Birth

February 5, 1872

Death

October 5, 1931

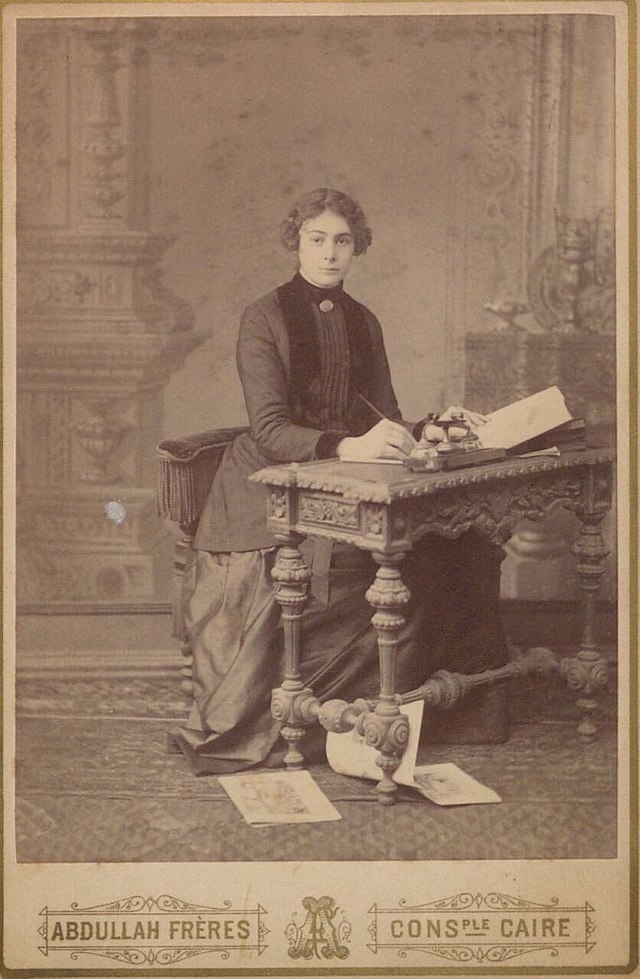

Selma Riza, born in Constantinople, witnessed the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, the birth of the Republic of Türkiye, and was the first Turkish female journalist. She was a fierce advocate for the rights of women, particularly Muslim women, and the lower class.

Personal Information

Name(s)

Selma Riza. Also known as Selma Riza Feraceli or Selma Riza Hanim.

Date and place of birth

February 5, 1872 in Constantinople, Ottoman Empire.

Death and place of death

October 5, 1931 in Istanbul, Turkey. Age fifty-nine.

Family

Mother: Naile Hanim, a native Austrian from a noble family who converted to Islam.

Father: Ali Riza, an Ottoman diplomat stationed in Austria-Hungary and a prominent member of the early Young Turks Turanist Movement.

Siblings

Selma, the youngest of seven, had one sibling of equal fame whose legacy is preserved today. Born in 1858 in Constantinople, Ottoman Empire, Ahmet Riza was Selma’s older brother and role-model.

Since youth, Ahmet was dedicated to advocating for the rights of the oppressed in the Ottoman Empire, particularly the peasantry, farmers, and women. Influenced by his mother who introduced him to Western culture, Ahmet enrolled at the Agricultural Engineering Faculty in Paris. After graduating, he returned and served in the Ministry of Agriculture, hoping to make a tangible impact. Frustrated by the lack of progress, he shifted his focus to addressing inadequate access to education, suspecting it as the primary factor in poverty. Ahmet served as the Director of Education in Bursa for four years before resigning.

In 1889, Ahmet visited Paris, and to prolong his stay, pursued further education. Despite openly criticizing the Empire, the Sultan encouraged his studies and asked him to share his thoughts. In 1894, Ahmet joined the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), also known as the Young Turks, and swiftly gained popularity, becoming the leader. In 1898, Selma, twenty-six years old with a growing interest in her brother’s work, moved to Paris to live with Ahmet. Selma quickly became acquainted with the Young Turks, who welcomed her. Her studies in sociology gained her recognition as “the first Turkish girl to study at the Sorbonne.” She began her journalism career writing for newspapers published by her brother, and was credited as the "first Turkish female journalist," a title associated with her today.

Following the 1908 Young Turks Revolution, Selma returned to the Ottoman Empire, immersing herself in local politics. Ahmet, returning much later, resigned from his career and devoted his time to writing about the CUP and the Young Turks and to completing his memoir. The siblings collaborated in transforming the Adile Sultan Palace into the first high school for girls in the Ottoman Empire, at Ottoman Princess Adile Sultan’s request. 'Adile Sultan İnas Mekteb-i Sultanisi' (Adile Sultan Imperial Girls School) opened in 1916 and was renamed in 1924 and again in 1931 as the “Kandilli High School for Girls,” its present-day name.

Ahmet passed away in February 1930, a year before Selma’s death.

Marriage and Family Life

Neither Selma nor Ahmet ever married or had children.

Selma passed away at fifty-nine. The cause is unknown and reportedly only five people attended her funeral.

Education

Short version: University; degree level unknown.

Long Version: Selma's early education is not documented, but coming from an intellectually inclined family, she likely had private tutors. In 1898, she moved to Paris and studied sociology at the Sorbonne, known commonly as the University of Paris, specializing in women's studies. Given the nature of her work, it is speculated she had some proficiency in Arabic, Persian, and French despite writing only in Ottoman Turkish.

Selma viewed education as a critical resource and advocated for its accessibility, focusing on greater access for the lower class and women.

Religion

Selma, a Muslim and women's rights advocate, challenged misconceptions of Islam as oppressive towards women. She claimed corrupt rulers exploited Islam to justify discriminatory policies and criticized Ottoman Sultan Abdülhamid II (1842-1918) for withholding rights mandated by Islam from Ottoman Muslim women.

Early Life & Transformation(s)

Selma’s upbringing influenced her democratic and liberation values. Inspired by her brother, Selma joined Ahmet in Paris. Ahmet introduced Selma to the Young Turks/CUP, the primary organization at the time advocating for the region now known as Turkey's state liberation, democracy, and modernization. She became a respected member, refining her knowledge through her work, education, and experiences in advocacy.

Selma began writing for the French edition of the newspaper Meşveret, titled in French Mechveret Supplément Français, published by her brother and Halil Ganim Bey, and Şura-yı Ümmet, a Turkish newspaper published by Samipaşazade Sezai, Bahaeddin Şakir, and her brother. The lack of censorship allowed Selma to explore her ideas and develop well-informed beliefs, serving as the foundation for her later works and marking the beginning of her extensive career in journalism.

Exactly when Selma became committed to feminism is unknown, however, her early advocacy and strong views suggest a longstanding commitment. Selma delivered her first lecture after Ahmet introduced her to Maria Pognon, president of 'La Ligue Française pour le Droit des Femmes' (The French League for Women’s Rights). Fluent in French and embodying the "modern Ottoman Turkish Woman," Selma challenged stereotypes of Ottoman women, impressing her guests and earning their respect. Her lecture drew the attention of Lady Aberdeen, President of the International Council of Women (ICW), prompting the start of their relationship.

Selma returned to the region now known as Turkey in 1908, remaining active in her Parisian pursuits while developing interest in Turkish organizations. She broadened her career as the general secretary of the Hilal-I Ahmer Society (Kizilay/Red Crescent Society) and wrote for feminist newspapers such as Hanımlara Mahsus Gazete (Women’s Newspaper) and Kadinlar Dunyasi (Women’s World).

While there, she maintained correspondence with the ICW. Between 1909-1911, the ICW sought to establish a regional council in the Ottoman Empire and Selma accepted the title of Honorary Vice-President for Turkey. Selma was favored for the position by prominent members, including Evelyn Gough, secretary of the ICW, Mrs. Bowen, wife of the director of the American Bible house in Istanbul, Alice Salomon, corresponding secretary of the ICW, and Sophie Sanford who previously met Selma during a tour of Turkey on behalf of the ICW, describing her as having “a charming personality.”

Selma’s upbringing suggests she encountered less sexism and violence in comparison to other women in Turkey. Regardless, her work emphasized equality and inclusivity for all women and she remained unwavering in her beliefs.

Contemporaneous Network(s)

Despite limited and contradictory information, historical accounts depict Selma as well-liked and popular. Her outspoken nature and extensive work positioned her as one of the few spokeswomen during the Ottoman Empire who represented Ottoman women to a broad audience.

Selma’s network expanded significantly in Paris with her brother’s efforts, and Selma was the first female member of the Young Turks/CUP. Selma furthered her network and gained recognition among international feminists and organizations. During her tenure with the ICW, Selma initially wrote with enthusiasm but grew frustrated and critical of the continuing neglect of Muslim women. In 1924, both Selma and Turkey were omitted from the ICW reports and it’s unknown whether she stayed in touch with her collaborators.

Selma was applauded by many, including feminists, journalists, academics, and politicians, for her expansive work. Claude Farrère, a French writer and friend of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the first president of the Republic of Turkey (1923), commended her contributions. Other prominent women of the era, including writers Fatma Aliye, Mihri Nisa, Nigar Hanim, and Nasip Hanim, expressed pride in Selma for her work. Renowned Turkish writer and Selma’s close friend, Samipaşazade Sezai Bey, described her as the "crown of womanhood." Selma’s position as the general secretary of Kizilay established her as a political figure and activist. Her proactive advocacy led to an exclusive women's lecture in Üsküdar, Turkey, after meeting with Mary Mills Patrick, the principal of the American College for Girls. The event prompted the formation of a women's rights advocacy committee in Turkey. Selma also participated in interviews, including one with English author and anthropologist Ethel Stefana Stevens, discussing the impact of political climates on women.

Her articles on the liberation of Turkey and women were popular, marked by controversial and thought-provoking content, earning her the title of “Turkey’s first female journalist.”

less

Significance

Works/Agency

Selma’s Paris lecture "Legal Conditions of Turkish Women," praised former Sultan Abdülmecid and the Tanzimat Reforms (1839-1876) for catalyzing the liberation of Turkish women and founding the first girls’ primary and secondary schools, while criticizing Abdülhamid II and establishing her political stance. She encouraged European feminists to support Turkish women in claiming their rights granted by Islam, sparking controversy. Interpretations ranged from Selma suggesting the Islamic rights of women surpassed those in contemporary Europe to portraying Oriental women as equals to Western women. Overall, the speech succeeded in uniting Western and Muslim women for the women’s liberation cause.

In early correspondences during her tenure with the ICW, Selma struggled to reconcile modernization with local customs in Turkey. In her first official 1910 report, Selma doubted the readiness for change amidst a tumultuous political climate. As Turkey’s conditions worsened, her correspondences became sporadic, and between 1912 and 1913, she didn’t submit a report due to “wartime activities and personal bereavement.”

A German journalist and member of the Osmanlı Müdafaa-i Hukuk-u Nisvan Cemiyeti (Ottoman Organization for the Defense of Women’s Rights), Odette Feldman, wrote a letter in February 1914 criticizing the Turkish council for not reporting on the Balkan War’s impact on women. Odette referenced Selma, urging the Turkish council to comply with the ICW requirements to retain membership. Selma’s response criticized ICW's silence during the war but also sought support. Selma’s subsequent correspondences ceased seeking support, reporting exclusively on issues concerning Muslim women. Between 1920 and 1924, the ICW received no reports or correspondence from Selma, yet she retained her title until 1923. In 1924, Selma and Turkey disappeared from ICW reports, marking the end of documented correspondence with the organization.

Selma’s intersectional work in politics and women’s rights expanded outside of the ICW. She was invited to the League of Nations in Geneva following her compelling letter on the refugee influx into occupied Istanbul, including worsening living conditions and violence against women, but she was denied permission to travel. She served as the general secretary of Kızılay for five years, playing a key role as a founding member, with plans devised by Professor Besin Omer Pasa and colleagues. In 1913, Selma resigned due to her criticism of the administration and their disregard for her concerns. The society rejected her resignation, urging her to continue, which Selma ignored. Selma also established the official Women's Branch of CUP, titled “The Ladies’ Society of Union and Progress.”

Her journalism elevated her to public acclaim. Her articles, featured in popular newspapers including the illustrated, in-color women's newspaper Kadinlar Dunyasi, played a vital role in communicating innovative ideas to the public during this influential period.

At the age of twenty, Selma wrote two novels but only one has been recovered. Uhuvvet' (Brotherhood) was published in 1999 by the Ministry of Culture and translated into modern Turkish by Nebil Fazil Alsan. Believed to have refrained from publishing the novel because of threats from Sultan Abdulhamid II, Selma preserved it as an unpublished manuscript. The novel’s discovery earned Selma the "first Turkish female novelist" title, discrediting previous title holder Fatma Aliye Hanim. Set during Sultan Abdulmejid's Ottoman rule, the 472-page fiction depicts the lives of two women from different socio-economic and political backgrounds and explores topics including arranged marriages, girls' education, social enlightenment, and the urgent need for gender equality.

Reports indicate Selma wrote poems, letters, and notes. The poems were lost, and only a small selection of letters have been preserved. The notes published reveal her strong sense of patriotism.

Reputation

Selma’s journalism career overlapped with a period in history during which newspapers’ played a crucial role in disseminating new ideas to the masses. Intellectuals of the time praised journalists for their efforts and Selma was an exemplary figure. Her multilingualism, education, composure, and advocacy made her well-liked.

Selma died aged fifty-nine; the cause remains undisclosed. Her small funeral sparked speculation and her marital status stirred discussion posthumously. Honored with titles, she likely retained recognition for some years, but she was later forgotten. Some argue that Selma withdrew from work after her return from Paris. Others believe she was overshadowed by her brother's achievements.

Legacy and Influence

Despite Selma’s revolutionary work and fame, her legacy was not well preserved. Limited sources and contradictions in information make ongoing research difficult. Her neglect is often attributed to the patriarchal society she lived in. Additionally, English-written sources occasionally misgender Selma, possibly due to translation discrepancies from Turkish, a non-gendered language, to English, a gendered one.

Despite her historical obscurity, Selma has been esteemed by scholars globally. German feminist Kathe Schirmacher analyzed Selma’s work in her 1905 book Modern Women's Rights Movement, later translated into English in 1912. In February 1994, a noteworthy article about Selma appeared in the Turkish magazine Skylife Subat, illuminating her achievements and featuring a 1917 letter to Samipaşazade Sezai Bey. This letter was her response to his article "Poetry and Woman," which she begins by asking, “My esteemed brother, can you imagine a woman without poetry?” Her letter intertwines knowledge and emotions, symbolizing her tireless efforts in advocating for the liberty of women.

It is noteworthy that recent years have witnessed growing efforts to rediscover and highlight Selma’s contributions, particularly within academic feminist circles.

less

Controversies

Controversy

Selma’s title as "the first and only female member of the Young Turks/CUP" is debated. While her CUP membership is officially recognized, reports of other women covertly affiliated with the CUP, like Emine Semiye Hanim, have been discovered. Her title neglects these secret members and overlooks the Women’s Branch of the CUP, potentially fostering division and reinforcing harmful notions of inferiority between the branches.

Selma’s relationship with the ICW also became strained when her inclusionary advocacy for women shifted to exclusively focusing on Muslim women. Frustrated by the ICW’s lack of support for Muslim and Ottoman women, Selma severed ties with the organization, revealing an early divide in feminism between the East and West and exemplifying stereotypes of Muslim women hindering potential unity within the movement.

less

Clusters & Search Terms

Current Identification(s)

Ottoman/Turkish Feminists, Turkish Female Journalists

Clusters

The Young Turks, International Council of Women (ICW), Ahmet Riza, First Turkish Female Journalist, Selma Riza Feraceli

Search Terms

Early Ottoman Feminists, Journalism in Ottoman Empire/Turkey

less

Bibliography

Sources:

“Ahmet Rıza.” Wikipedia, n.d. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ahmet_R%C4%B1za.

“Ali Rıza Bey.” Wikipedia, December 2, 2023. https://tr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ali_R%C4%B1za_Bey.

Arslanbenzer, Hakan. “Ahmet Rıza: Founder of Young Turk Intellectual Tradition.” Daily Sabah, September 6, 2019. https://www.dailysabah.com/portrait/2019/09/06/ahmet-riza-founder-of-young-turk-intellectual-tradition.

Aytaç, Bedrettin. The Question of Women in the Works of Selma Riza and May Ziadeh. Ankara Üniversitesi Dil ve Tarih-Coğrafya Fakültesi Dergisi , 2002.

Charyyeva, Jennet, Jung Heun Yang, Nil Nazzal, Rawan Hammoud, and Selbi Ereshova. “The Untold Story of an Inspiring Woman: Selma Rıza.” Bilkent University - Institutional Repository, 2020. https://repository.bilkent.edu.tr/items/9b378357-c625-4ab4-8b8c-501f5de9bb7a.

Cinkılıç, Zeynep. Women’s Movement in the Ottoman Empire, n.d.

Demirhan, Ansev. “‘We Can Defend Our Rights by Our Own Efforts’: Turkish Women and the Global Muslim Woman Question, 1870-1935,” 2020.

Doğan, Rumeysa Betül, and Mustafa Yahya Metintaş. Selma Riza Feraceli (1872-1931) and the First Experience of the Turkish Woman As Journalism . Eskişehir Osmangazi Üniversitesi Türk Dünyası Uygulama ve Araştırma Merkezi Yakın Tarih Dergisi , 2017.

“İlk Türk Kadin Gazeteci̇: Selma Riza Feraceli .” Kadın Dostu Markalar, January 22, 2022. https://www.kadindostumarkalar.org/yazilar/ilham-veren-kadinlar/ilk-turk-kadin-gazeteci-selma-riza-feraceli.

İstanbul Kadın Müzesi - Selma Rıza feraceli, n.d. http://istanbulkadinmuzesi.org/en/selma-riza-feraceli.

“Kandilli Anatolian High School for Girls.” Wikipedia, February 5, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kandilli_Anatolian_High_School_for_Girls.

Karavar, Nesrin. “Adile Sultan, A Mystical and Rebellious Ottoman Princess.” IEMed, n.d. https://www.iemed.org/publication/adile-sultan-a-mystical-and-rebellious-ottoman-princess/.

Os, Nicolina Anna Norberta Maria Van. “Chapter Two: Ottoman Muslim Women and the International Women’s Movement .” Essay. In Feminism, Philanthropy and Patriotism: Female Associational Life in the Ottoman Empire, 2013.

“Selma Rıza Biography - Turkish Novelist (1872-1931).” Pantheon. https://pantheon.world/profile/person/Selma_R%C4%B1za/.

“Selma Riza Hanim, İttihat ve Terakki’nin Tek Kadin Üyesi Mi?” Kent ve Bellek, May 5, 2021. http://www.kentvebellek.com/selma-riza-hanim-ittihat-ve-terakki-nin-tek-kadin-uyesi-mi_14.html.

“Selma Rıza.” Wikipedia, May 4, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Selma_R%C4%B1za.

Tekeli, Hasan Safa. “İlk Türk Kadın Gazeteci: Selma Rıza.” Journo, March 8, 2022. https://journo.com.tr/ilk-turk-kadin-gazeteci-selma-riza.

Toros, Taha. “Ilk Türk Kadin Gazateci /First Turkish Female Journalist .” Skylife Şubat, February 1994.

TÜRKOĞLU, Hülya SEMİZ. “İlk Türk Kadın Gazeteci ‘Selma Rıza Feraceli.’” İletim, March 15, 2021. https://iletim.istanbul.edu.tr/index.php/2021/03/08/ilk-turk-kadin-gazeteci-selma-riza-feraceli/.

Üçer, Merve Betül. “Ahmed Rıza.” İslam Düşünce Atlası, n.d. https://islamdusunceatlasi.org/ahmed-riza/7328.

İsmayıl, Kürşat. “İlk Türk Kadın Gazeteci: Selma Rıza .” QHA Kirim Haber Ajansi, August 8, 2023. https://www.qha.com.tr/kultur-sanat/ilk-turk-kadin-gazeteci-selma-riza-468888.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully