Birth

N/A (Unclear, Toledo? circa 1482, Spain)

Education

Unknown, VariableDeath

1546-47?, Puebla de los Ángeles, México

Religion

Jewish, UnknownMaría de Estrada was a Spanish woman who took part in the expedition of Hernán Cortés to Mexico. She was a politically and religiously active Jewish woman, and she performed many exploits of valor, including demanding to Hernán Cortés that no women be left behind at Tlaxcala.

Personal Information

Name(s)

María de Estrada (also known as María Estrada, María Destrada, María de Estrade or Miriam Pérez), Encomendera of the city of Tetela del Volcán, Mexico.

Date and place of birth

N/A (Unclear, Toledo? circa 1482, Spain)

Death and place of death

1546-47?, Puebla de los Ángeles, México

Family

Mother: Unclear

Father: Unclear

Marriage and Family Life. [Mention women relatives by name and dates, especially those of consequence. Spouse and children.]

Spouse 1: Pedro Sánchez Farfán, died c. 1536

Spouse 2: Alonso Martín (Partidor)

Education

Little detail of her education is known apart from fictionalized biographies that confirm she was being cared for and educated in her early childhood in the city of Toledo, Castile, as a Jew and was given to a friendly travelling Gypsy family when her parents fled the city and her grandfather was imprisoned for refusing conversion.

Religion

Probably from a Jew family who went to prison and to exile due to the Royal decree by which in 1492 Jews were forced to abandon their faith or leave the country.

Transformation(s)

- 1519: voyage to America, first to Cuba and later to Mexico.

- 30th June 1520: Battle of Tenochitlan, known as “la noche triste” [the sad night]

- 10th July 1520: Battle of Otumba.

- Speech to Cortés in Tlaxcala vindicating the role of women and wishing not to be left behind.

- Her active role vindicating the role of women in the American conquest was significant for the chroniclers. However, she was also influential by ultimately vindicating her role as a crypto-Jew and a forced migrant.

Contemporaneous Network(s)

María was part of a wide-ranging familial Jewish network in Toledo, where they had good relations with travellers, Roman Catholics and moors. Her education as a member of a medical family made her an attractive proposition for both of her husbands and gave her connections which she personally could leverage for personal and political benefit: she even claimed positions to the Spanish King on account of her prominent roles in the American conquest.

In terms of female networks, she was connected to the wives of all the conquerors as well as with their husbands. These networks also assisted María in finding a place in the chronicles of Indies and a place in history, albeit a modest one.

She probably established a crypto-Jew community in Tetela del Volcán, Mexico (Zerón Zapata 20-21).

The concept of feminism is anachronistic for this period but, as noted elsewhere, María was very active politically and religiously throughout her life, and her discourses defending women have been reproduced in different history books in various languages.

less

Significance

Works/Agency

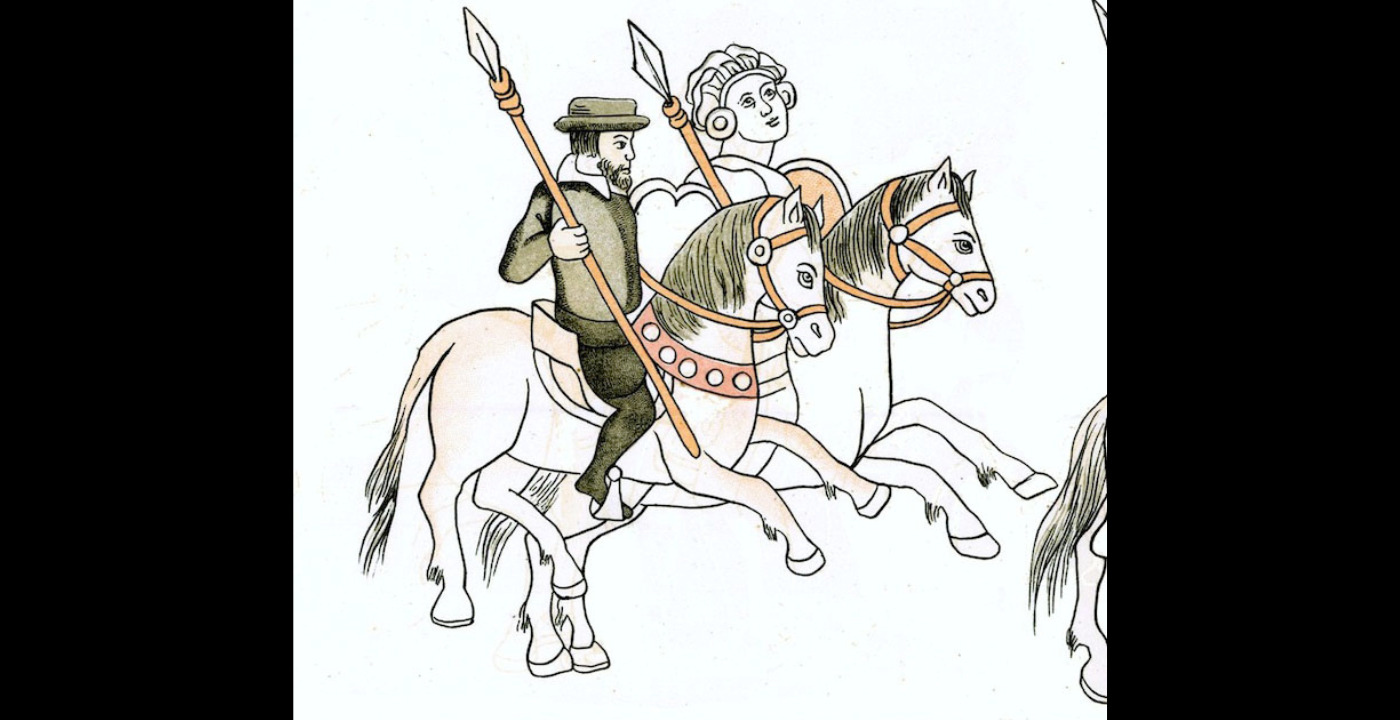

Significant evidence of her political agency and activity throughout her life, examples include her intercession with the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés not to leave women behind in battlefields. She fought by the side of her first husband, Sánchez Farfán, both in Tenochtitlan (June 30th, 1520), where Cortés retired after a serious defeat known in Spanish as “la noche triste” (the sad night), and in the battle of Otumba (July 10th 1520). She performed extraordinary exploits of valour: on the one hand, she charged against the natives on horseback like men, and, on the other, she rejected Hernán Cortés’s plans to leave women behind, at Tlaxcala, displaying powerful speech abilities when defending the appropriateness of women for every task that men could perform (Clayton, E.C., p. 166). Most contemporary chroniclers of the conquest of Mexico stated her honour and valiant deeds (Cervantes de Salazar, F., p. 209, Torquemada J. p. 504, Muñoz Camargo, D, p. 71, Díaz del Castillo, B. p. 400). She is mentioned in a letter from Fray Juan de Zumárraga, Bishop of Mexico, to the King of Spain asking for estates in the town of Tetela in order to found a school, one of which is said to belong to María d’Estrada, widow (Dec. 20th, 1537 Memorial).

Contemporaneous Identifications

Estrada has been researched and written about in terms of Spanish and American history and more recently in connection with women’s studies. She has been examined in relation to her roles as conquistadora, Encomendera and in connection to her marital status. She has rarely been studied as a figure in her own right although there are a few pieces (see bibliography), which deal with her individual role in her lifetime from the points of view of history (Duvenard Chauveau) and fiction (Durán), respectively.

Reputation

María’s reputation, both during her lifetime and in later historiography, has been decidedly mixed, from merely absent to those sources which praise her valour and deeds but mostly ignore ethnic and religious issues. For more on her reputation (see Works/Agency)

Legacy and Influence

Legacy perpetuated in Chronicles of Indies and biographies. By subverting the secondary roles that women were supposed to perform within the corps of the conquistadores, she was able to vindicate agency for all Castilian women, and be instrumental in the salvation of both men and women in the theatre of operations as well as to defend her role as a Jew and a migrant woman.

less

Controversies

Controversy

María de Estrada must have been in the centre of the ethnic and religious controversies of the Exodus from Spain as an unknown member of the expelled Jew community, although covertly. Nothing about her Jew origins is mentioned by chroniclers.

New and unfolding information and/or interpretations

After voluntary or forced migration, Estrada adopted the role of the colonizer by subverting the secondary roles that women were supposed to perform within the corps of the conquistadores. Over time, her possible Jew origin gives a new perspective to her otherwise extraordinary life.

less

Bibliography

Primary (selected)

Booth, Alison et al. eds. Collective Biographies of Women: An Annotated Bibliography. Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 2004. Web 20 Nov. 2016.

Boyd-Bowman, Peter. Índice geográfico de más de 56 mil pobladores de la América Hispánica. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1985.

Campuzano, Luisa. “Blancas y “blancos” en la conquista de Cuba.” Las muchachas de La Habana no tienen temor de Dios… Escritoras cubanas (s. XVIII-XXI). Havana: Ediciones Unión, 2004: 171-199.

Cervantes de Salazar, Francisco, Crónica de la Nueva España II. 1560. Ed. Manuel Magallón. Madrid: Atlas, 1971.

Clayton, Ellen Cleathorne [afterward Needham]. Female Warriors: Memorials of Female Valour and Heroism from the Mythological Ages to the Present Era, London: Tinsley Brothers, 1879.

Croix, Jean François de la. Dictionnaire historique portratif des femmes célèbres. Vol. 2. Paris: Chez L. Cellot, 1769.

Díaz del Castillo, Bernal. Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España. circa 1568-1575. Madrid: Fundación José Antonio de Castro, 2012.

Durán, Gloria. María de Estrada. Gypsy Conquistadora. Pittsburgh: Latin American Literary Review Press, 1999.

Duvenard Chauveau, Juan. María de Estrada. La heroína de la conquista. Cuernavaca, México: 1989.

Feijóo y Montenegro, Fray Benito Jerónimo. “Defensa de las mujeres.” Teatro crítico universal. I. 16. Madrid: Joaquín Ibarra, 1726.

---. An Essay on Woman, Or, Physiological and Historical Defence of the Fair Sex. Translated from the Spanish of El Theatro Crítico. London: W. Bingley, 1765. Pam Morris, ed. Conduct Literature for Women 1720-1770. Vol. 6. London: Pickering & Chatto, 2004: 301-418. 1768, 1774 ed. Web Aug 2012. No translator mentioned in any ed.

---. Théâtre critique. Trans. Nicolas-Gabriel Vaquette d’Hermilly. 2 vols. Paris: Chez Pierre Clément, 1742-45; Paris: Prault père, 1 vol. 1746.

García-Quismondo, Judith. “María de Estrada: de la historia a la ficción.” Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos 781‒782 (2015): 38‒51.

Gómez-Lucena, Eloísa. Españolas del nuevo mundo: ensayos y biografías siglos XVI-XVII. Madrid: Cátedra, 2013.

Hale, Sarah Josepha. Woman’s Record; or Sketches of all Distinguished Women from “the Beginning”till A.D. 1850. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1853.

Hays, Mary. Female Biography; or, Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women of All Ages and Countries: Alphabetically Arranged. (1803) Ed. Gina Luria. 6 Vols. London: Pickering & Chatto. 2013.

Himmerich y Valencia, Robert. The Encomenderos of Nueva España 1521-1555. Austin: University of Texas P, 1996.

Luria, Gina. “General Introduction.” Female Biography, by Mary Hays. Vol. I. London: Pickering & Chatto, 2013: xi-xxx.

María Jesús Lorenzo-Modia, "Mary Hays’s Biography of María de Estrada, a Spanish Woman in the American Conquest" Es Review, 38, 2017: 11-25,

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24197/ersjes.38.2017

Maura, Juan Francisco. Españolas de ultramar en la historia y en la literatura. Valencia: Universidad de Valencia, 2005.

Memorial de los Obispos de Nueva España, Biblioteca Nacional de España, ms.19697, 14.

Muñoz Camargo, Diego. Historia de Tlaxcala. (1576-1591) México: Ed. Alfredo Clavero, 1892. Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes, 2007. Web. 2 August 2012.

Pumar Martínez, Carmen. Españolas en Indias: mujeres-soldado, adelantadas y gobernadoras. Madrid: Anaya, 1988.

Torquemada, Fray Juan de. De los veinte y un libros rituales y monarquía indiana, con el origen y guerras de los indios occidentales, de sus poblazones, descubrimiento, conquista, conversión y otras cosas maravillosas de la mesma tierra. Sevilla: Matías Clavijo, 1615. Madrid: Nicolás Rodríguez, 1723. 2nd printing.

Zerón Zapata, M. ‘Crónica de la Puebla de los Ángeles.’ (ca. 1650). La Puebla de los Ángeles en el siglo XVII. Mexico: Ed. Patria, 1945. 20-21.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully