Birth

September 7, 1533 at Greenwich Palace

Death

March 24, 1603 at Richmond Palace

Elizabeth I, the last Tudor monarch, was Queen of England and Ireland. She sought to return England to Protestantism from Catholicism. She is regarded as one of England's greatest monarchs, with her reign often referred to as a Golden Age in British history.

Personal Information

Name(s)

Elizabeth Tudor, Queen Elizabeth I

Date and place of birth

September 7, 1533 at Greenwich Palace.

Death and place of death

March 24, 1603 at Richmond Palace.

Family

Queen Elizabeth I’s father was the formidable Henry VIII (1491-1547), who became the king of England in 1509 at seventeen years old. Henry married the widow of his elder brother Arthur Tudor (1486-1502). She was Catherine of Aragon (1485-1536), daughter of the Spanish monarch's King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella. Catherine was a popular and effective queen, but her position was weakened when her only child to survive infancy was a daughter, Mary I (1516-1558). In order to divorce and remarry, Henry broke with the Catholic Church. In 1533, Henry’s new archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556), declared the marriage to Catherine null and void, allowing for Henry to marry the pregnant Anne Boleyn. Henry was convinced this child would be a son, but the child, born September 7, 1533, was another daughter, Elizabeth I. After two more miscarriages, Anne was accused of having taken five lovers, and she was executed. Henry then married Jane Seymour (1509-1537), who bore the King’s first male heir to survive infancy, Edward VI.

Careful political maneuvering was required to elicit a break with the Roman Catholic Church and to make Henry the Supreme Head of the new Church of England; this maneuvering was accomplished by Thomas Cromwell (1485-1540), the king’s chief counselor and Lord Privy Seal; Cromwell was also in charge of the dissolution of the monasteries across England.

Cromwell was later executed by Henry VIII on charges of usurping the king’s authority, treason, and heresy, but the charges came during a time when Henry VIII was unhappy in his marriage to his fourth wife, Anne of Cleves (1515-1557), a marriage Cromwell negotiated. After the marriage to Anne of Cleves was annulled, Henry married Katherine Howard (1524-1542). She was accused of unfaithfulness and was also executed. Henry’s last marriage was to Katherine Parr (1512-1548).

Despite having both daughters, Mary I and Elizabeth I, declared illegitimate, Henry’s will stated that if Edward VI died without heirs, the crown would go to Mary, and if she died without heirs then the crown would pass to Elizabeth. Henry died at Whitehall on January 28, 1547.

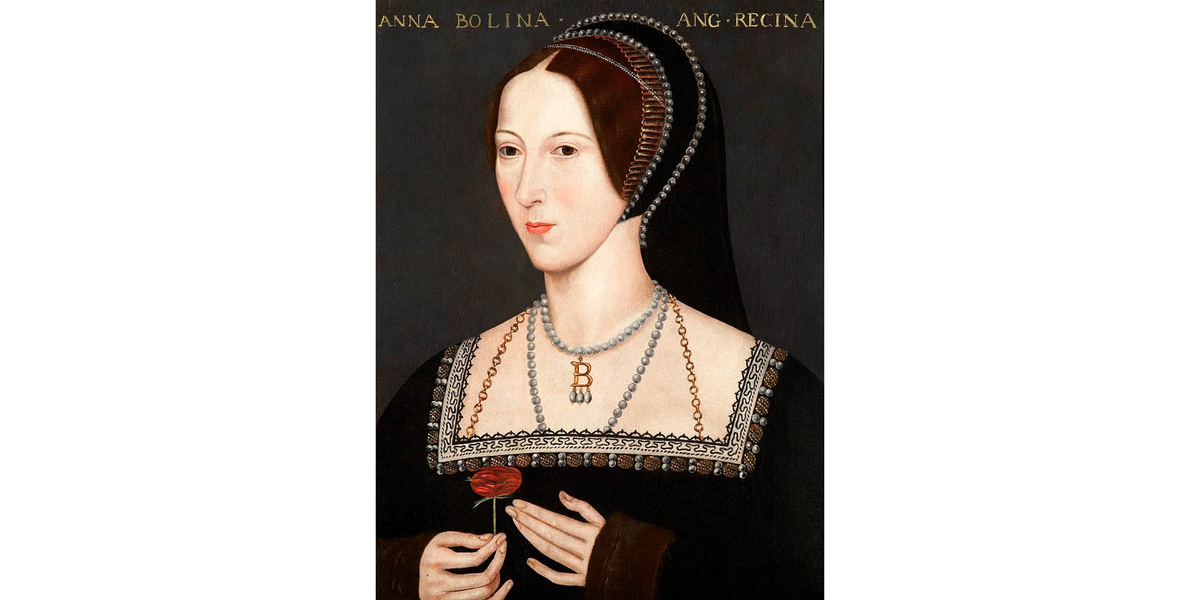

Mother:

Elizabeth I’s mother was Anne Boleyn. Anne was born between 1501 and 1507. She was the daughter of Thomas Boleyn and his wife, Elizabeth Howard. In 1513, she was sent to the Low Countries to join the household of Margaret, Archduchess of Austria (1480-1530). She later went to France to attend Henry VIII’s sister Mary (1496-1533) while she was the queen to King Louis XII of France. After Louis’s death, Anne stayed at the French court to serve the new queen, Claude of France (1499-1524), who was very fond of her. In late 1521, she returned to England and was placed at Henry’s court. By 1526, when Henry was already considering ending his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, he fell in love with Anne Boleyn. In 1532, Henry made her Marchioness of Pembroke in her own right and they finally had full sexual relations. When Anne became pregnant, Henry was committed to having what he was sure to be his son be born in wedlock. After breaking with the Catholic Church and having his marriage to Catherine of Aragon declared null and void, Henry married Anne. But he was disappointed that their child was another girl, Elizabeth. Anne was also in conflict with his chief minister Thomas Cromwell, as she wanted the funds from the dissolution of the monasteries to help the poor instead of enriching the crown. As queen, Anne also pushed for an official translation of the Bible into English. After two more miscarriages, Henry became convinced that Anne had seduced him into marriage by witchcraft and that she had taken five other lovers. She was executed on May 19, 1536.

Brother:

Elizabeth I’s brother on her father’s side was Edward VI. The four-year-old Elizabeth was at Edward’s christening, and during Henry’s reign they spent a fair amount of time together; during this time, it appears Elizabeth and Edward were fond of each other. This closeness ended after the nine-year-old Edward became king in 1547. After this, Elizabeth was seldom allowed to visit him at court. In July 1553, Edward grew ill. As he lay dying, probably on the advice of John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland (1502-1553), he wrote a will that changed the succession from the will of Henry VIII. He removed his sisters, Mary and Elizabeth, from the line of succession.

Edward, who was not of age and did not have the force of parliament behind him, attempted to disinherit both of his sisters on the grounds of Mary’s Catholicism and Elizabeth’s capacity to marry a foreign Catholic prince, despite her being Protestant herself. Edward’s cousin, Lady Jane Grey (1537-1554), who Edward and his counselors wanted the crown to pass to, was already married to the English Protestant Guildford Dudley (1535-1554), son of the Duke of Northumberland. When Elizabeth heard how ill her brother was, she tried to see him at court but was turned away by Northumberland. Following Edward’s death, which was kept a secret, Northumberland sent messages to Mary and Elizabeth, as if from Edward, begging them to come to him. Mary, realizing the message was a trap, declared herself Queen and raised an army. Mary was widely supported. She became queen without battle. Jane’s rule lasted only nine days.

Sister:

Elizabeth I’s sister on her father’s side was Mary I. Mary was born in 1516. She was devoted to her mother Catherine of Aragon and, like her mother, never accepted that Henry and Catherine’s marriage was not valid and that she was a bastard. She hated Anne Boleyn, who supplanted her mother and had mixed feelings about Elizabeth. When Elizabeth was a child, during the time following Anne’s execution, Mary was kind to her.

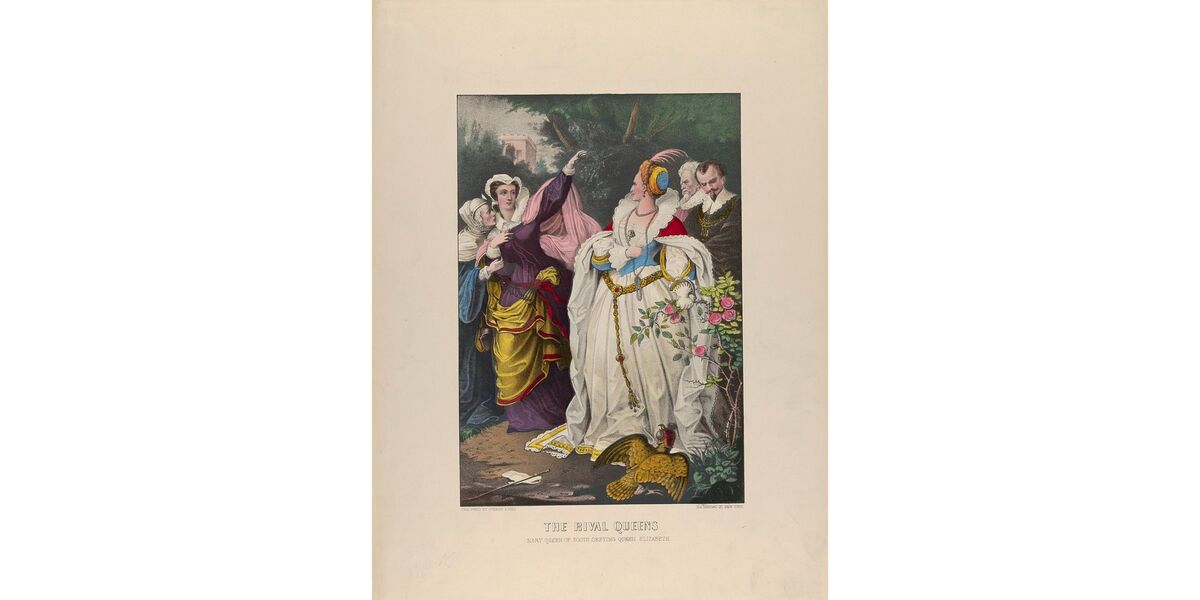

When she became queen in July 1553, she greeted Elizabeth exuberantly. Elizabeth and Henry’s one surviving wife, Anne of Cleves, rode in the carriage behind Mary in the procession to her coronation. But Mary grew angry with Elizabeth when she refused to fully accept Catholicism. This anger led her to claim Elizabeth had no right to the throne, that she was the child of Anne Boleyn and Mark Smeaton, a musician who was executed under suspicion of being Anne’s lover. In 1554, Thomas Wyatt, English soldier and conspirator against the crown (1521-1554), rebelled against Mary because of her marriage to Prince Phillip of Spain (1527-1598); after this, Mary, who feared Elizabeth was plotting against her, subjected the princess to house arrest at court and later sent her to the Tower. Despite conflict, Mary’s husband Phillip thought Elizabeth a better heir than Mary’s Catholic cousin Mary Stuart (1542-1587), who was married to the heir to the French throne, Francis II (1544-1560). At that point in history, France and Spain were enemies and Phillip was thinking in the interest of his home country. At Philip’s encouragement, there was a reconciliation between the two sisters. After Mary’s death in November 1558 there was a peaceful transition to Elizabeth.

Marriage and Family Life

Elizabeth never married, and although there were many rumors, she never had children.

Education

Queen Elizabeth received an impressive education, but because she was not expected to become queen, she never received an education in the art of ruling. Her first governess was Katherine Champernowne Ashley (1502-1565)–commonly known as Kat. She joined the young Elizabeth’s household in 1536. She worked with Elizabeth to instill manners and good behavior. Thomas Wriothesley, the 1st Earl of Southampton (1505-1550), wrote to Thomas Cromwell in 1539 that when he was at Hertford Castle to visit the Lady Mary, he also saw the six-year-old Elizabeth, “who replied to the King’s meassage with as great gravity as [if] she had been 40 years old. If she be no worse educated that she appears she will be an honour to womanhood” (State Papers Online). Ashley worked with Elizabeth on needlework, embroidery, music, dancing and riding, as well as reading and writing, and the study of history and geography. She also taught Elizabeth elementary Latin. Jean Belmaine taught her French, and Battista Castiglione taught her Italian.

In 1546, when Elizabeth needed more advanced training, William Grindal (d. 1548) became her tutor. She continued her Latin, began Greek, and also focused on ancient history, rhetoric, and mathematics. Tragically, in January, 1548, Grindal died of the plague. Fourteen-year-old Elizabeth insisted that Roger Ascham, respected British humanist and scholar (1515-1568), be her next tutor. He is especially known for his work with her on double translation–translating a text of Latin or Greek into English, and then translating it back into the original language. Her language study by this time also included Spanish. By 1550, he was no longer part of Elizabeth’s household. But when Elizabeth became queen, she would often do translations with Ascham in the evening for pleasure. In regards to Elizabeth’s intelligence and learning, Ascham wrote:

"It is your shame, (I speake to you all, you yong Ientlemen of England) that one mayd should go beyond you all, in excellencie of learnyng, and knowledge of diuers tonges. Pointe forth six of the best giuen Ientlemen of this Court, and all they together, shew not so much good will, spend not so much tyme, bestow not so many houres, dayly orderly, & constantly, for the increase of learning & knowledge, as doth the Queenes Maiestie her selfe. Yea I beleue, that beside her perfit readines, in Latin, Italian, French, & Spanish, she readeth here now at Windsore more Greeke euery day, than some Prebendarie of this Chirch doth read Latin in a whole weeke. And that which is most praise worthie of all, within the walles of her priuie chamber, she hath obteyned that excellencie of learnyng, to vnderstand, speake, & write, both wittely with head, and faire with hand, as scarse one or two rare wittes in both the Vniuersities haue in many yeares reached vnto" (Ascham 1570).

This quote was taken from Roger Ascham's book on education The Scholemaster, for which his wife Margaret Ascham wrote the preface.

Two instances, in particular, exemplify the excellence of Elizabeth’s education. In 1544, when she was eleven, Elizabeth translated Marguerite of Navarre’s Mirror of a Sinful Soul (1531) from French to English as a New Year’s gift to her step-mother Katherine Parr. She not only demonstrated her skills as a translator but also her exquisite italic handwriting and her skills as an embroiderer, creating beautiful front and back covers for the book. The following year she translated Katherine’s prayers into Latin, French, and Italian for her father Henry VIII and again embroidered beautiful covers. Elizabeth continued her education for the rest of her life, reading and translating for pleasure.

Religion

Elizabeth’s father Henry VIII broke with the Catholic Church after failing to convince Pope Clement VII (1478-1534) to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, with whom he had no surviving sons, only a daughter, Mary. In 1533, Parliament declared that “this realm of England was an empire,” and neither Pope nor Holy Roman Emperor could tell its king or its people what to do. That year, Henry married the object of his affection, the by-then pregnant Anne Boleyn, who was sympathetic to reformed ideals. To Henry’s disappointment, Anne gave birth to Elizabeth instead of a son. She was executed three years later. Henry’s next queen Jane Seymour gave Henry the son he craved, the future Edward VI and died after childbirth. Both children were raised as Protestants. During Henry’s reign, the official religion ebbed and flowed between Reformed beliefs and practices and those belonging to Catholicism.

During Edward VI’s reign, those in power pushed for the state church to more strictly embrace Protestantism, which would have made the young Elizabeth comfortable. Despite this, the next monarch, Elizabeth’s Catholic half-sister Mary Tudor, reinstated Catholicism and obedience to the Pope in England. Mary implored Elizabeth to convert to Catholicism, but Elizabeth, refusing to convert, asked instead to leave the court. During Mary’s reign, Elizabeth was put under house arrest and imprisoned in the Tower of London, fearing for her life throughout the ordeal. In the last three years of Mary’s reign, over three-hundred Protestants were burned as heretics. When Elizabeth became queen in 1558, England became Protestant again; she took her coronation oath of office on an English Bible. When Parliament argued a queen could not be the Supreme Head of the Church, Elizabeth agreed to act as Supreme Governor instead, but she also decided no human could hold the title of Supreme Head, a role she determined belonged only to Christ. As Supreme Governor, Elizabeth adopted all the same responsibilities as the Supreme Head, effectively acting as the head of the Anglican church. Though Protestant, Elizabeth’s England allowed for Catholic rituals so long as the theology was ultimately Protestant. No Catholics were executed in the first decade of her reign, and she hoped that Catholicism would die out on its own.

In 1568, the Catholic problem grew more complicated when Elizabeth’s Catholic cousin Mary Stuart fled Scotland for England. Potential plots against Elizabeth and tensions, between the strong Catholics on one side and extreme Protestants–Puritans–on the other, increased as her reign progressed. Elizabeth wanted outward conformity, but she had no desire to force her subjects into revealing their secret beliefs and concerns. Sir Francis Bacon wrote that Elizabeth strongly believed “consciences are not to be forced, but to be won and reduced by the force of truth, by the aid of time, and the use of all means of instruction or persuasion.” He continued with, “Her majesty not liking to make windows into men’s hearts and secret thoughts, except the abundance of them did overflow into overt and express acts and affirmations, tempered her law, so it restraineth only manifest disobedience” (Bacon 1861, 178). Despite the religious divisions England experienced, the country suffered far less than most other sixteenth-century nations. By the end of her reign, England truly was a Protestant nation.

Transformation(s)

Elizabeth’s life was long and filled with transformations. The first occurred when she was three years old and her mother was executed. The child, observant and intelligent, asked why she was Princess Elizabeth one day and Lady Elizabeth the next. During her brother Edward’s reign, Elizabeth also faced danger. After the death of her father, Elizabeth lived with her stepmother, Katherine Parr, and her new husband Thomas Seymour (1508-1549), brother of Henry VIII’s former wife Jane Seymour. Elizabeth was later accused of relations and a possible pregnancy with Seymour. Seymour was executed for treason, but Elizabeth managed to make her way safely through the scandal. Still, she continued to face danger. When her sister Mary Tudor reigned, Elizabeth was imprisoned in the Tower of London, and the Spanish Ambassador, Simon Renard (1513-1573), tried to convince Queen Mary to have her sister executed. At the age of twenty-five, after these traumas, she became queen of England.

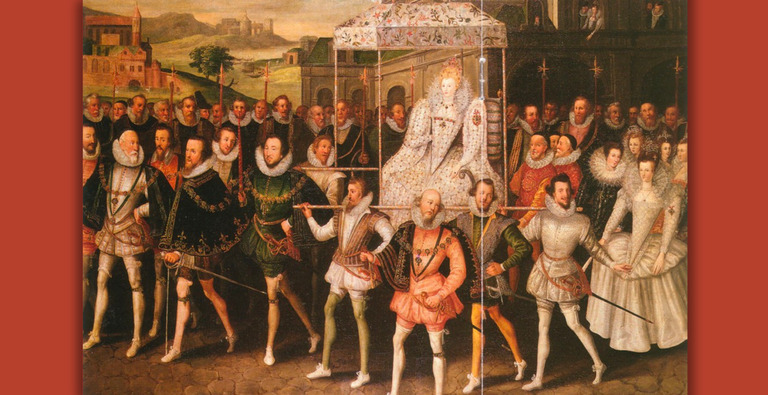

When Elizabeth was notified of Mary’s death, she declared her survival into queendom to be God’s work. This was the great transformation of her life. As queen, she reigned for over forty-four years with great success, and she did it alone. When her reign began, everyone expected Elizabeth to marry so that she might give birth to a son–restoring the masculine line of succession–and have a husband to adopt the crown’s burdens. Yet, Elizabeth, despite her many courtships and flirtations, decided to never marry. James Melville, a Scottish ambassador (1535-1617), told Elizabeth early in her reign, “Your Majesty thinks if you were married, you be but Queen of England, and now you are both King and Queen” (Melville 1683, 46).

When Elizabeth went to Tilbury to support her troops before the invasion of the Spanish Armada, she said, “I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and a king of England too” (Cabala 1663, 37).

Contemporaneous Network(s)

Queen Elizabeth is important to students and scholars of Renaissance history, literature, and women’s studies. She is an icon for girls and women today and plays an important role in popular culture. The Queen Elizabeth I Society, founded in 2002 by Donald Stump and Carole Levin, meets annually with the South Central Renaissance Conference, and the work of the society has also led to many publications by its members.

Contemporary Identifications

To the Protestants of her time, Elizabeth was the Virgin Queen and the Great Protestant Queen. To Catholics, she was a Jezebel.

less

Significance

Works/Agency

When Elizabeth became queen in 1558 it was important to her that she be the queen for the whole nation. As discussed above, her religious settlement was as broadly based as possible. A number of Mary’s members of the Privy Council continued in their roles with the new queen, and she appointed a range of men of different backgrounds over the course of her reign.

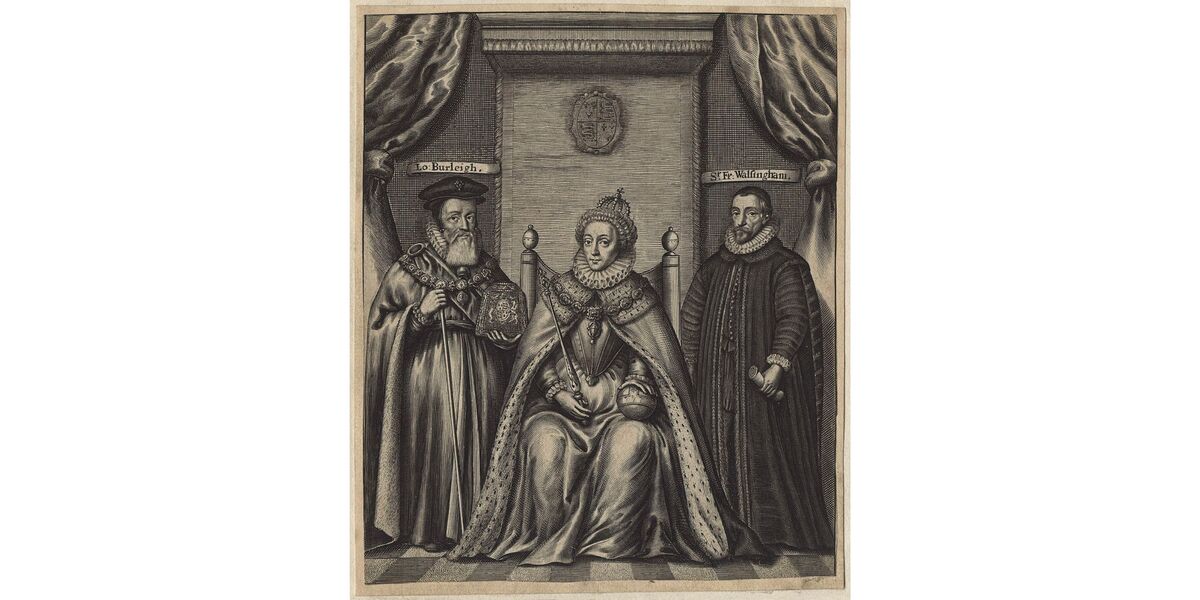

The most important members were William Cecil (1520-1598), who was the Lord Burghley and Principal Secretary and Lord Treasurer to the queen; Sir Francis Walsingham (1532-1590), also the Principal Secretary; Robert Dudley (1532-1588), who was the Earl of Leicester; Sir Christopher Hatton (1540-1591); and Thomas Radcliffe (1525-1583), the Earl of Sussex.

Elizabeth worked hard to keep her country safe and prosperous. She restored the value of English currency, which had been seriously devalued; she standardized measures throughout the kingdom to facilitate internal trade; and she developed trade routes internationally.

In addition to religion, another issue of great significance was the succession. Her Parliament wanted her to marry, and there were many diplomatic negotiations that included a potential marriage. None of these marriage efforts were successful, but the negotiations often produced trade relationships or expressions of friendship. But without a marriage and child, the question of who would rule after Elizabeth became more pressing. Henry VIII’s will stated the descendants of Henry’s younger sister Mary were the heirs, particularly Lady Katherine Grey (1540-1568). But by right of primogeniture, it would be the descendants of Henry’s older sister Margaret Tudor (1489-1541), particularly Mary Stuart, Queen of Scotland. Throughout her reign, Elizabeth refused to name an heir, stating her faith that God would provide an appropriate heir when needed. To make the matter more contentious, some Catholics claimed Elizabeth was born while Henry was still married to Catherine of Aragon, and so she had no right to rule, making the true queen Mary Stuart.

After a first decade of relative peace, conflict began in 1568 when Mary Stuart was forced to abdicate her throne in Scotland after the murder of her second husband Henry Stuart (1545-1567) and the impetuous marriage to James Hepburn (1535-1578), the 4th earl of Bothwell, who many believed was the murderer; Mary was imprisoned. When she managed to escape, she fled Scotland for England. Mary wanted aid from Elizabeth in her restoration as the queen of Scotland, but she also sought help from Spain, promising that if she became queen of England, deposing Elizabeth, she would reinstate mass all over the country. Elizabeth feared returning Mary to Scotland would lead to her death, but she knew if she allowed Mary to go forward to France or Spain, there might be an invasion in an attempt to instate Mary as queen of both Scotland and England. Elizabeth decided to keep Mary under house arrest in England. At first, Mary had many servants and some freedom of movement, but after a series of plots to assassinate Elizabeth, to place Mary on the throne, Mary’s movements were restricted.

After nearly twenty years, the 1586 Anthony Babington conspiracy occurred, and there was clear evidence of Mary’s involvement in the attempt to have Elizabeth assassinated so she could be queen. Though Mary claimed that the queen had no right to do so, she was put on trial, found guilty, and condemned to death. Elizabeth refused to sign the death warrant for some months, but in February of 1587, she signed the order and Mary was executed.

Elizabeth had been supporting Protestants in the Netherlands against Spain, and in 1588, the year after Mary’s execution, Philip II sent his Armada to conquer England in hopes of making his daughter, Isabella, the new queen and restoring England to Catholicism. England defeated the Armada. A high point in her reign, Elizabeth was considered to have divine approval.

Beyond diplomacy and warfare, the end of Elizabeth’s reign was a time of cultural achievement, featuring the works of William Shakespeare, among other writers and artists of the time. These later years were also difficult ones for Elizabeth and England. There were bad harvests, inflation, and conflict in Ireland. One of the Queen’s longstanding soldiers and courtiers, Robert Devereux (1565-1601), the 2nd Earl of Essex, led a failed rebellion in 1601 that resulted in his execution. Two years later, Elizabeth died and there was a smooth transition of power to Mary Stuart’s son, James VI.

Elizabeth gave speeches and wrote many letters; she also composed poetry and prayers and did translations. Some of her earliest prayers were written when she was under house arrest in Woodstock after she had been in the Tower during her sister Mary’s reign, and she signed them “Elizabeth the prisoner” (Elizabeth I 2000, 46). After she recovered from smallpox in 1562, Elizabeth published several prayers. One stated that she wished God to “Create in me a clean heart, O God, which may truly declare Thy mercy and my misery. For Thou art my God and my King; I am Thy handmaid and the work of Thy hands. To Thee therefore I bend the knees of my heart” (Elizabeth I 2000, 136).

As well as her speech at Tilbury, the other famous speech in her lifetime was her extemporaneous Latin speech to the Polish ambassador in 1597. There had been tensions between England and Poland due to King Sigismund III of Poland’s (1566-1632) intense Catholicism and close relationship with Spain and the Holy Roman Empire. Queen Elizabeth and her Council were pleased in July 1597 when they were informed that Sigismund was sending the queen a special ambassador. Elizabeth hoped for better relations, including trade. Elizabeth decided to honor the Polish ambassador Paul de Jaline, or Pawel Dzialynski/Dzialin, by greeting him publicly with great honor. Shocking the queen and all her court, the ambassador instead publicly and loudly insulted her. Sir Thomas Egerton (1540-1617), Viscount Brackley and Lord Chancellor, began to rise to respond, but the queen herself responded in Latin, stating that: “I marvel much at so great and so insolent boldness in open Presence; neither do I believe if your king were present that he himself would deliver such speeches. But if you have been commanded to use suchlike speeches . . .it is hereunto to be attributed: that seeing your king is a young man . . . that he doeth so perfectly know the course of managing affairs of this nature with other princes as his elders have observed with us.” She added that the ambassador showed himself “utterly ignorant what is convenient between kings” (Elizabeth I 2000, 333). Those who witnessed the exchange wrote exultantly at how Elizabeth handled it, and soon it was the buzz of London.

In her final speech to Parliament in 1601, Elizabeth reflected on her reign not just for members of Parliament but for all of the people. She again thought of what it meant to be both king and queen. “To be a king and wear a crown is a thing more glorious to them that see it than it is pleasant to them that bear it. For myself, I was never so much enticed with the glorious name of a king or royal authority of a queen as delighted that God hath made me His instrument to maintain His truth and glory, and to defend this kingdom (as I said) from peril, dishonor, tyranny, and oppression.” She ended her speech by showing what was most important to her as ruler: “Though you have had and may have many princes more mighty and wise sitting in this seat, yet you never had nor shall have any that will be more careful and loving” (Elizabeth I 2000, 340, 341).

Reputation

There has been a great deal of variety in terms of Queen Elizabeth’s reputation. Early Protestant historians greatly praised her while their contemporary Catholic writers described her immorality. Many traditional historians also claimed that the successes of her reign came from her advisors. Even in the twentieth century there were many writers, female as well as male, who focused on her personality in ways that disparaged the queen. In her popular biography of Elizabeth, The First Elizabeth, Carolly Erickson described the queen as mercurial, emotional, and “dangerously unpredictable in her moods” (Erickson 1983, 173). In a book for students that has gone through a number of editions, the author Christopher Haigh called the queen a “seductress,” a “royal tease rather than a royal tart,” and a “bully,” who “ …harassed the weak while deferring to the strong.” He also wrote, “She was bossy, she was something of a fishwife (or fish-virgin)” and acted like a “nagging wife” to her councilors. In her speeches to Parliament, Elizabeth had “the authentic voice of the English nanny. Elizabeth adopted a tone of condescending superiority toward her Parliaments, confident that if she explained things often enough and slowly enough, the little boys would understand” (Haigh 2014, 36, 61).

But much earlier in the twentieth century, Sir John Neale (1890-1975) presented a more positive view of Elizabeth. In The Elizabethan Age, Neale argued, “Elizabethan England should be regarded as a revolutionary age,” due to the queen. “Never before and never again was the Privy Council so efficient. Elizabeth kept it small, balancing extremely able commoners with aristocrats” (Neale 2005, 8, 16). In his 1934 biography, he addressed the fact that Elizabeth never married as a wise political tactic. “It must have been a question with Elizabeth whether a woman ruler could ever do otherwise than err in marriage; whether, in fact, to be a success as a Queen she might not have to be a Virgin Queen” (Neale 2005, 15).

Legacy and Influence

Queen Elizabeth I’s reign held both problematic and positive legacies. For example, when the English explorer Francis Drake (1540-1596) and the English naval commander John Hawkins (1532-1595) brought seized wealth to England, Elizabeth was thrilled. The pair was also instrumental in defending England against Phillip II and the Spanish Armada. Nonetheless, the material aid they provided for Elizabeth was made possible by the system of slave trade he began in England, a disturbing legacy whose ramifications continue today. In addition to allowing the beginning of the slave trade system in England, Elizabeth’s reign oversaw immense cruelty toward Irish people under English control. Elizabeth was afraid the Spanish would interfere, using Ireland as a base to attack England, were she to release the Irish from English control.

But there were also impressive legacies as well. England did not suffer from violent religious civil wars, as many other nations did, in the second half of the sixteenth century. England expanded its international trade and relations with many areas, including the Ottoman Empire and Russia.

The period of her reign has also been known as the Elizabethan Renaissance, for many artists were able to thrive under her reign. These artists included: Nicholas Hilliard and Isaac Oliver, the composers Thomas Tallis and William Byrd, the poets Edmund Spenser and Philip Sidney, translators such as Mary Sidney Herbert, Jane Lumley, and Anne Cooke Bacon, and the dramas of William Shakespeare and his contemporaries. Some of the strong women characters Shakespeare created in his comedies, such as Rosalind in As You Like It and Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing, may well have demonstrated the impact of having Queen Elizabeth ruling England.

I think the most important legacy of Elizabeth is the example she set for generations of girls. Many women have said that as young girls they were so excited to learn about Elizabeth. In her book Elizabeth I: A Feminist Perspective, published in 1988, the comparative literature scholar Susan Bassnett explained why she wanted to write a book about Elizabeth, who “was, in short, a model of an independent woman for a girl growing up in the 1950s, long before the Women’s Movement had announced itself” (Bassnett 1988, 3).

While Queen Elizabeth was important to many girls, she was especially so to me. I read a biography of her when I was about ten years old and truly it transformed my whole life, as I have taught and written about this extraordinary woman and the age in which she lived my entire career.

less

Controversies

Controversy

There are a number of controversies about Queen Elizabeth I, several of which are still discussed today and are highly questionable. The first is whether or not Elizabeth was physically like other women, the second was if she had lovers and illegitimate children, and the third was the argument that the person ruling as Queen Elizabeth was actually a man.

From the time that she became queen, the pressure on her to marry and birth an heir was intense. There was great interest in whether or not she was able to become pregnant. Foreign ambassadors bribed some of the ladies of her chamber for information on her periods, which were apparently irregular and sometimes light. But as the reign progressed there were also questions about how she was not like other women in some ways. The Papal ambassador in France, Antonio Salviati, wrote to the Cardinal of Como in 1578 saying:

"By persons that have some knowledge of the Court of England I am apprised that the said Queen's physicians deem her life in danger. They say that she has hardly ever had the purgations proper to all women, but that instead nature has come to the rescue by establishing an issue in one of her legs, which has never been scant of flow but the Queen has fallen ill, and at present seems to be quite dried up, nor know the physicians how to find a remedy for this mishap" (Calendar of State Papers, Vatican, British History Online).

Unfortunately, Salviati does not identify who these persons were and where they got this information.

Others during her reign argued that Elizabeth was incapable of having intercourse. This was what Mary Stuart wrote in a letter to Elizabeth detailing the gossip she claimed to have heard from Bess of Hardwick (1518-1608), the Countess of Shrewsbury, when Mary was the enforced guest of Bess’s husband. The letter is filled with hostile and slanderous commentary, including “[Bess] says, moreover, that indubitably you are not like other women, and it is folly to advance the notion of your marriage with the Duke, seeing that such a conjugal union would never be consummated” (Zweig 2010, 299; original letter in French in Murdin and Haynes, 558-59). This belief was apparently widespread.

In this vein, strange stories about Elizabeth continued. In Historical and Critical Dictionary, published in the early eighteenth century, the French philosopher Pierre Bayle relayed a comment by Abraham Nicolas Amelot de la Houssaye, a French historian and political critic, who claimed about Elizabeth, “it is certain, she had no Vulva, and the same Reason, which hindered her marrying.” De la Houssaye added that Elizabeth passionately loved the Earl of Essex, “but such was the make of her Body, that she could not be carnally known of any Man without suffering excessive Pains” (Bayle 1735, 760).

These ideas are still prevalent today–and still problematic. Vaginismus, according to the online Oxford English dictionary, is “Painful spasmodic contraction of muscles of the vagina or pelvic floor, occurring in response to attempted vaginal penetration by the penis in sexual intercourse.” Dr. Julia Reeve, the author of The Vaginismus Book: Pain-free Love, states, “I believe that, possibly, the first-ever documented case of vaginismus was Queen Elizabeth I of England,” adding despite this that Elizabeth had a long-time lover, who she does not name, but Reeve questions how much of a lover he actually was. But Reeve’s claims regarding vaginismus in Elizabeth are riddled with errors, and there is little evidence supporting the reality of Queen Elizabeth I’s relationship to sex. Nonetheless, interest in Elizabeth’s body continues to today.

While some were convinced that Elizabeth could not have sexual intercourse, many others were convinced that she had numerous lovers and illegitimate children. The rumors about Elizabeth being pregnant started when she was fifteen with the claims that she had an illicit relationship with Thomas Seymour, who was Lord Admiral, the uncle of Edward VI, and the widower of her final stepmother Katherine Parr. As cited by Elizabeth I: Collected Works, Elizabeth responded with a strong letter to Seymour’s older brother Edward, Duke of Somerset and Lord Protector; “Mater Tyrwhitt and others have told me that there goeth rumors abroad which be greatly both against mine honor and honesty . . . that I am in the Tower and with child by my lord admiral. My lord, these are shameful slanders, for the which . . . I shall most heartily desire your Lordship that I may to come to the court . . . that I may show myself there as I am” (Elizabeth I 2000, 24). But these rumors continued and became more intense once Elizabeth became queen. There were a number of investigations about statements made by Elizabeth’s subjects. To give just a few examples: a Lady Baxter stated in 1563 that Elizabeth looked like a woman who had recently had a child; Robert Marsham stated a few years later that the queen had had two children by Robert Dudley; two children of the queen were also mentioned in 1580; in 1575, there were comments that Elizabeth had a thirteen-year-old daughter;in 1581, Henry Hawkins claimed Elizabeth had five illegitimate children;even more disturbing were Dionisia Deryck and Robert Garner’s statements in the early 1590s, when each claimed that a number of the children born to Elizabeth were then murdered.

The idea that Elizabeth had illegitimate children continued in the centuries after her death and grew to be intertwined with the Shakespeare authorship controversy. In the late nineteenth century, the American physician Orville Ward Owen authored Sir Francis Bacon’s Cipher Story (1893-95), a book that argued not only was Bacon the true author of Shakespeare’s plays but also the secret son of Queen Elizabeth and Robert Dudley.

This theory was also expounded by those who claimed the true author of the plays was Edward de Vere (1550-1604), Earl of Oxford. The journalist Percy Allen (1875-1959) stated that Oxford wrote Shakespeare’s plays and was also Elizabeth’s lover; their son, Allen wrote, was Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton. In Oxford, Son of Elizabeth (2001), Paul Streitz claimed that Oxford was the son of Elizabeth and Thomas Seymour, and that he was the first of her five children. The final child, Southampton, as Allen had also argued, was the son of Elizabeth and Oxford, making him both Elizabeth’s son and grandson. This was dramatized in the 2011 Anonymous. Both the book and the film are riddled with historical errors.

There is no evidence that Elizabeth held any physical differences from other women, nor that she had any lovers or children.

The final controversy–and the most far fetched of all–is the argument that Queen Elizabeth was really a man. The story developed in the Cotswold village of Bisley. Elizabeth’s governess, Katherine Ashley, and her treasurer of the household, Thomas Parry, brought the ten-year-old Elizabeth to Overcourt, a large manor house in the village. While there, the child played with John Neville, a boy of around her age whose family lived nearby. The two resembled each other. Henry VIII was coming to visit, and a few days before he arrived Elizabeth suddenly died. Ashley and Parry were terrified at how the king would respond and tried to find a girl in the village who could be a substitute, but there were none who looked enough like Elizabeth. Instead, they made an arrangement with the Neville family that John would play the role. It worked perfectly and Henry had no idea. Ashley and Parry kept the scheme going. Apparently, the Nevilles were willing to give up the boy because he was not really their son. Rather, John was the illegitimate son of Henry Fitzroy, Henry VIII’s illegitimate son who had died at the age of seventeen in 1536. For the next sixty years no one ever found out the secret, and John ruled as “queen” of England. Apparently, he went undiscovered after his death because he had insisted his body not be examined. In the nineteenth century, during some renovations of Overcourt, a Tudor coffin was found; in it was the skeleton of a young girl with the remnants of what was once a fine Tudor dress. But the coffin was again buried, and no one knows where. A number of authors over the twentieth century–including Bram Stoker of Dracula, Chris Hunt of The Bisley Boy, and Steve Berry of The King’s Deception–used this story in their books to apparently explain Elizabeth’s success, effectively arguing that a woman could not have been a great ruler, and so she must have been a man.

Overall, Queen Elizabeth was a complex and impressive woman. She made mistakes, but she was an effective ruler. In regards to her controversies, there is no evidence supporting any physical limitations or illegitimate children. Indeed, had that been the case, the secret would have been impossible to keep. Concerning the theory that Elizabeth was a man, Elizabeth Tudor did not die at the age of ten but some months before her seventieth birthday.

less

Bibliography

Primary (selected):

Ascham, Roger. “Scholemaster.” The Scholemaster,

www.luminarium.org/renascence-editions/ascham1.htm. Accessed 1 Aug. 2023.

Aske, James, Elizabetha Triumphans. London, 1588.

Bacon, Francis. The Letters and the Life of Francis Bacon. James Spedding, ed. London:

Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts, 1861.

Bayle, Pierre. Mr. Bayle’s Historical and Critical Dictionary, the second edition, revised, collected, and enlarged by Mr Des Maizeaux. London, 1735.

British History Online. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/

Cabala. Mysteries of State and Government: in Letters of Illustrious Persons and Great

Ministers of State. London, 1663.

Camden, William. The History of the Most Renowned and Victorious Princess Elizabeth, Late Queen of England. London, 1688.

Elizabeth I. Collected Works. Leah Marcus, Janel Mueller, and Mary Beth Rose, editors. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000.

Harrison, G. B. The Elizabethan journals: being a record of those things most talked of during the years 1591-1603. Comprising An Elizabethan journal, 1591-4, A second Elizabethan journal, 1595-8, A last Elizabethan journal, 1599-1603. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1955.

Melville, James. The memoires of Sir James Melvil of Hal-hill containing an impartial account of the most remarkable affairs of state during the last age, not mention'd by other historians, more particularly relating to the kingdoms of England and Scotland, under the reigns of Queen Elizabeth, Mary Queen of Scots, and King James: in all which transactions the author was personally and publickly concern. George Scot, editor. London, 1683.

Murdin, William and Samuel Haynes, editors. A collection of state papers, relating to affairs in the reigns of King Henry VIII. King Edward VI. Queen Mary, and Queen Elizabeth, from the year 1542 to 1570. London, 1740-1759.

Speed, John. The history of Great Britaine under the conquests of ye Romans, Saxons, Danes and Normans. London, 1611.

State Papers Online, 1509-1714. https://www.gale.com/primary-sources/state-papers-online

Secondary (selected):

Bassnett, Susan. Elizabeth I: A Feminist Perspective. Oxford: Berg, 1988).

Doran, Susan. Elizabeth I & Her Circle. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Erickson, Carolly. The First Elizabeth. New York: Summit Books, 1983.

Green, Janet M. "Queen Elizabeth I’s Latin Reply to the Polish Ambassador." The Sixteenth Century Journal 31, 4 (2000): 987-1008.

Haigh, Christopher. Elizabeth I. 3rd edn. London: Routledge, 2014.

Levin, Carole. The Heart and Stomach of a King: Elizabeth I and the Politics of Sex and Power

2nd ed. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013.

Levin, Carole. The Reign and Life of Queen Elizabeth I: Politics, Culture, and Society. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2022.

Neale, J. E. Queen Elizabeth I. Chicago: Chicago Review Press; Reprint edition, 2005.

Paranque, Estelle. Elizabeth I Through Valois Eyes: Power, Representation, and Diplomacy in the Reign of the Queen, 1558-1588. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

Riehl, Anna. The Face of Queenship: Early Modern Representations of Elizabeth I. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Stump, Donald. Spenser’s Heavenly Elizabeth: Providential History in the Faerie Queene. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

Zweig, Stefan, et al. Mary, Queen of Scotland and the Isles. Ishi Press International, 2010.

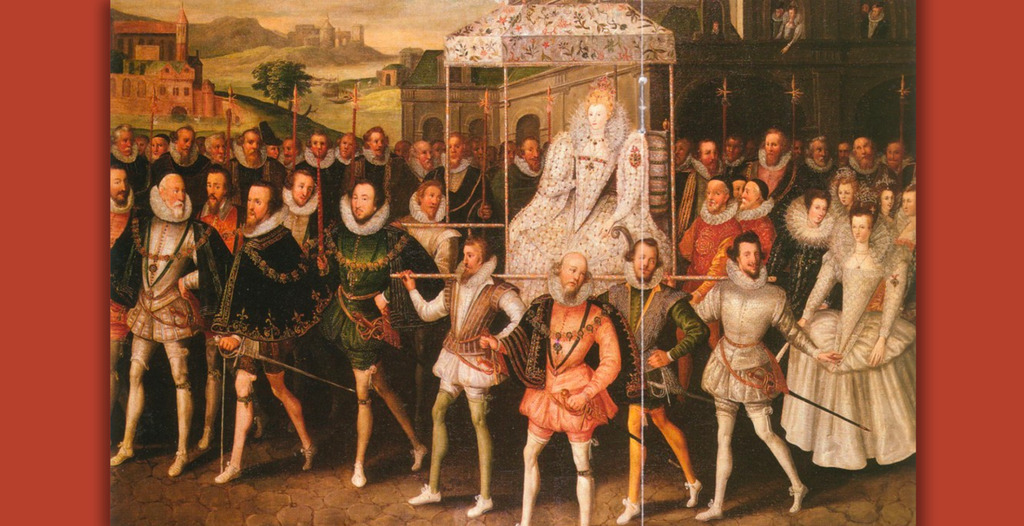

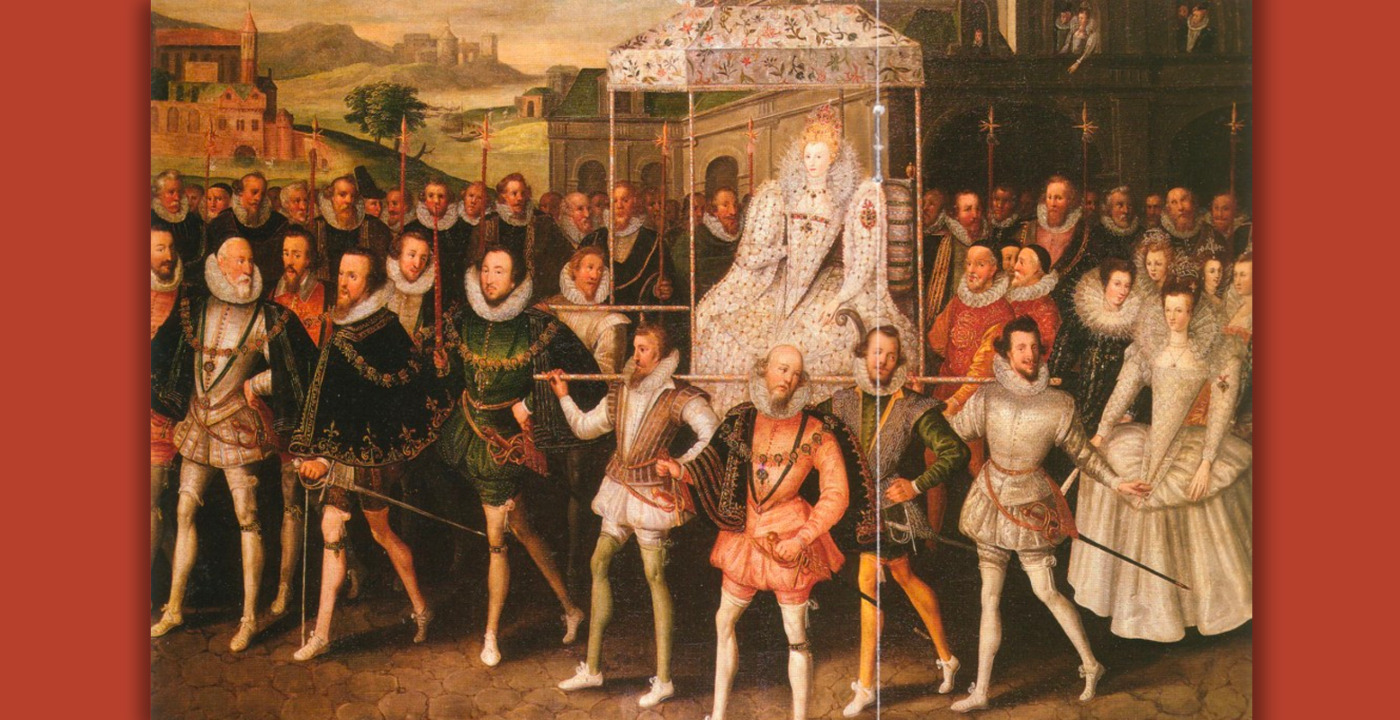

Images:

There are many portraits of Elizabeth. Some very fine ones are at the National Portrait Gallery and at Hatfield House.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully