Birth

September 8th, 1820 in Saint Pancras, London, UKEducation

Boarding SchoolDeath

July 3rd, 1897 in 15 Sefton St, Liverpool L3, UKReligion

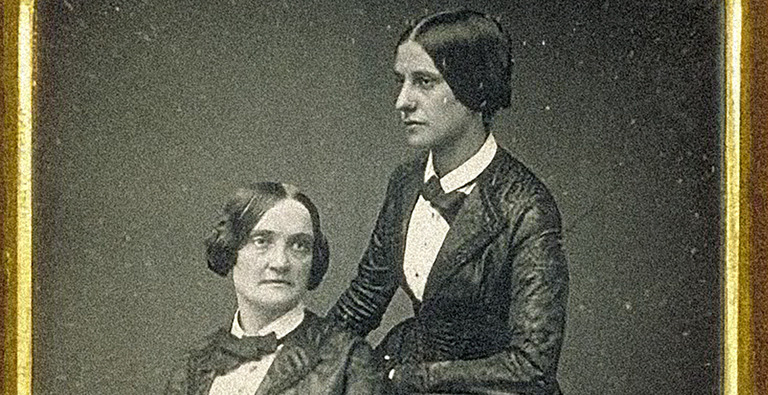

Christianity, AnglicanMatilda Mary Hays was a writer, social activist, and openly lesbian woman living in England during the Victorian era. She is known for her novels, journalism, and literary translations depicting the plight of women trying to remain socially and financially independent outside of marriage. Matilda Mary Hays lived with and was taught by her aunt Mary Hays, acclaimed author and feminist, for nine years. She followed in her aunt's tradition, promoting women's rights and social progressive ideas.

Personal Information

Name(s)

Matilda Mary Hays

Date and place of birth

September 8, 1820, at 16 Doughty Street, near Grays Inn Lane, London; christened at the Old Church, St. Pancras, London, on October 7, 1820.

Date and place of death

July 3, 1897, at 15 Sefton Drive, Toxteth Park, Liverpool.

Family

Mother: Elizabeth Atkinson Breese Hays (c. 1781-12 September 1832); her mother had previously been married to a Mr. Breese and had several children from that marriage.

Father: John Hays (1768-1862), corn factor and author; he published Observations on Existing Corn Laws (1824, 2nd ed. 1828) and Remarks on the Late Crisis in the Corn Trade (1847). He was the younger brother of the novelists Mary Hays (1759-1843) and Elizabeth Hays Lanfear (1765/66-1825); Matilda Mary Hays was one of Mary Hays’s favorite nieces, a fact made known in Crabb Robinson’s Diary and Reminiscences.

Marriage and Family Life

Between 1824 and 1832 Matilda Mary Hays and her family lived at Norwood Lodge, a massive estate located seven miles due south of central London; after the death of her mother in 1832, the family moved to Camberwell, where Mary Hays lived with her and the family for the next nine years, serving as Matilda’s primary educator. Matilda Hays had three half-sisters from her mother’s first marriage: Clara (b. c. 1801), Hannah (b. 1805) and Elizabeth Breese (b. 1810). She had five siblings from her parents: Elizabeth (b. 4 February 1813), Anna (b. 17 April 1814), Henry (b. 24 March 1817), Susanna (b. 20 September 1818), and Albert (b. 22 June 1823). Matilda Mary Hays, like Mary Hays, never married, though she lived at various times as the primary romantic partner of American actress Charlotte Cushman (1816-76) and the poet Adelaide Proctor (1825-64). It appears Matilda Mary did not remain in close contact with the large cadre of her cousins (more than fifty) in the Dunkin, Hays, Wedd, Palmer, Lee, and Francis families, though her aunt Mary Hays left her £10 in her will and just before her death in 1843 composed a special message designed for Matilda Mary.

Education

She probably attended a boarding school in her youth (her father certainly could have afforded the expenditure), but her finishing education appears to have come from Mary Hays during her time living with her brother’s family between 1832 and 1841. Given the nature of Matilda Mary Hays’s writing career, the influence of her aunt is unmistakable.

Religion

Her father was raised in the Particular Baptist church in Gainsford Street, Southwark, but he appears to have conformed to the Anglican Church upon his marriage to Elizabeth Breese. In contrast to the devoted loyalty to religious Dissent (Unitarianism) of her two aunts, Mary Hays and Elizabeth Hays Lanfear, Matilda Mary appears to have been largely indifferent toward any religious preferences, either among the Established Church or Dissenting sects.

Transformation(s)

Without question, the nine years in which she lived with and was taught by Mary Hays (this would have been between the ages of 12 and 21) were transformative in the development of her ideas, opinions, and writing abilities, especially her stance on women’s education, marriage, and social and intellectual freedoms. Though not necessarily a transformation in her private life, her coming out openly as a lesbian nevertheless a significant and bold public moment in women’s history.

Contemporaneous Network(s)

Her earliest circle of influence was that of her family, most particularly, her aunt, Mary Hays, and her aunt’s close friend, Henry Crabb Robinson (1775-1867), from whom she sought advice in May 1844 about seeking a publisher for her first novel. Her early translations of George Sand brought her into the circle of Eliza Ashurst, Edmund Larken and the publisher E. Churton. She collaborated with Eliza Cook around 1848 on the latter’s self-named journal devoted largely to women’s issues, temperance, and social programs for the poor. In 1858 she worked with Barbara Bodichon and Bessie Rayner Parkes in the founding of the English Woman’s Journal (1858-64), assisted financially by Theodosia Blacker (Lady Monson) (1803–1891). Other circles involved the actress Charlotte Cushman (1816-76), the poet Adelaide Proctor (1825-64).

less

Significance

Works/Agency

Various periodical contributions to the Mirror and Ainsworth’s Magazine as well as the English Woman’s Journal.

Helen Stanley. London: Churton, 1846.

The Works of George Sand. Translated into English by Matilda Mary Hays (1847-51), assisted by Eliza Ashurst and Edmund Larken. Volumes 1-6 first published in London by E. Churton in 1847.

The Last Aldini. By George Sand. Translated by Matilda M. Hays, author of “Helen Stanley.” London: E. Churton, 26, Holles Street. 1847. Vol. 1.

Simon. By George Sand. Translated by Matilda M. Hays, author of “Helen Stanley.” London: E. Churton, 26, Holles Street. 1847. Vol. 2.

André. By George Sand. Translated by Eliza A. Ashurst. Edited by Matilda M. Hays, author of “Helen Stanley.” London: E. Churton, 26, Holles Street. 1847. Vol. 2.

The Mosaic Masters; The Orco: A Tradition of the Austrian Rule in Venice; and Fanchette. By George Sand. Translated by Eliza A. Ashurst. Edited by Matilda M. Hays, author of “Helen Stanley.” London: E. Churton, 26, Holles Street. 1847. Vol. 2.

Mauprat. By George Sand. Translated by Matilda M. Hays, author of “Helen Stanley.” London: E. Churton, 26, Holles Street. 1847. Vol. 3.

The Companion of the Tour of France. By George Sand. Translated by Matilda M. Hays, author of “Helen Stanley.” London: E. Churton, 26, Holles Street. 1847. Vol. 4.

The Miller of Angibault. By George Sand. Translated by The Rev. Edmund R. Larken, M.A. Rector of Burton by Lincoln, and Chaplain to the Rt. Hon. the Lord Monson. Edited by Matilda M. Hays, author of “Helen Stanley.” London: E. Churton, 26, Holles Street. 1847. Vol. 5.

Letters of a Traveller. By George Sand. Translated by Eliza A. Ashurst. Edited by Matilda M. Hays, author of “Helen Stanley.” London: E. Churton, 26, Holles Street. 1847. Vol. 6.

Fadette. A Domestic Story. From the French. By Matilda M. Hays. New York: Putnam, 1851. British library copy. Inscription to Charlotte Cushman.

---, ed. English Woman’s Journal, 1858-64.

---, ed. Legends and Lyrics: A Book of Verses, by Adelaide Procter, Adelaide. London: Bell and Daldy, 1861.

Adrienne Hope. London: T. Cautley, 1866.

Reputation

During her lifetime she was known primarily as a minor novelist, the translator of George Sand, and a progressive journalist for women’s rights. Surprisingly, her live-in relationships with several prominent women were never a secret. Such knowledge, however, damaged her reputation at that time, much like various accusations against the character of her aunt continued to haunt her reputation into the 20th century. She has resurfaced in accounts of modern feminism, lesbianism, and women writers and actresses of the 19th century, but a complete and accurate biographical account of her has yet to be compiled.

Legacy and Influence

Matilda Mary Hays followed in the footsteps of her aunts Mary Hays and Elizabeth Hays Lanfear not only as a promoter of women’s issues and social progressive ideals but also in composing and translating novels depicting the plight of women trying to remain socially and financially independent outside of marriage. Matilda Mary was a pioneer in feminist periodicals through her work with The English Woman’s Journal. She was a pioneer among lesbians, dressing as a man from the waist up and living openly with at least three women in her lifetime. As critical attention on Matilda Mary Hays continues to grow, her influence and importance as a writer and social activist will become clearer. Perhaps one of the most telling contemporary comments on Matilda Mary Hays came from her aunt’s close friend, Crabb Robinson, who added the following note to his Reminiscences for 1819 (he wrote the note on 31 July 1859):

“It is a curious fact, that a niece of Mary Hayes (a daughter of her Brother John,) is become an authoress, being as her aunt was, in advance of the age – if advance be the proper term, which it is to be hoped, it is not; for that implies that the age is to follow = She is the translatress of several of George Sand’s novels!!!’ (Crabb Robinson Reminiscences, 1819, vol. 2, f. 243, Crabb Robinson Archive, Dr. Williams’s Library, London).

less

Controversies

Controversy

Her greatest controversy was her openly known relationships with several prominent women in England during the height of the Victorian age, though her efforts to translate the novels of George Sand met with some criticism in the late 1840s.

New and unfolding information and/or interpretations

Her familial relationship with the novelists Mary Hays and Elizabeth Hays Lanfear, the presence of her three letters c. 1848 residing at the Pennsylvania Historical Society, Philadelphia, and references to her in the diary of Henry Crabb Robinson.

less

Bibliography

Sources

Primary (selected):

Merrill, Lisa. When Romeo was a Woman: Charlotte Cushman and Her Circle of Female Spectators. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000.

Chen, Li-ching. “‘Like the Lion in his Den’: Mary Hays, Solitude and Women’s Enfranchisement.” European Romantic Review 32.3 (2021): 335-54.

Classe, Olive, ed. Encyclopedia of Literary Translation into English. London: Fitzroy Dearborn, 2000. Vol. 2, p. 1226.

Archival resources (selected):

Matilda Hays letters to Elizabeth Neall Gay, 1841, James Gay Manuscript Collection, Columbia University, New York.

Three letters by Matilda Mary Hays, 1848, Gratz ALS Collection, Box 132, Folder 29, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; the paucity of manuscript sources will continue to hamper scholarly studies of her life and career.

Web resources (selected):

“Matilda Hays.” The Orlando Project.

http://orlando.cambridge.org/public/svPeople?person_id=haysm2

Merrill, Lisa. “Hays, Matilda Mary (1820?-1897). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://www.oxforddnb.com

“Matilda Hays.” Mary Hays: Life, Writings, and Correspondence, at www.maryhayslifewritingscorrespondence.com

Issues with the sources

The primary issue with sources to date is their omission of the familial connection between Matilda Mary Hays and the novelist Mary Hays, and the letters by Matilda Hays at the Pennsylvania Historical Society.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully