Birth

April 8th, 1764 in Château de Villette, 58460 Corvol-l'Orgueilleux, FranceEducation

Home Schooled , Convent Finishing SchoolDeath

November 8th, 1822 in Paris, FranceReligion

AtheistSophie de Grouchy was a philosopher and salonnière of the French Revolution. She translated Adam Smith's The Theory of Moral Sentiments and published this together with her Letters on Sympathy, which paired are works of moral psychology and political philosophy.

Personal Information

Name(s)

Marie-Louise-Sophie de Grouchy, Marquise de Condorcet, known as Sophie de Grouchy, Madame de Condorcet, Citoyenne Condorcet.

Date and place of birth

Born on 8 April 1764, at the Chateau de Villette, near Meulan.

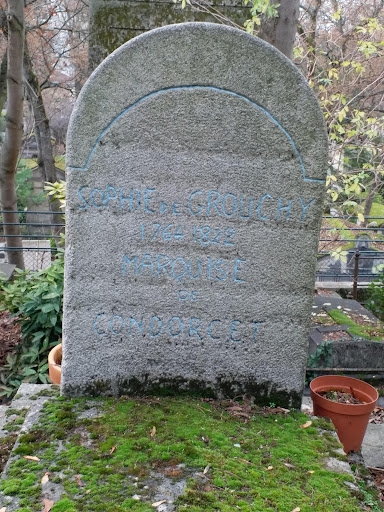

Death and place of death

Died in Paris on 8 November 1822, of unknown disease.

Family

Mother: Marie Gilberte Henriette Fréteau de Pény

Father: Francois-Jacques de Grouchy, 1st Marquis de Grouchy.

Marriage and Family Life

She was the eldest of four. Her sister, Charlotte, remained close to Sophie throughout her life and married Sophie’s close friend and collaborator, Pierre-Georges Cabanis. One of two her brothers, Emmanuel de Grouchy, was held responsible by Napoleon for the French losing the battle at Waterloo.

Siblings: Emmanuel, Marquis de Grouchy (1766-1847), Charlotte Felicie de Grouchy, Madame Cabanis. (1768-1844), Henri-Francois de Grouchy, (1773-1826).

Husband: Marie-Jean-Antoine-Nicolas de Caritat, Marquis de Condorcet (17 September 1743-28/29 March 1794)

Daughter: Alexandrine Louise Sophie de Caritat de Condorcet (b 1790/1-1859), Eliza, married Arthur O'Connor.

At the age of twenty-two she married Nicolas, Marquis de Condorcet, mathematician and philosopher, who held the post of Inspector General of the Mint under Jacques Turgot, economist and, at the time, Finance Minister for France, his mentor and friend. Their wedding was officiated in the chapel of Villette, and the Marquis de Lafayette was their witness. Together they moved to the Hotel of the Mint in Paris, there they started a salon, hosting members of the political and literary international scene. Condorcet was a victim of the Terror–his name was added to a list of outlawed politicians and he went into hiding. In order to protect herself and their daughter, Grouchy and Condorcet agreed that they should officially divorce. Condorcet died in a prison cell in a village near Paris in March 1795. He had run away from his hiding place in order to protect his friends. His body was not identified for another year.

Sophie had two other partners. The first, Mailla Garat was her lover for two years, and he eventually left her for one of her friends. Her third partner, the poet and classical scholar Claude Fauriel, remained with her until her death. He also became a close friend of Cabanis, and collaborated with his widow, Sophie's sister Charlotte, on getting Cabanis’ works published posthumously. Surprisingly, perhaps, Claude and Charlotte did not attempt to collect or publish any of Sophie's own papers (though we suspect there may have been some).

Sophie and her husband had one daughter, born in 1790, Louise Alexandrine, whom they called Eliza. Sophie took Eliza with her in 1792, to demonstrate at the Champ de Mars against the reinstatment of the King. There were other women (including Manon Roland and Olympe de Gouges) and children present at this event which turned to violence when the Marquis de Lafayette, Sophie's friend, ordered his soldiers to charge the crowds of demonstrators.

Condorcet died when Eliza was only five. He left her a very touching letter, offering her advice on life and education and recommending that she read her mother's works on moral education.

In 1805, when Eliza was fifteen, her mother purchased a castle for her in the Loiret, it had belonged to Mirabeau and been sold a few times during the Revolution. Eliza settled there two years later when she married Arthur O'Connor, a friend of the family and Irish sympathiser of the Revolution. The castle is still in the family of the descendants of Eliza, and the self-portrait in pastels of Sophie de Grouchy writing and wearing a feathered hat is exhibited there by the family.

Education

Grouchy was educated at home, benefitting from her brothers’ tutors and her highly cultured mother’s teachings. She was known in her family's circle for her intelligence and studiousness. At the age of fourteen, her uncle compared her writing skills to that of Madame de Sévigné. Later, the same uncle put her in charge of the education of his son–a great mark of trust.

At eighteen, she was sent to a convent finishing school for nobility run by the Chanoinesses of Neuville, in Normandy. There she continued her studies, reading Rousseau and Voltaire and learning English and Italian by translating texts by Young and Tasso. Again, her relatives were duly impressed, thinking her reasoning skills much developed, but worrying that she spent more time with her books than was good for her health. Indeed, she began to suffer with her eyes, a complaint that came back later in life.

Grouchy did not stop studying when she married Condorcet. He and the mathematician La Harpe were both part of a group of intellectuals responsible for founding a society for public education. In 1786, La Harpe lectured on literature, mathematics and Condorcet on Social Sciences. Famous names of the time such as Garat and Marmontel also gave lectures to the society. Topics included botany, biology and physics, and those intereted in the arts could join the Lycee's sister institution, Le Musée. Sophie de Grouchy was an eager participant in these classes, which, together with her looks, earned her the nickname of the "Vénus Lycéenne".

We know that an important part of Grouchy's education was drawing and painting, with the famous Elizabeth Vigée le Brun [comment] as her tutor. The details of this cannot be verified, she might have studied under Vigée le Brun as a child – when the family came to Paris for the winter or a young adult. We know that Vigée le Brun took students reluctantly at her avaricous husband's bidding, and that she did not value them very much. This might explain why there are no records of Grouchy having been taught by her. This part of her education is, however, important, as Grouchy later relied on her artistic skills to support herself and her extended family.

Religion

Grouchy was brought up by a mother who was sincerely religious without being excessively devout. An important part of her religious practice was the charitable visits she conducted, taking her children along for their education, to the poor people of the Villette estate. This ritual features centrally in Grouchy's arguments on sympathy, and particularly, its place in the development of moral faculties. Their religion was also developed on an intellectual level: as a child Grouchy read Marcus Aurelius's Meditations, which were at the time considered enriching for catholic readers. Despite the very liberal nature of her family's religion, Grouchy became an atheist when she discovered the writers of the Enlightenment, in particular Voltaire and Rousseau (although Rousseau himself was not an atheist, many of his followers, including Marie-Jeanne Roland, became atheists after reading his works). Grouchy's religious transformation occurred, paradoxically, while she was at convent school. When she returned home an atheist, her mother was shocked and begged her to burn her works by Voltaire and Rousseau and pray every day to God for her return of her faith. God did not oblige, however, and Grouchy remained an atheist.

Transformation(s)

Grouchy was very much a product of the ideas of the Enlightenment that influenced the French Revolution. As a teenager, she gave up religion and embraced Voltaire, Rousseau, and social justice. Her salon was the heart of the revolutionary faction that had the most contact with foreigners such as Thomas Paine. She was also, through Brissot, and her husband, Condorcet, closely connected to the Girondins and the French abolitionist movement. Although she did not herself write about women’s rights, it is not unlikely that she had some influence over her husband’s short piece on this subject written in 1790: “On the Right of Women to the City”.

Contemporaneous Network(s)

Sophie de Grouchy is often referred to as a salonière, as very often were the women who exercised some influence over intellectual or political progress in the 17th and 18th century. These women are now perceived as having been hostesses, whose job it was to make sure that the men who came to share important philosophical insight in their home did not go about with an empty glass. Famous salonières of the French Revolution include Madame Helvetius, widow of the philosopher of that name, Madame de Stael, Madame Roland, wife of the Girondin minister of the interior, and Sophie de Grouchy. Although all these women were hostesses, their motivation in hosting was perhaps as much the desire to be part of the debate than to facilitate it. It was easier for a woman to talk politics in her own home than anywhere else. Although women could attend men’s clubs – at least until 1793 – in the Assembly, they could only listen. Several of the salonières of the revolution became writers of note, including Madame Roland, Madame de Stael and Sophie de Grouchy. Unfortunately, historians of the revolution, starting with 19th century histrian of the revolution Jules Michelet but continuing to these days, ensured that they only became famous as hostesses rather than as the thinkers and writers they were. Grouchy did host a salon, referred to as a 'cercle' at the time, before during and after the Revolution. But she was very much a participant of the discussions, and on occasions, it was her work that was being discussed.

Like Manon Roland, Olympe de Gouges, Etta Palm D'Aelders and Louise Keralio-Robert, Sophie de Grouchy was associated with the Girondist party and knew its leader, Brissot well.

Grouchy, together with Condorcet, was a member of the Cercle Social, a club founded by the Girondins which encouraged the participation of women. It was at a meeting of this club that Etta Palm d'Aelders presented her feminist text "Discours sur l'Injustice des Lois en faveur des Hommes au dépend des Femmes".

After the Revolution, the surviving Girondins met again in Grouchy's salon, in Paris, Auteuil, and later Meulan, near Villette. The Idealists movement was born there.

Referenced in other female biographies. See Olympe de Gouges, Marie-Jeanne Roland, Madame de Stael, Elisabeth Vigée Lebrun, Etta Palm d'Aelders, Louise Kéralio-Robert.

less

Significance

Works/Agency

In 1791, together with Condorcet, Thomas Paine, the Girondin Jacques Pierre Brissot, and a few others, she started a journal, Le Républicain, designed to raise awareness of republican political thought in France. This journal only lasted a few months as Condorcet demanded it be discontinued after the Champ de Mars massacre, at which Grouchy and her daughter, Eliza, had been present.

Grouchy contributed several pieces to Le Républicain, (unsigned or signed ‘La Vérité- Truth), she also translated others by Thomas Paine. In the first issue she translated two pieces by Paine (one of which is signed Duchastellet, despite having been written by Paine). The third piece in that first issue is signed ‘La Verité’ (Truth) which featured as a signature on Grouchy’s stationery. Stylistically, it appears to have been a collaboration between Grouchy and Condorcet. Its argument is a justification of the revolution to foreigners, an explanation of how the republican principles it embodied contributed to freeing the people of France and how they will, at the right time, do the same for other countries. The main piece of the second issue is the first half of a long paper discussing a letter written by Louis XVI to the people of France before his attempted escape. It offers a republican analysis of the pitfalls of monarchy, even when the monarch in question is not a tyrant. The article was first drafted and later withdrawn by Étienne Dumont it was significantly rewritten using arguments, phrases and style that can be found in the Letters on Sympathy written by Grouchy. The third issue contains the end of that article, another letter by Paine, translated by Grouchy, and a short piece entitled ‘Letter from a young mechanic’ which is unsigned but attributed to Grouchy in which the fictional mechanic proposes that the royal family be replaced by a set of automata. The final issue of the journal contains a long essay on the creation of an electoral council, a piece later reprinted as part of Condorcet’s works.

It was probably around that time that Grouchy wrote the first draft of her Letters on Sympathy, a response and commentary on Adam Smith’s The Theory of Moral Sentiments. The text takes the form of eight letters, addressed to C***. Although some readers have conjectured that C*** was her husband, Condorcet, there is evidence that the letters are addressed to her brother-in-law, close friend and collaborator Pierre-George Cabanis. Cabanis shared an interest with Grouchy on the role of physiology in human behaviour and morality, as well as in social reforms.

The eight letters function like chapters and take the reader through the argument, which starts with the origins of sympathy, and end with the application of the theory developed to social, legal and political reform. Although the format is epistolary, there is no question but that these are not real letters, but the chapters of a short treatise. The argument in sustained throughout the text and the addresses to C*** at the beginning and at the end serve as transition passages from one part of the argument to the other.

The first letter explains how the author is going to depart from Smith’s own argument. Smith, she says, has merely postulated sympathy as a human disposition, but what is needed in order to understand more fully the workings of sympathy is an inquiry into its origins. She then goes on to argue that these origins are physiological in nature, arising from an infant’s first human skin on skin contact (with her nurse) and the discovery of pleasure and pain. The next two letters offer a theory of the development of sympathy through reason, showing how we extend our sympathy to a greater circle as we develop, and distinguish between different sorts of sympathies. Letters IV and V offer an account of the origins of the morality of our sympathy, in which the author mostly agrees with Smith. In the final three letters Grouchy explores the implications of her theory for the legal, social, economic and political reforms called for, and made possible by the French Revolution.

In 1793, the government added Condorcet to a list of men and women who were ‘proscribed’ and had to go into hiding to evade arrest. Condorcet remained in hiding until the Spring 1794, when he attempted to run and died under an assumed name (possibly of poisoning, possibly of a heart attack) in a small town outside Paris. During his time in hiding he completed the introduction to an encyclopedic work on the progress of humanity which he had started several decades earlier. There is evidence that Grouchy helped him with this work during her frequent visits. At the very least, she edited an incomplete manuscript, adding several passages which were deleted by a later editor.

After Condorcet’s death, Grouchy, whose wealth had been confiscated by the State, lived by painting miniature portraits. By the time the Terror was over, she decided to publish her Letters on Sympathy, addressed to her brother-in-law, Cabanis, together with a translation of Adam Smith’s The Theory of Moral Sentiments which greatly surpassed existing translation. This two-volume translation of Adam Smith’s The Theory of Moral Sentiments (TMS) and A Dissertation on the Origins of Languages was published in 1798. Her translation was notable in that it was based on the 7th and most authoritative edition of Smith’s work. Also, unlike previous translations of TMS, Grouchy followed the text closely, without summarizing, interpreting, adding or deleting parts. Her translation remained in print until the late 20th century.

From 1795 until her death in 1822, she dedicated her writing time to editing her husband’s works. But she continued to participate in France’s philosophical life through her salon, and her exchanges with Cabanis whom she saw very regularly, and who worked on physiology and later, Stoicism.

Identifications

Recent work on the Letters on Sympathy, as well as a new translation of that text for the Oxford University Press series, New Histories in Philosophy, mean that Grouchy is beginning to receive more attention from the philosophical community.

Reputation

Sophie de Grouchy was much loved by her relatives and friends, who described her as passionate and very serious. Her detractors thought she was a bad influence on Condorcet, who they claimed would have remained a moderate constitutional monarchist without her. Others said that she had an axe to grind against the royal family because of a slight from Marie-Antoinette, whom she had never met. The royalist press published obscene caricatures and descriptions of her during the revolution.

After the Revolution, Sophie de Grouchy was at the centre of the political group made up of surviving Girondists, including her friend and brother in law Cabanis, Ginguené and Destutt de Tracy. The Coppet circle based at Madame de Stael’s [comment] Swiss home, also became part of her entourage, with Benjamin Constant, Stael's lover, a frequent visitor.

Around that time Grouchy's intellectual reputation grew as she published her translation of Smith along with her Letters on Sympathy. Her work was reviewed very favorably in the periodical, La Decade, and Madame de Stael, with whom she had not been close (mostly because Stael's father, Jacques Necker, had replaced Condorcet's friend and supervisor, Turgot, as Finance Minister before the Revolution) wrote to tell her how much she'd admired the Letters.

Legacy and Influence

Sophie de Grouchy's work and influence is still mostly uncelebrated. The current owners of the castle in which she was born, Villette, commissioned a book about the castle in which she features heavily. But even there she is portrayed as an 'Egeria' of the Revolution, rather than a participant in her own right.

less

Bibliography

Sources

Primary (selected):

Les “Lettres sur la Sympathie” (1798) de Sophie de Grouchy: Philosophie morale et réforme sociale. Ed. Marc-André Bernier and Deirdre Dawson, (Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 2010.

Sophie de Grouchy's Letters on Sympathy, tr. Sandrine Bergès, ed. Sandrine Bergès and Eric Schliesser. Oxford University Press, 2019.

Condorcet: Esquisse d’un Tableau des Progrès de l’Esprit Humain (Paris: Boivin et Cie, 1933).

Condorcet, Paine. Aux Origines de la République 1789–1792. Volume III Le Républicain par Condorcet et Thomas Paine, 1791 (Paris: EDHIS, 1991).

Archival resources (selected):

Some of Grouchy's personal papers, including correspondence can be found at the Bibliothèque de l'Institut: MS 2328 vol I / 511 Papiers Fauriels; MS2475 37.

Web resources (selected):

The first edition of the Letters on Sympathy and Grouchy's translation of Smith is available on Google Books: https://books.google.com.tr/books?id=c-M_AAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=theorie+des+sentiments+moraux&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi25Nb-ua_jAhUrxaYKHb5yCHwQ6AEIOjAC#v=onepage&q=theorie%20des%20sentiments%20moraux&f=false

Madeleine Arnold Tétard has dedicated a blog to Sophie de Grouchy's life (in French): http://sophiecondorcet.canalblog.com

SIEFAR entry by Eve-Marie Lampron http://siefar.org/dictionnaire/fr/Sophie_de_Grouchy

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry, by Sandrine Bergès (forthcoming) https://plato.stanford.edu

'Reappearing Ink' on the Journal of the History of Ideas blog, by Sandrine Bergès, on Grouchy's collaboration with Condorcet. https://jhiblog.org/2018/06/25/reappearing-ink/

Liberty in Thy Name, a blog on women philosophes of the French Revolution: http://www.sandrineberges.com/liberty-in-thy-name

Issues with the sources

Unfortunately, Grouchy's manuscripts have either not survived or not been found. We have a few letters in her hand, either of a personal nature, or on the business of the posthumous publication of her husband's work. In particular, there is no manuscript of the Letters on Sympathy, and editors have to rely on the first edition of that text – printed during her lifetime.

Another issue is that her articles for Le Republicain are unsigned, so that we have to rely on other evidence for authorship attribution, such as Grouchy's correspondence with Dumont, and the fact that La Verité, with which she signed some of the articles, was also printed on her personal stationery.

Finally, although there are good reasons to think that Grouchy participated in the drafting and editing of Condorcet's final work, his Sketch of Human Progress, her contribution was not documented and was eradicated in later editions of that work.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully