Pre-Modern

Religion is often thought of as a sphere that oppresses women, but it also served as one of the earliest known spheres of women’s education. While not glossing over the oppression and silencing that did, and do, occur, we find many examples of women who drew on their faith to claim a voice. And these examples now constitute the earliest records of women in history.

In the Buddhist tradition, Sumangalamata (c. 600 BCE) was a member of the earliest community of women followers of the Buddha. Many of these women left accounts of their practice in poems, which were later written down in Pali and collected in the Therigatha. Patacara (c. 500 BCE) was among the female disciples of Gautama Buddha in what is now Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, India, and was known for being a proponent of the Vinaya, the rules of monastic discipline.

Women in Judaism also found voices of authority within religious spheres. Urania, daughter of Abraham, sang before female congregants in Worms. Another cantor, Richenza, is mentioned in The Memorial Book of Nuremberg. Dulcia, the wife of Rabbi Eliezer of Worms, taught women prayer words and songs. Jewish women in Spain during the Inquisition preserved Jewish identity and tradition.

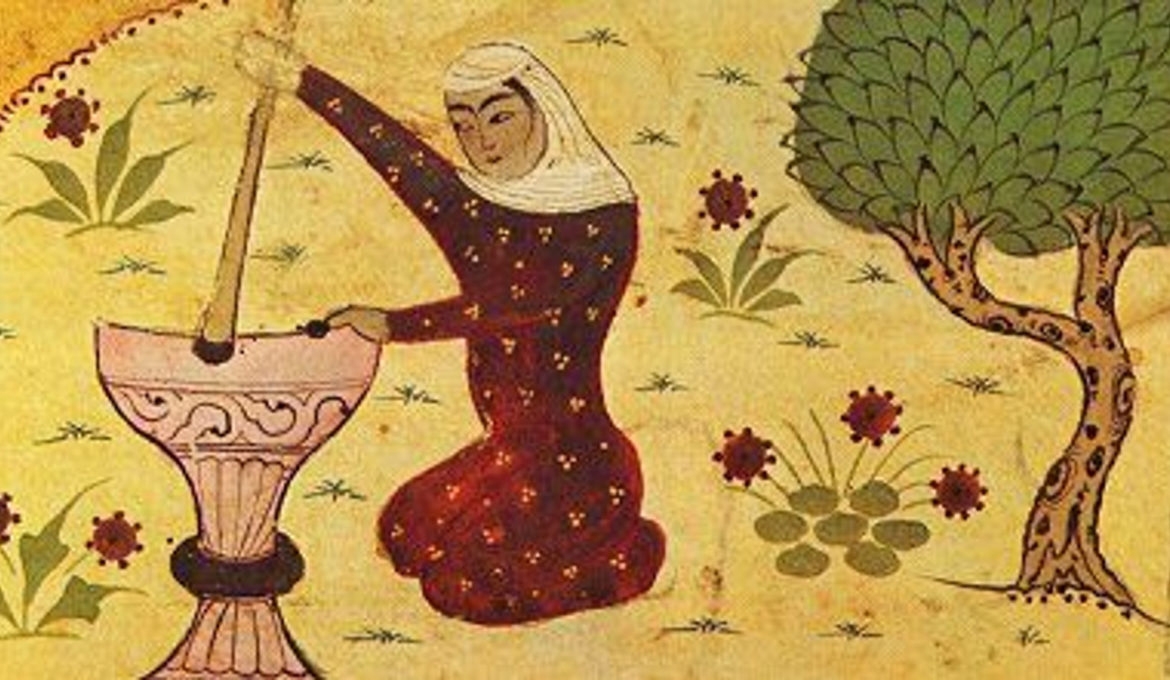

In Islam, Khadija b. Khuwaylid (c. 555-619 CE) was the wife of Muhammad and the first Muslim, known today as the “mother of believers.” Nusayba b. Ka'b al-Ansariyya (d. 634 CE), a companion of Muhammad, was one of the earliest converts to Islam in Medina. She is remembered for participating in the Battle of Uhud (625), during which she shielded the Prophet Muhammad from enemies. Al-Malika al-Hurra Arwa al-Sulayhi (d. 1138 CE) ruled as the queen of Yemen and was well versed in various religious sciences, Qur’an, and hadith, as well as poetry and history. Rabi'a of Basra (c. 714-801 CE) was a Sufi mystic who composed poems of adoration to God.

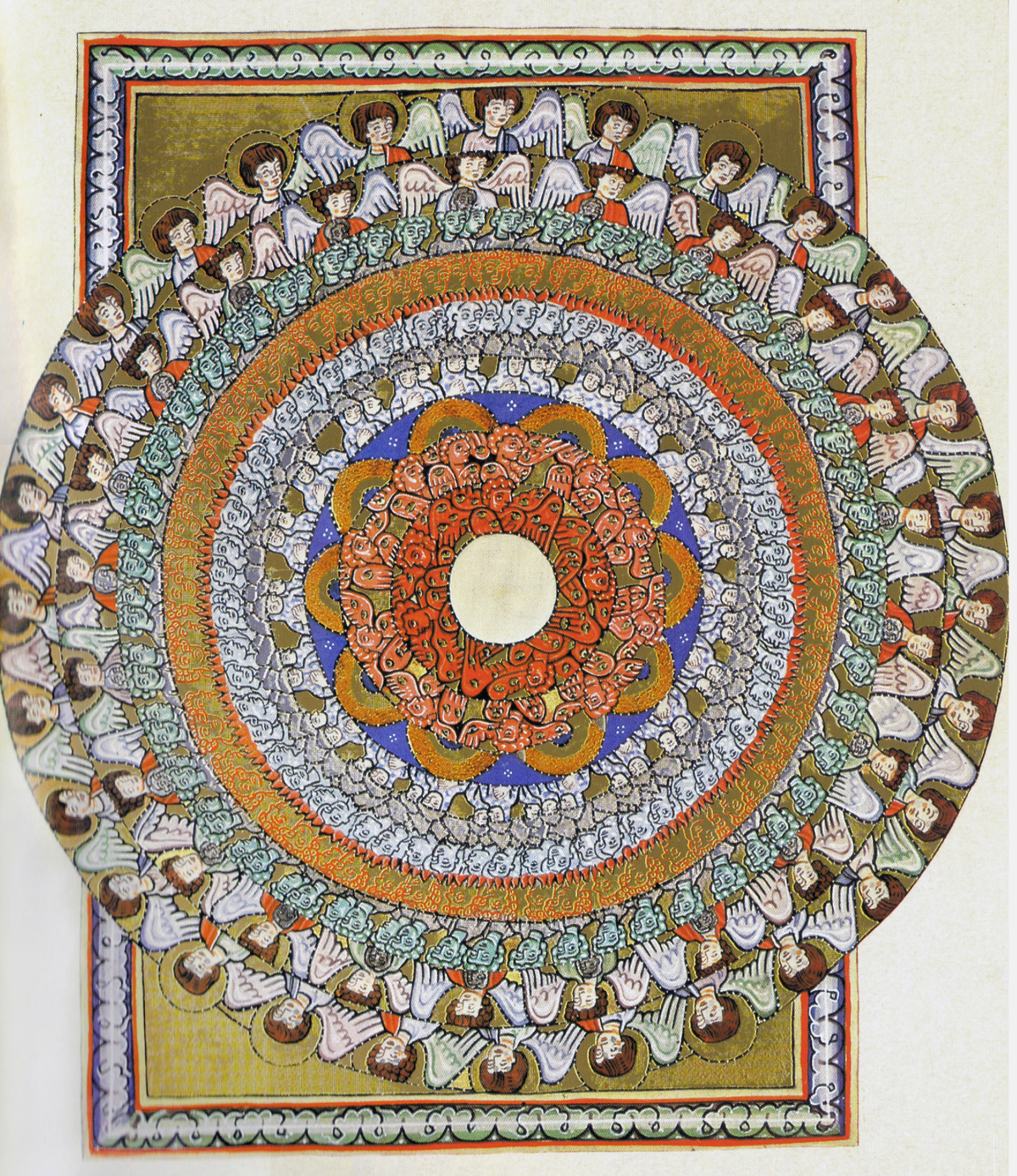

In medieval Christianity, women found access to spiritual and political power through religion. Abbesses like Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179) independently founded and ruled institutions. They wrote religious treatises, poetry, music, and scientific manuscripts. Women claimed access to the divine through mystical visions. Margery Kempe (1373-1438 CE), for instance, left her marriage after having 14 children to pursue a life of pilgrimage and independent devotion, composing her own autobiography.

In the Hindu tradition, bhakti, a form of devotion that emphasizes personal emotional attachment to the divinity, gave women a voice within patriarchal religious structures. Saint-poets like Karaikkal Ammaiyar (c. 400), a devotee of Shiva, in South India; Mirabai (c. 1498-1547) in Rajasthan; and Lal Ded (c. 1320-1392) in Kashmir professed devotion to deities that prompted them to forsake traditional gender norms. They wandered on pilgrimage and composed songs of devotion that still survive today.

less

Modern

In more recent times, women have continued to make inroads, opening up space for women’s voices within religion, and using those voices to speak to issues within and outside of religion.

Feminist theology is found across religions from Judaism to Sikhism and the Baha'i Faith. Such theology seeks to reconsider traditions, practices, scriptures, and theologies from a feminist perspective. The goals of feminist theology include increasing the role of women within the clergy, reinterpreting patriarchal depictions of God, and recovering the historic role of women within the faith.

In the Catholic Church, Mary Daly (1928-2010), a radical feminist and theologian, wrote foundational works in feminist theology. In Islam, women like the scholar Fatema Mernissi (1940-2015) wrote about the power of women within the Muslim faith. Such thinkers have recovered women’s historic central presence within faith and used this to argue for their equality within contemporary religious practice.

Women have also been at the forefront of interfaith alliances. For instance, Joelle Novey, a grassroots environmental activist, has connected religious language with the urgency of climate change and built bridges between congregations, interfaith groups, and environmental activists. Leymah Gbowee, Tawakkol Karman, and Ellen Johnson Sirleaf jointly won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2011; working across Islam and Christianity, these activists campaigned for peace and democracy in Liberia and Yemen.

As the sociocultural anthropology scholar Saba Mahmood (1962-2018) wrote in Politics of Piety: The Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject (2004, revised 2011),

"Agency...is understood as the capacity to realize one's own interests against the weight of custom, tradition, transcendental will, or other obstacles (whether individual or collective). Thus, the humanist desire for autonomy and self-expression constitutes...the slumbering ember that can spark to flame in the form of an act of resistance when conditions permit."

less

To Come...

Schemas to come on this topic include Rabi'a of Basra, Mary Daly, Andal, and Pema Chodron. Existing schemas include Mirabai, Janabai, and Margery Kempe.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully