Birth

April 27th, 1759 in Primrose St, London EC2A, UKEducation

Day SchoolDeath

Buried, Old St Pancras.

Religion

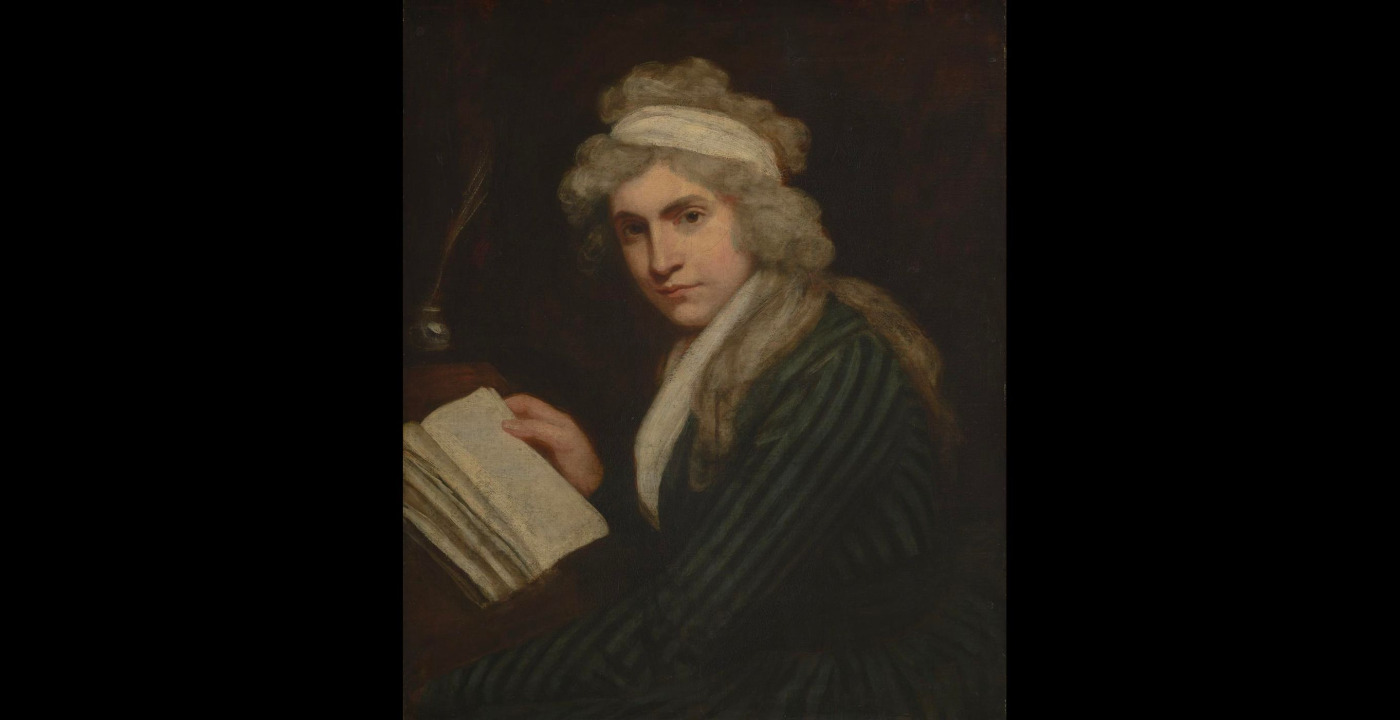

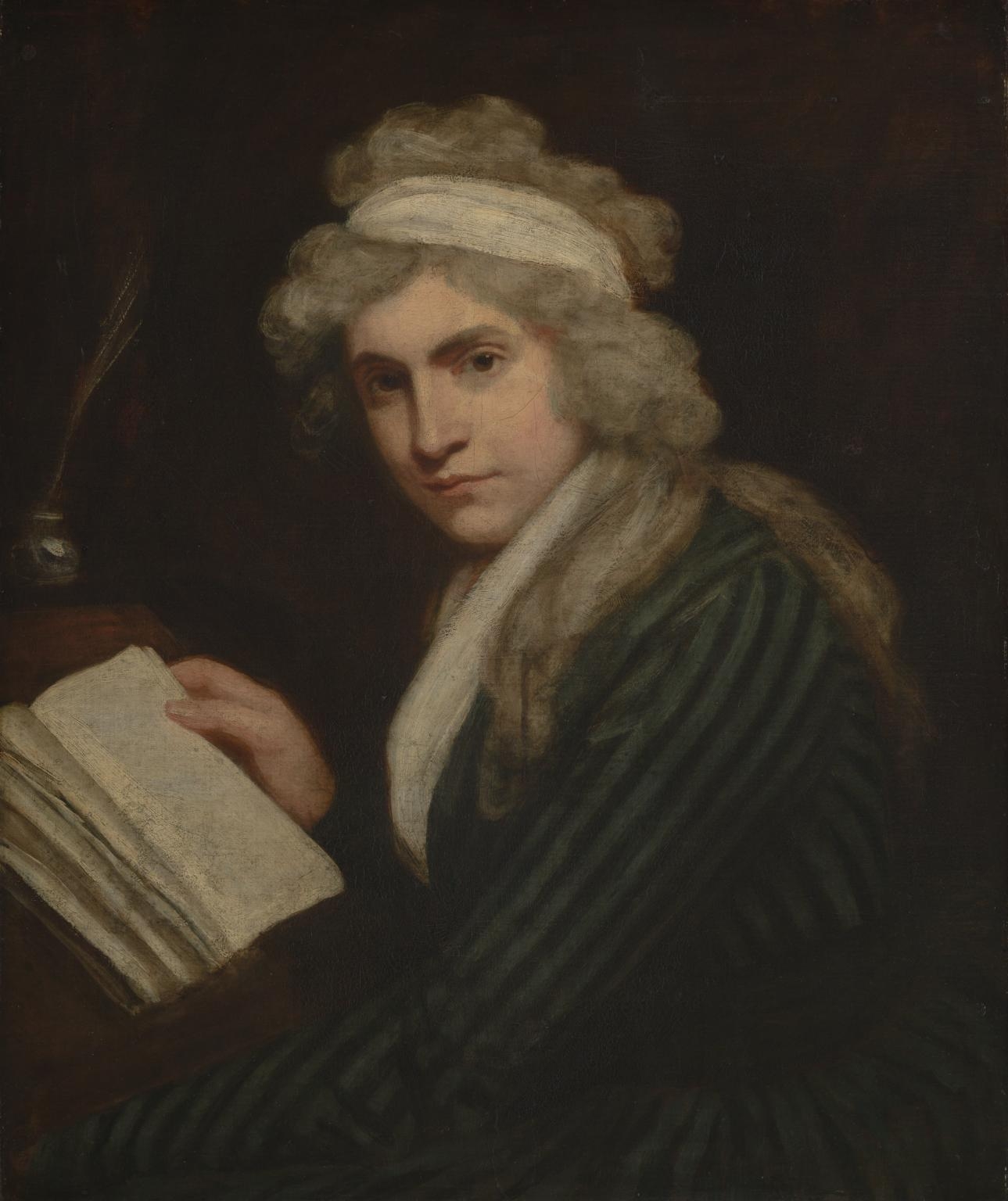

AnglicanMary Wollstonecraft was a moral and political philosopher and writer who was a radical advocate for women's equality and their right to education. She is best known for her two political treatises, A Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790) and A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). She was the mother of Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein.

Personal Information

Name(s)

Mary Wollstonecraft also went by the name of Mary Imlay and Mary Godwin.

Date and place of birth

27 April 1759, Primrose Street, London.

Death and place of death

10 September 1797, London. Buried, Old St Pancras.

Mother:

Elizabeth Dickson, connected to the landed gentry of Ballyshannon, County Donegal, Ireland (? – 1782)

Father:

Edward John Wollstonecraft, originally a Spitalfields weaver (1737? - ?). Her father inherited money in the mid-1760s and the family moved out of London, but her father’s ambitions to join the landed gentry and his endeavours in agriculture were not successful. According to Wollstonecraft’s account, her father drank and was violent. The family returned to London when Wollstonecraft was around sixteen, settling in the village of Hoxton, just north of London. By 1779, the inheritance was lost, leaving the family in financial insecurity. Wollstonecraft had two sisters (Elizabeth [known as Eliza or Bess] b. 1763 and Everina 1765-1843) and four brothers. She was heavily involved emotionally and financially in her siblings lives, in particular those of her two sisters and her younger brother, Charles.

Marriage and Family Life

In August 1793 Wollstonecraft registered at the American Embassy in Paris as the wife of Gilbert Imlay (1754?-1828?) of New Jersey and Kentucky. She had met him in Revolutionary Paris and the two were lovers but did not marry. Their daughter, Franșoise (Fanny) Imlay (1794-1816), was born in May. Imlay seems to have tired of Wollstonecraft soon after the birth of their daughter, and their relationship was over by June 1795. Left on her own with a child and with no clear means to support herself, in the final months of her relationship with Imlay Wollstonecraft twice attempted to take her own life.

In March 1797 Wollstonecraft married the English philosopher and novelist William Godwin (1756-1836). She was already pregnant when they married and she died from complications 10 days after giving birth to their daughter, Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin (1797-1851), later Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus (1818).

Education

Wollstonecraft went to her local day school until she was fifteen, where she received a basic education. However, her chief education came through friendships and reading and she regarded herself as largely self-educated. At the age of fourteen, she formed a close friendship with Jane Arden, whose father invited her to join in some of her lessons. Once back in London, she formed a friendship with a clergyman, Reverend Mr Clare of Hoxton and his wife, who seem to have encouraged her reading, and with Frances (Fanny) Blood, with whom she exchanged letters (now lost) and whose writing she admired.

In 1784, at the age of 25, having endured a stifling period as a lady’s companion, then as nurse to her dying mother, Wollstonecraft set up a school in Newington Green with her two sisters (she had helped Bess to leave her violent husband), and her friend Fanny Blood. Her first work, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1787) would late respond to what she saw as the demeaning limits of female education. She wrote, “I wish them to be taught to think” (Works 4: 11). This would later become one of the chief tenets of her political treatises. The school failed after Fanny Blood’s marriage, and a period during which Wollstonecraft was absent in Lisbon attending Fanny’s deathbed. The Wollstonecraft sisters were left heavily in debt.

In the fall of 1786 Wollstonecraft travelled to Ireland where she worked as a governess in the Kingsborough family. While in Ireland, Wollstonecraft first read Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Emile (1762), which became a source of inspiration as well as target of intense criticism for her. She wrote to her sister Everina that she “love[s] his paradoxes” (Letters: 114). In June 1787, she moved back to London to dedicate herself to her writing. She quickly established herself as an educational and political writer, as a novelist, a translator and a regular contributor to Joseph Johnson’s newly established periodical Analytical Review, which provided an important public forum for British reformers of the period.

Religion

Though raised an Anglican and remaining a member of the Church of England until her death, in Newington Green Wollstonecraft became closely involved with the community of radical Rational Dissenters who shaped both her political and religious views. Most notably, this group included the eminent preacher, mathematician and moral philosopher Dr Richard Price, who taught doctrines of equality, liberty, and religious utopianism, and who linked religious freedoms to political freedoms. The religion Wollstonecraft learned from Price emphasized that “God is Justice itself” and that to submit to him is “to submit to the authority of reason”, as she later wrote in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (Works 5: 170). The Rational Dissenters emphasized that in order to be a moral agent one must govern oneself in accordance with reason. Someone who merely obeys the will of another cannot be truly moral. This principle informed Wollstonecraft’s feminism and her demand that women must be given the opportunity to educate their reason on the same terms as men.

Contemporaneous Network(s)

Wollstonecraft’s early life was enriched by friendships with women, including her sisters and Fanny Blood, around whom she formed close intellectual and emotional support networks, sustained in part through letter writing.

After she moved back to London in 1787, and began her career as an author in earnest, she became a part of the circle of radical intellectuals centered around her publisher, Joseph Johnson and the Analytical Review. Johnson played an essential role in enabling her to live independently, acting as her banker, mentor and friend. She was often the only woman at the famous weekly dinners at which the circle gathered, which included Thomas Paine, author of Rights of Man (1791), William Godwin, the painter Henry Fuseli (1741-1825), as well as noted abolitionists and Dissenters. Novelist and intellectual Mary Hays (1759–1843), who would later become a close friend and write one of the first biographies of life, also formed part of the circle.

Wollstonecraft was at the center of a group of radical women in the 1790s, all of whom were working through the implications of the French Revolution for society in general, but in particular for women. When she crossed the channel to Revolutionary Paris, Wollstonecraft met English novelist and poet, Helen Maria Williams (1759 –1827), whose own dispatches back to England had been some of the most formative and jubilant accounts of the early Revolution. Through Williams’ weekly Sunday evening Salons, Wollstonecraft gained access to French political and intellectual circles associated with the Girondist faction. Williams’ guests included writer and educator Mme de Genlis (1746-1830) and Mme Roland (1754-1793), who died at the guillotine during the Terror.

less

Significance

Works/Agency

Wollstonecraft’s early works belong to the genre of educational writings. Her first book, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1787), consists of short chapters on varied topics such as The Nursery, The Fine Arts, and Reading. In the second chapter, on Moral Discipline, Wollstonecraft refers to John Locke’s system of education and she follows Locke particularly when emphasizing that children need to learn to use their own reason rather than blindly obey the whims of their parents. Original Stories from Real Life (1788) is a pedagogical children’s book, printed in a second edition 1791 with grim – and beautiful – illustrations by William Blake. The stories all contain a moral message and they are told to two girls whose education has been neglected and who are now being re-educated by the reasonable and firm, but also kind, Mrs. Mason. During this time Wollstonecraft also published an edited volume with texts suitable for the education of girls, The Female Reader (1789), and a translation of a French work by Jacques Necker, Of the Importance of Religious Opinions (1788).

Wollstonecraft is best known for her two political treatises, A Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790) and A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). A Vindication of the Rights of Men was one of the first British responses to the French Revolution. Wollstonecraft wrote in the defence of Richard Price’s celebration of the Revolution and in critical response to Edmund Burke’s conservative criticism of Price. Written over four weeks, printed page-by-page as it was written, and first published anonymously, it mounts a powerful argument in support of the Revolution and for human progress and the right of all to develop their reason.

Wollstonecraft was dismayed by the way in which women were overlooked in the new calls for equality. She addressed A Vindication of the Rights of Woman to those directing the French Revolution and protested the effective denial of citizenship to women by the new French Constitution. What is a Revolution’s claim to equality based on, she asked, if it failed to recognize half of its population as rational human beings?

Her treatise is a wide-ranging piece of social, political and philosophical analysis on the situation of women in society. Responding to those who suggested that women should not seek to exercise rights and political functions, Wollstonecraft agrees that women have been rendered “artificial, weak creatures,” and even “useless members of society.” However, she argues that this is the result of a “false system of education”, women being given no opportunity to “unfold their faculties,” instead being trained to be playthings for men (Works 5: 91, 73-74). Wollstonecraft argues her points through a series of close readings of texts ranging from Milton and Rousseau to contemporary works on education, making her Rights of Woman not only a feminist political treatise, but also a work of moral philosophy and a founding work of feminist literary criticism. Wollstonecraft’s feminist argument is developed in critical dialogue with Rousseau’s Emile. She attacks his claim that girls and boys should be educated in accordance with different standards for moral perfectibility and argues that in order to be moral creatures both sexes must achieve the same virtues. Wollstonecraft concedes that women and men may have different duties in society, but she adds that these duties “are human duties, and the principles that should regulate the discharge of them […] must be the same” (Works 5: 120).

Wollstonecraft’s third, less well-known, political work is her An Historical and Moral View of the Origin and Progress of the French Revolution (1794). In this work, she justifies the Revolution and approves of its early stage; however, though she does not explicitly criticize the 1793 terror, some aspects of her account can be read as an implicit criticism of the later stages of the Revolution. Writing this book while she was living in Revolutionary France was a dangerous enterprise.

Wollstonecraft also wrote two novels, Mary; A Fiction (1788) and The Wrongs of Woman: Or, Maria. A Fragment (1798), the second of which is unfinished and published posthumously. While reason is the key tenet of her treatises, and the argument that women’s liberation will come from women becoming able to think for themselves, her novels engage with complex, nuanced questions around feeling and emotion. Mary; A Fiction is a work of what would now be described as “autofiction”, closely following the events of Wollstonecraft’s own early life. In her later, post-Revolutionary novel, The Wrongs of Woman, Wollstonecraft places her hopes for social change in people using their personal struggles as a way into a wider understanding of the world, and in particular in women sympathizing with other women. Her novel’s heroine, Maria, who is locked up after confronting her husband with his attempt to prostitute her, finds that her pain “led me out of myself, to expatiate on the misery peculiar to my sex” (Works 1: 122). Similarly, Jemima, Maria’s prison-guard and working-class counterpart, tells of how, “The anguish which was now pent up in my bosom, seemed to open a new world to me: I began to extend my thoughts beyond myself, and grieve for human misery” (Works 1: 110). The move toward collective experience in The Wrongs of Woman finally forms the socializing bond by which both Maria and Jemima escape the highly symbolic madhouse and begin to a make a new life together—a life founded on a quite different understanding of the world than that developed from the flawed politics and sentimental romantic reveries of the madhouse itself.

Demonstrating immense generic versatility, Wollstonecraft also published an epistolary travel book, Letters written during a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark (1796). This work is perhaps her literary masterpiece, blending the social analysis of her treatises with the analysis of the role of emotion and affect in personal and public life. The work is based on a journey Wollstonecraft made in 1795 with her first daughter, Fanny, then just one year old. She was traveling in search of a lost shipment of silver belonging to Gilbert Imlay. The book is written as a series of letters to an unnamed lover who has proved unfaithful. It is an important work in the history of travel writing.

Finally, between 1787 and 1797 Wollstonecraft published hundreds of reviews of books of poetry, political pamphlets, histories, novels, and travel books in Johnson’s Analytical Review, where she also worked as an editorial assistant. The review was a new form in this period, and Wollstonecraft was at the forefront of helping to shape this new critical idiom. Among her most important reviews is a detailed discussion of Catharine Macaulay’s Letters on Education (1790). This review helps us trace Macaulay’s influence on Wollstonecraft’s thought and particularly on her transition from a general emphasis on the liberty and rights of men, expressed in Rights of Men, towards a specific defense of the liberty and rights of women developed in her latter Vindication.

System of thought: Wollstonecraft’s religious, philosophical and political thought combined elements from different traditions and authors. On the one hand, she was influenced by Richard Price and the Rational Dissenters, who emphasized that the independent use of reason forms a basis for moral and political agency. On the other hand she was, despite her criticisms of his views on women, influenced by Rousseau’s emphasis on the important roles the passions and imagination play in human life. Combining these elements she builds a system of her own, which emphasizes both reason and passions as parts of a dignified life. Wollstonecraft uses Price’s understanding of the unity of virtue based on reason in order to criticize Rousseau’s idea about separate and complementary male and female virtues, but simultaneously Rousseau and other sentimentalist authors inspired her to develop a moral theory where the passions play a much more crucial role than they do in Price’s purely rationalist theory. A third important influence was Catharine Macaulay (1731-1791) and particularly her book Letters on Education. In her criticism of Rousseau’s views on women, Macaulay uses arguments that are quite similar to those that Wollstonecraft develops in Rights of Woman. Macaulay’s discussion of Rousseau is brief, though, and Wollstonecraft spells out the arguments in more detail.

Wollstonecraft’s political thought emphasizes liberty as the freedom from arbitrary – meaning lawless and unjustified – power and her thought is often seen as part of the republican political tradition (e.g. Halldenius 2015; Coffee 2014). She shares many of her political ideas with Price, Rousseau and Macaulay, among others, but she is unique among her contemporaries in her radical analysis of how women are subjected to the arbitrary power of men. According to Wollstonecraft, the same freedom from arbitrary rule must be guaranteed in marriage as well as in the state, where it must be granted on equal terms to both women and men.

Reputation

Wollstonecraft was respected in her own circle, but was publicly vilified by conservative commentators during her lifetime and after her death, her political opinions leading her to be labelled a woman whom “far outsteps her proper sphere” (British Critic 7, Jump 142). Shortly after she died, her husband William Godwin published both her private letters to Gilbert Imlay and an intimate memoir of her life, Memoirs of the Author of a Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1798). Godwin’s frankness about Wollstonecraft’s relationship with Imlay appalled many of his contemporaries, and the resulting scandal contributed to neglect of her work for much of the next century. Even before the memoir, those sympathetic to some of her arguments were troubled by revelations about her personal life, with poet Anna Seward writing, for example, “If her system could not steel her own heart, as it seeks to fortify that of her sex in general, we should at least have expected her to conceal the weakness, whose disclosure evinced the incompetence of her maxim” (Seward 5:48).

Even during the period in which she was only read and admired in small circles, however, these were influential ones. Her posthumously published essay, “On Poetry, and Our Relish for the Beauties of Nature” (1797) influenced William Wordsworth’s conceptions of the imagination in his Preface to Lyrical Ballads (1800), perhaps the most canonical statement of Romanticism. Her daughter Mary Shelley’s still phenomenally popular novel, Frankenstein, is deeply engaged with the debates about education, reason, and emotion developed by her mother.

Wollstonecraft reappears as an early feminist role model in the 1890s, when the centenary of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman gave the occasion to publish new editions, many of them with introductions by women activists, such as the British suffragist Millicent Fawcett (1847-1929). These new editions were followed by some early scholarship on Wollstonecraft, such as A Study of Mary Wollstonecraft and the Rights of Woman (1898), by Emma Rauschenbusch-Clough (1859-1940), who had received her PhD at the University of Bern. (Botting & Cronin 2014) The exact extent of Wollstonecraft’s influence on the women’s movements of the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-centuries is still hard to assess, but we can find interesting examples, which suggest a wide scope. For example, in 1895 a new periodical published by the women’s movement in Finland, at that point a part of the Russian Empire, referred to Wollstonecraft and her “brave conclusion” about all women being born free in its declaration titled “What we want” (Dahlberg 2018: 217).

It was through Godwin’s biography, however, as much as through her Vindications, that Wollstonecraft was encountered by some early twentieth-century feminists such as Emma Goldman and Virginia Woolf, who were fascinated by her life – or by what Woolf calls her “experiment” with living. As Cora Kaplan comments, for them “Wollstonecraft’s life is the more enduring and interesting text” (2002: 249).

In the final decades of the twentieth century, and the first decades of the twenty-first, attention turned to closer examinations of Wollstonecraft’s actual texts, including her novels and A Short Residence alongside the Vindications. Her works have become increasingly important in the fields of literary studies, intellectual history, political theory and philosophy. Wollstonecraft’s on-going contribution has come to be seen to extend beyond placing “women’s rights and sexual difference at the center of social and political debates,” to explorations of the complicated role emotion plays in private and public life (Kaplan 2002: 247). Recent work has drawn attention to the emphasis Wollstonecraft places, especially in her later writings, on trial and error, imagination, sensibility, and feeling, and to the vital role these play in her utopian brand of “world-transformative” politics (Taylor 2003: 2). The willingness to value emotional response evident in Wollstonecraft’s writings, in particular in her novels and travel writing, has come to seem deeply embedded in her wide-ranging contribution.

In 2011 Wollstonecraft became the center of a campaign calling for public memorials of women in London, where more than 90% of public sculptures commemorate men. In 2018, British artist Maggie Hambling was selected to make a permanent statue of Wollstonecraft that will be erected in Newington Green. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/may/16/maggi-hambling-picked-to-create-mary-wollstonecraft-statue

less

Bibliography

Primary sources:

Jump, Harriet Devine (2003) Mary Wollstonecraft and the Critics, 1788-2001. 2 vols. London: Routledge, 2003.

Wollstonecraft, Mary (1989) The Works of Mary Wollstonecraft, vols. 1-7, eds. Janet Todd and Marilyn Butler, with Emma Rees-Mogg. London: William Pickering.

Wollstonecraft, Mary (2004) Collected Letters, ed. Janet Todd. London: Penguin.

Secondary sources:

Botting, Eileen Hunt & Madeline Ahmed Cronin (2014) A Vindication of the Rights of Woman within the Women’s Human Rights Tradition, 1739-2015. In A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, ed. Eileen Hunt Botting. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 315-321.

Coffee, Alan (2014) Freedom as Independence: Mary Wollstonecraft and the Grand Blessing of Life. Hypatia 29 (4): 908-924.

Dahlberg, Julia (2018) Konstnär, kvinna medborgare: Helena Westermarck och den finska bildningskulturen i det moderna genombrottets tid 1880–1910 [Artist, Woman, Citizen: Helena Westermarck and Finnish Bildung at the Outbreak of Modernity 1880-1910]. Helsinki: Finska Vetenskaps-Societeten.

Halldenius, Lena (2015) Mary Wollstonecraft and Feminist Republicanism. London: Pickering & Chatto.

Kaplan, Cora (2002) Mary Wollstonecraft’s Reception and Legacies. In The Cambridge Companion to Mary Wollstonecraft, ed. Claudia L. Johnson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 246-70.

Seward, Anna. Letters of Anna Seward, edited by Archibald Constable. 6 vols. Edinburgh, 1811.

Taylor, Barbara (2003) Mary Wollstonecraft and the Feminist Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully