Birth

Zhu Kerou’s dates are often given as fl. 1127-1162 CE

Education

UnknownDeath

April 8th, 2022Religion

UnknownZhu Kerou was a weaver whose works are the first signed tapestries in China to use tapestry weave to depict pictorial compositions rather than patterns. Her pictorial silk tapestry weavings, kesi 緙絲, created painting-like compositions.

While weaving was often traditionally associated with women and considered feminine work, painting and the making of images was associated with men. Thereby, Zhu’s innovation in using a medium associated with women’s labor to produce images in the style of paintings is ground-breaking on a number of levels.

Personal Information

Name(s)

Zhu Kerou 朱克柔, ming Zhu Qiang 朱強

Date and place of birth

Zhu Kerou’s dates are often given as fl. 1127-1162 CE and it is said that she lived and worked in Yunjian 雲間, today’s Songjiang 松江, a suburb of Shanghai 上海.

Date and place of death

unknown

Family

Mother: unknown

Father: unknown

Marriage and Family Life

unknown

Education

There is no historical information on how Zhu Kerou was educated. Some modern scholars have theorized that she was trained as a painter. Because Zhu Kerou is known only by her weavings, it is clear she was trained as a weaver. The works with her names on them are exquisite and show the work of a very skilled tapestry weaver.

Religion

unknown

Transformation(s)

We have almost no information about the historical woman, Zhu Kerou. However, her works are the first signed tapestries in China to use tapestry weave to depict pictorial compositions rather than patterns.

During the time she was believed to live, the Southern Song dynasty (1127-1279), farming techniques were made more efficient, and silk was produced in abundance. Many weavers, responding to this excess of silk, produced fancy weaves and luxury silk goods. It is possible that Zhu Kerou’s works were a part of the interest in luxury silks during the twelfth century. Her luxury silks were not luxurious weaves for clothing such as gauze or damask, but rather tapestry weave; silk weavings that created images reflectinng the trends in painting at the time. The innovation in her work is the use of woven silk threads to create a painting-like composition.

While weaving was often traditionally associated with women and considered feminine work, painting and the making of images was associated with men. Thereby, Zhu’s innovation in using a medium associated with women’s labor to produce images in the style of paintings is ground-breaking on a number of levels.

less

Significance

Works/Agency

Zhu Kerou is known for her pictorial silk tapestry weavings, kesi 緙絲. Tapestry weave is a type of weave that uses continuous warps and discontinuous wefts to create a reversible image with threads. Tapestry weave techniques had been used in China since the Tang dynasty (618-907). Around the year 1127 CE, during the Song dynasty, we see the shift in the production of tapestry weave reproducing patterned textiles produced with a drawloom to asymmetrical compositions that reflect a knowledge and interest in painted compositions. It has been theorized that Emperor Huizong徽宗 (r. 1101-1126) initiated this shift in conception of what a woven textile could do. However, Zhu Kerou is one of the first artists to weave her signature into such a composition as a weaver. Contemporaneous to Zhu, are a few works incorporating signatures of the painter of an image, woven by an anonymous artisan. Another weaver who includes his signatures in his compositions is Shen Zifan 沈子蕃, who ostensibly worked during the same period as Zhu.

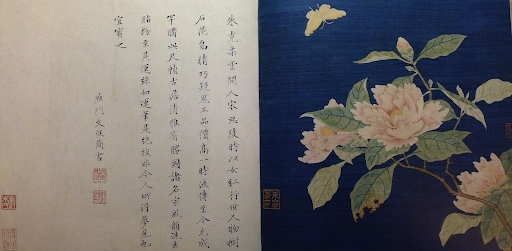

Seven kesi weavings with Zhu Kerou’s woven seal are still extant in Asian collections. Most of her extant works are small-scale, measuring approximately 25 cm square. These include Butterfly and Camellia (Fig. 1) and Peony, both in the collection of the Liaoning Provincial Museum, Shenyang. Her only known large-scale composition, Ducks on a Lotus Pond (Fig. 2), is in the collection of the Shanghai Museum of Art. Wagtail and Polygonum (Fig. 3), Peach Blossom and Thrush, Bird and Flower, and Wagtail, are all in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei.

Two no-longer-extant works are mentioned by Zhu Qiqian in Notes on Silk and Embroidery. These works are titled Citron and Autumn Bird and Lofty Retreat Amid Clouds and Mountains.

Contemporaneous Identifications

Zhu’s weaving, Butterfly and Camellia is mounted next to a laudatory inscription by the well-known Ming painter, Wen Congjian 文從簡 (1574-1648). Wen Congjian was a member of the well-respected Wen family, based near today’s Suzhou, known for painting, calligraphy, and connoisseurship during the Ming dynasty. By writing about Zhu Kerou's weaving on paper mounted right next to the work itself, Wen Congjian embedded it within the same apparatus of textual commentary and appreciation normally associated with the high literati arts of painting, calligraphy, and poetry. This work of weaving becomes part of the literati culture of commenting on works of art, which add to their value by creating a connoisseurial history of those who have appreciated the work. The work is absorbed into the elite male-dominated culture of connoisseurship.

Dorothy Ko has argued that as more women became painters, men began to write about women’s textile work as a woman’s sphere of artistic production, therefore excluding women from the elite male world of painting. Men therefore create gendered spheres of creativity and promoted textiles as the Confucian and proper place for women’s work and artistic endeavors.

Reputation

We have no information about how Zhu Kerou’s work was received during her lifetime. Her name does not appear in local gazeteers. The first known time her name is written and discussed is in a calligraphic inscription written by the above-mentioned Wen Congjian, mounted next to Butterfly and Camellia (Fig. 1a). This inscription is the earliest biographical information we have on Zhu Kerou. The inscription is translated as follows:

Zhu Kerou was a native of Yunjian [Songjiang] and she lived during the Southern Song dynasty. She was famous for women’s work [weaving]. The exquisite skill shown in her works with figures, trees, rocks, flowers, and birds, is almost supernatural. She was highly esteemed during a certain period and her pieces that survive are very rare. This small picture is full of quiet elegance and expresses the taste and culture of a famous artist of the past. It has essential and natural beauty [lit: she has done away with feminine artifice]. Her skill is so extraordinary; she handled the silk as if handling a brush. Her technique was such that people today cannot even dream of seeing [such skill]. This work should be treasured. Written by Wen Congjian of Yanmen.

If we can rely on Wen Congjian’s inscription as based on oral tradition or a no-longer extant text, it states that Zhu Kerou was an admired artist at a certain point in time, but her name had been forgotten by many until the Ming period. During the Ming dynasty, there was an interest in reviving the culture of the earlier Song dynasty, in no small part because the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) between the two was founded by the Mongols, who were seen by Han Chinese as foreign usurpers. Therefore, the Ming elite viewed the Song dynasty as the height of Chinese culture; any work of art dating to the Song was treasured. Many Ming artists emulated earlier Song artists in style.

Since the late Ming, Zhu Kerou’s name had been known in literati circles. Her works were collected by major art collectors of the late Ming and Qing dynasties. Eventually, some of her weavings were incorporated into the imperial collection during the Qing dynasty, demonstrating the appreciation of her work at the highest level of society.

Legacy and Influence

Because Zhu Kerou was not well known to the general population, even of literate and cultured individuals, her work is not widely influential. However, her name has been attached to many later works of kesi in order to give them value. It is a tradition in connoisseurship of Chinese art to attribute works by unknown artists to famous names. Because of this tradition, hand-written labels, likely written by collectors or dealers, on anonymous kesi often carry the name of Zhu Kerou. Contemporary curators and connoisseurs understand this tradition and it is often acknowledged with a sense of humor, however the use of a famous name on an anonymous work demonstrates the power of that name. Zhu’s name has become synonymous with expert weaving in kesi and is used to add value to anonymous works of tapestry. Just one example is the Kesi Tapestry of Duck and Grasses dated to the Qing dynasty in the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., which has been labelled as the “true traces of Zhu Kerou” in the ink-written label pasted to the tapestry’s mounting.

https://asia.si.edu/object/F1918.39/

Zhu’s work is reproduced by contemporary weavers in China. The beautiful compositions of Ducks on a Lotus Pond and Butterfly and Camellia have been reproduced in contemporary weaving workshops for sale to the public. Therefore, the enduring appeal of her carefully crafted compositions is recognized by contemporary artisans and collectors.

less

Controversies

Controversy

A few scholars have proposed verbally (none in writing) that works with the name of Zhu Kerou woven into them date from the Ming or Qing periods, not the Song. It is conceivable that the works bearing her name are later copies or later works altogether.

Another controversial theory is that Zhu Kerou is a fabricated figure, made up by men who were interested in talented women during the late Ming period. As mentioned above, Ming and Qing elite admired and desired to collect works of art produced during the Song dynasty. At the same time, works by talented women were treasured, while women who chose embroidery and weaving as a creative pastime were framed as the most Confucian and therefore to be admired.

less

Bibliography

Sources.

Ko, Dorothy. “Epilogue: Textiles, Technology, and Gender in China,” East Asian Science, Technology, and Medicine no. 36 (2012): 167-176.

Liaoning sheng bowuguan. Huacai ruoying: Zhongguo gudai kesi cixiu jingpin ji 华彩若英: 中国古代缂丝刺绣精品集 (Variegated Colors in Bloom: A Collection of Ancient Chinese Tapestries and Embroideries). Shenyang: Liaoning renmin chubanshe, 2009.

National Palace Museum. Blossoming Through the Ages: Women in Chinese Art and Culture from the Museum Collection. (Qun fang pu: nüxing de xingxiang yu caiyi 群芳譜 : 女性的形象與才兿). Taipei, 2003.

Piao, Wenying 朴文英. “Liang jian kesi mudan shangxi 两件缂丝牡丹赏析 (Appreciation and Analysis of Two Peony kesi),” Wenwu shijie 2001.1: 29-30.

Sheng, Angela. Textile Use, Technology, and Change in Rural Textile Production in Song China (960-1279). Thesis (PhD), University of Pennsylvania, 1990.

Tong Wen’e 童文娥. Weaving a Tapestry of Splendors: Bird and Flower Tapestries of the Sung Dynasty (Kezhi fenghua: songdai kesi huaniao zhan tulu 緙織風華: 宋代緙絲花鳥展圖錄). Taipei: National Palace Museum, 2009.

Tsuan-tsu-ying-hua 纂組英華 Tapestries and Embroideries of the Sung, Yüan, Ming and Ch’ing Dynasties Treasured by the Manchukuo National Museum. 2 vols. Tokyo: Zauho Press, 1935.

Tunstall, Alexandra. “Beyond Categorization: Zhu Kerou’s Tapestry Painting Butterfly and Camellia” East Asian Science, Technology, and Medicine no. 36 (2012): 39-76.

----. “Woven Paintings, Woven Writing: Intermediality in Kesi Silk Tapestries in the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) Dynasties. PhD diss, Columbia University, 2015.

Zhu Qiqian朱啟鈐. Sixiu biji絲繡筆記. (Notes on Silk and Embroidery) Taipei: Guangwen shuju, 1970.

----. Nügong fuzheng lue 女紅傳徵略 (Compendium of Women’s Duties), ed. Meishu congshu, Huang Binhong 黄賓虹and Deng Shi 鄧實, eds. Nanjing: Jiangsu guji chubanshe, 1997, vol. 3: 2400-2421.

Primary and Archival resources (selected):

Attributed to Zhu Kerou (active late twelfth – thirteenth centuries), Butterfly and Camellia, Silk tapestry mounted as an album leaf with inscription by Wen Congjian, 26 x 25 cm, Liaoning Provincial Museum, Shenyang.

Attributed to Zhu Kerou (active late twefth-thirteenth centuries), Peony, Silk tapestry mounted as an album leaf with inscription by Zhang Xizhi, 23.2 x 23.8 cm, Liaoning Provincial Museum, Shenyang.

Issues with the sources

The inscription by Wen Congjian is seemingly authentic to the late-Ming artist, however his knowledge of Zhu Kerou and her work appears in no other extant source before his hand-written inscription on her work. In fact, biographical information on this weaver is so scarce, we know little more about her than her works tell us.

The tapestry weaves themselves are fragile, light-sensitive objects and therefore rarely exhibited. Nor are they compared with other works by the same artist or works of the same time period. Studies in connoisseurship and authenticity of kesi are lacking in the field and numerous kesi are inaccurately dated accordingly to traditional sources.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully