Birth

Montauban, Huguenot city in the South West of France.

Education

Ursulines school at Montauban.

Death

November 3rd, 1793 in Paris, FranceReligion

Catholic, VariableOlympe de Gouges was a French playwright and political thinker during the French Revolution. She wrote a total of 144 pieces of writing, including plays, tracts, placards, articles, novels, prefaces, and other isolated works. Her most famous work is The Declaration of the Rights of Woman (1791), which was written in response to the preamble to the French constitution, The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789). She is now honored as one of the first proponents of feminism in France, but her work is still mostly unknown.

Personal Information

Names

Marie Gouze (birth), Veuve Aubry (married), Olympe de Gouges, Marie-Olympe de Gouges (assumed).

Date and place of birth

Born 7 May 1748 in Montauban, Huguenot city in the South West of France.

Date and place of death

Guillotined on 3 November 1793, Paris.

Family

Mother: Anne-Olympe Mouisset (1714–?)

Birth father: Jean-Jacques Le Franc de Pompignan (1709–1784)

Official father: Pierre Gouze (1716–1750)

Anne-Olympe was the daughter of Anne Marty, of whom nothing is known, and a wealthy and respected solicitor and textile merchant, Jacques Mouisset. Jean-Jacques Le Franc de Pompignan was the son of a local high magistrate, heir to the castle of Pompignan, and godfather to Anne-Olympe. Jacques Mouisset was Jean-Jacques’s tutor. When Anne-Olympe was born, the Le Franc Pompignans asked Anne Marty to nurse their younger son, Jean-Georges. The latter inherited a high position in the church, and when Jean-Jacques died, he failed to act on a verbal promise to support Anne-Olympe financially. It is thought that Anne-Olympe died in sickness and poverty, with only her youngest daughter, Gouges, to support her.

Anne-Olympe and Jean-Jacques grew up together and developed a close relationship so that Jean-Jacques had to be sent away by his family, who wished to avoid a marriage with a respectable but non-aristocratic family. Anne-Olympe married Pierre Gouze, a butcher, in 1737. Gouze was sent travelling in 1747, and a year later, on the day of his return, his daughter, Marie, was born. Gouze’s journey coincided with the return to Montauban of Anne-Olympe’s lover, Jean-Jacques. Though there is no real proof that Le Franc de Pompignan, rather than Gouzes, was her father—the birth registry names Gouze, but it could had been added after 1789, when records of illegitimate births were ‘corrected’—the resemblance between Gouges and Le Franc Pompignan was striking enough that Paris society accepted that she was indeed his illegitimate daughter.

Marriage and Family Life

Marie Gouze was married to Louis-Yves Aubry, intendant in charge of food for the comte Alexis de Gourgues, in 1765. In her autobiographical novel, she states that she was married at 14, against her will, to a man she found rude, unpleasant, and beneath her, and that another party she much preferred was inexplicably rejected by her mother.

In August 1766, her son Pierre Aubry (1766–1803) was born. Louis-Yves died in November, possibly by drowning in the river Tarn, which inundated Montauban that year, or from one of the many diseases caused by the inundation.

The young widow, refusing to use her husband’s name, became Olympe (later Marie-Olympe) de Gouges. Olympe was her mother’s name, given to her by her godmother Anne-Olympe Colomb de la Pomarède. Gouges was a possible spelling of Gouze (Occitan was a spoken language more than a written one, so that many words had alternative spellings), and ‘de’ a common way of saying ‘daughter of’. Several political tracts of 1792 are signed ‘Marie-Olympe de Gouges’. For legal papers she signed ‘Marie Gouze, Veuve Aubry’. In other texts she refers to herself as ‘Olympe de Gouges’.

In 1767, Olympe met Jacques Biétrix de Rozières, a military man who became her lover. She refused to marry him, preferring to remain single. They remained close until the year of her death.

Circa 1769, Olympe gave birth to a daughter, Julie (at least that is how she is named in the autobiographical play, Madame de Circey), who died in childhood or infancy. The only (nonfictional) record of her existence arose during Gouges’s trial, where she claimed that she knew she was pregnant as she could recognise the symptoms that she was expecting from her first two pregnancies.

Education

Gouges was educated in a day school. The Ursulines school at Montauban had been started in 1682, by six Ursuline sisters from Toulouse. The school was run by women who had taken religious vows, and offered free classes to local girls in basic reading and writing, religious education, and sewing. The point of such an education was to prepare girls to become good Catholic housewives. In the autobiographical novel Memoires de Madame de Valmont, she relates that her birth father had offered to take over her education but that her mother had refused. Gouges seems not to bear a grudge and to enjoy being able to describe herself as a natural genius, who owes all her wisdom to nature herself. As a result of her neglected education, however, she did have trouble holding a pen, and hired secretaries to take down dictation for all her works. This, and perhaps the fact that she would have had a thick southern accent at the beginning of her time in Paris society, earned her the reputation of illiteracy.

Religion

Olympe was educated in a Catholic school but grew up in a Huguenot town, so that her religious experiences as a child may have been mixed. In her writings, she refers to God and nature sometimes interchangeably, and trusts in the goodness of both. Following God, or nature, ensures that we too will be good, and happy. Her religion does not seem to admit to differences in status between men and women. She does believe in the sanctity of union between men and women, and of the family, but such unions can only be successful, she claims, if divorce is possible, as otherwise marriage is a form of enslavement, or a tomb. She also claimed equal rights for children born out of wedlock.

Transformation(s)

Before she could become the famous playwright and influential political thinker, Olympe de Gouges had to undergo a number of transformations:

First, she had to master the French language, both spoken and written. As a child, she had spoken Occitan, and perhaps a heavily accented regional version of French. In order to move in the Paris salons, where she frequented aristocrats, she had to transform the way she spoke. To become a writer, she needed to improve her penmanship. Rather than wait until she was fully comfortable holding a quill, Gouges hired the services of a secretary.

She came to Paris with few skills, and, reputedly, great beauty, so that she might easily have become a courtesan. Instead, she became a playwright. She was introduced to the salon of Madame Montesson, who, together with her friend the Chevalier Saint George, ran a home theatre. Later Gouges started her own amateur troupe, in which she acted with her son, Pierre. She started to write plays in 1784, but ran afoul of theatrical politics, and only one of her plays, Zamore and Mirza, was ever performed in Paris, five years after it was submitted, and just for three nights. Gouges ensured that her plays were known by publishing them at her own expense.

On the eve of the revolution, Gouges underwent a third transformation, brought on by witnessing the abject misery of the starving Parisians. In 1788 she wrote her first political tract asking the people of France to start a voluntary tax fund to ease the national debt and to feed the people. Her proposal was printed on the front page of a national newspaper, and a few months later 11 French women from an artistic milieu, led by the artist Adelaide-Marie-Castellas Moitte, donated their jewels to the National Assembly. Two collection points were set up shortly afterward. The first was set up by Madame Pajou, daughter of a sculptor who joined efforts with Madame Moitte to collect more jewels in the aftermath of the first donation. The second was the initiative of Madame Rigal, a goldsmith, who spoke to a gathering of women artists and goldsmiths asking all women of France to follow the example of the 11 women from Versailles and help relieve the national debt.

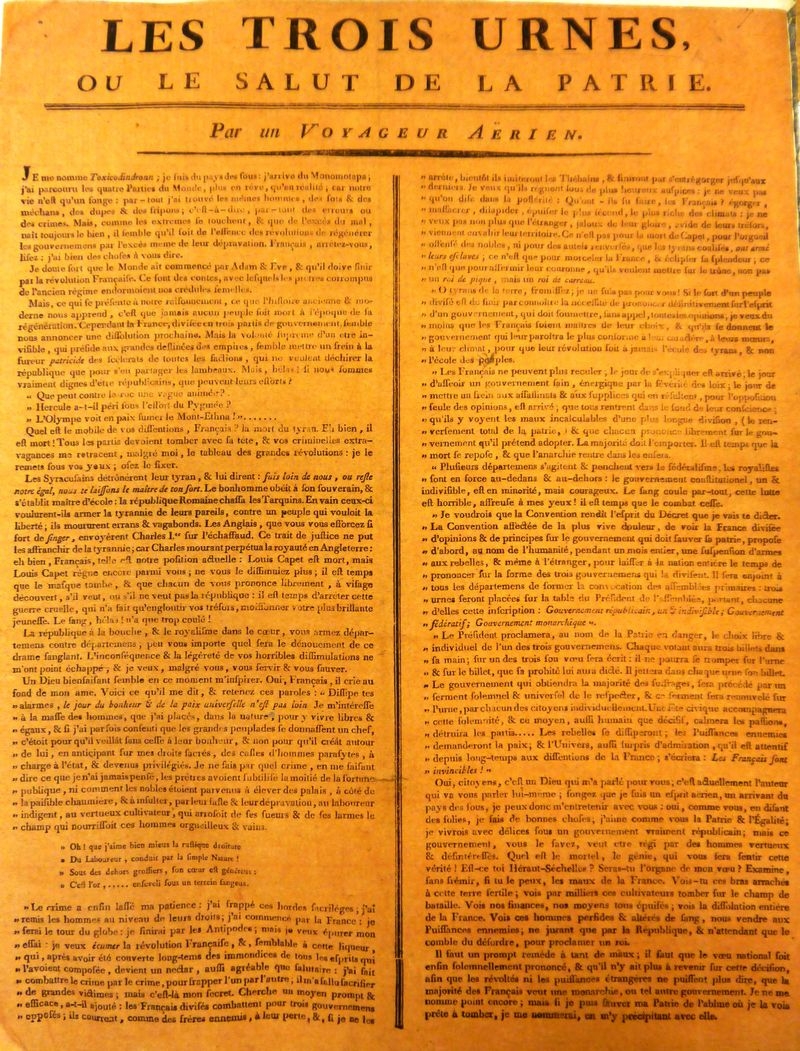

Gouges’s political writing activity increased, and during the revolution, there were many placards by her, sometimes anonymous, sometimes signed, pasted around Paris. Her writings were often critical of the decisions of particular individuals in the government, including Robespierre. Her last track, “The Three Urns”, advocating that the Paris Commune relinquish some of their power and put their motions to the vote through the whole of France, caused her to be arrested and put to death.

less

Significance

Works/Agency

Gouges’s biographer listed 144 pieces of writing by her, including 43 plays; 68 tracts, placards or articles; and 31 novels, prefaces, or isolated pieces. All were written between 1784 and 1793.

Notable works on Gouges are:

Blanc, Olivier. Olympe de Gouges, Des Droits de la Femme à la Guillotine. Paris, Tallandier, 2014.

Scott, Joan. Only Paradoxes to Offer: French Feminists and the Rights of Man. Harvard University Press, 1997.

Women’s Rights and the French Revolution: A Biography of Olympe de Gouges, by Sophie Mousset. Translated from the French by Joy Poirel. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers, 2007.

Sherman, Carol L. Reading Olympe de Gouges. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, 2013.

In 2013, graphic artist Cathy Muller (Catel) drew a biography of Olympe de Gouges, inspired by Blanc’s book and her and writer Bocquet’s research. This is one of the most illuminating works on Gouges’s life.

Catel, and José-Louis Bocquet. Olympe de Gouges. Bruxelles, Paris: Casterman, 2013.

Contemporaneous Identifications

Reputation

During her lifetime Gouges’s works were received in varied ways. She was much praised (in particular by Mirabeau) for her early political works. Her plays were calumniated, first by Beaumarchais, who claimed that her Unexpected Marriage of Cherubino, which she sent him in the hope of patronage, plagiarised his own Figaro, then by Fleury, an actor of the French Theatre, who claimed she had no real talent and stole her ideas from others. She also acquired a reputation as an illiterate, which she reported in “Le Bon Sens Francais”, having overheard a conversation in which a man who claimed to know her said that she only repeated what she was taught, pretending then to dictate it, but could neither think nor write.

After her death, her reputation took another blow. Jules Michelet, in his history of the women of the revolution, refers to her as completely illiterate and carried away by her emotions. At the beginning of the 20th century, a medical student, Alfred Guillois, wrote his doctoral dissertation on Gouges, arguing that she was a prime example of female hysteria in times of political crisis and that she suffered from paranoia reformatoria. Guillois also perpetuated the rumour, started by the actor Fleury, that Gouges had only started writing because she had lost her looks and could no longer attract attention through them, and that she had lost her looks because she had ‘abused them’.

Although she remained known as a victim of the guillotine, and the author of the Declaration of the Rights of Woman, Gouges was more or less shelved as an amusing but ultimately unimportant detail of the French Revolution until the bicentenary prompted more research by French scholars into the works of women during the revolution. Olivier Blanc, in his biography, sought to reinstate Gouges as a significant political thinker and activist, against what he described as Revisionist sexist historiographers, and the thoughtless repetition of their misleading claims by writers of dictionaries and encyclopaedias who perpetuated the myth of Gouges’s illiteracy and lack of influence.

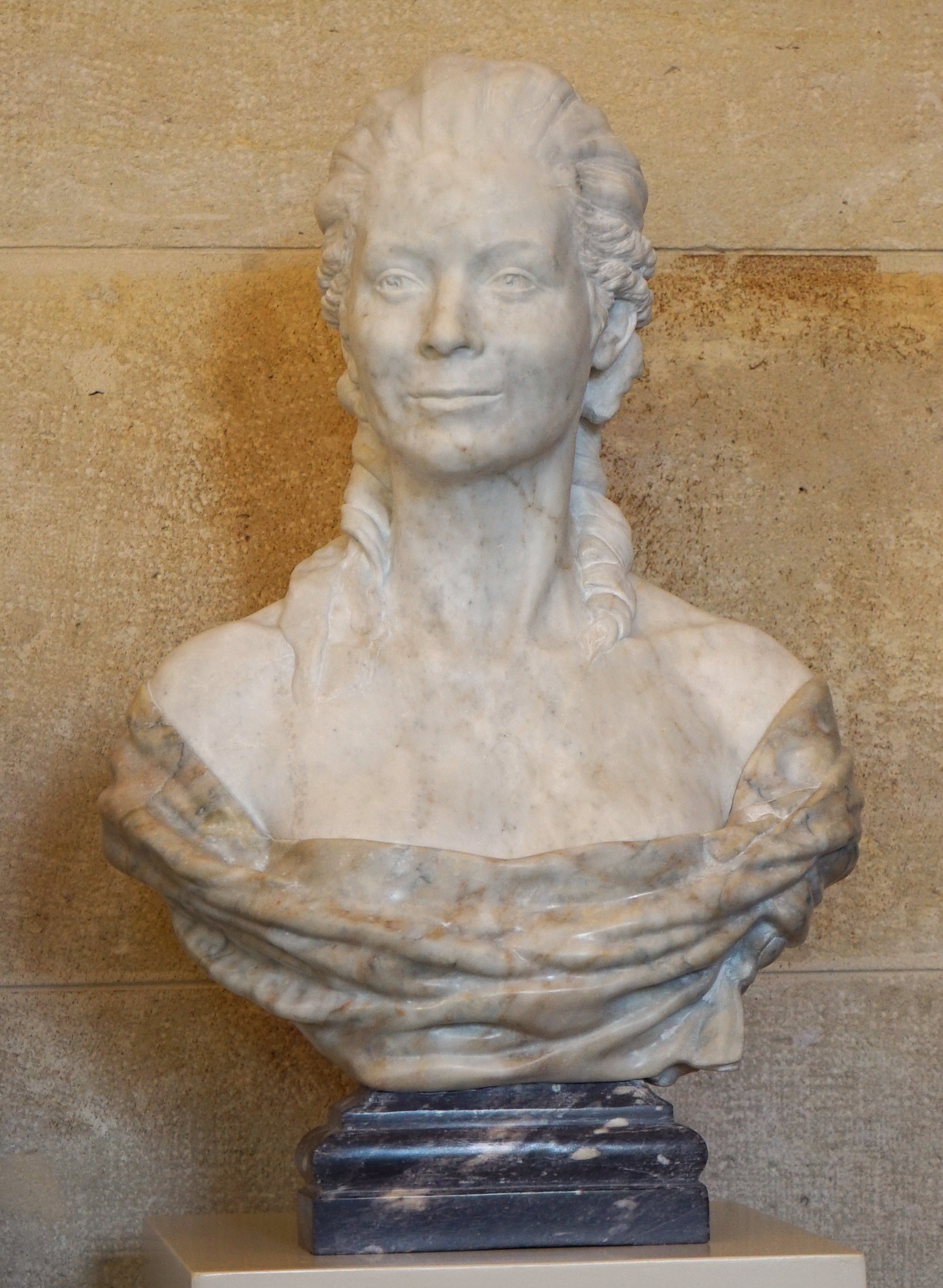

Gouges’s remains have yet to be transferred to the mausoleum of the Pantheon in Paris, having been a candidate since 2014. But her bust was placed at the National Assembly in 2016. She was the first woman to be represented there.

Legacy and Influence

Several French public buildings and streets have been named after Olympe de Gouges, including the Place Olympe de Gouges in the 3rd Arrondissement in Paris, a gynaecological and maternity health centre in Tours, and a theatre in her native Montauban.

In 2014, Gouges was brought to the political limelight again when French historian Eliane Viennot addressed the National Assembly on the need to reform language. Viennot argued that the call to reform the French language to include women as equals dates back to the Revolution, and in particular to Gouges’s Declaration of the Rights of Woman, which was a direct challenge to the failure to include women in the new Constitution. Viennot has been involved in the controversy over ‘inclusive writing’ or the move to reform the grammatical law which claims that the masculine is always stronger than the feminine, and in that work too, Viennot claims the influence of Gouges.

less

Controversies

Controversy

Olympe de Gouges is considered by many the first person to argue for women’s political rights in France, with her Rights of Woman in 1791. Condorcet in fact came first, with his plea for the inclusion of women in rights of citizenship in 1790. It is worth noting that Gouges, Condorcet, and the philosopher Sophie de Grouchy (Condorcet’s wife, who inspired his feminist writings) knew one another as they all frequented the salon of Madame Helvetius, and were affiliated with the Societé des Amis des Noirs.

The period of the Revolution was ripe for those who wanted to claim rights for women, and Gouges’s ‘Declaration of the Rights of Woman’, and the ‘Draft of a Contract between Man and Woman’, which follows it, were certainly significant in that respect. Gouges advocated not only equality of political status between men and women, but also a series of reforms in marriage and family law, allowing divorce, provided that the economic well-being of children was preserved, and reforms which would guarantee that no one suffered because their parents were not married. Gouges even proposed that women who had been falsely promised marriage should receive compensation. She also argued that streetwalkers should be housed and looked after so that they could pursue their business in peace. This text remains controversial.

Gouges extended her quest for equality to slaves. Her play Zamore and Mirza was written to interest the French public in the fate of African slaves in America. It was performed by the French Theatre at the insistence of Brissot, co-founder of the Society for the Friends of the Blacks. She also published several articles and pamphlets in which she took on the arguments of the colonists, and argued strenuously for the abolition of slavery.

New and unfolding information and/or interpretations

Current Identification(s)

Olympe de Gouges is now honoured as one of the first proponents of feminism in France, but her work is still mostly unknown. Modern French editions and translations in other languages are scarce, especially considering the amount of work she produced. Historians have shown more of an interest in her since the celebration of the bicentennial of the Revolution in 1989, but she remains mostly excluded from philosophical debates.

less

Bibliography

Primary (selected):

Olivier Blanc lists all of Gouges’s 144 works, and most of them can be found on the Wikipedia page in her name: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Olympe_de_Gouges

One useful site containing translations by Clarissa Palmer of several of her tracts, prefaces, and plays is: http://www.olympedegouges.eu/

There are very few modern editions or translations of Olympe de Gouges’s writings although all or most of her work is available as facsimiles on websites such as Gallica, Google, Guttenberg, etc. Where possible I have referred to recent editions of her work, such as Gouges, Femme reveille-toi! Otherwise, the page numbers are to the original editions found online and listed in the bibliography.

Archival resources (selected):

Some of Gouges Manuscripts are held at the Archives Nationales (Paris, Saint Denis), and at the Bibliothè que Nationale (Paris).

Web resources (selected):

Clarissa Palmer’s translations of Gouges’s works, and biographical notice:

The online collection of the Bibliothè que Nationale, Gouges:

The British Library blog on Olympe de Gouges’s last work:

http://blogs.bl.uk/european/2013/11/olympe-de-gouges-and-les-trois-urnes.html

Liberty in Thy Name, blog on Gouges, Roland, and Grouchy: http://www.sandrineberges.com/liberty-in-thy-name/category/olympe-de-gouges

Issues with the Sources

While most of Gouges’s texts are available, very few have been edited or translated, and must therefore be read either as manuscripts or books printed in the 18th century. This goes some way to explain why there is so little scholarship on Gouges, and why it is still possible to deny that she had any impact through her writings. A study of the texts themselves, and of the responses to criticisms, show that Gouges’s work was widely read and influential.

A number of her works are no longer available as the manuscripts or printed copies were seized and destroyed when she was arrested, on the grounds that her writings could prove ‘infinitely dangerous’ and could ‘poison the public spirit.’

Comment

Your message was sent successfully