Birth

May 4, 1759

Education

Unknown

Death

February 19, 1843

Religion

UnitarianMary Hays was a novelist well-known for her belief in radical feminism and her proactive history of women: Female Biography. Born in 1759, Hays was a rarity for her time, leaving her family to live in London and work as a professional writer and researcher. She wrote many works over the course of her life, and she fiercely defended feminist ideals: including women’s education, women’s social and economic independence, and equality among the sexes in matters of intellectual, social, and religious expression. Hays desired to teach and mentor young women.

In her lifetime, she published poetry, short tales, moral and philosophical essays, religious tracts, periodical essays on various subjects, book reviews, sentimental and romantic fiction, a treatise on women’s rights and education, women’s biographies and life writing, children’s literature, historical literature for young readers, and moral and didactic fiction and drama.

Personal Information

Name(s)

Mary Hays

Date and place of birth

May 4, 1759, along Shad Thames, in Southwark, where her father worked from the wharves as a mariner and ship’s captain and later as a corn factor in close connection with the Dunkin family. The Hayses first appear in the Poor Rate Books on Shad Thames in 1768; in 1776 Mrs. Hays appears at 5 Gainsford Street, Southwark.

Date and place of death

Sunday, February 19, 1843, at Miss Farrell’s boarding house in Lower Clapton, near Homerton, London; buried at Abney Park Cemetery, Stoke Newington, on 25 February 1843; her will is dated 18 October 1840, with a codicil dated 13 February 1843, just days before her death (see National Archives, PROB 11/1076).

Family

Mother: Elizabeth Judge Hays (c. 1730-1812); after her husband’s death in 1774, she maintained a wine business from her Gainsford Street home for many years; her will proved January 28, 1813 (see National Archives, PROB 11/1540/448), leaving Mary and her sister, Elizabeth, each about £8000.

Father: John Hays (October 13, 1729-April 1774), St. Thomas’s Chapel (Presbyterian), Southwark; primarily a ship’s captain, but may have worked in various occupations along the wharves of the Thames, including as a corn factor (see National Archives, PROB 11/997).

Marriage and Family Life

Mary Hays never married; she lived with her family in Gainsford Street until 1795, after which she lived independently (1795-1809), or with her two brothers (1809-13, 1832-41), or as a boarder in a larger establishment. She was devoted to her sisters and brothers—Joanna Hays Dunkin (1754-1805), Sarah Hays Hills (c. 1755-1836), Elizabeth Hays Lanfear (1765/66-1825), Marianna Hays Palmer (1773-1797), John Hays (1768-1862), and Thomas Hays (1772-1856)—as well as more than forty nieces and nephews, some of whom she lived with and tutored in her later years; except for 1813-16, she always lived in Greater London and within close proximity of her relations.

Education

Nothing is known of her education other than the fact that the breadth of knowledge evidenced in her letters to John Eccles in her late teens indicates she either had some formal schooling or was simply an avid reader and brilliant autodidact.

Religion

Raised a Particular Baptist in the Gainsford Street Chapel, Blackfields, Hays became a “Rational Dissenter” (Unitarian) by the early 1790s and remained so thereafter. She may not have attended a particular congregation regularly after joining Salters’ Hall in 1792; it seems likely, however, that when she lived in Islington she attended the Presbyterian (Unitarian) congregation at Stoke Newington or the General Baptist (Unitarian) congregation at Worship Street led by her friend and former correspondent, John Evans.

Transformation(s)

One significant transformation was her movement, with her sister Elizabeth, from the Calvinism of the Particular Baptists in which she was raised to Unitarianism by the early 1790s. Another was Hays’s shift from sentimental fiction in the 1790s to the relatively new but emerging fields of women’s biography, historical works and novels for young readers, and moral and didactic conduct literature, the latter occurring as a result of her public involvement with such social and philanthropic enterprises as the Prudent Man’s Friend Society and Savings Bank during her time in Bristol. Lastly, her radical decision to leave her family in Southwark and live as an independent woman and professional writer and researcher in London, Camberwell, and Islington between 1795 and 1809 was a feat duplicated by few women of the time.

Contemporaneous Network(s)

Her main networks were active in the 1790s. One involved numerous London Unitarian ministers, such as Lindsey, Priestley, Evans, Disney, Worthington; and laymen, such as William Frend, George Dyer, Anthony Robinson, and Crabb Robinson; another involved the Godwin-Wollstonecraft circle of radical writers in the 1790s, which included Eliza Fenwick, Mary Robinson, Charlotte Smith, Amelia Alderson, and later Henry Crabb Robinson. In Bristol c. 1815-17 she interacted with a network of creative and socially active women involved in the founding of the Prudent Man’s Friend Society, for which Hays served as a member of the women’s committee in 1815 and 1816 and published her didactic work The Brothers for the benefit of the Society.

less

Significance

Works/Agency

1784-86. Poems and short moral tales in the Universal Magazine.

“Cursory Remarks on an Enquiry into the Expediency and Propriety of Public or Social Worship”: inscribed to Gilbert Wakefield, B.A., late fellow of Jesus-College, Cambridge. London: T. Knott, No. 47 Lombard Street, 1792.

Letters and Essays, Moral, and Miscellaneous. London: T. Knott, 1793.

1796-1801. Various articles by Hays in the Monthly Magazine and a few in the Analytical Review.

Memoirs of Emma Courtney. London: G. G. & J. Robinson, Paternoster Row, 1796.

Appeal to the Men of Great Britain. London: J. Johnson; and J. Bell, 1798.

The Victim of Prejudice. London: J. Johnson, 1799.

“Wollstonecraft.” Annual Necrology for 1797-98. London: R. Phillips, 1800. 411-60.

“Life of Charlotte Smith.” Public Characters of 1800-01. London: R. Phillips, 1801. 42-64.

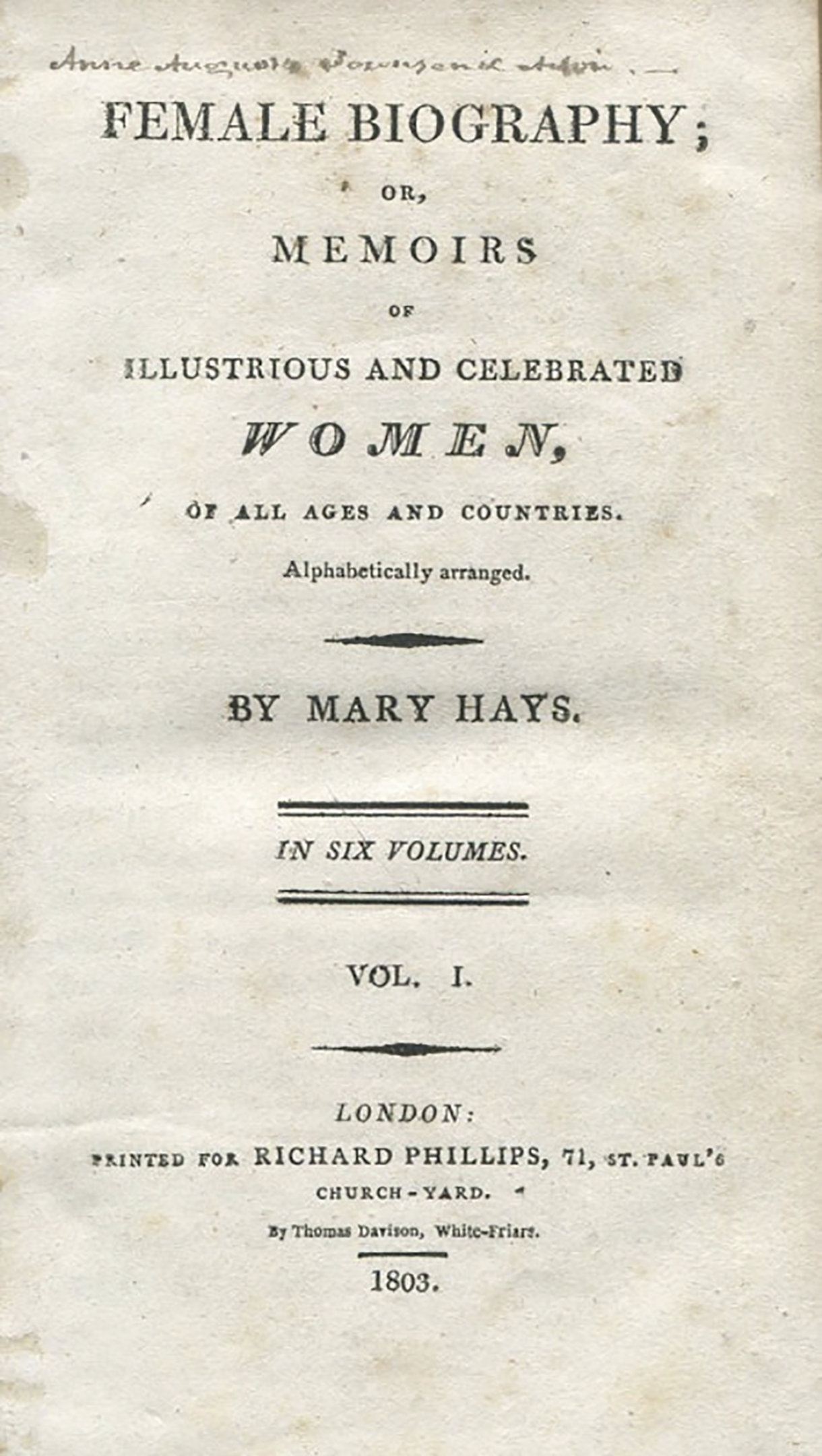

Female Biography. 6 vols. London: R. Phillips, 1803.

Harry Clinton; or, a Tale of Youth. London: J. Johnson, 1804.

The History of England ... in a Series of Letters to a Young Lady at School (Charlotte Smith, of which Hays wrote much of volume 2 and all of volume 3). London: R. Phillips, 1806.

Historical Dialogues for Young Persons. 3 vols. London: Printed for J. Johnson, St. Paul’s Churchyard; and J. Mawman, Poultry, 1806-1808.

The Brothers; or, Consequences: A Story of What Happens Every Day; Addressed to that Most Useful Part of the Community, the Labouring Poor. London: Button and Son, 1815.

Family Annals, or The Sisters. London: Printed for W. Simpkin and R. Marshall, Stationers’ Court, Ludgate Street, 1817. Title page notes: “Author of the Brothers, Female Biography, Historical Dialogues for Young persons, Harry Clinton, a Tale for Youth, &c. &c.”

Memoirs of Queens: Illustrious and Celebrated. London: T. and J. Allman, Booksellers to Her Majesty, Prince’s Street, Hanover-Square. 1821.

Contemporaneous Identifications

Other than the harsh comments on her in Richard Polwhele’s poem “The Unsex’d Females” (1798), no significant references to Hays appeared during her lifetime in other works about women.

Reputation

Though viewed as a powerful theological thinker among Unitarians in early- to mid-1790s, by 1798 she had become tainted as a Jacobin writer and follower of Godwin and falsely accused of holding loose moral convictions. She developed a reputation after 1800 as a writer of women’s biographies and historical and moral works for young and working-class readers. Though influenced by sentimental fiction in her youth (as evidenced in her correspondence with John Eccles), by the 1790s she was espousing feminist ideals concerning women’s education and women’s social and economic independence, as well as equality among the sexes in matters of intellectual, social, and religious expression. Though largely ignored during the 19th century and damaged in reputation by early biographical works by her great-niece, Anne F. Wedd, Hays is now viewed as a major woman writer and, like her friend Wollstonecraft, a powerful feminist voice. She is also important for her role as an advocate of religious Dissent (both as a Baptist and Unitarian) and her determination to live as an independent woman, juggling professional duties and domestic loyalties for nearly fifty years.

Legacy and Influence

Mary Hays is an important figure within the Godwin-Wollstonecraft circle in the 1790s, sharing with her sister Elizabeth Hays Lanfear the distinction of being the first two women novelists in England to have been immersed from birth in the culture of religious Dissent. Memoirs of Emma Courtney resides at the forefront of early feminist novels and cautionary tales about the consequences of decisions made and situations endured by women in matters of love and marriage, decisions that too often left them bound to a state of financial dependence and social isolation. Her work as a promoter of women’s biography, both contemporary and historical, has been enhanced with the recent republication of Hays’s important multi-volume work, Female Biography. Between 1784 and 1821, Hays published poetry, short oriental tales, moral and philosophical essays, religious tracts, periodical essays on various subjects, book reviews, sentimental and romantic fiction, a treatise on women’s rights and education, women’s biographies and life writing, children’s literature, historical literature for young readers, and moral and didactic fiction and drama. Her legacy as a prominent figure within the genre of didactic and moral literature for young readers has yet to be fully developed. She demonstrated an active pursuit of knowledge, a consistent allegiance to the principles of religious Dissent, a persistent loyalty to family and friends, and a desire to teach and, more importantly, mentor young women (such as her youngest niece, Matilda Mary Hays) into becoming well-read, independent, self-reliant individuals.

less

Controversies

Controversy

Her membership within the Godwin circle and her novel Emma Courtney led to her inclusion in Powhele’s “Unsex’d Females” (1798). False accusations of improper sexual conduct by Charles Lloyd in 1798 further damaged her public persona and left a stain upon her character that continued into the 20th century. In Emma Courtney and The Victim of Prejudice, as well as her biographies of famous women, Hays exposed the inadequacies of women’s education and domestic roles, the unfair rules of decorum for women in courtship and marriage, the plight of women facing marital infidelity, abuse, abandonment, and poverty, and the difficulties women faced in maintaining a state of independence, security, and happiness apart from the legal confines of marriage.

New and unfolding information and/or interpretations

Genealogical research has illuminated Hays’s literary, social, and domestic life, especially the wealth of her family, the uncovering of the identity of Hays’s youngest sister Marianna, and Hays’s intimate bonds with many of her nephews and nieces, especially Matilda Mary Hays. Renewed emphasis upon Hays’s Dissenting background is also yielding new interpretations of her historical and didactic works for young readers, her use of circulating and subscription libraries for source material, her place within various networks of women educators, writers, booksellers, and philanthropists (such as Eliza Fenwick, Mary Bryan, Mary Ann Starling Hookham, Susanna Morgan, and Marianne Schimmelpenninck).

less

Bibliography

Sources

Primary (selected):

Brooks, Marilyn, ed. Memoirs of Emma Courtney. Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press, 2000.

—, ed. The Correspondence (1779-1843) of Mary Hays, British Novelist. Lewiston, ME: Edwin Mellen Press, 2004.

Kell, E. “Memoir of Mary Hays: With Some Unpublished Letters addressed to her by Robert Robinson, of Cambridge, and Others.” Christian Reformer 11 (September 1844): 813-20.

Rajan, Tilottama. “Autonarration and Genotext in Mary Hays’ Memoirs of Emma Courtney.” Romanticism 32.2 (1993): 149-76.

Rogers, Katherine. “The Contribution of Mary Hays.” Prose Studies 10.2 (1987): 131-42.

Spongberg, Mary. “Mary Hays and Mary Wollstonecraft and the Evolution of Dissenting Feminism.” Enlightenment and Dissent 26 (2010): 230-58.

Ty, Eleanor. Unsex’d Revolutionaries: Five Women Novelists of the 1790s. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993.

—, ed. The Victim of Prejudice. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press, 1995.

Walker, Gina Luria, ed. The Idea of Being Free: A Mary Hays Reader. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press, 2006.

—, ed. Female Biography; or, Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women. 6 vols. Chawton House Library Edition. London: Pickering & Chatto, 2013-14.

—. Mary Hays (1759-1843): The Growth of a Woman’s Mind. Aldershot, Hampshire, UK: Ashgate, 2006.

—. “I sought and made myself an extraordinary destiny.” Women's Writing 25.2 (2018): 124-149.

Wedd, Anne F., ed. Love-Letters of Mary Hays (1779-1780). London: Methuen, 1925.

Whelan, Timothy. “Mary Hays and Henry Crabb Robinson.” The Wordsworth Circle 46.3 (2015): 176-90.

—. “Mary Hays and Dissenting Culture, 1770-1810.” The Wordsworth Circle 50.3 (2019): 318-47.

Archival resources (selected):

Mary Hays Collection (MH 0028), Carl H. Pforzheimer Collection of Shelley and His Circle, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

- F. Wedd Collection, shelfmark 24.93(12), Dr. Williams's Library, London.

Fenwick Family Correspondence, 1798-1855, MS 211, New York Historical Society, New York City.

Individual letters in the special collections at the University of Kentucky, the British Library, the Bodleian Library (Abinger Collection), and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania Library.

Web resources (selected):

Mary Hays: Life, Writings, and Correspondence, ed. Timothy Whelan, at www.maryhayslifewritingscorrespondence.com

Issues with the sources.

The letters to and from Mary Hays in the Pforzheimer Collection, the Fenwick Family Correspondence, and the A. F. Wedd Collection were initially in the possession of A. F. Wedd. Transcriptions of whole and partial letters appeared in Wedd’s The Love-Letters of Mary Hays (London: Methuen & Co., 1925) and The Fate of the Fenwicks (London: Methuen & Co., 1927). Unfortunately, Wedd excised nearly all comments by Mary Hays about her personal involvement with various family members and friends, as well as Hays’s more radical comments nature about love, religion, politics, and other areas of intellectual interest to Hays. These excisions have recently been made available to scholars in a new online edition of Hays’s correspondence. In a similar vein, Edith Morley, early 20th century editor of Henry Crabb Robinson’s Correspondence, Diary, and Reminiscences, included less than ten references by Robinson to Hays out of nearly 200 that appear in his massive body of manuscript life writings, inadvertently (or possibly by design) burying invaluable information and restricting scholars from reconstituting a complete biographical assessment of Hays for nearly a century.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully