Birth

March 25, 1826, Cicero, New York

Death

March 8, 1898, Chicago, Illinois

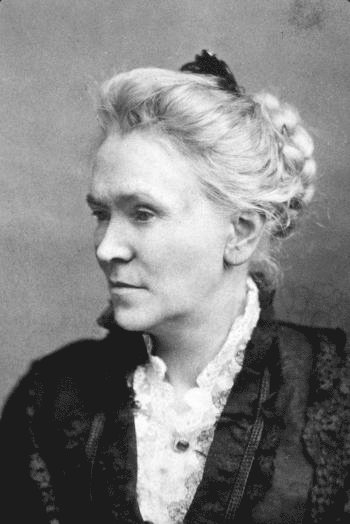

Matilda Joslyn Gage was a leading figure in the women’s rights movement in the United States, particularly the National Woman Suffrage Association, the New York State Woman Suffrage Association, and, later, the Woman’s National Liberal Union. She was also a prolific writer, authoring numerous pamphlets and books.

Personal Information

Name(s) Matilda Joslyn Gage

Date and place of birth

March 25, 1826, Cicero, New York

Date and place of death

March 8, 1898, Chicago, Illinois

Family

Mother Helen Joslyn

Father Dr Hezekiah Joslyn (1797-1865) – abolitionist and physician

Marriage and Family Life

Married Henry H. Gage, a merchant, on 6th January 1845. They had five children: Helen, Thomas, Charles, Julia, and Maud. The youngest child, Maud, went on to marry L. Frank Baum, a children’s author who is best known for writing The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

Education (short version)

Gage was educated at home and then at the Clinton Liberal Institution in Clinton, New York.

Education (longer version) The exact details of Gage’s education are unknown. She was educated at home by her parents. Her father took a great interest in her education and personally oversaw much of her learning. Gage later attended the female division of the Clinton Liberal Institute from 1841-1842. Clara Barton (1821-1912), self-taught Civil War nurse and Founder of the American Red Cross, attended the school's female division beginning in 1850.

Religion

Outspoken critic of organised religion, especially Christianity.

Transformation(s)

Gage’s family home in Cicero, New York, was a stop on the Underground Railroad. Her father, Dr. Hezekiah Joslyn, was a prominent abolitionist. He is believed to have co-founded the Liberty Party, a political party for abolitionists in 1840. Reflecting on her childhood, Gage would later say: “I think I was born with a hatred of oppression, and, too, in my father’s house, I was trained in the anti-slavery ranks.”

As well as abolition, Gage was heavily involved in the movement for women’s suffrage. Probably due to family commitments, she was absent from the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848, but she gave her first public speech at the third National Women’s Rights Convention in Syracuse in 1852. From then, Gage became a leading figure in the suffrage movement, founding the National Woman Suffrage Association in 1869, as well as the New York State Woman Suffrage Association. She served as president of the latter for nine years. Throughout the 1850s and 1860s, Gage balanced activism with the expected roles of wife and mother. Once her children had grown, she became more involved in writing, speaking, and social justice work.

Contemporaneous Network(s)

Gage was a leading figure in the women’s rights movement in the United States, particularly the National Woman Suffrage Association, the New York State Woman Suffrage Association, and, later, the Woman’s National Liberal Union.

less

Significance

Works/Agency

Gage was a prolific writer during her lifetime and authored numerous pamphlets and books, including:

Joslyn Gage, Matilda. History of Woman Suffrage, 1881, Chapters by Cady Stanton, E., Anthony, S.B., Gage, M. E. J., Harper, I.H. (published again in 1985 by Salem NH: Ayer Company).

Joslyn Gage, Matilda. Speech at the National Woman’s Rights Convention, 1852. From National Susan B. Anthony Museum & House. https://susanb.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Matilda-Joslyn-Gage-Syracuse-NY-1852.pdf (accessed April 27th, 2023).

Joslyn Gage, Matilda. The Dangers of the Hour. From Speeches on Social Justice. http://www.sojust.net/speeches/mgage_dangers.html (accessed April 27th, 2023).

Joslyn Gage, Matilda. “Woman As An Inventor.” The North American Review vol. 136, no. 318 (May 1883): 478-489, JSTOR.

Joslyn Gage, Matilda. Woman, Church, and State: A Historical Account of the Status of Woman Through the Christian Ages: With Reminiscences of the Matriarchate (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr Company, 1893).

In 1878, Gage bought a journal called Ballot Box upon the retirement of its editor, Sarah R. L. Williams. She changed the publication name to National Citizen and Ballot Box. Gage used the journal to publish editorials on a wide range of social justice issues, with a particular focus on women and women’s rights. She also shared snippets of her research into women’s history with her readers.

Contemporaneous Identifications:

Reputation

For most of her life, Gage was a widely respected and well-known leader in the women’s rights movement. She was also a popular figure in the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. Gage claimed to have been adopted by this Indigenous community: “I received the name of Ka-ron-ien-ha-wi,’ or ‘Sky Carrier.”

From the 1890s, her criticism of Christianity and departure from the largest women’s rights organisation in the United States impacted her reputation. Specifically, many of the women she had once worked with distanced themselves from Gage and her anti-Christian views. This contributed to her near-disappearance from the historical record upon her death.

Legacy and Influence

Gage is perhaps best known for being the namesake of the ‘Matilda Effect,’ a term that was coined by the historian of science, Margaret Rossiter, in 1993. The Matilda Effect refers to the historic bias against recognising the achievements of women in science. Although not a scientist, Gage wrote about the forgotten and ignored contributions of women to science in the pamphlet, Woman as an Inventor, in 1870. The pamphlet established a long history of female innovation, beginning in antiquity and ending in the 19th century. Perhaps the most controversial assertion is that the invention of the cotton gin was by a woman called Catherine Littlefield Greene and not by Eli Whitney. However, like the women scientists she identified, Gage was largely forgotten by historians and the wider public after her death in 1898.

The ‘rediscovery’ of Gage’s work in the late 20th century has greatly improved her historical reputation. She is now widely acknowledged as a leading figure in the women’s suffrage movement in the United States.

less

Controversies

Controversy

Gage courted controversy throughout her life. In 1850 she signed a petition stating that she would willingly spend six months in prison and pay a substantial fine for breaking the Fugitive Slave Act. It is unclear how many formerly enslaved people Gage and her husband harboured before the Thirteenth Amendment passed. For much of her adult life, Gage argued that Christianity was responsible for women’s subjugation, both in the home and the public sphere. In 1890, the National Woman’s Suffrage Association (NWSA), an organisation that she had co-founded, merged with the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). The result was the creation of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), a group with a more conservative, Christian agenda. In response, Gage left and formed the Woman’s National Liberal Union, for which she served as president. In 1893, she published Woman, Church, and State, a book that outlined how the Christian Church systematically oppressed women, beginning with the destruction of prehistoric matriarchies. She also called the European Witch Trials a “holocaust” that resulted in the deaths of millions of women who were practicing an ancient form of goddess worship. This book was later rejected by the NAWSA and Gage was shunned by many suffrage activists. Her critique of Christianity was a leading factor in her erasure from the history of the women’s rights movement.

Finally, Gage was also an advocate for the rights of Indigenous Americans. She worked closely with the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, documenting the different levels of equity between white American women and Haudenosaunee women. She used her journal, The National Citizen and Ballot Box, to argue in favour of citizenship for Indigenous Americans, which contravened the dominant attitude of the time.

less

Clusters & Search Terms

Current Identification(s)

History, history of science, women’s studies, civil rights

Clusters

Women’s suffrage activists, e.g. Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Search Terms

Women’s suffrage, abolition, women writers, women and religion, Church, 19th century

less

Bibliography

Primary (selected)

Joslyn Gage, Matilda. History of Woman Suffrage, 1881, Chapters by Cady Stanton, E., Anthony, S.B., Gage, M. E. J., Harper, I.H. (published again in 1985 by Salem NH: Ayer Company)

Joslyn Gage, Matilda. Woman, Church, and State: A Historical Account of the Status of Woman Through the Christian Ages: With Reminiscences of the Matriarchate (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr Company, 1893)

Archival Resources (selected):

Joslyn Gage, Matilda. Speech at the National Woman’s Rights Convention, 1852. From National Susan B. Anthony Museum & House. https://susanb.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Matilda-Joslyn-Gage-Syracuse-NY-1852.pdf (accessed April 27th, 2023).

Joslyn Gage, Matilda. The Dangers of the Hour. From Speeches on Social Justice. http://www.sojust.net/speeches/mgage_dangers.html (accessed April 27th, 2023).

Joslyn Gage, Matilda. “Woman As An Inventor.” The North American Review vol. 136, no. 318 (May 1883): 478-489, JSTOR.

Web Resources (selected):

Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation, https://matildajoslyngage.org/home.

Unitarian Universalist Church of Utica, http://www.uuutica.org/about-us/history-of-uu-utica/area-uu-history/

New York Heritage Digital Collections, https://cdm16694.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/fpfl/search/searchterm/Clinton%20Liberal%20Institute/field/subjea/mode/exact/conn/and

Issues with the Sources:

VI. Images

Comment

Your message was sent successfully