Birth

Unknown

Death

August 30, 1848

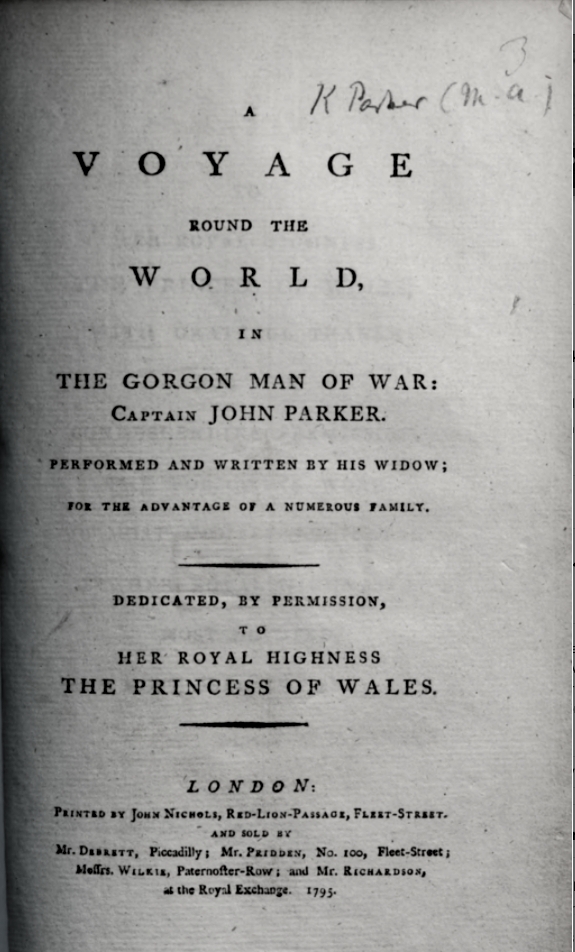

Mary Ann Parker was the first European woman to publish a travel memoir of her return voyage and visit to New South Wales on the continent now known as Australia. Her memoir, titled A Voyage round the world in the Gorgon man of war (1795), was written during the first years of Britain’s penal colony at Port Jackson. She received several donations from the Literary Fund for her work. No later published work has been identified by Mary Ann Parker.

Personal Information

Name(s)

Mary Ann Parker, born Mary Ann Burrows.

Date and place of birth

Not known.

Death and place of death

August 30, 1848, Connaught Terrace, London.

Family

The scholar Charlotte MacKenzie discovered that Mary Ann Parker’s parents were John and Mary Burrows. Her parents manufactured and distributed Velno’s vegetable syrup. This was from a French recipe for which they obtained a patent. John and Mary Burrows sought to capitalise on the market for the treatment of sexually transmitted infections, which were rife in Georgian London, with non-toxic alternatives to mercury. They also described their vegetable syrup as anti-scorbutic, meaning it may have been taken by mariners as a prophylactic or to treat scurvy. This approach was not dismissed by medical practitioners; Erasmus Darwin advised his patient, the writer Anna Seward, to take Velno’s Vegetable Syrup. John Burrows (bap. 1721) was a medical practitioner. He has been the focus of historical research; this research did not consider the role of Mary Burrows or identify his relationship to Mary Ann Parker. Mary Burrows may have worked on medical translations from the French published in her husband’s name.

From 1775 to 1782, Mary Ann Parker travelled in Europe with her parents and acquired knowledge of other European languages. In 1775, John Burrows accepted an offer of employment from John Sherratt, who had been appointed as the British Consul at Cartagena in Spain. The Burrows family travelled together to Spain with Sherratt’s household. They lived in Spain for four years, where John Burrows stayed and worked as a physician after Sherratt returned to Britain in 1777. It was here that the young Mary Ann Parker learned Spanish. As Britain’s conflicts with France and Spain escalated in the Mediterranean, the Burrows family were likely among those who left by ships for Italy, prior to the siege of Gibraltar. Travelling to Livorno and then inland, where they remained in Tuscany until the Autumn of 1782.

Mother: Mary Burrows, second wife of John Burrows. Mary Burrows was educated and worked alongside her husband. Mary Burrows was described with warmth by Mary Ann Parker as ‘An affectionate mother.’ Mary Ann Parker was her parents' only child.

Father: John Burrows (bap. 1721). It is unlikely that John Burrows’ first wife Sarah was the mother of Mary Ann, who may have been born before Sarah Burrows died age 51. John and Sarah Burrows had no known children. When Mary Ann Burrows married John Parker on January 29, 1783, she was identified by her “natural and lawful” father John Burrows as a minor, age sixteen or older (born before January 29, 1767). Mary Ann Parker was later identified as aged ‘82’ when she died on August 30, 1848 (born before August 30, 1766).

Marriage and Family Life

Mary Ann Burrows married John Parker, a Royal Navy officer, on Monday January 29, 1783, at St James Piccadilly, London.

The teenage Mary Ann Burrows may have met the Royal Navy midshipman John Parker (d. 1794) in Europe. Mary Ann Burrows was a minor when she married John Parker in London. In the month following their wedding John Parker was promoted Lieutenant.

By the time their first child was born two years later, John and Mary Ann Parker had established their own London home separately from her parents.

John Parker was Captain of HMS Gorgon when Mary Ann Parker accompanied him in 1791-1792. When their ship called at Tenerife on the outward voyage, Mary Ann Parker used her knowledge of Spanish as well as English to act as an interpreter.

John and Mary Ann Parker had five children. Mary Ann Parker’s fourth pregnancy was during her voyage on HMS Gorgon; her diet, health, and birth in London shortly after arriving home, were included in her account. This is information that may have been valued by women who were deciding whether or not to travel with their husbands in similar circumstances.

When Mary Ann Parker embarked on HMS Gorgon in February 1791, she left her children with her mother “with whom I had travelled into France, Italy and Spain; and from whom I had never been separated a fortnight at one time during the whole course of my life.” Their son John died while his parents were away.

Captain John Parker died of yellow fever, in Martinique, August 1794. Mary Ann Parker was a single parent after she was widowed in her twenties. Her mother Mary Burrows may have helped care for her grandchildren while John and Mary Ann Parker were travelling and after John Parker died. When A Voyage round the world was published, Mary Ann Parker was living at number 6 Little Chelsea. She received some prize money that had been awarded to her late husband, which she may have invested in this property, obtaining a home for herself and her children. Mary Ann Parker and her widowed mother later shared a single household. Mary Ann Parker did not marry again. She later lived with the family of her daughter Margaret Vincent.

Mary Ann and John Parker’s five children:

1785: Mary Ann Parker, born August 16, christened September 4, St Clement Danes, London. Died before 1791.

1786: Margaret Parker, born November 22, christened January 6, 1787, St Clement Danes, London. Married 1818 to Robert Vincent, a solicitor.

1789: John Henry George Parker, christened December 10, St Andrew, Holborn, London. Died in London while his parents were travelling in 1791-1792.

1792: Henry Edward Parker, christened July 18, St Anne, Soho, London. Died December 1798.

1794: Sarah Maria Parker, christened September 17, St Mary Abbots, Kensington, London.

Education (short version)

The arrangements made for Mary Ann Parker’s school or at home education are not known. As a child, Mary Ann Parker learned to read and write. Mary Ann Parker acquired knowledge of other languages while travelling in Europe with her parents from 1775 to 1782.

Religion

Her wedding, children’s christenings, and family burials were in Anglican churches in London.

Transformation(s)

The experience of being widowed and financially responsible for her family led Mary Ann Parker to write and publish A Voyage round the world in the Gorgon man of war (1795).

Many widows found that naval pensions did not adequately support the bereaved families of seamen. A call for subscriptions to Mary Ann Parker’s planned publication may have sat on the desks of navy pay offices, as well as the counters of some booksellers. Mary Ann Parker was the first woman to publish an account of New South Wales which was more than a letter in a newspaper.

The printing of A Voyage round the world in the Gorgon man of war (1795) was supported by over 200 sympathetic or expectant subscribers. The book was prefaced with an approved dedication to Caroline, Princess of Wales, dated June 25, 1795.

Mary Ann Parker’s book was published in the summer of 1795. In the book Mary Ann Parker described herself as writing with her right hand while holding her seven month old baby in her left arm. It has been suggested that Mary Ann Parker’s last child with her late husband was born in December 1794. However, Captain John Parker of HMS Woolwich left for the West Indies before the end of 1793. If Mary Ann Parker’s daughter was born in the Summer of 1794, her comment on the age of her youngest child would mean that she was writing her book in the Spring of 1795, which fits with the dates of dedication and publication. This also fits with the christening of their daughter Sarah Maria Parker on September 17, 1794.

Contemporaneous Identifications

A year after A voyage round the world in the Gorgon man of war was published, Mary Ann Parker received her first donation from the Literary Fund. There is no extant application for the first donation. The five guineas granted to Mary Ann Parker was agreed by the Committee on March 17, 1796, to whom representations had been made that “she is at present in great distress.” Two years later the second application was made on Mary Ann Parker’s behalf. The application was made by Francis Stephens, after he had received a letter from the vicar of St. Luke’s in Chelsea, Reverend Charles Sturges. Three years after Mary Ann Parker’s book had been published, Sturges emphasised her family and domestic obligations, not the merits of her book or future intentions as a writer. On May 17, 1798, the Literary Fund Committee agreed a second donation of five guineas. By May 1799, Mary Ann Parker was once again in financial need and applied directly to the Literary Fund, whose Committee again agreed a donation of five guineas. On this occasion Mary Ann Parker mentioned that she, her daughters, and her widowed mother were sharing the same household.

By 1804, if not before, Mary Ann Parker had moved her family to a less prosperous district in central London. She was living with her two “poor girls” at 30 Wych Street, Drury Lane. Margaret Parker was by then age seventeen, possibly in employment, and able to provide some of the everyday care for Mary Ann Parker’s youngest daughter. In her application at that time to the Literary Fund, she explained that she was “Confined for debt … within the Gloomy Walls of a prison”; and that “her children will this week be oblig’d to quit their home with the loss of that property which has enabled us hitherto to find support.” This letter included the addresses of two shops where donations could be made. It was in this letter that Mary Ann Parker mentioned that she was a physician’s daughter, her distressed circumstances possibly causing her to recall the bankruptcy her father experienced. The Literary Fund Committee once again agreed to a donation of five guineas. Mary Ann Parker’s letter of thanks to the Committee was sent from ‘Number 1, 3rd gallery, Fleet’ prison, a debtors’ prison; it was a despairing communication which revealed, despite their donation, “I have little if any hope of once more living with my poor girls outside this horrid abode.” After Mary Ann Parker was discharged from Fleet prison two months later, her next whereabouts and occupation are not known. Mary Ann Parker later lived with the family of her married daughter Margaret Vincent. Mary Ann Parker was described as 82 years old when she died in 1848.

Contemporaneous Network(s)

Mary Ann Parker wrote about conversations between women and men, in social groups, and individually. This included her conversations with Bennelong of the Eora people in her home in London.

Mary Ann Parker presented herself as having and valuing human empathy. Nonetheless she is not known to have been a participant in organisations or causes.

Mary Ann Parker received four donations from the Literary Fund. These came from the patronage of male friends and acquaintances. That might be taken as evidence that Mary Ann Parker was willing to network and conduct transactional relationships.

less

Significance

Works/Agency

As a woman’s narrative written during the first years of Britain’s penal colony at Port Jackson, New South Wales, and about the related voyages and transportation, A Voyage round the world in the Gorgon man of war (1795) is unique.

Reputation

In 1806, the Literary Fund completed an internal investigation to review its previous donations, which concluded “that the claims of 74 Persons appeared to be of so questionable a nature that they ought, on any future application, to be referred to a Committee of Inquiry.” “Among these was the name of Mrs. Mary Ann Parker,” who had received a total of 20 guineas from the Literary Fund in 1796-1804. The number of donations queried confirmed that it was the Committee’s decisions in relation to the Fund’s purposes that were being reconsidered. Nonetheless, it highlighted that after publishing her travel book Mary Ann Parker had not published other work in her name.

Legacy and Influence

Mary Ann Parker’s legacy was A Voyage Round the World in the Gorgon Man of War (1795) and related historical scholarship.

less

Controversies

Controversy

In her lifetime, Mary Ann Parker did not engage in or provoke controversy. There were public and private controversies in her father’s life, which Mary Ann Parker may have consciously chosen to make efforts to avoid. She obtained subscribers and a royal endorsement before she published her book.

New and Unfolding Information and/or Interpretations

The identification in 2022 of Mary Ann Parker’s parents brings together the scholarship about her writing and biography with studies of her father’s career, conduct, and travels as a medical practitioner.

less

Bibliography

Primary (selected):

MacKenzie, Charlotte. 2022. The travel writer Mary Ann Parker.

Parker, Mary Ann. 1795. A voyage round the world in the Gorgon man of war.

Archival Resources (selected):

Most of the archives related to the voyage of HMS Gorgon are digitised online and can be accessed free through Trove. https://trove.nla.gov.au/search/category/correspondence?keyword=Gorgon

Web Resources (selected):

https://blogs.bl.uk/untoldlives/2022/03/the-travel-writer-mary-ann-parker-1.html

Issues with the Sources

Mary Ann Parker was a European woman married to a Royal Navy Captain who was charged to carry passengers and supplies associated with the first years of Britain’s penal colony at Port Jackson, New South Wales, in 1791 and 1792. Her book was published with an approved dedication to Caroline, Princess of Wales. Other than through her descriptions of the voyage and her visit to the penal colony, Mary Ann Parker did not comment on national policy or British colonialism. In her book she did not question the cultural, social, and economic relationships she encountered. Mary Ann Parker was not a cultural relativist. Nonetheless, she presented herself as empathic towards individuals whatever their cultural background.

With the exception of Charlotte MacKenzie’s work, the historical research and writing about Mary Ann Parker and John Burrows before 2022 was compartmentalised by the fact that their relationship had not been identified by historians.

The historical archives are held in locations dispersed across the globe. The free to use online digital access through Trove is invaluable for researchers.

Images

The available images from Mary Ann Parker’s life are of documents, some of which she signed, and A voyage round the world in the Gorgon man of war (1795).

Comment

Your message was sent successfully