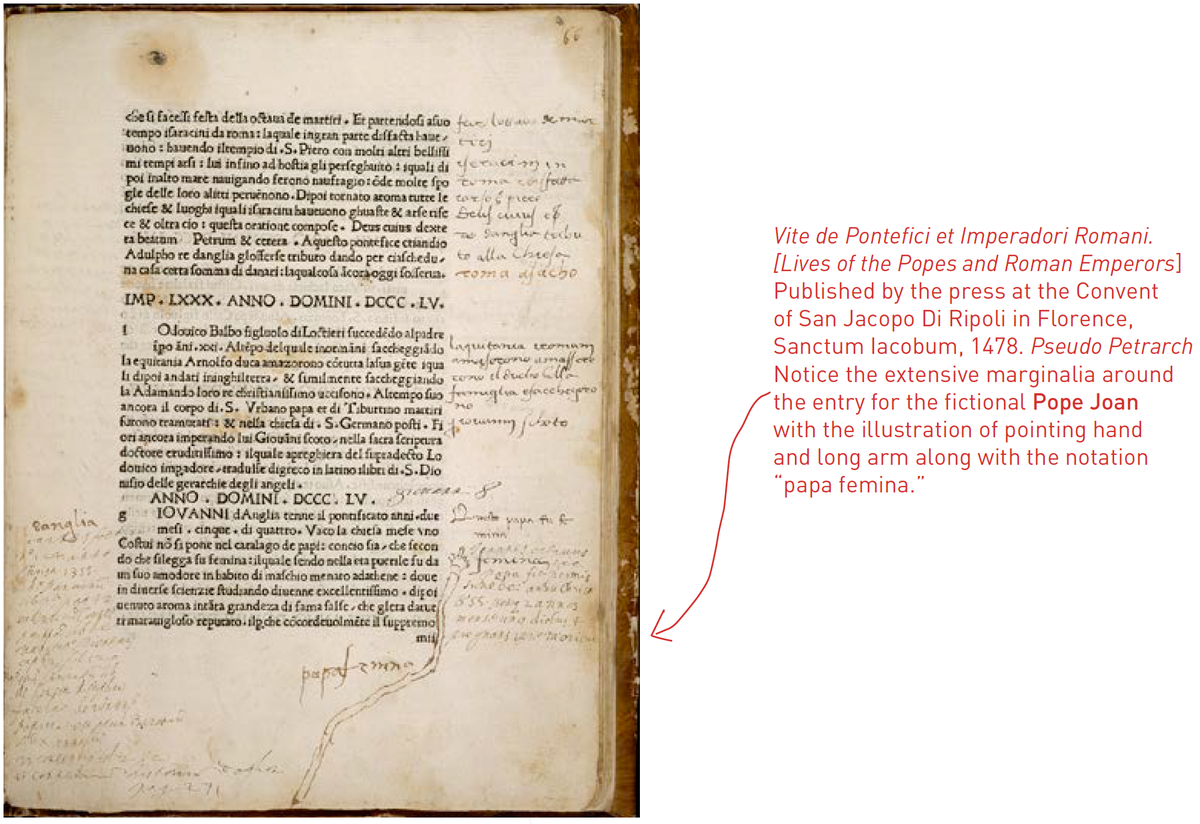

As early as 1476, nuns at the Convent of San Jacopo di Ripoli in Florence, Italy, were setting type. That is only twenty-two years after Gutenberg’s famous “42-line Bible” was printed. The Ripoli press operated for nine years from 1476–1484, producing approximately 100 different titles

(The Examination or Investigation of the World), printed in Mantua

In the German city of Augsburg, Anna Rüger printed Eike von Repgow’s Der Sachsenspiegel, a German law book, in 1484.

Women, family and the press

In a letter, Antwerp printer Christopher Plantin says of his daughters, “I taught them to read and write well so that from the age of four or five until the age of twelve, each of the four eldest, according to age and seniority, has helped us to read the proofs in the printing-shop in whatever script or language they may have been submitted for printing."

Plantin and his wife, Joanna Riviere, ran their shop in Antwerp in the mid-sixteenth century. The Plantin family illustrates the pivotal role women played in keeping the family press running.

The eldest daughter, Margareta, was sent to Paris to train with a calligrapher and married Frans Ravelingen (Raphelengius), a scholarly proofreader and printer who worked for Plantin.

Martina ran the family press in 1567 and was married to Jan Moretus, a Flemish printer. Through Martina, the printing lineage descended through her sons Balthasar I and Jan II, who jointly inherited the shop and press. Their colophons were often signed, “Ioannis Moretis et Martinae Plantinae.” Balthasar I Moretus was good friends with the painter, Peter Paul Rubens, who painted several of the family portraits that still remain in the Museum Plantin-Moretus in Antwerp.

Catharina worked as a successful business woman in the lace and linen trade, negotiating with merchants and handling the movement of products. She married lace merchant Pierre Gassen’s son Jehan in 1571.

Magdalena helped at home with proofreading five to seven languages and assisted in managing the press; she married printer Egidius (or Gilles) Beys.

Henriette married printer Pieter Moretus. Through marrying within the trade and being educated in the business, the women in the Christopher Plantin family and their descendants were able to keep the Plantin-Moretus press operational for three hundred years until 1876.

To read Christine Moog's full treatment of women printers in history, please download the PDF she has created for The New Historia (available above on this page)

Comment

Your message was sent successfully