religious fanatic" and attributed her teenage rebellion against the church to her mother’s religious discipline. Her Mother passed away when she was nine years old.

Her father, Columbus, was a schoolteacher and a headteacher. Together with his siblings, they embraced the various changes going through their part of the world while also maintaining a solid connection to local traditions and customs. Columbus’s relationship with Christianity was ambivalent. This distrust of settler society, culture, and religion meant Winnie grew up in a space always open to questioning oppression. Her father was her first teacher; he taught her history from textbooks and history that was not featured in books. Winnie stated, "I became aware at an early age that the whites felt superior to us. And I could see how shabby my father looked compared to the white teachers. That hurts your pride when you are a child; you tell yourself: If they failed in those nine Xhosa wars, I am one of them, and I will start from where those Xhosas left off and get my land back."

Members of the Madikizela extended family were Xhosa-speaking people of the Pondo nation situated in what is today the so-called homeland nation of the Transkei. Her parents were mission-educated, English-speaking teachers who centered their children's education.

Education

Winnie moved to Johannesburg, where she attended the Jan Hofmeyr School of Social Work. Her career in social work eventually led to her involvement in activism. Winnie finished her social work studies in 1955. She earned a bachelor's degree in International Relations from the University of Witwatersrand. Later, she received a scholarship to study in the United States. However, she ultimately decided to stay in South Africa to continue her career as a social worker at Baragwanath Hospital. She was the first Black person to hold such a position. Winnie ultimately became engaged in political activism and research about social justice issues. She used her social work skills and knowledge to examine township infant mortality rates. Working at Baragwanath Hospital, she connected with hundreds of patients whose experiences highlighted how horrible the effects of poverty, caused by racist policies, were on the quality of life of those in her community.

Marriage

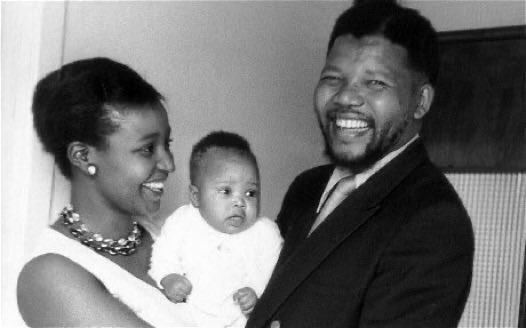

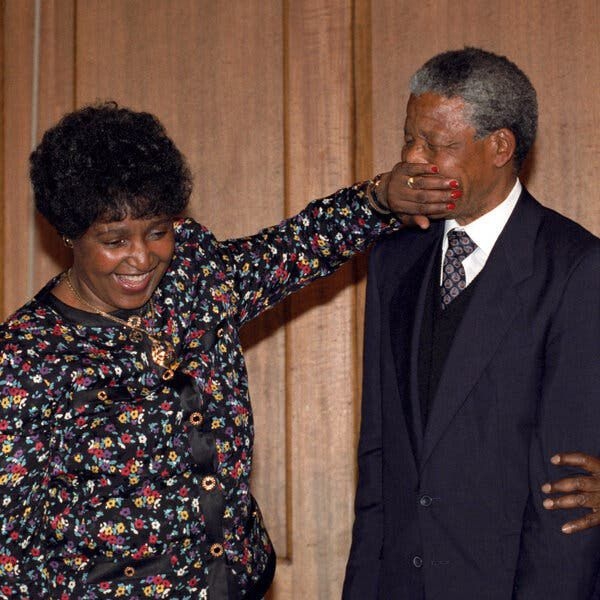

Winnie met Nelson, who was 16 years her senior, for the first time in the Johannesburg Regional Court, where he represented a colleague whom police had assaulted. He was a patron at The School of Social Work. Her father could not understand how Winnie had become involved with one of the most influential people in the country at the time. They married in June 1958 in her home, Pondoland, while Nelson was involved in a Treason trial. After moving to Soweto, Winnie continued her activism while Nelson continued his political involvement with the African National Congress (ANC). Due to their similar work against Apartheid, their home became a frequent meeting point for apartheid work, making it a hot spot for police raids. Nelson returned to Johannesburg before finishing the traditional marriage ceremony, where they were also supposed to get married in his home. According to the family elders, this meant they never finished the traditional marriage process.

They had two daughters, Zindziswa and Zenani Mandela, who were heavily impacted by their parents' anti-apartheid activities. Winnie Mandela never knew when police would tear her away from her terrified children and jail her on some triviality. She finally made the painful decision to send her children to boarding school in Swaziland so that they could live and learn without getting harassed by the South African Government.

The marriage between Winnie and Nelson was a tragic love story. They only spent five years of their 38 years of marriage together before Nelson was imprisoned for 27 years. During this time, Winnie worked tirelessly, dedicating her life to the liberation struggle and fight against Apartheid in South Africa while Mandela was in prison. They divorced in 1996 after failing to salvage the marriage after Nelson was released.

less

Legacy and Influence

A tribute to Nomzamo Winnie Mandela by Bishop Manas Buthelezi, President of the South African Council of Churches and Bishop in the Lutheran Church of South Africa. In this tribute, the bishop says, "In a profound sense, she qualifies for the title of the Mother of Black People. I am not saying this simply because she happens to be the wife of her husband, one of the imprisoned leaders of black people, but also because of what she has become of her right."

Mother of a Nation (Anti-Apartheid activist)

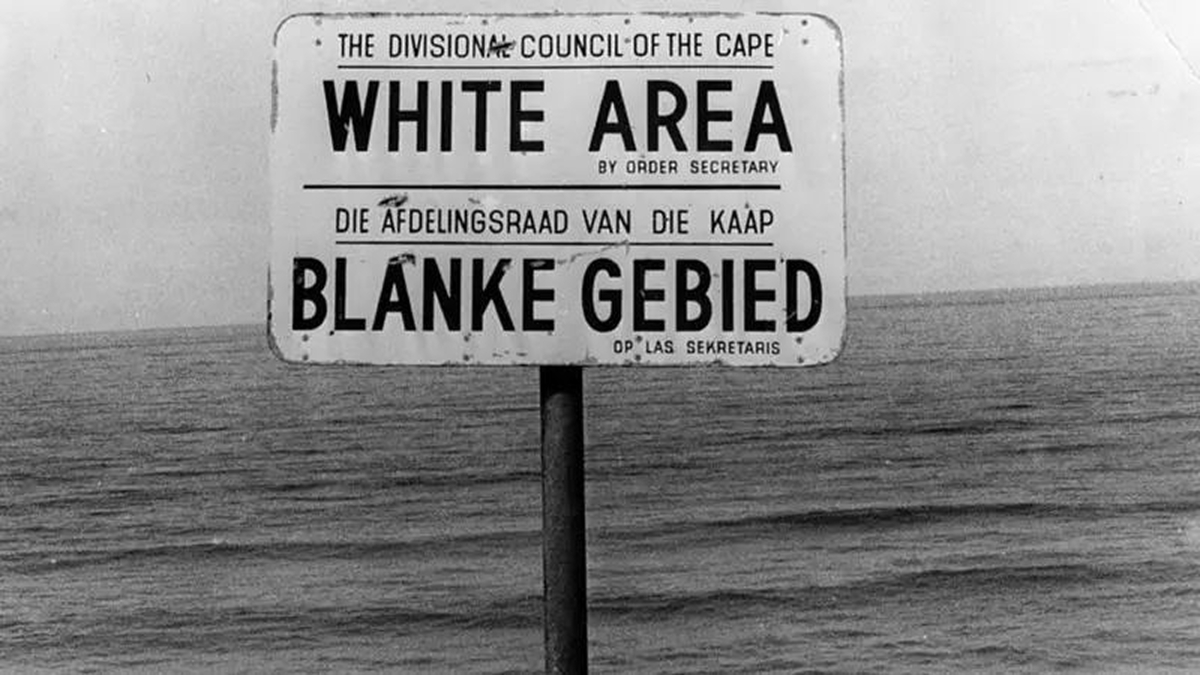

Winnie Mandela was known as the "Mother of a Nation," due to being one of the most vital female voices against the apartheid system in South Africa. Apartheid in South Africa spanned from 1948 to 1994 and was a system of all-white governance that enforced racial segregation. It required that non-white South Africans, most of the population, live in separate areas from white people and use different public facilities. Contact between the two racial groups was limited. The white and black racial groups were physically separated according to location, public facilities, and social life.

A post depicting apartheid laws that privileged white people and separated South Africans along racial lines.

Her first experience with the racial discrimination that came with Apartheid was in 1945, when she was just nine years old. News had just arrived that World War II had just ended; accompanied by her siblings and her father, they went to the city hall for celebrations, only to find that it was a "white only" affair, and they were not allowed to enter the city hall. They were all forced to remain outside as the celebrations went on.

As her activism continued, so did the raids, arrests, and detentions by Apartheid police throughout the 60s and 70s. Between 1958 and 1960, Winnie gave birth to two children, and at the same time, Nelson was in and out of prison. Due to her involvement as an anti-apartheid leader, when Nelson started his 27-year incarceration, Winnie was constantly targeted by the police, who even went so far as to have her children expelled from school due to her activism.

She described "that midnight knock when all about you is quiet during this time. It means those blinding torches shone simultaneously through every window of your house before the door was kicked open. It means the exclusive right the security branch has to read every letter in the place. It means paging through every book on your shelves, lifting carpets, looking under beds, lifting sleeping children from mattresses, and looking under the sheets. It means tasting your sugar, mealie meal, and every spice on your kitchen shelf, unpacking all your clothing, and going through each pocket. Ultimately, it means your seizure at dawn, dragged away from little children screaming and clinging to your skirt, imploring the white man pulling Mummy away to leave her alone. Went further to her children being expelled from school due to her activism.

White Man's Fear

This phrase often references Winnie Mandela’s powerful and defiant presence within the anti-apartheid struggle. It captures how she came to embody everything that the apartheid regime and, more broadly, white supremacy feared most: a Black woman who refused to be silent, submissive, or broken. Her life, politics, and even her image challenged the very foundations of the racial and patriarchal order that apartheid depended on. During apartheid, the South African state was built on the belief that white rule was natural, permanent, and justified. To maintain that illusion, the regime relied on keeping Black South Africans oppressed, politically, economically, and psychologically. For this system to function, it needed to crush rebellion and control symbols of resistance. Winnie Mandela shattered that control. She refused to conform to the expectations of docility placed upon Black women and emerged as a fearless leader who inspired the masses to resist.

When Winnie was banished to Brandfort, she realized how differently white and black people lived in South Africa. She started going into shops that black people never went into. Whenever she went into the supermarket, the Afrikaans women would leave until she was finished shopping. To the other black people watching from outside, they thought it was out of respect. Once she started going to white spaces, her fellow black people began doing the same. She had been banished to a white-populated area where most residents had never heard of ANC or Nelson Mandela, or the struggle black South Africans went through outside their dystopia. To them, Winnie was a communist. In her own words, she said, "I am a symbol of whatever is happening in the country. I am a living symbol of the white man's fear. I never realized this fear's deeply embeddedness until I came to Brandfort."

During her banishment from 1977 to 1984, Winnie transformed her forced isolation into a source of empowerment for the residents. Despite being under constant surveillance, she established essential services that significantly impacted the lives of those around her. She set up a crèche (preschool), providing childcare support to working parents, and a soup kitchen in her own home, ensuring that many went hungry no longer. She also established a mobile clinic, bringing much-needed medical care to the community. Beyond these initiatives, Winnie’s connection with the residents of Brandfort was palpable. She regularly provided food and blankets to impoverished families, often going beyond material support to offer emotional comfort and solidarity.

Her commitment to education was evident in her efforts to aid residents. Many recall her paying for their books and school transport, demonstrating her dedication to empowering the younger generation. Her support extended to women and youth as well. She organized a sewing club, providing skills and economic opportunities, and played a pivotal role in establishing a local high school, recognizing the transformative power of education.

Moreover, she established a juvenile center for troubled youth, offering them a haven and guidance to navigate the challenges of their circumstances. While often overshadowed by her national political role, these actions speak to the depth of her commitment to community development and social welfare. Through her work in Brandfort, Winnie embodied the spirit of resilience and community empowerment, leaving an indelible mark on the town and its people.

The recollections of locals paint a nuanced picture of Winnie, one that complements her radical efforts against apartheid with the personal connections she forged with residents. Her legacy in Brandfort is a testament to the impact one individual can have on a community. The multifaceted nature of her contributions continues to inspire and motivate generations. Brandfort was officially renamed Winnie Mandela Town in 2021, paying tribute to the anti-apartheid stalwart who lived there during her banishment from 1977 to 1984.

Gender, Power, and Defiance

Winnie Madikizela-Mandela also challenged the patriarchal structures within both apartheid and the liberation movement itself. Her fearlessness unsettled white men in power, and many of her male comrades were unaccustomed to women asserting themselves politically. By taking up leadership roles, addressing crowds, and refusing to be confined to the domestic sphere, she defied expectations of how a woman, especially a Black woman, should behave. Her confidence, eloquence, and militancy exposed how patriarchy was intertwined with colonial domination.

Her existence as a powerful, politically active Black woman was itself revolutionary. In this sense, “the white man’s fear” was not simply about her as an individual but about what she represented: the rise of a new, self-defined African womanhood, one that was assertive, proud, and politically conscious. Winnie Mandela’s political and personal life demonstrated that gender and race could not be separated in understanding the nature of oppression. Apartheid was not only a system of racial segregation; it was also built upon patriarchal control that sought to subjugate women as much as it did Black men. Winnie’s defiance, therefore, struck at the very core of both racial and gender hierarchies, exposing how deeply intertwined they were in sustaining oppression.

From the earliest years of her activism, Winnie refused to be treated as a secondary figure in the liberation movement. While many women were expected to play supportive roles while men led the political struggle, Winnie demanded visibility and voice. She took up public leadership at a time when men almost entirely dominated political spaces. Defiance of patriarchal expectations also forced the liberation movement to confront its contradictions. Even as the ANC fought against racial oppression, it often reproduced gender inequality within its ranks. Winnie’s leadership and militancy unsettled these norms. She made it impossible for male comrades to ignore women’s contributions or to claim moral superiority while women suffered imprisonment, torture, and banishment alongside them. Her insistence on women’s agency within the liberation movement laid the groundwork for future generations of South African women activists, who would later fight for gender equality in the democratic era.

Winnie Mandela’s defiance was so profound that it was not rooted in ideology alone—it was personal, embodied, and deeply human. She had lived through harassment, exile, solitary confinement, and the constant threat of death. Yet she refused to retreat into bitterness or fear. Her life became a testament to endurance as a political weapon. Even when stripped of freedom and dignity, she refused to surrender her identity as an African woman or her belief in justice. Her body, voice, and very existence became sites of resistance.

Campaign Against HIV and AIDS

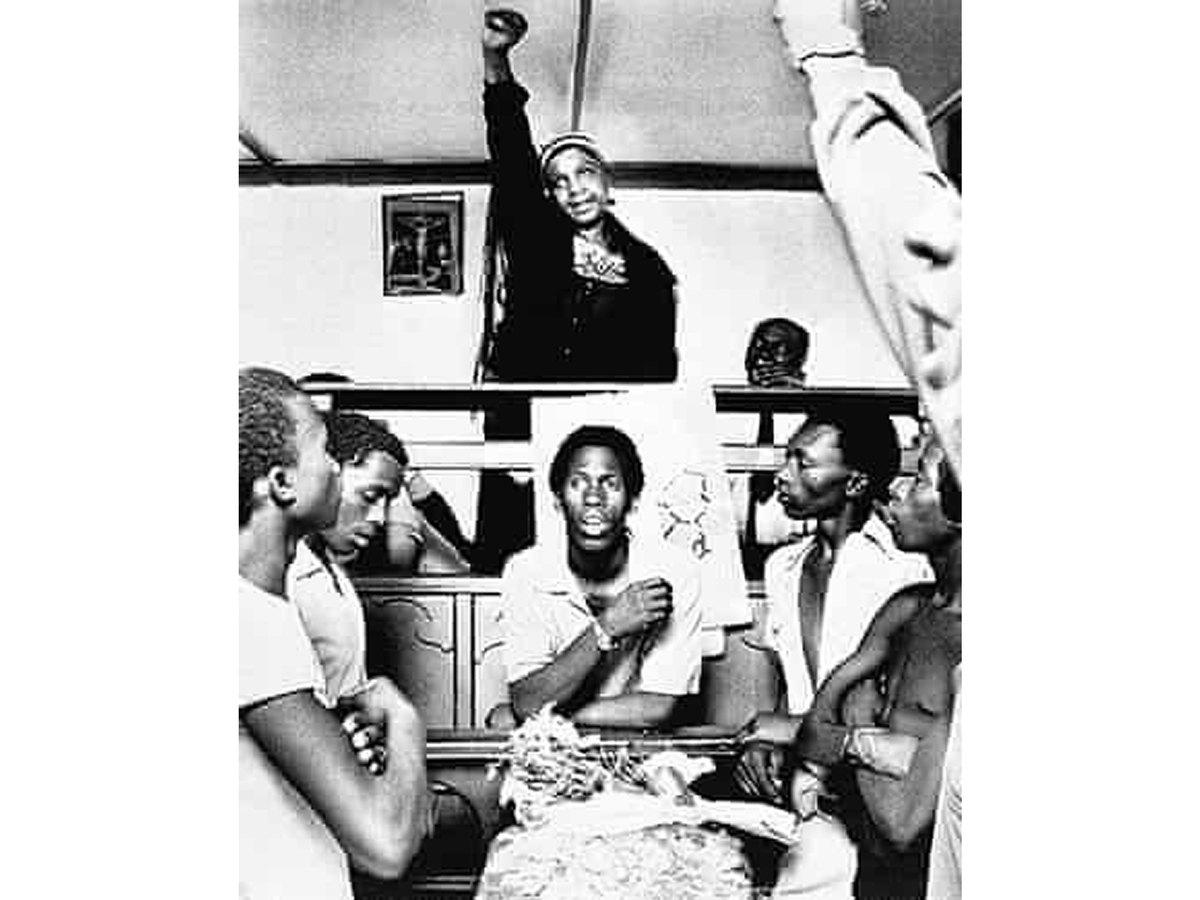

During the 1990s and early 2000s, South Africa faced one of the world’s most severe HIV/AIDS epidemics. The disease spread rapidly in communities already ravaged by poverty, inequality, and the lingering effects of apartheid. At the same time, silence and denial were widespread in society and at the highest levels of government. Drawing on her background as a trained social worker, Winnie understood the deep social dimensions of the epidemic. She argued that the AIDS crisis could not be addressed merely as a medical issue but had to be seen as part of a broader struggle for human rights, dignity, and equality. She spoke forcefully about how women, especially those in poor and rural communities, were disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS because of systemic gender inequality and economic vulnerability. Her activism emphasized the intersection between patriarchy, poverty, and disease, making her one of the first major South African politicians to link women’s rights directly to the fight against AIDS.

When she was the head of the African National Congress Women's League, she gave a dynamic address, saying that they were marching to demand that the elected Government put the interests of its people before the profits of the drug companies. At the Durban World AIDS Day Conference on Tuesday, July 11, 2000, the people marched and demanded access to HIV/AIDS medication from Thabo Mbeki's Government. The march was led by Winnie Mandela, religious leaders, labor union officers, doctors, and AIDS activists.

Earlier in the day, Winnie Mandela spoke at a rally before the march, calling for lower drug prices. After rousing the crowd with anti-apartheid chants and songs, Winnie Mandela said, "If we could struggle against AIDS with the same commitment as we did against apartheid, we could turn the tide." She blasted drug companies for profiteering and railed against the South African Government for not breaking pharmaceutical patents. AIDS, she said, "is a social holocaust. We cannot declare this the African Century and continue to ignore this pandemic, as some African leaders have been doing."

Although her political career was often marked by controversy, Winnie’s AIDS activism is integral to her legacy. In confronting both stigma and denial, she helped create space for public dialogue and greater understanding at a time when silence was deadly. She demonstrated the same fearlessness that had defined her anti-apartheid resistance this time, in the face of a different but equally devastating struggle. Through her work, she reminded South Africans that the fight for freedom did not end with the fall of apartheid; it continued in the ongoing battle against poverty, inequality, and disease.

Winnie’s contribution to AIDS activism was rooted in empathy and defiance. She saw the humanity of those society sought to marginalize and refused to remain silent while others suffered. In doing so, she helped lay the groundwork for a more open, compassionate national response to HIV/AIDS and reaffirmed her lifelong commitment to justice for the oppressed.

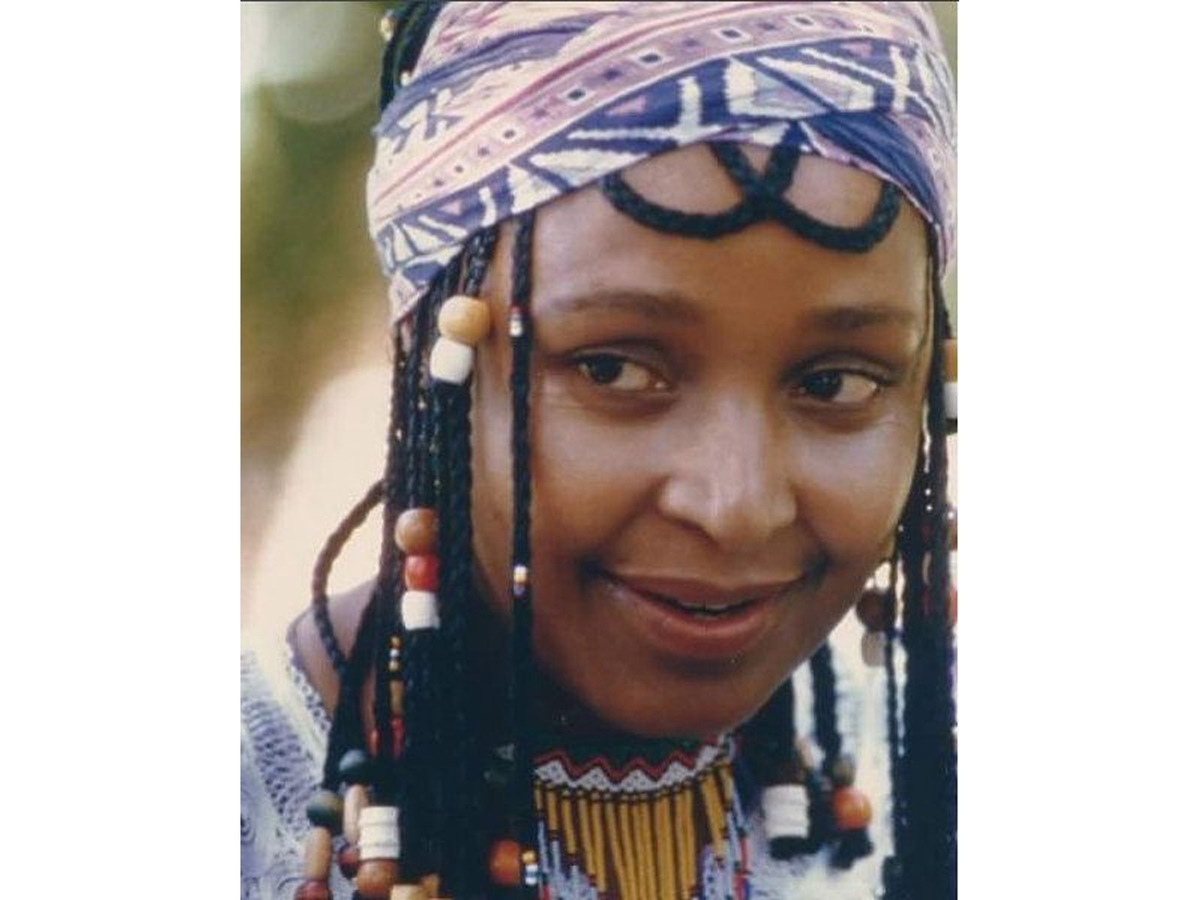

Fashion as Activism

Fashion has long been a powerful form of expression and resistance, particularly in African contexts where clothing has carried deep cultural, political, and symbolic meaning. Across the continent, activists, artists, and political figures have used dress not merely as decoration but as a language of defiance, identity, and solidarity. Winnie Mandela, whose distinctive style became an enduring symbol of resistance during and after apartheid. Her fashion use was not superficial; it was deliberate, political, and profoundly African, communicating strength, pride, and defiance in the face of oppression.

In Africa, fashion has often intersected with activism by celebrating indigenous identity and resistance to colonial norms. Under colonial rule, Western dress codes were used as tools of control and assimilation, promoting the idea that European styles represented civilization and authority. In response, many African leaders and activists reclaimed traditional and locally inspired forms of dress as statements of cultural pride and political resistance. Winnie Mandela’s fashion choices stood out within this broader tradition as deeply symbolic acts of political resistance and empowerment.

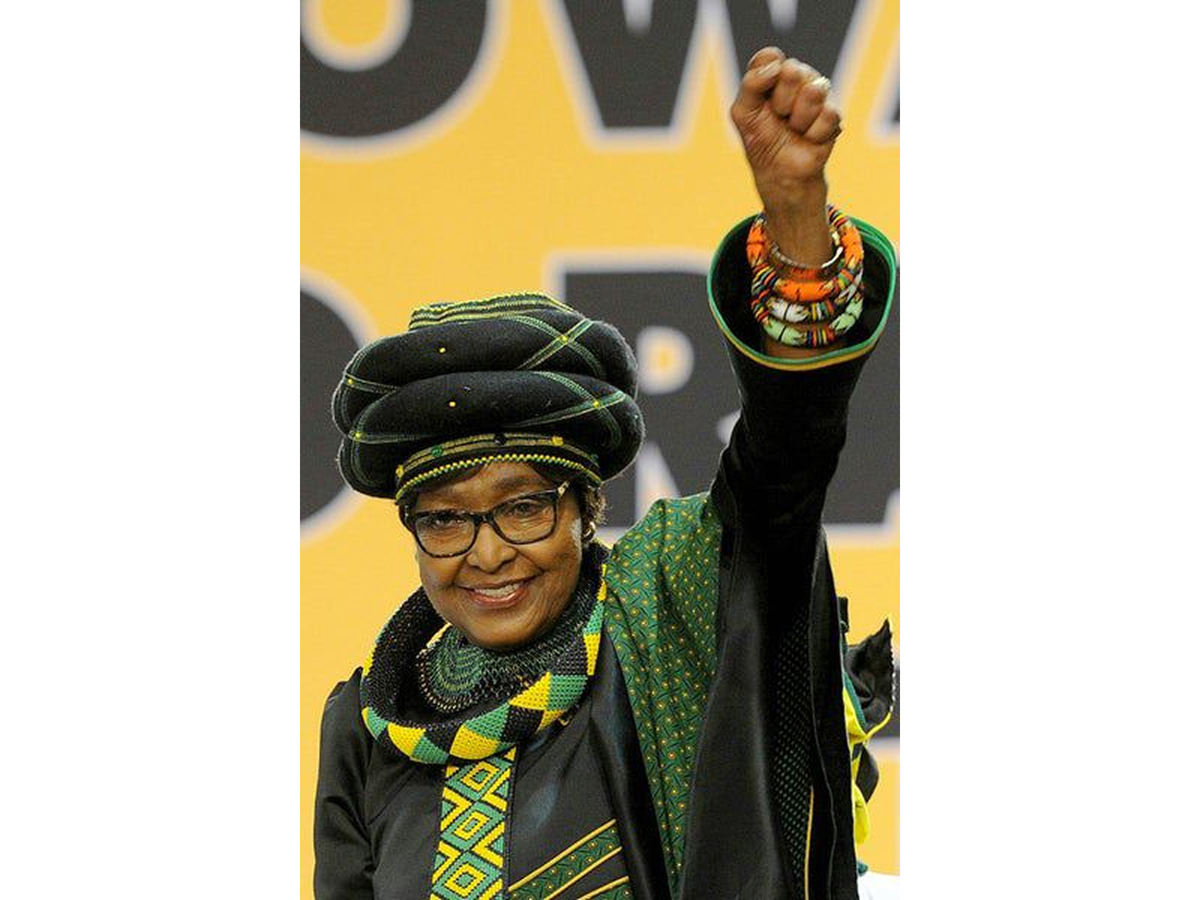

Winnie’s fashion was unapologetically African and resolutely political. During the long years of her husband Nelson Mandela’s imprisonment, Winnie became the public face of the anti-apartheid struggle, and her appearance was central to that image. She often wore traditional African attire, including the Xhosa-inspired doek (headscarf), beaded necklaces, and boldly patterned fabrics that reflected her Xhosa heritage. Winnie did not choose these garments merely for cultural pride; they were part of her activist identity. In a society that sought to devalue African culture and erase Black identity, her clothing became a visible rejection of white colonial beauty standards and Western authority. She embodied resistance, dignity, and self-determination when she appeared before the press or at political rallies in traditional dress.

Winnie Mandela, adorned in a headwrap with beads in her hair.

The headwrap became one of her most enduring symbols. In South African townships, it was a common accessory worn by working-class Black women. But when Winnie Mandela wore it publicly and consistently, it transformed into a political statement, a crown of resilience. The doek communicated solidarity with the struggles of ordinary Black women while asserting authority in spaces where Black women were often marginalized. It became a visual shorthand for defiance against apartheid and patriarchal control. Many women began to emulate her style, using fashion to align themselves with the liberation struggle and reclaim their identity with pride.

Beyond her personal style, Winnie Mandela’s influence also extended into broader movements where fashion became a collective tool of protest. During the 1980s and 1990s, young activists and women’s groups in South Africa began using clothing such as ANC colors (green, black, and gold), African prints, and militant uniforms as symbols of unity and political allegiance. Winnie’s iconic look was part of this larger culture of “visual activism,” where fashion was used to communicate resistance, belonging, and hope. In post-apartheid South Africa, her style continued to inspire designers and activists who use fashion to celebrate Black pride, gender equality, and social justice.

491 Days

On a cold winter’s morning, hours before dawn on May 12, 1969, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela was arrested in the presence of her two young daughters, Zenani and Zindziswa. At the time, she was under a banning order that confined her to her home in Orlando West, Soweto, between 6 a.m. and 6 p.m., and prohibited her from attending gatherings or leaving the area. The order had already isolated her from the political networks that sustained her, preventing her from visiting her husband, Nelson Mandela, in prison. Yet her resolve had not faltered, and her continued defiance made her a prime target of the apartheid state. That early morning arrest marked the beginning of 491 harrowing days of detention, during which she would endure physical and psychological torment intended to break her spirit, but which only strengthened her determination to fight.

Winnie was detained under the Terrorism Act No. 83 of 1967, one of the apartheid regime’s most oppressive pieces of legislation. This law permitted the state to arrest and detain individuals indefinitely without trial if they were suspected of endangering “the maintenance of law and order.” It was a weapon designed to crush political activism and silence dissent. Her arrest was part of a broader crackdown on anti-apartheid activists. In Winnie’s case, it was also deeply personal: she had become a symbol of defiance, a woman whose strength and visibility challenged both the racial and patriarchal order upon which the regime depended.

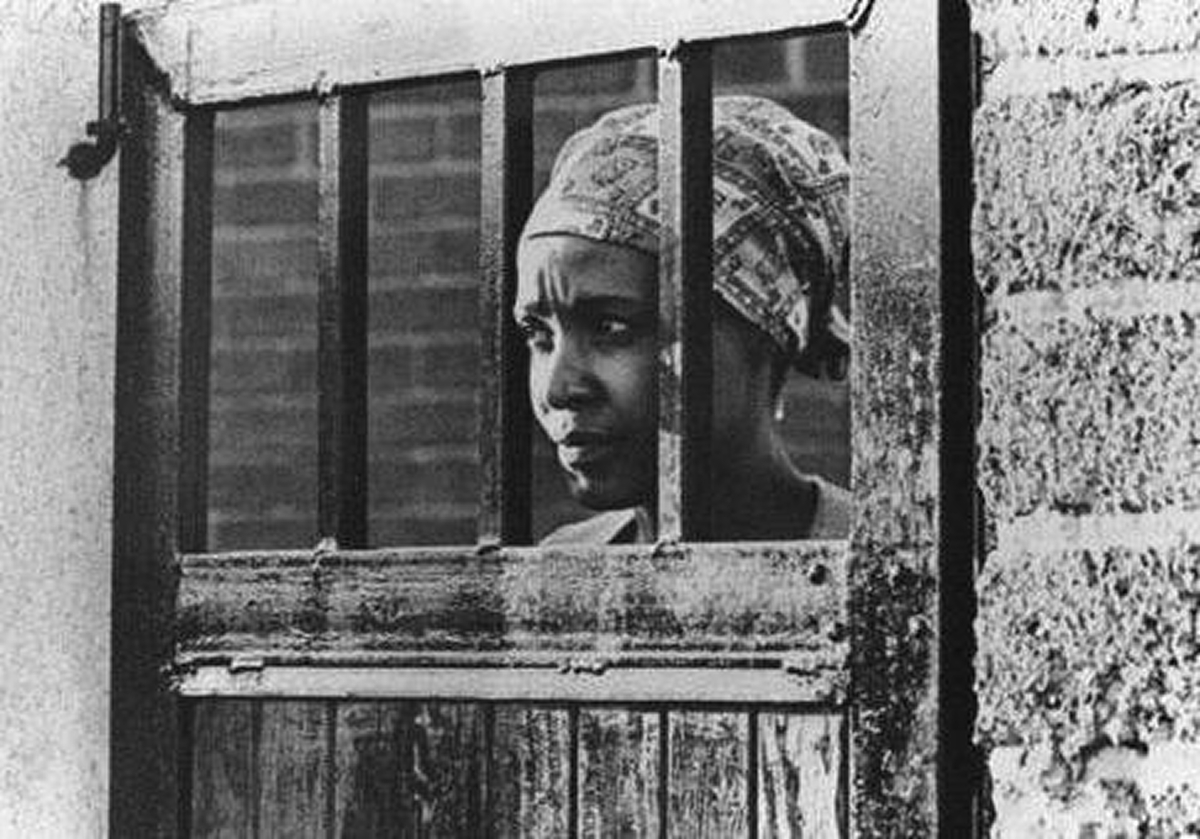

For the first 200 days of her imprisonment, Winnie was held in solitary confinement in Pretoria Central Prison. Solitary confinement was not merely physical isolation; it was psychological warfare. Prisoners were deprived of human contact, subjected to constant light or darkness, and interrogated for hours without rest. In her memoir, 491 Days: Prisoner Number 1323/69, Winnie recalls the unbearable silence, the cold that bit through her thin clothes, and how her mind struggled to cling to sanity. The authorities tried to extract confessions, to force her to betray comrades, and to make her denounce the African National Congress (ANC). She refused.

Her greatest pain came from the separation from her daughters. The apartheid regime weaponized motherhood, knowing that the thought of her children suffering without her would inflict unbearable emotional agony. Yet even in isolation, Winnie refused to give her captors the satisfaction of despair. She found strength in her faith, in fragments of song and prayer, and in the memory of her people’s suffering. She later wrote that she realized she was not alone; her pain was part of a collective struggle endured by millions of Black South Africans under apartheid. Surviving became, for her, an act of resistance.

Winnie Mandela was released after 491 days. She emerged physically frail but unbroken. The authorities expected to find a woman shattered by imprisonment and humiliation; instead, they found a leader whose defiance had only hardened. Her release transformed her into a symbol of endurance and courage, particularly for Black women who saw in her story their own resilience under oppression. Her experience exposed the cruelty of apartheid’s security system, but it also revealed the extraordinary strength of those who resisted it.

Winnie’s 491 days in detention ultimately reshaped her political identity. Before her arrest, she had been viewed primarily as Nelson Mandela’s wife and a supporter of the ANC. After her release, she was no longer seen as merely the partner of a prisoner; she had become a political force in her own right. Her ordeal made her a living symbol of South Africa’s struggle: unyielding, uncompromising, and unwilling to be silenced.

The experience left deep emotional scars but strengthened her conviction that liberation required sacrifice. The 491 Days became more than a measure of time; they represented the resilience of the human spirit against systemic cruelty. Through her suffering, Winnie Mandela gave the world a testimony of resistance. She transformed her pain into power, silence into speech, and imprisonment into a legacy that would outlast the walls that tried to contain her. Winnie’s time in prison was meant to break her. Instead, it made her immortal in South Africa’s liberation story.

A New Voice in the Struggle

During the mass arrest of women, the African National Congress (ANC), led by Nelson Mandela and Oliver Tambo, raised money to pay for the fines. At this moment, it became clear that Winnie was becoming a force to be reckoned with. National security realized she could be a political threat, independent of her already-known husband. In 1969, Winnie was involved with the ANC and was later arrested under the Suppression of Terrorism Act, where she spent an entire year in solitary confinement.

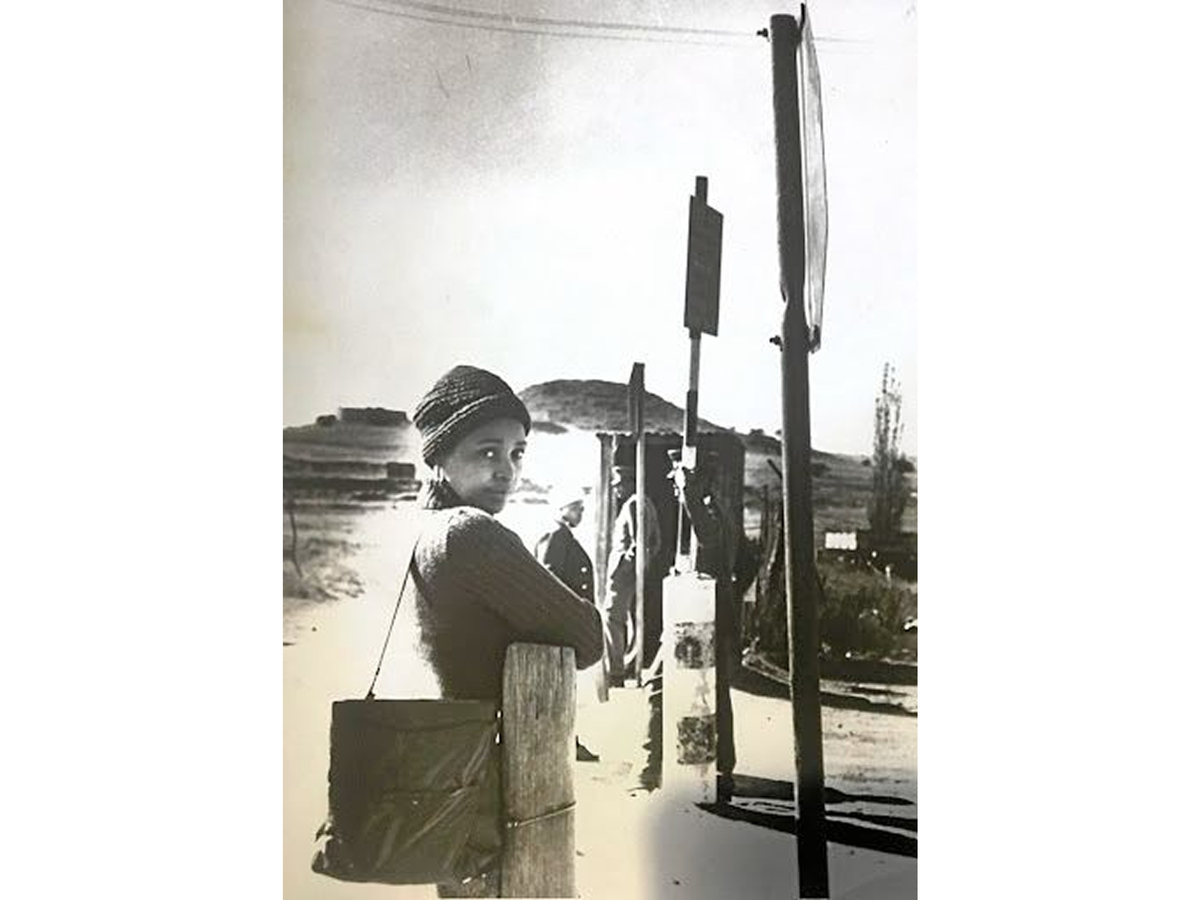

Banishment and the Soweto Uprisings

Winnie received banishment orders and was heavily restricted from living normally, working, and socializing. She was also prohibited from publishing or addressing more than one person at a time, subjected to house arrest, incarcerated in solitary confinement, and terrorized by police harassment and arbitrary detention. During the Soweto Uprising on Wednesday, June 16, 1976, 20,000 Soweto schoolchildren protested the government order that Afrikaans must be the language of instruction in black secondary schools.

The students marched in protest of the Bantu Education system and for the release of Nelson Mandela and other political prisoners. The police pinned incitement of violence on Winnie, and again, she was detained. The police held her in custody for five months, eventually releasing her in December 1976 without charge. The following year, on May 17, 1977, she was seized from her home in the Orlando section of Soweto and forced to reside in the black township outside the rural town of Brandfort in the distant Orange Free State, where she spent eight years of her life. People were told not to socialize with her as she was perceived as a dangerous terrorist.

Awards and Achievements

- 1985: Received the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Award for her tireless fight for justice and human rights during apartheid.

- 1988: Honored with the Candace Award for Distinguished Service by the National Coalition of 100 Black Women in the United States for her leadership and activism.

- Post-1994 (Democratic Era): The South African government awarded the Order of Luthuli in Silver for her outstanding contribution to the liberation struggle and her bravery in the face of apartheid persecution.

- 2018: Conferred with an Honorary Doctor of Laws (LLD) degree by Makerere University in Uganda, recognizing her lifelong commitment to the anti-apartheid movement.

- Legacy Honors (Posthumous):

The Mbizana Local Municipality in the Eastern Cape was renamed Winnie Madikizela-Mandela Local Municipality.

The town of Brandfort, where she was once banished, was renamed Winnie Mandela.

A major road in Ekurhuleni, Gauteng — the R562 connecting Midrand and Olifantsfontein — was renamed Winnie Madikizela-Mandela Road in her honor.

less

Controversy

Angry Black Woman

Her life was not without its ups and downs. Winnie's frequent arrests, banishment, and harsh interrogations affected her mental health and worldview. She became more militant in her work and determination to end Apartheid. Only through a white supremacist lens could criticism of "excessive military force," which was often lodged against her, be considered valid while Black people were at war against a savage oppressor who had forcefully claimed their homeland and dehumanized them. Winnie, for decades, was the victim of the violent state apparatus, which sought to punish those vocally seeking liberation for Black South Africans.

A fearless woman and a freedom fighter, Winnie fell victim multiple times to police harassment, multiple detainments, banishments, and even injury. Like many freedom fighters across Africa, the quest to liberate one’s people involved necessary violence to fight an oppressive system of racial injustice. In October 1958, Winnie participated in a mass action that mobilized women to protest against the Apartheid government's infamous pass laws.

The laws required Black South Africans over 16 to always carry a passbook, called a dompas. The dompas was like a passport, but it contained more pages filled with more extensive information than a standard passport. Within the pages of an individual's dompas were their fingerprints, photograph, personal details of employment, permission from the Government to be in a particular part of the country, qualifications to work or seek work in the area, and an employer's reports on worker performance and behavior. The mass action led to the arrest of Winnie while she was pregnant, her friend Albertina Sisulu, a prominent anti-apartheid leader, and 1000 other women. They spent two weeks in jail, refusing to post bail as a sign of further protest. In prison, they experienced horrible conditions, which pushed her further to fight for liberation.

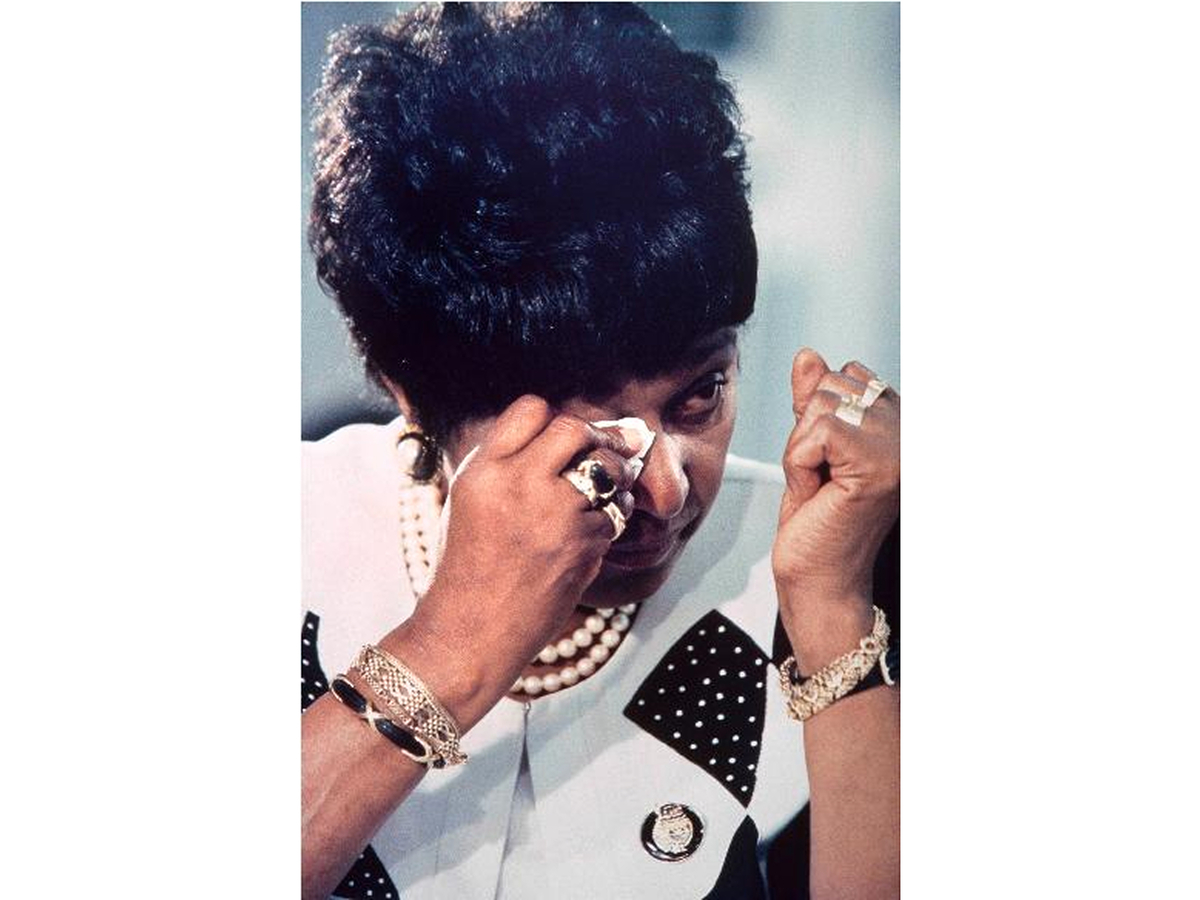

The Death of Stompi Moeketsi and the Famous Speech

In 1988, Winnie’s controversial Mandela United Football Club, a group of young men who lived in her newly built house in Soweto and acted as her bodyguards, caused many anti-apartheid groups to distance themselves from her. The police charged two club members with the kidnapping and beating of three African youths and the abduction and murder of 14-year-old Stompie Moeketsi. Moeketsi was a young leader whose 1500-member "children's army" opposed Mandela's club and its tactics.

Winnie’s bodyguards were suspected of two other murders and in South Africa's largest organizations. In 1989, the Congress of South African Trade Unions and the United Democratic Front issued statements disassociating themselves from Winnie and her entourage. She finally had the club dismantled after pressure from the ANC and her husband. Mandela's once unblemished image was tarnished in the eyes of her people, and it wasn't until Nelson Mandela's release from prison in 1990 that she was somewhat rehabilitated. In one of her famous speeches, Winnie endorsed the necklacing of apartheid collaborators "with our boxes of matches and our necklaces we shall liberate this country - the stoning, the bullets, the terrible deaths of "informers."

Anger Towards Nelson Mandela

In the years following South Africa’s transition to democracy, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela’s relationship with Nelson Mandela grew politically and personally strained. While the world celebrated Nelson Mandela as a symbol of peace, forgiveness, and reconciliation, Winnie remained fiercely critical of seeming compromises made during the negotiations that ended apartheid. Her anger toward Nelson was rooted in personal disappointment and a profound sense of political betrayal.

“Mandela let us down. He agreed to a bad deal for the blacks. Economically, we are still on the outside. The economy is very much ‘white.’ It has a few token blacks, but many who gave their lives in the struggle have died unrewarded,” she once stated in an interview. To Winnie, freedom had come at too high a price. She believed that while South Africans had gained the right to vote, they had not achieved true equality; the land, wealth, and power still rested largely in white hands.

Winnie’s criticism rejected what she saw as the moral victory, but economic defeat, of the anti-apartheid struggle. She argued that reconciliation without justice left the structures of white privilege intact, and that the poor, those who had suffered most under apartheid, continued to live in poverty even in the new South Africa. Her frustration reflected the disillusionment many Black South Africans felt, who believed the liberation movement had compromised too easily in its pursuit of peace.

This ideological rift between Winnie and Nelson also revealed their profoundly different approaches to leadership. Nelson Mandela was diplomatic, patient, conciliatory, and focused on building a united nation. Winnie, in contrast, was revolutionary, fiery, uncompromising, and unwilling to forgive the architects of oppression. Where he sought reconciliation, she demanded justice; where he preached forgiveness, she demanded accountability. These differences, magnified by years of separation, ultimately made their reconciliation impossible.

Her outspokenness, often interpreted as bitterness, was rooted in lived experience. Unlike Nelson, who had spent decades behind bars, Winnie had endured the brutal realities of apartheid firsthand in the township’s police raids, solitary confinement, and the daily suffering of the poor. She had seen her community’s continued struggles even after democracy was achieved, and she refused to accept symbolic freedom without material change. Her “anger” and “defiance,” traits that had once made her a hero of resistance, came to be viewed by many within the new political establishment as a liability in the era of reconciliation.

Ultimately, the ideological and emotional distance between Winnie and Nelson Mandela mirrored the broader tensions within post-apartheid South Africa: the conflict between forgiveness and justice, between peace and transformation. Their marriage, once a symbol of unity in struggle, could not withstand the weight of these contradictions.

Yet even in her criticism, Winnie’s voice remained vital. Her refusal to celebrate a freedom that left the poor behind kept alive a necessary conversation about the unfinished business of liberation. In her anger, there was truth — a reminder that political freedom without economic justice was, in her eyes, an incomplete revolution.

less

Conclusion

Winnie Madikizela Mandela was a revolutionary leader, social worker, feminist, and apartheid activist known as the 'mother of a Nation' by her supporters. She worked tirelessly, dedicating her life to the liberation struggle and fight against Apartheid in South Africa while Mandela was in prison. Winnie represents a revolutionary decolonizing feminist; due to this, she could not escape the blatant sexism. The world tried to erase her work by demonizing her and painting her as a radical for her anger towards the injustice faced by her people.

Like any freedom fighter, she took part in necessary violence crucial to the freedom of her people. Actions that her male counterparts are remembered and praised for, she was humiliated and arrested because she was an influential African woman challenging an oppressive system. Winnie Mandela will be honored as an African woman who challenged gender roles and showed that women's place is in the revolution. She earned her ‘Mother of a Nation’ title in her own right and was the most vital voice against Apartheid and the release of Mandela.

Unfortunately, Winnie, like many powerful revolutionary women in history, has gone through the epistemic injustice of having her work, role, and influence undermined, misrepresented, excluded, or even forgotten, especially in a society that managed to forgive apartheid rulers and not the woman who had fought for their freedom. Winnie Mandela stayed true to herself and, in her own words, "I am not sorry. I will never be sorry. I would do everything I did again if I had to. Everything."

less

Glossary

Doeke: primarily a South African term for a square of cloth worn mainly by women to cover the head, often as a cultural or traditional accessory

Creche: In South Africa, a creche is a type of Early Childhood Development (ECD) center that provides basic care and a safe environment for young children, typically from birth to around three years old, while their parents work.

Dompas: In South Africa, the “dompas” (an Afrikaans term meaning “dumb pass” or “stupid pass”) referred to the passbook that Black South Africans were required to always carry under the apartheid regime. The dompas was part of the pass laws, a system of internal control designed to restrict and monitor the movement of Black people within their own country. It contained personal details such as identification information, employment history, and permission from a white employer or government official to enter certain “white” areas.

less

Bibliography

“AUHRM Project Focus Area: The Apartheid.” African Union. https://au.int/en/auhrm-project-focus-area-apartheid

Barbera, Rosemary. “International Social Work Leader Review: Winnie Madikizela-Mandela (1936–2016).” Kendall A. Kendall Institute for International Social Work Education. https://www.cswe.org/getmedia/943cffb2-7091-45b6-9f82-c7c5f582b889/International-Social-Work-Leader-Review_W-Mandela.pdf

Bereseford, David, and Dan van der Vat. “Winnie Madikizela-Mandela Obituary.” The Guardian, April 2, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/apr/02/winnie-madikizela-mandela-obituary.

Bezdrob, A. M. (2003). Winnie Mandela: A life. Zebra Press

Biography.com editors. “Winnie Mandela Biography.” The biography.comwebsite, A&E; Television Networks, August 20, 2020. https://www.biography.com/activists/winnie-mandela

“Community of Brandfort relive Winnie Madikizela-Mandela's exile days.” Sowetan, 2018. https://www.sowetan.co.za/news/south-africa/2018-04-04-community-of-brandfort-relive-winnie-madikizela-mandela-exile--days/

Cordova, Genette. “Winnie Mandela led South Africa out of apartheid and she’s yet to receive proper credit.” Revolt, 2021. https://www.revolt.tv/article/2021-02-23/59129/winnie-mandela-led-south-africa-out-of-apartheid-and-shes-yet-to-receive-proper-credit

Mandela, W. Part of My Soul Went with Him. W. W. Norton & Company, 1985.

Naipaul, Nadria. “How Nelson Mandela betrayed us, says ex-wife Minnie.” The Standard, 2015. https://www.standard.co.uk/hp/front/how-nelson-mandela-betrayed-us-says-exwife-winnie-6734116.html

Phakeng, Mamokgethi. “The Language of True Freedom.” The University of Cape Town News, 2019. https://www.news.uct.ac.za/article/-2019-06-18-the-language-of-true-freedom

Shoofs, Mark. “Lost Opportunity: South African President Hedges on Cause of AIDS, Ignores Access to Medicine.” Village Voice, Durban World AIDS Conference, 2000. https://www.natap.org/2000/durban/dur_rp12village_voice071100.htm

South African History Online. "Albertina Nontsikelelo Sisulu,” 2011. https://sahistory.org.za/people/albertina-nontsikelelo-sisulu.

South African History Online. "Winnie Madikizela-Mandela,” 2011. https://sahistory.org.za/people/winnie-madikizela-mandela.

less

Bio

Nyambura Kinyungu is a dedicated Kenyan social researcher with a passion for socio-economic development, gender equality, indigenous epistemology, feminist studies, ecological sustainability, and social justice. She holds a Master’s degree in Liberal Studies from The New School in New York and a Bachelor’s degree in Law from Riara University in Kenya. Her work explores the intersections of policy, governance, and community-driven solutions to address pressing social and economic challenges. With a keen analytical approach, she has contributed to research projects that inform sustainable development strategies and equitable policymaking. Her research has been featured in a legacy publication from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Kenya, demonstrating her commitment to informing policy and practice through her work.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully