Birth

April 23rd, 1858 in India

Death

April 5th, 1922 in India

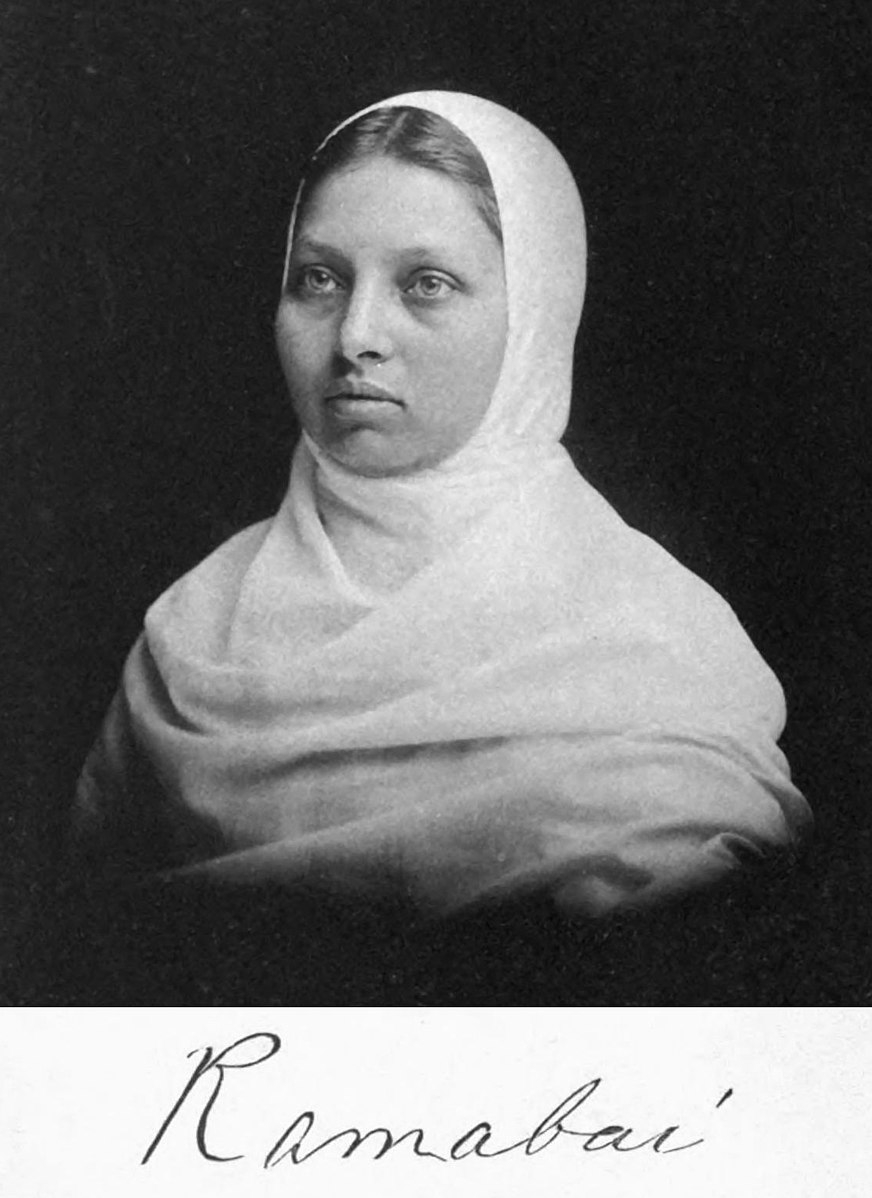

Ramabai Dongre, popularly known as Pandita Ramabai Saraswati, was a pioneering figure in Indian social reform, education, and women's rights. Her life was marked by an extraordinary journey of intellectual achievements, social activism, and personal resilience, making her one of the most influential figures in 19th and early 20th-century India. Known for her intellectual prowess and knowledge of Sanskrit, she became one of the first women to receive the title of Pandita, learned woman, and Saraswati, goddesses of wisdom. Her enormous contribution to women’s education, rehabilitation of destitute women, advocacy for women’s emancipation, and many other endeavors positions her as an important feminist foremother of modern India. Her writings and works heralded the first wave of feminism in Modern India and proposed a strong critique of religion, patriarchy, and colonialism, including her seminal work The High Caste Hindu Women (1887).

Personal Information

Name(s)

Born as Ramabai Dongre, she later came to be known as Pandita Ramabai Saraswati after receiving the titles ‘Pandita’ and ‘Saraswati’ after a panel of Sanskrit scholars consisting of Professor Charles Henry Tawney, Professor Archibald Gough, and Pandit Maheshchandra Nyayaratna publicly examined her and bestowed her with these titles in 1878.

On 29 September 1883, Ramabai converted to Christianity and was given the name Pandita Mary Ramabai; however, she chose to be known by her initial name, Pandita Ramabai Saraswati.

Date and place of birth

April 23, 1858, Gangamul, Mangalore, India

Death and place of death

April 5, 1922, Kedgaon, Bombay Presidency, India

Family

Mother: Lakshmibai (Born: 1827 (approx.) Died: 1874

Father: Anant Shastri Dongre (Born: 1795-6 (approx.) Died: 1874

Marriage and Family Life

Spouse: Bipin Behari Medhvi (Husband)

Children: Manorama (Daughter)

Siblings: Srinivas (Brother) and Krishnabai (Elder Sister)

Education (Short Version)

Homeschooled by her parents, she later studied at Cheltenham Ladies’ College, where she studied Natural Science, Mathematics, and English.

Education (Long Version)

During her childhood, Ramabai was not formally educated. However, her parents, Ananth Shastri Dongre and Lakshmibai trained her in Shastras, Puranas, and Sanskrit at home. Providing education to the girl-child was considered unusual and heretical by the community to which Ramabai belonged. It was due to her progressive father, who was a learned Brahmin, that Ramabai had an unconventional childhood, during which she received an education and did not have to marry as a child.

Later, during her stay in Wantage, England, she attended Cheltenham Ladies College, where she studied Natural Science, Mathematics, and English.

Religion

Born into a Hindu Family, she and her family practiced many paths within Hinduism. Initially, they were devout followers of the Advaita doctrine. Later, they shifted to the Bhakti faith and eventually became Vaishnavites. She later accepted non-denominational Christianity.

Transformation(s)

Ramabai Saraswati, in ‘Testimony,’ refers to herself ‘as the daughter of the jungle’ because of her childhood and early adulthood. She had a tough life from the beginning. She was born in Gangumal Forest and did not grow up like other girls. During the years in the forest with her progressive parents, who suffered and were ostracized for living against the orthodox order, her father, Ananthshastri Dongre, was significant in raising her in an unorthodox manner, which manifested in her work, her contributions, and her actions. She learned from him the virtue of freedom and equality. However challenging the path of righteousness was, she had nothing to fear except the one true God. Ramabai’s life was filled with grief and sorrow. She was raised in a family that suffered from economic scarcity (as they had to survive on the alms they received). She lost both her parents at the age of sixteen, saw the plight and death of her elder sister Krishnabai, and eventually lost her brother Srinivas. In 1882, she lost her husband to cholera. At twenty-four, Ramabai was a widow with a ten-month-old child to take care of. All these personal losses were significant in transforming and shaping her as an advocate and reformer for the rights of women, especially for widows. Ramabai worked against all the odds and pursued emancipation for fellow country women who suffered from similar oppression due to centuries-long regressive customs against widows. Perhaps these untimely losses of family members due to illness provoked Ramabai to seek a career in medicine.

Many transformational events marked Ramabai's life. Her meeting with the Brahmo Samaj leader, Keshab Chandra Sen, was significant because it encouraged her to widen her understanding of the religious scriptures and read the Vedas, which she was initially reluctant to read, as the customs discouraged and forbade women from reading the Vedas. The status of women in Hinduism and their dependent position at every stage of life was prescribed in these scriptures. Ramabai overcame her fears and anxieties and engaged critically with the scriptures. She started lecturing on the differential treatment of men and women in Hindu scriptures and the pernicious restrictions on women from availing individual liberty. The endowment of the titles Pandita and Saraswati came after the detailed examination of her knowledge and understanding of the scriptures in 1878. This is akin to the contemporary title of Doctorate.

Her establishment of Arya Mahila Samaj–an organisation to promote education, rights, and healthcare for women, with pronounced emphasis on widows and child widows–in 1882 was significant. Her travels to England in 1883 and later to the USA in 1886 were also transformative for the time, as women were forbidden from traveling overseas according to the Hindu scriptures.

Her establishment of Sharda Sadan and Mukti Sadan, residential schools for widows and Destitute women, was radical and subversive, as these were the first schools established by a woman.

Contemporaneous Network(s)

Ramabai became associated with many associations, such as Prarthna Samaj, Brahmo Samaj, Arya Mahila Samaj, Community of Saint Mary the Virgin, National Women’s Suffrage Association, and Ramabai Association.

She also established: Sharda Sadan, Mukti Sadan, Kripa Sadan.

less

Significance

Works/Agency

- Lamentation of the Divine Language/ A Sanskrit Ode (1881)

- Stri Dharma Niti (1882)

- Englandcha Pravas (1883)

- The Cry of Indian Women (1883)

- The High Caste Hindu Women (1887)

- United Stateschi Lokasthiti ani Pravasavritta (People of the United States) (1889)

- Famine Experience (1897)

- A Testimony of Our Inexhaustible Treasure (1907)

Reputation

In her early adult life, Ramabai gained fame and reputation because of her knowledge of Sanskrit and her oratory skills. She was well known within the reformist circles, whether the Brahmo Samaj of Bengal or Prarthana Samaj of Maharashtra. Her progressive views and her critical attitude towards the rigorous orthodox and patriarchal practices within Hindu communities, especially those belonging to the upper caste, also were a focal point of attention for the conservative and revivalist Hindu organizations and thinkers. As one of the first women to be accorded the Saraswati and Pandita titles, she was widely covered by various newspapers and magazines.

The English colonial state was also aware of Ramabai’s organizational work and contribution. In fact, she was one of the women who deposed/testified in front of the Hunter Commission (established to investigate Education in India) in 1882. She gave some very serious recommendations to them. Eventually, she was conferred with the Kaisar-I-Hind Medal for community service in 1919.

Legacy and Influence

Invoked as one of the feminist foremothers of Modern India, Ramabai through her life, actions, and contributions, helped create the nascent feminist consciousness. Several women leaders referred to her as an inspiration and exemplar in their individual and organizational pursuits of an egalitarian India.

Her celebrated work The High Caste Hindu Women is considered a canonical text in the field of feminist literature in India and is considered ‘the feminist manifesto’ of the country.

Ramabai's association, established in 1889, continues to exist and contribute to the cause of women’s rights. It is now renamed The Pandita Ramabai Mukti Mission and has carried Ramabai’s legacy for 130 years. Ramabai’s contribution to women’s education was also significant; she was one of the first people to introduce Froebel’s teaching method in India. Arya Mahila Samaj, founded by Ramabai, continues to function and contribute, as it runs several hostels and programs for girls.

less

Context

On April 23, 1858, in Gangamul, Ramabai was born to a progressive family. Her father was Ananthshastri Dongre, a learned Sanskrit scholar, and her mother was Lakshmi Bai. Pandita Ramabai spent her early years under the educational training of her father, who was different from the many conservative men who believed that women should be educated only in Sanskrit and religious texts. Her father drew inspiration from Bajirao II, Peshwa–the chief minister among the Maratha people of India–who had taken the services of Ananthshatsri to teach his wife, Varanasi Bai, against the established customs and traditions of the times, which denied education to women. Consequently, Ananthshastri, too, decided to teach and train his wife, Laksmi, and daughter, Ramabai.

Ananthshastri was ostracized and forced to leave his ancestral home at Mal Heranji near Mangalore in Southern Karnataka as a result of his decision to educate his wife and daughter. He went to Gangamul forest to establish his ashram when Ramabai was six years old. Ramabai spent her early childhood in the forest, which was home to her for many years. She referred to herself as ‘Being [a] Daughter of the Forest’ to signify her indomitable spirit.

The first phase of Ramabai’s life was full of personal tragedies, with the loss of her immediate family: her parents, sister, and brother, and later her husband, who died within two years of their marriage. At the age of sixteen, Ramabai was orphaned; both her parents died from the suffering caused by penury and ill health. Stringent ritualism led to extraordinary expenses for and trauma to the family. Left with the responsibility of her young brother, who traveled with her on lecture tours, life was challenging for her. Then he too passed away in 1880 from cholera.

However, these losses were formative in shaping Ramabai. They provided her with the opportunity of an unconventional life, whereby she received an education and, as a Puranik, traveled around the country for her lecture tours. Her travels throughout India widened her ambition. Ramabai called herself ‘the daughter of the Jungle,’ for she was raised in the Jungle and lived independently from the rigorous and often regressive customs of Hindu Orthodoxy.

Ramabai married Bipin Behari Das Medhavi, a lawyer from the Bengali Brahmo community in November 1880. Unfortunately, Medhavi passed away in 1882, leaving the twenty-four-year-old Ramabai to care for their infant daughter.

As a young widow, Ramabai was invited by M.G. Ranade, founder of Prarthana Samaj and the reformist elite of Maharashtra, to move to Maharashtra, her native state; with their support, she established the Arya Mahila Samaj, an organization dedicated to women's welfare, in 1882. After arriving in Pune, she also came in contact with various Christian organizations, where she met Reverend Nehemiah Goreh (Nilkanth-Shastri Gore), a former Chitpavan Brahmin who had converted to Christianity in 1848. Goreh left a profound impact on her religious beliefs. Shortly after, she met Sister Eleanor and Sister Geraldine of the Anglican Community of St Mary the Virgin (CSMV). As a widow who suffered many losses, Ramabai had seen the redundancy of practices that were prevalent in Hindu orthodoxy. She critiques how they prevailed at the cost of Hindu Women and continued to persist in complementing the patriarchy. The general apathy towards widows in Hindu Society was glaring at the time, and they were subjected to inhumane conditions. Ramabai’s subtle criticism of the patriarchy in Hindu society can be observed in her work Stri Dharma Niti (1882).

With the help of the Community of St. Mary the Virgin (CSMV), Ramabai traveled to England to pursue her dream of studying medicine. In England, she stayed at the Community of St. Mary the Virgin, at Wantage. However, she could not pursue a medical career because of her own poor health. Her years in England were transformative, as she eventually enrolled in Cheltenham Ladies College to study Natural Science, Mathematics, and English. She was later offered a professorship to teach Indian languages by the principal, Dorothea Beale. Estranged from her previous faith and in search of a new guiding force that could provide her solace, she converted to Christianity. Ramabai’s inquisitive tendencies, non-conformist nature, and pursuit of truth sometimes positioned her in an antithetical position with the Anglican Church and Sister Geraldine, in particular. There were often over-arching disagreements about the nature of Christian faith and authority; in addition, the Anglican Church’s patriarchal attitude to Ramabai was filled with colonial arrogance and racial contempt.

In 1886, Ramabai received an invitation from Dr. Rachel Bodley, Dean of the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania, to attend the graduation ceremony of Anandibai Joshee in March 1886, who was to become India's first woman doctor. Ramabai accepted the invitation against the wishes of CSMV. After spending nearly three years in England, she left for the USA in March 1886. America opened a new world for Ramabai and her pursuit of education and support for widows. In 1887, Ramabai wrote her much-celebrated work, The High Caste Hindu Women, as a plea to raise funds for the residential school she wanted to establish. With the help of her American friends, the American Ramabai Association and Ramabai circles were established to raise funds for her cause, and she found success. In 1889, after returning to India, Ramabai founded Sharda Sadan, a non-sectarian residential school for child widows. The school provided education, skills, and shelter to the widows who lived on the periphery of Indian society. Later, in 1898, Mukti Sadan, another residential school, was established primarily for destitute women and children at Kedgaon, Maharashtra.

Pandita Ramabai Saraswati's many contributions in providing respectful alternatives for widows and destitute women were significant in challenging the patriarchal orthodoxy of her time in Indian society and crucial for heralding gender equality in Colonial India. In 1919, she was conferred with the ‘Kaisar-I-Hind’ Medal for her community service by the British Colonial Government of India. Her legacy is also honored within the Church of England, commemorating her on April 30. Furthermore, on October 26, 1989, the Government of India recognized her significant contributions to empowering Indian women by issuing a commemorative stamp.

less

Controversies

There are several controversies associated with Ramabai. Some pertain to her personal choices and beliefs, and some are, in part, manufactured by her adversaries.

One of the most widely debated and circulated controversies is the choice of her conversion. Her conversion to Christianity was attacked by the conservative leaders of Maharashtra, like Bal Gangadhar Tilak. Her establishment of Sharda Sadan and Mukti Sadan were also publicized in numerous newspapers and journals as proselytizing ventures. In her testimony, Ramabai clearly underlined that her conversion was a personal and spiritual choice and did not, in any way, impact the secular nature of the residential schools. However, she still suffered public humiliation. Tilak's foremost role in defaming and scandalizing Ramabai’s emancipatory ventures was a public outcry and debates. The conservative and orthodox sections often accused Ramabai of proselytizing young widow girls in the name of their rehabilitation. Although Ramabai never overtly engaged in trying to alter the beliefs of the residents of Sharda Sadan, she was not hesitant in criticizing the orthodoxy for their ignorant and alien behavior towards widows and women. Mukti Sadan was an open Christian establishment that worked to shelter destitute women and spread the gospel.

There was a second controversy surrounding the death of Anandibai Bhagat, who accompanied Ramabai on her journey to Wantage, England. Some, like Max Muller, suggested Anandibai committed suicide out of fear of forceful conversion to Christianity, as Ramabai herself had converted. During that same time period, Sister Geraldine accused Ramabai of her negligence towards her fellow companion's emotional status.;The third controversy was at the Cheltenham Ladies’ College, where Ramabai was prevented from giving lectures to male students, which she strongly opposed. This eventually forced her to leave England.

less

Clusters & Search Terms

Current Identification(s)

History; Politics; Gendered Intellectual History; social reform

Clusters

Ramabai has been associated with many organizations that worked for social reform in India and abroad, and she was also associated with organizations concerned with women's empowerment. Some of the organizations in which Ramabai participated were Prarthna Samaj and Brahmo Samaj, with several other contemporary and influential social activists like M.G. Ranade and Keshav Chandra Sen, N.C.Kelkar, R.G.Bhandarkar, etc. She Founded Arya Mahila Samaj (Arya Women’s Association) on June 1, 1882 with four aims: to stop child marriage, to prevent men from taking multiple wives, to rehabilitate destitute women, and to promote female education. Ramabai joined the Community of Saint Mary the Virgin, where she found the company of many women who shaped her future journey; some of them are Miss Anne Hurdford, Sister Geraldine, and Dorothea Beale. During her stay in America, Ramabai came in close contact with the suffragist movement and the Women’s National Temperance Union. Ramabai formed a strong network with feminist circles in the USA. In 1888, she participated in and presented a paper at a conference by the International Council of Women, organized by the National Women’s Suffrage Association. Ramabai’s dedication to uplifting Indian women gained her support from people like Judith Andrews, Dr. Rachel Bodley, and Clementia Butler. With their collective effort, the Ramabai Association saw the light of the day.

Search Terms

Women Emancipation, widowhood, Indian Feminism, Hunter commission 1882, Sharda Sadan, Mukti Sadan, Christianity in India, American Ramabai Association

less

Bibliography

Sources

Pandita Ramabai. Stri-Pharma niti (Prescribed laws and duties on the proper conduct of women), (Kedgaon, Mukti Mission Press, third. ed., 1967), lst.ed., 1882

Bapat, Ram. ‘Pandita Ramabai: Faith and Reason in the Shadow of the East and West’ in Vasudha Dalmia and H. von Stietencron, eds.

Chakravarti, U. (2014). Rewriting history: The life and times of Pandita Ramabai. Zubaan.

Kosambi, M. (2016). Pandita Ramabai: Life and landmark writings. Routledge.

Ramabai, P. (1977). The Letters and Correspondence of Pandita Ramabai, edited by A. B Shah. Bombay: Maharashtra State Board for Literature and Culture.

Sarasvati, R., & Ramabai, P. (2003). Pandita Ramabai's American Encounter: The Peoples of the United States (1889). Indiana University Press.

MacNicol, N., Pandita Ramabai. (Calcutta, Association Press, 1926).

Comment

Your message was sent successfully