Birth

c. 2900-2800 B.C

Death

c. 2900-2800 B.C

The Ivory Lady was likely a highly respected person within her community, a political leader. In a time when there was no inherited status, she was able to achieve her social position through merit, personal charisma, and sheer hard work. She was buried in the most magnificent tomb of the Copper Age Iberia (3200-2300 BC). The recent discovery of the Ivory Lady exemplifies the breadth of knowledge still to be uncovered concerning women’s roles in prehistory pre-state complex societies.

Personal Information

Name(s)

The Ivory Lady

Date and place of birth

c. 2900-2800 B.C, south of Iberia.

Death and place of death

c. 2900-2800 B.C, south of Iberia.

Life

The Ivory Lady lived almost five thousand years ago in a period that today we call the ‘Copper Age.’ She was part of agricultural and/or herding communities, engaged in craft specialization and with an already established long-distance trade. Although the Copper Age is a long period of around 1000 years, it seems that the time between 30th and 28th centuries B.C. in southern Iberia, where and when the Ivory Lady lived, witnessed a significant increase in social hierarchization. At this moment, some people rose above others, setting up ‘elite’ groups within an increasingly non-egalitarian society. When we compare the Ivory Lady with other Iberian Copper Age burials she stands out as the most prominent person ever to have lived in that period. Thus, the Ivory Lady is clearly a person of this ‘elite’ group that is being differentiated from the rest of the community.

Death

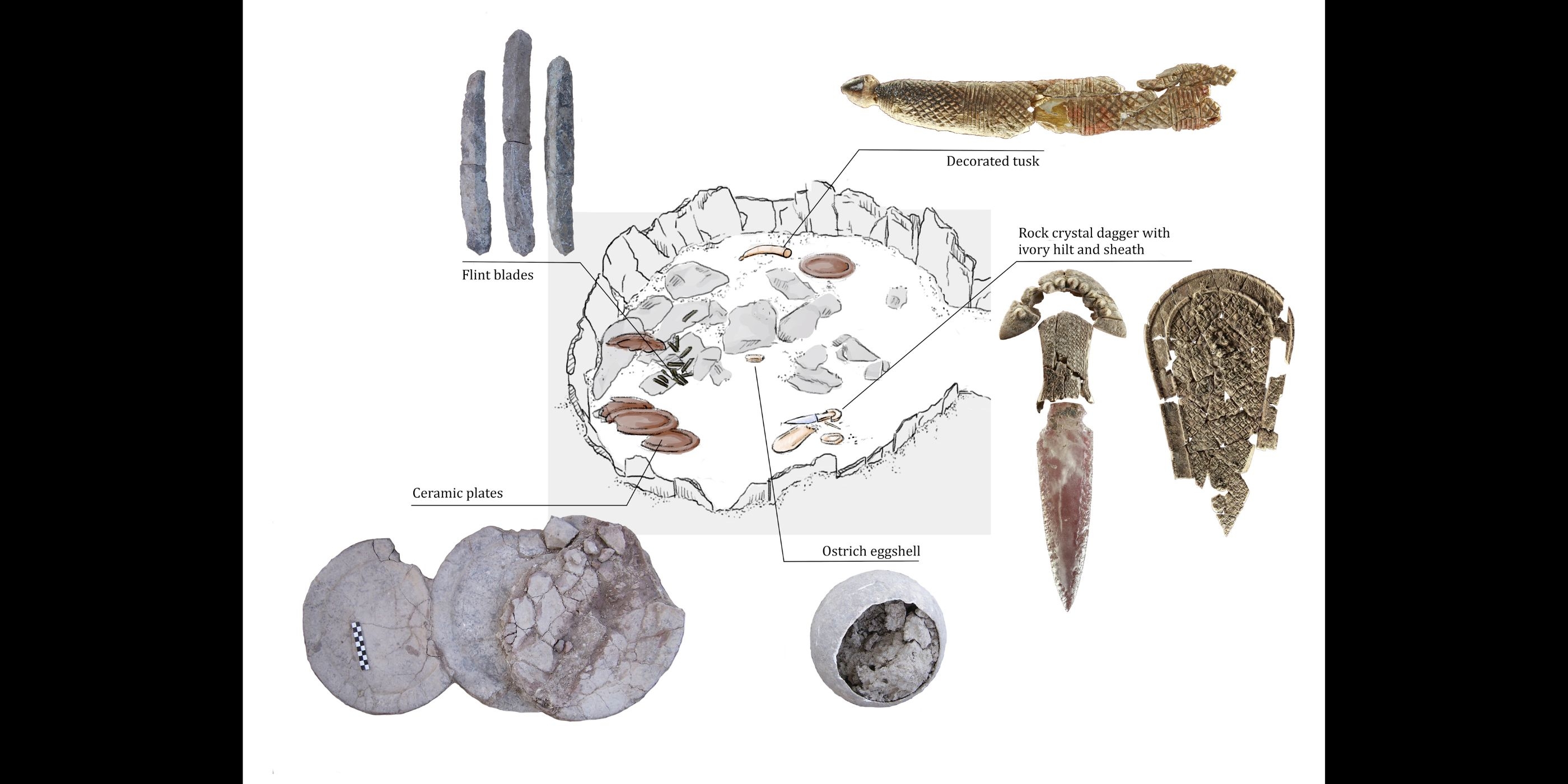

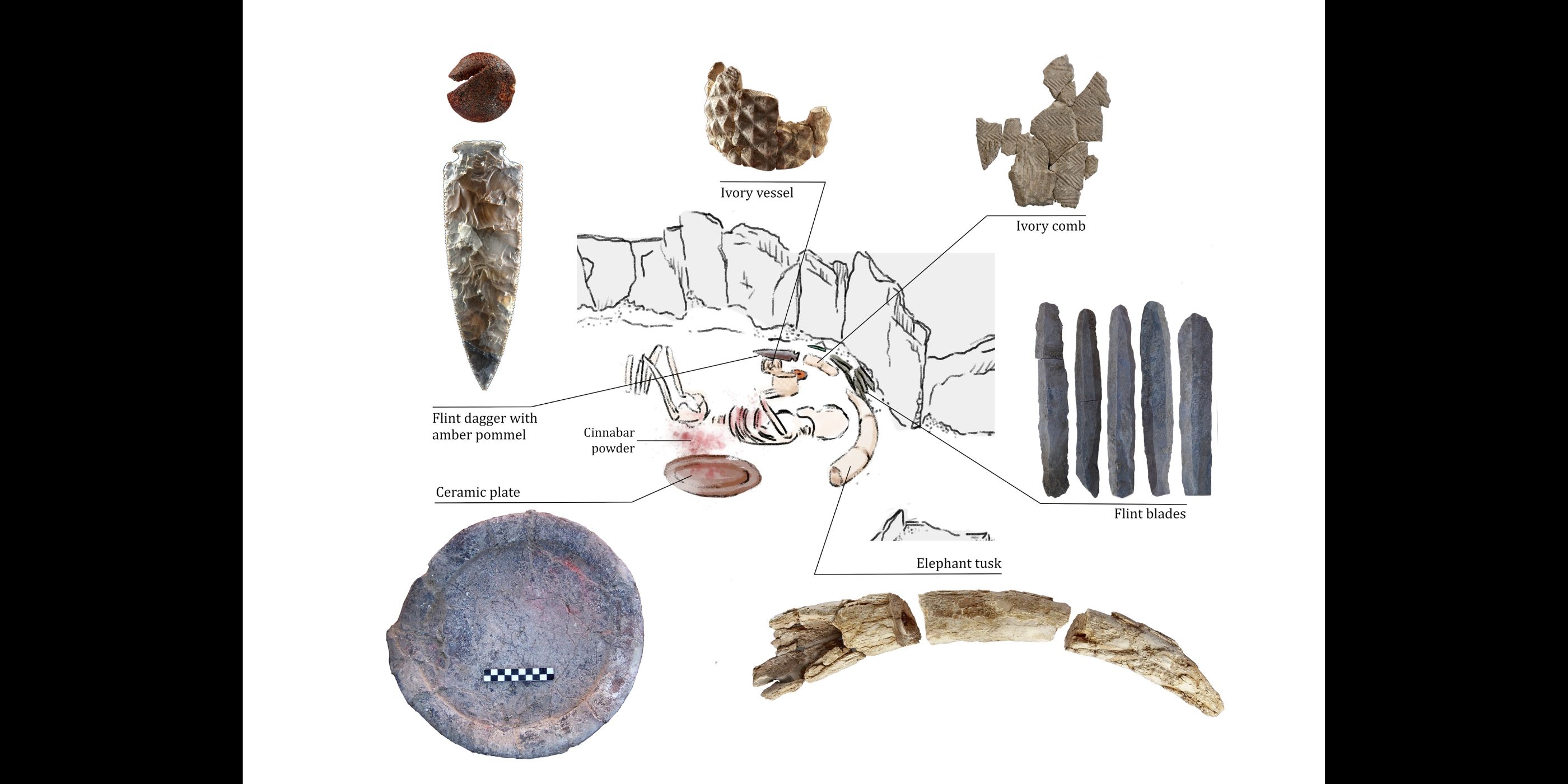

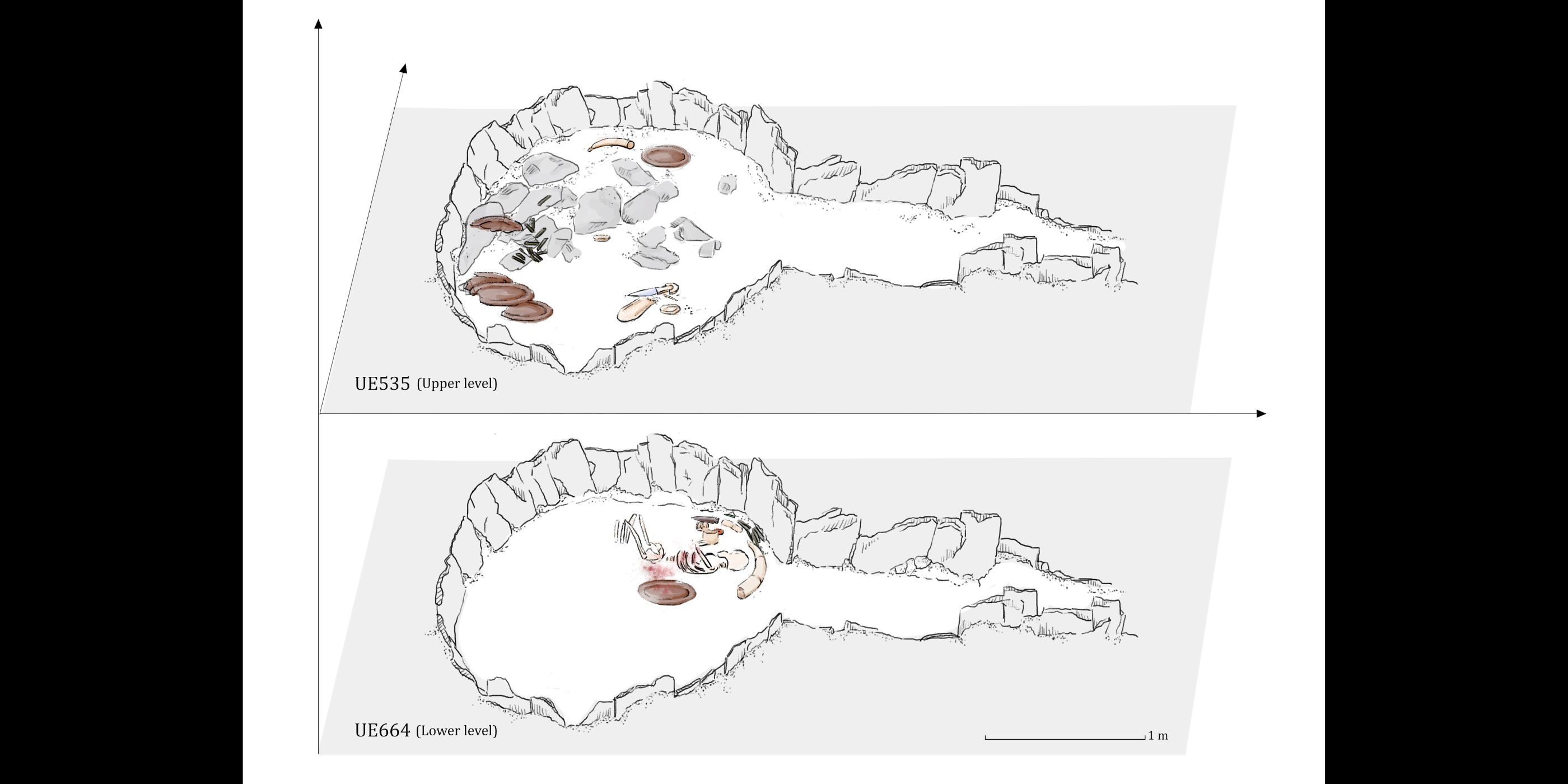

She died between the ages of seventeen and twenty-five sometime between 2900 and 2800 B.C. and she was buried in Valencina, one of the largest sites of the European Copper Age. Her remains were deposited alone in the second chamber of a megalithic monument, a tholos-type structure, together with a lavish set of prestige items.

less

Significance

Social and Cultural Signifigance

The third millennium BC was a time of major transformation. In Mesopotamia and Egypt, the early centuries of the third millennium corresponded to early dynastic polities. In the British Isles, it was the peak time, referring to its formation and use, of Stonehenge, a major megalithic monument and sanctuary. In Iberia, it was a time of increased social complexity, with an intensification of production, greater availability of surplus, a growing inter-regional connectivity, and an increased social inequality and political hierarchisation. The Ivory Lady reflects all these elements, as an emerging leader who did not gain her position by birth (through inheritance) but through personal merit and charisma.

Three kinds of evidence establish that this was a very high-ranking woman. Firstly, the architecture and location of her grave: she was buried in a megalithic tomb which subsequently, and for a period of between 200 and 250 years, became the focus of intense burial and ritual activity, including activity in more than sixty smaller tombs and many deposits in pits. Throughout this long period of time, a buffer or ‘respect’ zone of about twenty-five meters was kept around the ‘Ivory Lady’ grave, which suggests there was an active, orally-transmitted, memory of her.

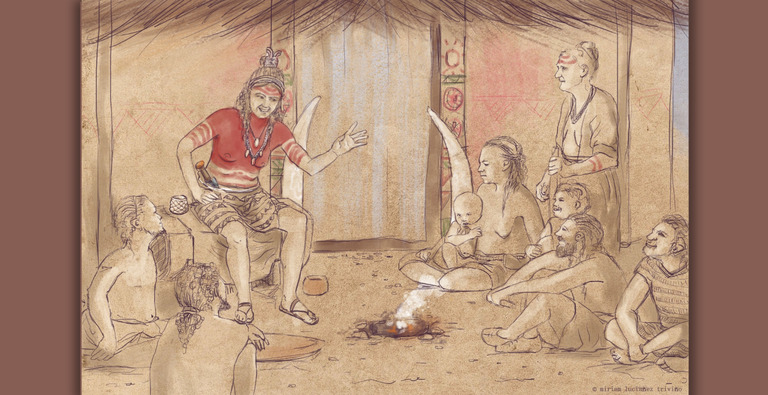

Secondly, two or three generations after her burial, an offering that featured several spectacular artifacts, including a dagger with a rock-crystal blade and ivory hilt, was placed atop her grave. This offering may have been contemporary to the construction of another megalithic burial eighty meters to the south, the magnificent Montelirio tholos, where mostly women were inhumed. Indeed, the grave goods associated with the Ivory Lady and the Montelirio tholos women, exceptional both in terms of quality and quantity, present several elements in common. The builders and users of the Montelirio tholos recognized the Ivory Lady as a prominent ancestor, probably the founder of a clan or kin group they saw themselves as part of.

Thirdly, when we compare the Ivory Lady with other Iberian Copper Age burials she stands out as the most prominent person to have ever lived in that period. I, alongside Leonardo García Sanjuán, Martin Bartelheim, and Miriam Luciañez-Triviño, did a systematic comparison based on a compilation of data for more than 2000 burials to ascertain this.

less

Controversies

This person was previously identified as a ‘likely male’ on the basis of a physical anthropological study published in 2013. The fragmentary state of the skeleton made it impossible to use the metric variables usually employed by anthropologists, so they had to rely on qualitative methods based on the features visible in some of the fragments. The amelogenin peptide analyses has revealed that this identification was wrong and that she was a female. Amelogenin is a structure protein for building up the tooth enamel. Tooth enamel contains isoforms of amelogenin that are sex chromosome-linked, which allows us to determine if an individual is male (XY) or female (XX).

This study sheds new light on a problem we know little about: the social and political role of women in early complex pre-state societies. Usually, the political complexity among pre-state societies involves concepts such as ‘big man,’ ‘chiefdoms’, or ‘aggrandizers.’ All these terms explain the emergence of early forms of leadership by individuals who achieved their status through merit or personal charisma. In ethnographic literature, these leaders are, in most cases, male individuals. Our study shows that this was not necessarily the case in Prehistory, and females may have also occupied high offices as leaders among pre-state societies, which renders women relevant in the analysis of social complexity. In our view, this implies that we need to rethink both what has been said for Copper Age Iberia and also what is assumed about the processes that led to social complexity worldwide.

less

Bibliography

Carrasco, S. R., & Bonilla, M. D. Z. (2013). Análisis bioarqueológico de tres contextos-estructuras funerarias del sector PP4-Montelirio del yacimiento de Valencina de la Concepción-Castilleja de Guzmán (Sevilla). In El asentamiento prehistórico de Valencina de la Concepción (Sevilla): investigación y tutela en el 150 aniversario del descubrimiento de La Pastora (pp. 369-386).

Cintas-Peña, M., Luciañez-Triviño, M., Montero Artús, R. et al. Amelogenin peptide analyses reveal female leadership in Copper Age Iberia (c. 2900–2650 BC). Scientific Reports 13, 9594 (2023).

García Sanjuán, L.; Cintas-Peña, M.; Díaz-Guardamino Uribe, M.; Escudero Carrillo, J.; Luciañez Triviño, M.; Mora Molina, C. y Robles Carrasco, S. “Burial practices and social hierarchisation in Copper Age Southern Spain: Analysing tomb 10.042-10.049 of Valencina de la Concepción (Seville, Spain)”. En: Müller, J.; Hinz, M. y Wunderlich, M. (eds): Megaliths, Societies, Landscapes. Early Monumentality and Social Differentiation in Neolithic Europe, pp. 1005-1037. Frühe Monumentalität und soziale Differenzierung 18/III, Bonn, Habelt.

García Sanjuán, L.; Cintas-Peña, M.; Bartelheim, M. y Luciañez Triviño, M. “Defining the ‘elites’: A comparative analysis of social ranking in Copper Age Iberia”. In: Meller, H.; Gronenborn, D. y Risch, R. (eds.): Surplus without the State. Political Forms in Prehistory, 19 - 21, pp. 311-335. Landesmuseum für Vorgeschichte.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully