Birth

March 7th, 1498 in Kurki, Rajasthan 306101, IndiaEducation

Little is known about Mira’s education. Some sources claim that she was educated with her cousin Jaimal Rathore.

Death

March 7th, 2022 in Dwarka, Gujarat, IndiaReligion

HinduismMirabai was a poet, mystic, and a devotee of Krishna, the Hindu god. She is one of the most famous women poets in India and has around 400 poetic compositions attributed to her. These poems are called padas, which is a unit of Sanskrit meter composed of light and heavy syllables, usually a quarter of a four-line stanza. Her padas would have been sung according to a specific melody (rag), and they usually have a Dhruvak (refrain) for their opening or second line. Mira’s poems often focus on erotic themes of union and separation between her and her beloved Krishna. There are also many poems about the persecution she suffered from her family for her devotion.

Personal Information

Name(s)

Mirabai, Meera (मीराबाई)

Date and place of birth

c.1498, village of Kudki, Rajasthan, India (or Merta, Rajasthan)

Date and place of death

c. 1546, Dwarka, Gujarat, India

Family

Mirabai is thought to have been born into a Rajput royal family, possibly the Rathore clan, which ruled over the Mewar region in Rajasthan. Her mother, whose name is unknown, is said to have died when Mira was young. Mira’s father may have been Ratan Singh, and her grandfather was possibly Rao Dufdaji, who is known as the founder of Merta city.

Marriage and Family Life

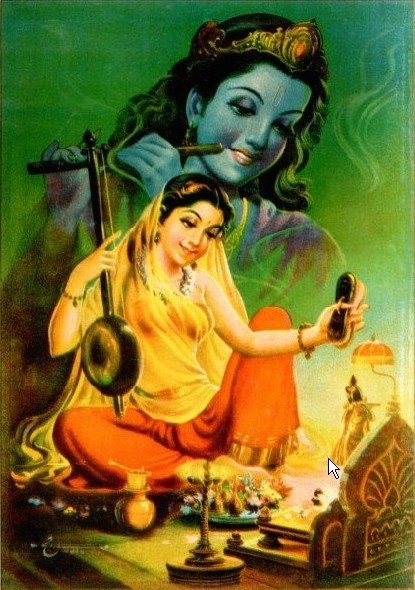

Legend says that while her mother was still alive, Mira saw an image of Krishna brought to her home by a holy man. She became so enamored of this image that her mother told her that Krishna would one day be her bridegroom. Mira later was married unwillingly to a man who is often identified as Bhoj Raj, the crown prince of Mewar and part of the Rajput Sisodia clan, which ruled over Mewar in Rajasthan. Her marriage was childless, and her husband died in battle shortly after their marriage. Mira refused to perform sati like a traditional Rajput widow and instead claimed that she was already married to Krishna. She started going to the temple in town to mingle with holy men and dance in front of an image of Krishna. As a consequence, her brother-in-law, referred to as “Rana” in her poems, tried to poison her.

Education

Little is known about Mira’s education. Some sources claim that she was educated with her cousin Jaimal Rathore (d.1568), the future Rajput hero. Based on her poetry, A.J. Alston suggests that Mira was educated in Hindu religious texts, the Vedas, Puranas, and Upanishads. She is also said to have received spiritual guidance from a guru sometimes identified as Ravidas, a saint and poet of the fifteenth century who belonged to a lower-caste family of leather workers.

Religion

Mira was devoted to the Hindu god Krishna. After she was widowed, she dedicated herself to spiritual life, traveling on pilgrimage to holy sites associated with Krishna such as Vrindavan and Dwarka, where, legend has it, her body melted into a statue of her beloved god.

less

Significance

Works/Agency

Approximately 400 poetic compositions are attributed to Mirabai. These poems are called padas, which is a unit of Sanskrit meter composed of light and heavy syllables, usually a quarter of a four-line stanza. Her padas would have been sung according to a specific melody (rag), and they usually have a Dhruvak (refrain) for their opening or second line. As is common in bhakti poetry, Mira’s name is often incorporated in the last line of her poems as a signature. Most of her padas are addressed to a friend, sometimes to a feminized friend. Some scholars propose that this friend was Lalita, who purportedly accompanied Mira when she left Merta to go to Vrindavan (Usha S. Nilson) though it seems like that the addressee is more generalized. Mira’s poem often focus on erotic themes of union and separation between her and her beloved Krishna. There are also many poems about the persecution she suffered from her family for her devotion.

Mira’s poems survive in three languages: Braj Bhasha, Rajasthani and Gujurati.

Reputation

What we know about Mirabai’s reputation during her life time derives largely from oral tradition. It is thus hard to distinguish between historical fact and legend. According to legend, for instance, Mira met Tulsidas the poet-saint, and Akbar, the great Mughal king, who, along with his musician Tansen, came to hear her sing. This suggests that she had a prominent reputation as a holy woman. However, since her life post-dates these historical figures, these encounters are probably legends.

There is not, in fact, much evidence for Mira’s popularity immediately after her death (see the section on sources below). Indeed, Parita Mukta argues that in Mira’s own state of Rajasthan, her name was often used as a term of abuse for promiscuous women since she had refused to accept the King of Chittor as her husband, defying Rajput male honor. The Rajputs apparently retaliated by omitting her name in written records. Mukta says that it was not until recently that Mira’s songs began to be sung openly in Rajasthan. Today, there are festivals and parks devoted to her in Rajasthan.

Elsewhere in India, Mira’s reputation increased over time, particularly starting in the eighteenth century, moving across linguistic, regional, and religious borders. Writers ranging from Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) (“Letter from a Wife” and Yogayog) to Kiran Nagarkar (1942-2019) (Cuckold) have invoked Mira as a character. There are many contemporary recordings and performances of Mira’s songs and life story as well as paintings, images, and posters depicting her (see the images section for two examples). Two television serials have been produced about her life, along with ten films, including Ellis Duncan's classic 1945 film starring singer M.S. Subbulakshmi as Mira. In 1972, Amar Chitra Katha produced comic book version of Mira’s life for children. In recent decades, Mira has become popular as feminist icon in India as part of a search for foremothers who defied patriarchal norms.

Outside of India, Mira is also well known. In the United States, physician and writer Tanmeet Sethi wrote about Mirabai in her short story Blue Tryst (2006). Mira’s life story has become a popular subject in cultural performances of the South Asian diaspora (See Martin, “Mirabai Comes to America”). Her songs have been translated into English by Robert Bly, Jane Hirschfield, Andrew Schelling, and others. She also appears in numerous books on topics ranging from spirituality to self-actualization, grief management, feminist philosophy of religion, and deep ecology. Life coaches and spiritual teachers, such as Mirabai Bush, Mirabai Starr, and Mirabai Devi, draw on Mira’s legacy. Bookstores and restaurants in the United States and Britain bear her name.

Academic interest in Mira has also increased over time. Early histories of her life tended to be shaped by hagiographical perspectives or by Rajput-oriented histories. More recent scholarship instead attempts to locate her historically (Frances Taft), to track her manuscript history (John Stratton Hawley), to examine contemporary communities of followers (Lindsey Harlan and Parita Mukta) and to track her reputation across time (Nancy M. Martin).

Transformation

The death of Mira’s husband was a significant turning point in her life. When she became a widow, she refused to perform sati, as was expected of Rajput women, and instead visited temples, went on pilgrimages and danced and sang in public, all of which ran contrary to the gender norms of her time. Mira took the opportunity that the liminal position of widowhood afforded her and mobilized this position to enter spiritual life.

Mira is considered part of the Bhakti movement. This was a trend that included both Hindu and Muslim holy figures. It is generally thought to have begun in south India in the eighth century and spread northward, promoting a kind of democratization of religion. Bhakti poets challenged the caste system and the ritualism controlled by Brahminical priests and instead advocated for a more personal form of devotion and immediate connection to the divine. Many lower caste and female devotees participated in this movement and composed poetry in the vernacular.

While Mirabai is widely regarded as a saint within the Bhakti movement, she did not entirely conform with its rejection of traditional hierarchies. Neera Desai has pointed out that Mira’s poems often uphold a woman’s traditional place in the family: her imagery is drawn from the household and traditional duties of a wife are celebrated, as she imagines herself as the dasi (slave) of Krishna. Unlike other Bhaktas, she also did not explicitly question the hierarchies of caste although she did take the lower-caste Ravidas as her guru.

Legacy and Influence

Schools, temples, scholarships and even bookstores are named in honor of Mirabai.

Mirabai Temple, Vrindavan

Meera Temple, Chittorgargh Fort, Rajasthan

Mirabai Scholarships for Nursing Students (https://missionwithgloryfoundation.org/scholarship-india-1)

Meer bai Institute of Technology, Delhi

St. Mira’s School, Pune (https://www.stmiraschool.org/)

Mirabai Book store, Woodstock, NY (https://www.mirabai.com/)

Contemporary Identifications

Mirabai is most commonly included within the disciplines of Religious Studies and South Asian Studies.

Networks

As mentioned above, Mirabai is generally included as an important saint within the Bhakti movement. She also often appears in both scholarly and nonacademic comparative studies of religious women, thus forming part of a transhistorical network of holy women. For instance, she features in Holly Hillgardner’s recent comparative study of Hindu and Christian practices of non-attachment and in Elisabeth Schuessler Fiorenza and M. Shawn Copeland’s Feminist Theology in Different Contexts (1996).

less

Controversies

Controversy

During her lifetime, Mira faced significant adversity from the Rajput aristocracy. Through her rejection of widowhood and her subsequent pilgrimages, Mira violated the norms for women in Rajput society. This transgression, along with her acceptance of Ravidas, a lower-caste saint, as her Guru, subverted traditional systems of authority. Hence, after her death, Mira became a symbol of resistance towards authority, and the performance of her songs by peasants and artisans served to subvert caste-based hierarchies.

Feminism/Social Activism

The poetry and hagiography of Mira depict her as a woman who defied traditional patterns of womanhood in her devotion towards Krishna. She has offered a source of inspiration for contemporary feminists and appeared in publications such as Feminism in India.

Issues with the sources

Historians have long disputed details of Mira’s life since much of her biography derives from oral tradition rather than from historical documents. Most modern accounts of Mira’s life stem from Munshi Devi Prasad’s “Miram Bai ka Jivan-Charitra” (1905), but this is largely an imaginative construction that aims to reconcile episodes described in Mira’s poems with the history of the Rajputs. Many subsequent attempts to locate Mira historically, such as identifying her husband as Bhoj Raj, have been disputed. Frances Taft attempted to locate Mirabai in a “modern historical sense” by looking at Rajasthani genealogical records and found brief mentions of Mira in several of these documents, such as a mid-seventeenth century genealogy from Jodhpur by Munhata Nainsi. The bulk of early references to Mira, however, as John Stratton Hawley points out, appear in hagiographic material. The Bhaktamal, an early hagiographical text by Nabhadas, mentions Mira, as does accompanying commentary by Priya Das (c. 1712).

Not only is reliable historical evidence for Mira’s life lacking, but her corpus of poetry cannot definitively be associated with a single historical person. As Hawley points out, only 22 poems bearing Mira’s signature have been found in manuscripts predating 1700, and 15 of these are currently unlocatable. Only two of the 22 poems date back to the sixteenth century. Her work did not appear in anthologies until the late eighteenth century. There are several possible reasons for the dearth of poems dated close to Mira’s lifetime. First, she may have been excluded from devotional anthologies because she was a woman or because her poetry was regarded as insufficiently poetic to be preserved in writing. Second, it may be that much of the poetry now bearing Mira’s signature was written in response to her legend by an array of later writers. Supporting this second conclusion, Hawley argues that many of her poems “must have been written by other ‘Miras’ than the original one, if ever indeed she existed at all” (Hawley, Songs of the Saints of India, 123). In fact, Mira’s signature “may well have served as an umbrella for a number of other female poets, and the force of her life story doubtless drew poets of both genders to her banner” (Hawley, Three Bhakti Poets, 31). While the historical Mira is uncertain, the force of her presence in Indian culture and in spiritual life more broadly is indisputable.

less

Bibliography

Primary

Hindi Editions:

Mirabai Ki Padawali. Edited by Acharya Parashuram Chaturvedi. Prayag: Hindi Sahitya Sammelan, 1993.

Mirabai Aur Unaki Padawali. Edited by Desharaj Singh Bhati. Delhi: Ashok Prakashan, 1995.

English Translations:

The Devotional Poems of Mirabai. Translated by A. J. Alston. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas, 1980.

Mirabai: Ecstatic Poems. Translated by Robert Bly and Jane Hirshfield. Boston: Beacon Press, 2004.

Usha Nilsson, Mira Bai (Rajasthani Poetess). Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 1997.

For Love Of The Dark One: Songs Of Mirabai. Translated by Andrew Schelling. Boston: Shambala, 1993.

Historical sources:

Nabhadas et. al. Sri Bhaktamal with the Bhaktirasabodhini commentary of Priyadas. Edited by Sitaramansaran Bhagvanprasad. Lucknow: Tejkumar Press, 1969

Archival resources

Guru Granth Sahib, Kartarpur Manuscript (1604), Gurdwara Thum Sahib

MS 30346, folios 43, 44, 51, Rajasthani and Hindi collection of the Rajasthan Oriental Research Institute, Jodhpur

MS 689, Vidya Sabha Library, Ahmedabad (C.L. Prabhat, Mira, Jivan aur Kavya, p. 467)

MS 938/939/8, Sanjay Sharma Museum and Research Institute, Jaipur

Secondary Sources (selected recent scholarship)

Desai, Nira. “Women in the Bhakti Movement.” Sandarbh 1.2 (1983): 92-100.

Harlan, Lindsay. “Abandoning Shame: Mīrā and the Margins of Marriage.” In From the Margins of Hindu Marriage. Edited by Lindsay Harlan and Paul B.Courtright. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

--. Religion and Rajput Women: The Ethic of Protection in Contemporary Narratives. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992.

Hawley, John Stratton, and Mark Juergensmeyer. Songs of the Saints of India. Revised Edition. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Hawley, John. Three Bhakti Voices: Mirabai, Surdas, and Kabir in Their Time and Ours. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Hilgardner, Holly. Longing and Letting Go: Christian and Hindu Practices of Passionate Non-attachment. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Kishwar, Madhu and Ruth Vanita. “Poison to Nectar: The Life and Work of Mirabai.” Special Issue: Women Bhakta Poets. (January–June 1989): 74–93.

Martin, Nancy M. “Mirabai Comes to America: The Translation and Transformation of a Saint.” The Journal of Hindu Studies 3.1 (April 2010): 12–35.

--. “Rajasthan: Mirabai and Her Poetry.” In Krishna: A Source Book. Edited by Edwin Bryant, 241–254. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

--. “Mirabai: Inscribed in Text, Embodied in Life.” Vaisnavi: Women and the Worship of Krishna. Edited by Steven Rosen, 7-46. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1996.

Mukta, Parita. Upholding the Common Life: The Community of Mirabai. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Pandey, SM. and Zide, Norman. “Mīrābāī and Her Contributions to the Bhakti Movement.” History of Religions 5. 1 (Summer, 1965): 54-73.

Taft, Frances. “The Elusive Historical Mirabai: A Note.” In Multiple Histories: Culture and Society in the study of Rajasthan. Edited by Lawrence A. Babb, Varsha Joshi and Michael Meister, 313-35. Jaipur, Rawat Publications, 2002.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully