Birth

December 5, 1865, Springfield, Massachusetts

Education

Brackett School for Girls, New York City. BA, Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts

Death

December 14, 1934, New Canaan, Connecticut

Religion

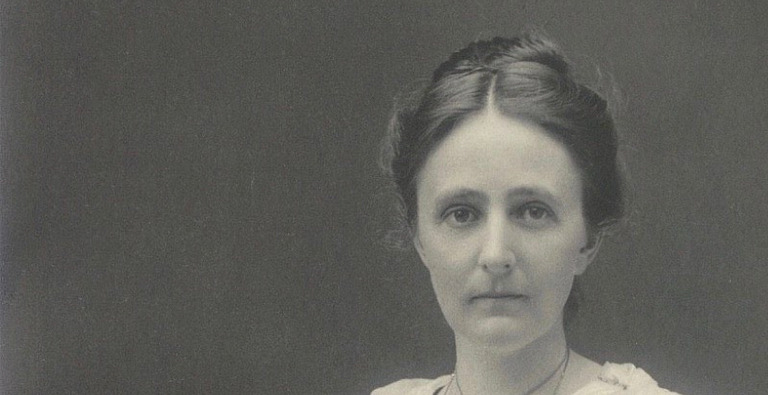

UnitarianRuth S. Baldwin was the co-founder of the National Urban League and one of the unknown Founding Mothers of The New School. She was a social activist fighting for the rights of women and Black Americans.

Personal Information

Born

December 5, 1865, Springfield, Massachusetts

Died

December 14, 1934, New Canaan, Connecticut

Mother: Mary Sanford Dwight Schermerhorn

Father: Samuel Bowles

Marriage and Family Life

Ruth was one of seven children (three others died in infancy), raised by spiritual-but-not-religious parents committed to the common weal. Her mother, Mary (1827-1893), was “a member of the great Dwight family of the Connecticut Valley,” as one obituary put it; her parents were Henry Van Rensselaer Schermerhorn and Hannah Buckminster Dwight. She was remembered as “a member of the Church of the Unity, and always interested in its various works of usefulness in the community…. [She was] warm and impulsive…. [but] exhibited at times a stern moral indignation at willful errors.” Ruth’s father, Samuel (1826-1878), kept a higher profile and was well known as an avid traveler, editor of the influential Springfield Republican and one of the leading abolitionists of his day. He was also a close friend of the poet Emily Dickinson, who shared some of her poems with him and exchanged letters with him and with Mary.

Two years out of college, Ruth married a fellow Unitarian, William H. Baldwin, and shared his commitment to education for women and Black people. They raised two children (a third died in infancy): Ruth, who attended Smith College and married the painter John Folinsbee, and William H., Jr., a Harvard graduate like his father and a public relations pioneer who was active in the National Urban League. Ruth was a mentor to two nephews, Roger N. Baldwin, who went on to help found the ACLU, and Chester Bowles, a founder of the advertising firm Benton & Bowles who was later a diplomat, ambassador, and member of Congress. He also served as Governor of Connecticut and helped desegregate its National Guard.

Education

If it’s true that Ruth’s father was “unusually liberal on the question of women’s careers,” as one account would have it, he may have wanted to broaden her education and worldview. He had gone to work for his father’s newspaper so young he missed college himself altogether. It’s also possible that Ruth’s mother, Mary, wanted more for her than a high school degree. They sent Ruth off to New York City to attend the progressive Brackett School for Girls, founded by Anna Brackett, a philosopher, the editor of a book of essays on education, and an outspoken advocate of women’s education who was “quite critical,” one account tells us, “of young girls sitting and sewing days on end—referring to that as ‘insanity.’” (Anna Brackett was among those who contributed homages to Mary after her death, suggesting the two women got to know one another).

Ruth then attended Smith College, an experience she so enjoyed that she stayed on for two years as secretary to the President and later became the first female trustee. Along the way, she persuaded her husband, by then a rising figure in the railroad industry, to join her in championing Smith. Although he died before he had a chance to see it, his donations helped finance a dorm, dubbed Baldwin House.

Religion

Ruth and William were social-reform-minded Unitarians.

Transformation(s)

Ruth was raised by abolitionists at the height of the movement and was no doubt aware of the role women played in promoting the cause. She also benefited from educational opportunities that were unusual for women at the time. When her children were still young, she became involved in her civic-minded husband’s chief causes—broadly, education for African Americans, specifically the Tuskegee Institute and its founder, the Black scholar Booker T. Washington; secondarily, women’s education and Smith College—and continued his work after his death at age forty-two. She remained a close friend of Washington’s and joined other causes, including ones led by outspoken women like Frances Kellor, a prominent social worker and muckraker who among other things helped found a league aimed at protecting vulnerable African American women newly arrived in New York.

In 1910, five years after her husband’s death, Ruth joined forces with the Black sociologist George Edmund Haynes to create what became the National Urban League. It soon established affiliates across the country and became a quiet force in the drive for equal opportunity.

Ruth was influenced by the progressive movement of the early 20th century. She was a member of the Socialist party and a pacifist who publicly opposed World War I. She supported the labor union movement, rallied around creation of The New Republic magazine, helped found the progressive New School for Social Research, and toward the end of her life helped launch the Highlander Folk School, a community organizing training center committed to social justice and equality.

less

Significance

Reputation

Ruth was prominent enough to be mentioned in the contemporaneous press. Some of this had to do with her husband’s high profile and wealth. She remained active in the National Urban League during a key period of its growth but chose to step down from the board in 1915, having earned a reputation for fairness and a commitment to slow but steady social progress. She saw racial justice as a win-win proposition and was often quoted as having said, “Let us work, not as colored people, not as white people for the narrow benefit of any group alone, but together, as American citizens, for the common good of our common city, our common country.” The Urban League has kept Ruth’s name alive—it invited one of her great-granddaughters to tell Ruth’s story during a centennial celebration in New York City, in 2010—but she has largely been forgotten.

Legacy and Influence

Ruth’s influence could be felt in her son William’s lifelong activities on behalf of the Urban League, and also in the work of her nephew Roger N. Baldwin, who credited her with raising his awareness of social justice issues and prodding him the direction that ultimately led to the founding of the ACLU. Ruth was “the most important” of the many women who influenced him, Roger told one biographer, adding: “My almost saintly Aunt Ruth was an endless source of comfort and inspiration to me. She was wise, selfless, and sensitive. She shared my radicalism, but in her own more respectable way.” Another nephew and mentee who acknowledged her influence, Chester Bowles, worked for world peace, equal opportunity, and workers’ rights.

less

Controversies

Controversy

The leading Black intellectual of Ruth’s time, W.E.B. Du Bois, moved away from the Urban League and Booker T. Washington to form the more political NAACP. This rift called into question the “accommodationist” approach of the Urban League—at a time when systemic racism and even lynchings were widespread.

New and Unfolding Information and/or Interpretations

The single most important tool in uncovering her life has been the internet, which surfaces everything from PhD dissertations devoted to her father’s influence to newspapers.com links to articles about Ruth’s involvement with the National Urban League. With the reopening of public libraries, including the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York City, some information, especially about her father’s influence, remains to be read and interpreted.

less

Bibliography

Online:

EmilyDickinsonMuseum.org/samuel-bowles

engagedscholarship.csuoo.edu/etdarchive/243

sophia.smith.edu/blog/smithpedia

newspapers.com

HutchinsCenter.fas.harvard.edu/web-dubois

thoughtco.com/african-american-womens-history-timeline

columbia.edu/cu/web/archival/collections/lpdp

nps.gov/articles/nationalurbanleagu

The Public (journal), Vol 21. 1918

newrepublic.com/article/153050/intellectual-roots-new-republic-magazine

Silo.pub/Roger-nash-baldwin-and-the-american-civil-liberties-union

wikiwand.com/en/Chester_Bowles

loc.gov/resource/rbpe

Books:

The National Urban League, 1910-1940, by Nancy J. Weiss. Oxford University Press, 1974

Roger Baldwin: Founder of the American Civil Liberties Union, by Peggy Lamson. Houghton Mifflin, 1976.

Defending Everybody: A History of the American Civil Liberties Union, by Diane Garey . TV Books, 1998.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully