Birth

March 17th, 1754 in Quai de l'Horloge, 75001 Paris, FranceDeath

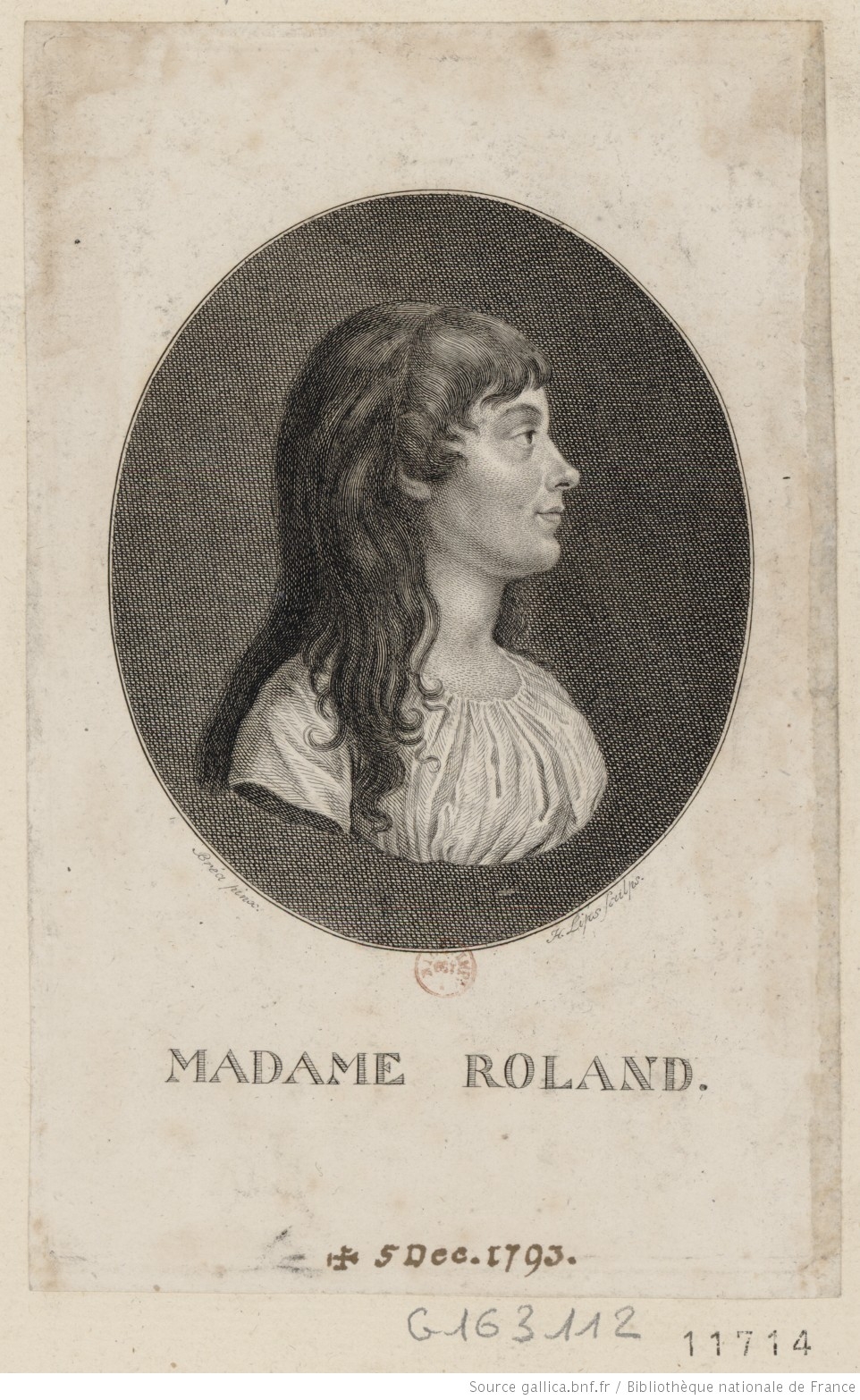

November 8th, 1793Marie-Jeanne Phlipon Roland was a French Revolutionary and writer. She was highly influenced by reading Plutarch, Rousseau, and Macauly. In her writings, she covered issues of philosophy and politics, as well as pregnancy, childbirth, and nursing. She was arrested at a Jacobin inspired insurrection that ultimately led her to the guillotine. Roland’s main works were her Memoirs, written in prison in the months before she died.

Personal Information

Name(s)

Marie-Jeanne (Manon) Phlipon Roland AKA Madame Roland.

Date and place of birth

Born 17 March 1754 in Paris, Quai de l’Horloge.

Date and place of death

Guillotined 8 November 1793, in Paris, Place de la Revolution (Place de la Concorde).

Family

Marie-Jeanne’s mother Marie-Marguerite Bimont (1723-1775) came from a family of high class artisans. Her father, Pierre-Gassien Phlipon (1724-1789) was the son of a wine seller and had gone up in life by taking up the trade of engraver.

Marie-Jeanne’s maternal grandmother, Marie-Marguerite Trude’s family had been glassmakers to the aristocracy while her maternal grandfather had been a haberdasher. Her paternal grandmother, Marie-Genevieve Rotisset, although, like her husband, she came from a family of wine sellers, had been employed as a lady of company for the aristocratic Madame Boismorel and was as a result more genteel and better connected than her son.

Marriage and Family Life

Marie-Jeanne married Jean-Marie Roland de la Platière, a younger son from the minor branch of an aristocratic family, after a four year long courtship, in 1780. She had had a number of offers (up to twenty documented ones!) but turned down each one because she had not enough in common with them. Roland was introduced to her by her best friends, the Cannet sisters. They corresponded and a year later they were secretly engaged – Roland’s family objected to his marrying into an artisan’s family.

Their only child Eudora was born in 1781. Marie-Jeanne wrote an account of her pregnancy and of breastfeeding her daughter, which was published after her death (Champagneux). Both she and Roland were involved in every aspect of her education, puzzling together about what to do when Marie-Jeanne’s milk seemed to dry up, and preparing an educational program inspired by Rousseau when she was older. Eudora was thirteen when her parents died. She was first under the guardianship of a young family friend, Bosc, but when they fell in love, she transferred her guardianship of Champagneux, the first editor of Marie-Jeanne’s works. At fifteen she was married to Champagneux’s son. She died in 1858.

Education

Manon read books she found in her home from a very young age. Her parents, finding her to be intelligent, employed various tutors. At the age of 12 she spends a year at the home of her grandmother and great aunt Angelique on the Ile Saint Louis. She reads theological books, and discovers Bossuet ‘a new food to my mind’. There she is introduced to the Boismorel family and takes note of the way Monsieur de Boismorel educates his son. She made philosophical friends through her tutors and her father’s customers, and they sent her books. By the time she met Roland, she was extremely well read, knew Latin and English, and well informed about politics.

Religion

Her early childhood was not particularly pious: she enjoyed showing her learning off at catechism, but soon realized there more interesting things to read than the lives of the saints and, age nine, hid Plutarch’s Lives in the cover of her prayer book.

When she was 10 an apprentice of her father’s sexually assaulted her, twice. She told her mother the second time, and her mother’s use of shaming brought about a bout of extreme piety. She asked to spend the following year at the convent school of Notre Dame de la Congregation in Paris. There she was a favourite with the nuns, and made life long friends, and for a while became deeply religious.

Shortly after she came back from Convent school, in her early teens, she lost her faith and became a confirmed atheist republican, which she remained until her death.

Transformation(s)

Roland’s main work is her Memoirs, written in prison in the months before she died, and it is quite clear from them what the events that triggered her transformations were. All save one were books.

The first was her reading of Plutarch’s Lives, at the age of nine (possibly Madame D’Acier’s translation) which, by her account, first prompted her to become a republican. It also led her to wish that she had been born a man, so that she could participate in the fight against tyranny. Then, in her early twenties, she discovered the one book by Rousseau that she had not previously read: Julie or the New Heloise. This led her to realise that she could contribute to the regeneration of society without being a man, provide she was married and with a family. Until 1789, she tried as best she could to emulate Rousseau’s family-based republicanism, but when the revolution happened, she had a change of heart and decided that it was no longer enough to care for her family: she had to participate, she had to act. Her last transformation occurred in the last weeks of her life. She had begun to read Catherine Macaulay’s History of England and was inspired to wish that if she did not die, she too would become a republican historian, and write about the revolution. She also decided gave up her long-held beliefs that it was better for women who wrote to publish – if they must - anonymously. Like Macaulay, she felt she had the authority to publish in her own name, and if she lived, she would.

Contemporaneous Network(s)

Marie-Jeanne Roland belonged to the circle of the Girondins, or Brissotins, as they were sometimes called, with her husband, minister of the interior, Brissot, Lanthenas, Etienne Clavière, Barberoux, Bancal, Buzot and Dumouriez. She is sometimes referred to as their Egeria. She admits to advising members of the government or Assembly as to what they should do or say, and to writing a number of her husband’s letters while he was at the ministry.

Her salon did not admit women: this was not because she did not think women were capable of contributing to the political dialogues – she was on good terms with a number of politically influential women including Madame Pétion, the wife of the Paris Mayor, and Felicité Brissot, as well as the English salonnière Helen Maria Williams. But she objected to members of the government such as Danton, or Girondins such as Dumouriez, who came to her salon, bringing prostitutes with them, and turning what she meant to be a serious political meeting into a debauched party. For similar reasons she served only sugar and water – never alcohol.

During the meetings she would seat silently at a side table, embroidering. Afterwards, she would receive those who had been present in the meeting in her office, and advise them.

less

Significance

Works/Agency

Manon Roland was a republican thinker who favoured a Rousseau style rural republicanism. That is, she thought that the republic, once declared, would be best consolidated with families living a virtuous and simple life and working the land. Her favourite model was Sparta, although she felt that the practice of slavery meant that it ultimately failed. She also followed Rousseau in claiming that a well-ordered family life was necessary for the growth of public virtue. But she was more ambivalent than he was on the question of gender, and was more inclined to distribute family and public work to both men and women.

Marie-Jeanne Roland wrote throughout her childhood – letters to her convent friends, Sophie and Henriette Cannet, and filling, she tells us, notebook after notebook. In 1776, she started to produce sustained philosophical works, essays that were published after her death by Champagneux. In 1777, she wrote an essay for a competition by the Academy of Besancon on the question “How can educating women help improve men?” She did not win a prise, but got a honourable mention.

Between 1780 and 1789, Manon worked with her husband who was producing an encyclopaedia of textile manufacturer for the publisher Pancoucke. She discovered that she was a better writer than she, and got into the habit of rewriting the texts he gave her to revise. During that time she also wrote travel books – about Switzerland, and about England – and a text about pregnancy, childbirth and nursing. All were published after her death. After the revolution her correspondence with friends, especially Brissot, took on a more political turn. Brissot published several of her letters, anonymously, in his journal, Le Patriote François.

Her most famous texts are those she wrote in prison, her Private Memoires, and Historical Notices. These, along with her correspondence, have been published many times.

Contemporaneous Identifications

Reputation

Marie-Jeanne Roland took care, throughout her lifetime, not to build a reputation other than for her womanly virtues. She worried that acquiring a reputation as an author would harm both her family, and later the revolutionary effort. She saw that women whose names became public were very often turned to ridicule, or accuse of not having written the works they signed themselves. And she noted that women who hosted salons in the early days of the revolution were often accused of seducing men into acting, and she felt that this was harmful to the cause. For that reason she insisted that whatever she wrote remain either unpublished or was published anonymously or under someone else’s name.

She received posthumous fame in the years after her death and throughout the nineteenth century, as a martyr of the revolution. Her Memoirs were printed several times, and sold well, as they contained much historical details about some central events of the revolution – the massacres of 10 August and 2 September 1792, for instance, as well as psychological portraits of some of its main actors – such as Danton, Robespierre and Brissot. She is no longer widely read. A recent mass-market book on the French Revolution barely mentions her, and only to claim (falsely) that she influenced the Girondists by seducing them.

Legacy and Influence

Sadly many of those that would have helped build her legacy died shortly after she did. Her husband killed himself with a sword the day after her execution. Her lover, Buzot, did the same as soon as he heard, a few weeks later. Other members of the Gironde were either executed or committed suicide with a few weeks of her death. Friends who were less involved in politics, and whom she knew from the botanical research she had conducted on behalf of her husband when he was writing his encyclopaedia of textiles took charge of her posterity. Both Bosc and Champagneux became guardians of her daughter Eudora. Bosc nearly married her, when she was only 13, and Champagneux married her to his son when she turned 15. Bosc and Champagneux fared better with her writings, publishing not only her memoirs, but her letters, and her earlier writings, attempting to show the world that they had lost, not only a talented politician, but a writer of some philosophical and literary importance. Unfortunately, the world chose not to see this and she became more obscure as time passed.

less

Controversies

Controversy

Roland’s enemy, Danton, claimed that she was the mind behind the ministry of interior, a job offered to her husband, and that because of this the offer ought not to be renewed in the second revolutionary ministry.

Contemporary historians still talk about her as an intriguante, who used her womanly charms to impose her views on the Girondins. She did in fact share the burden of the ministry with her husband, drafting state letters on his behalf. She did also greatly influence the politics of the Girondins, but they, at least, saw her influence as legitimate, if not legal (she was not a citizen). It is clear from her writings that she cared about the flourishing of the nation at least as much as her political opponents, and a great deal less for power and riches.

less

Bibliography

Primary (selected):

Roland, M.-J. Phlipon 1799–1800. Oeuvres de J. M. Ph. Roland, femme de l’ex-ministre de l’intérieur, vol. III, ed. L.A. Champagneux, Paris: Bidault

Roland, M.-J. Phlipon 1827. Mémoires de Madame Roland, avec une notice sur sa vie, des notes et des éclaircissements historiques, ed. Saint-Aubin Berville and Jean-François Barrière, third edition, Paris: Baudoin Frères.

Roland, M.-J. Phlipon 1864. Mémoires de Madame Roland, vol. II, ed. François Alphonse Faugères, Paris: Hachette.

Roland, M.-J. Phlipon 1900. Lettres de Madame Roland (1780–1793), two vols, ed. Claude Perroud, Paris: Imprimerie Nationale.

Rousseau, J.-J. 1761 (1997). Julie, or the new Heloise, trans. and annotated by Philip Stewart and Jean Vache, Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England.

Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft 1840. Lives of the Most Eminent French Writers, Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard.

Archival resources (selected):

The Roland family papers are collected in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France mss naf 9532, 9533, 9534. These documents are also digitized and available through Gallica.bnf.fr

Web resources (selected):

All the editions of Marie-Jeanne Roland’s Memoirs, correspondence and other works are available either on Gallica.bnf.fr or Google books.

Issues with the sources

Early collections and editions (Champagneux), which were based on the manuscript copy by Bosc, were censored to exclude references to her lover Buzot, and to her childhood sexual assault. This was rectified in later editions (Faugères)

Papers were lost or burnt because she had to smuggle them out of prison and entrust them to people who also did not want to get caught with them. The first draft of the ‘Historical Notice’, the part of her Memoirs that deals with the Revolution, was burnt. Marie-Jeanne had entrusted her manuscripts to friends who visited, such as Champagneux Sophie Grandchamp, and Helen Maria Williams. But when those friends were threatened with arrest, they either had to hide or destroy her papers. Marie-Jeanne rewrote her Historical Notices and she did so in a rush as she knew she had little time left.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully