Birth

1907

Death

1987

Invoked as one of the leading feminist literary voices of modern India from North India, her voluminous contributions brought to light many of the concerns of the time, most significantly the “condition of women.” As one of the pillars of Chhayavaad, the literary renaissance in Hindi writing, Mahadevi was among the foremost women writers who, through her poetry, prose, essays, editorials, and other contributions, articulated the necessity of contesting the binary of the “personal” and the “political,” arguing that this division was artificial and that the “cultural” and the “social” realms must be understood as deeply “political.” Her editorship of Chand, the leading women’s journal of the 1930s–40s, was instrumental in bringing forth writings with deep imprints of nascent feminism. She was also a key participant in the nationalist struggle for independence against British colonialism, with pronounced Gandhian influence.

Personal Information

Name(s)

Mahadevi Verma

Date and Place of Birth

1907, Farrukhabad, Uttar Pradesh, India

Date and Place of Death

1987

Family and Life in Context

In the early twentieth century, the Hindi literary circle emerged in colonial North India, marking a significant moment of change and expansion in the Hindi public sphere. The Hindi language market produced literature, but women’s participation in literary activities remained limited due to patriarchal and socio-cultural restrictions. Nevertheless, modern literary culture developed in North India, and a gradual transformation occurred in which women increasingly engaged in literary writing. This was remarkable, considering that most women lacked access to education; the female literacy rate in Uttar Pradesh in 1911 was just one percent.

Mahadevi Verma was a literary figure who made significant contributions to Hindi literature and redefined the role of women in intellectual and cultural spheres.1 Often hailed as the “fourth pillar” (chaturth stambh) of the Chhayavad era of Hindi literature, alongside Jaishankar Prasad, Suryakant Tripathi ‘Nirala,’ and Sumitranandan Pant,2 Verma’s literary oeuvre reflects her thoughts, conduct, and sensitivity to social consciousness.3

Mahadevi Verma was born in 1907 in Farrukhabad, Uttar Pradesh, India. Her birth coincided with the vibrant festivities of Holi, a prominent festival celebrated across North India, symbolising the arrival of spring and the triumph of good over evil. On September 11, 1987, at the age of eighty, she took her last breath in Prayagraj.4 Her mother’s name was Hemrani Devi, and her father was Govind Prasad Varma, a Sanskrit scholar who adhered to the traditional values of Hindu society. Her father’s extensive library and his love of literature inspired her deep appreciation for poetry and literature. She began writing poetry at a young age, drawing inspiration from the natural beauty of her surroundings and the mythological stories her father shared with her.

At the age of nine in 1916, Mahadevi Verma was married to Dr. Swarup Narain Varma.5 He was a physician by profession, and Verma refused to live with him after graduating. She cited their incompatibility, finding his hunting and meat-eating offensive, which she could not tolerate. She had always been deeply influenced by her father—his love of nature, appreciation of beauty, and sensitivity to the natural world. When her father suggested that she convert to Christianity to obtain a divorce and remarry, she firmly refused to do so.6 The magnitude of courage this act required is difficult to fathom. Equally striking was the restraint and empathy her parents showed in refusing to compel her to conform to social or familial expectations.

Education

Born into an educated family and deeply immersed in literary and intellectual pursuits, Verma was provided with a broad-based and inclusive education. Her instruction was entrusted to a Pandit and a Maulvi for classical and linguistic training, alongside teachers of painting and music, reflecting her family’s progressive vision and dedication to cultivating intellectual and aesthetic sensibilities. Mahadevi’s education began at a young age in 1912 when she attended a Mission School in Indore.7 Verma was initially admitted to a convent school, but due to protests and her unwilling attitude, she was subsequently admitted to Crosthwaite Girls’ College in Allahabad.8 Later she continued her education in 1919 at Crosswait College, Prayagraj, while residing with her parents, and her husband was then pursuing his own studies in Lucknow. In 1921, she passed her matriculation exams with distinction, became the province’s topper, and earned a state scholarship. In 1925, she passed the entrance exams with distinction,9 and she successfully completed her 12th-grade exam.10 By continuing her education Mahadevi completed her B.A degree in 1929, form Allahabad University. However, due to certain health-related issues, she has taken a break from her higher studies. During this period, she predominantly resided in Takula, Nainital. However, her literary journey began early, and she continued to publish numerous collections of poetry, prose, essays, and plays throughout her career.

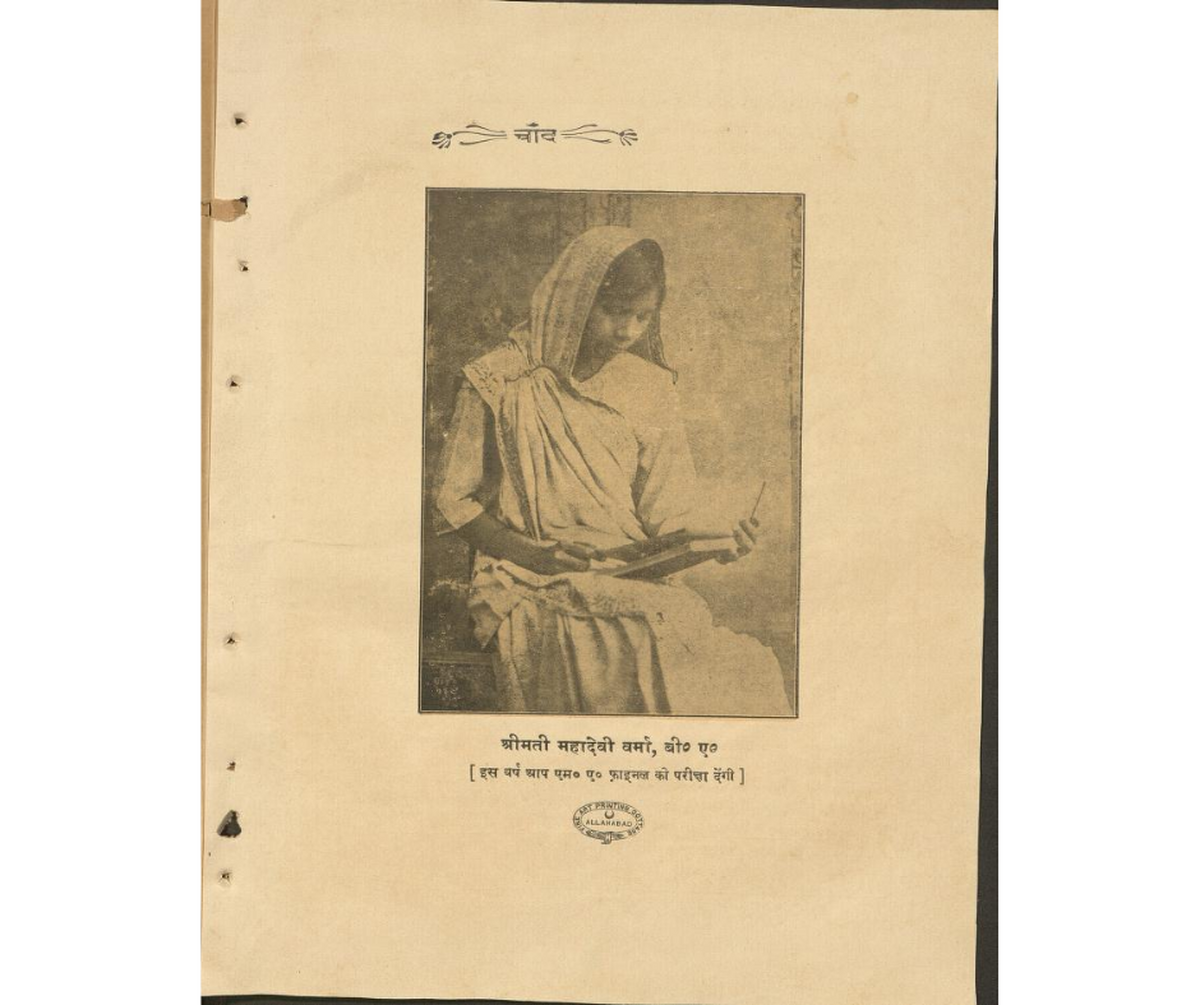

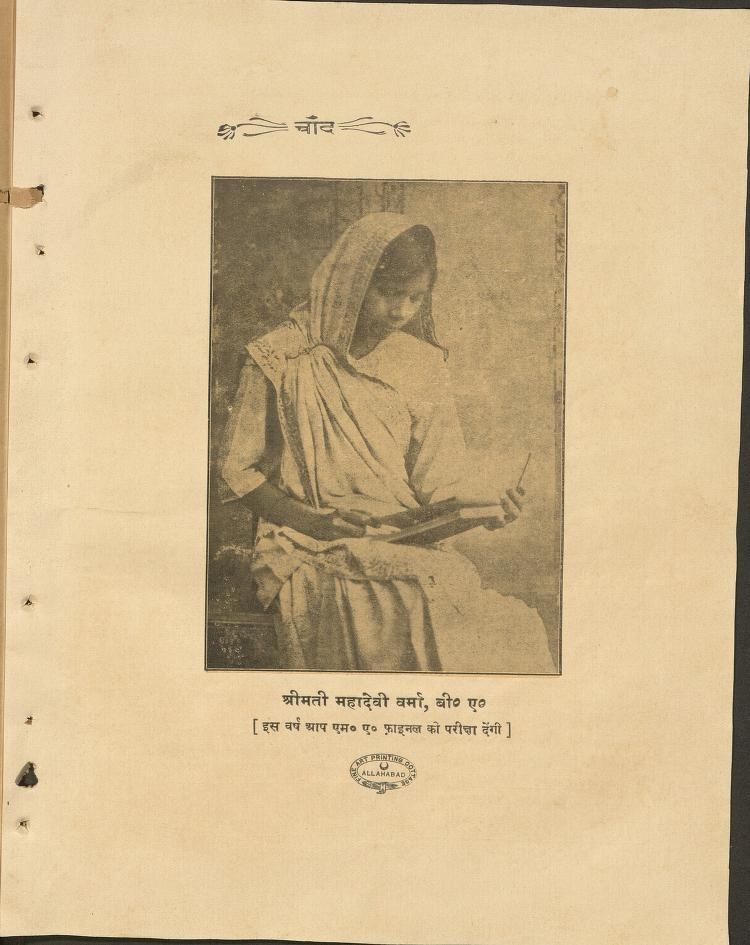

Chand magazine, a leading publication of its time, was committed to promoting women’s education and disseminating information related to schools and colleges. It regularly featured local news aimed at fostering educational awareness, with articles titled “Crosthwaite School and College,”11 which notably highlighted prominent individuals such as Mahadevi Verma.12

From an early age, she wished to become a bhikṣuṇī due to her deep devotion to Lord Buddha. After completing her B.A. in 1929, she met the prospective mentor Bhikṣu Mahāsthavir in Nainital, but his decision to speak from behind a wooden partition struck her as humiliating. Viewing this as a sign of deep mistrust, she abandoned her plan to become a bhikṣuṇī. Subsequently, her contact with Mahatma Gandhi at Takula, Nainital, inspired her to turn toward social service.¹³ From a young age, she developed a deep sense of introspection and compassion, which made her highly sensitive to both animals and the natural environment.14 Her profound respect for all forms of human life inspired her to dedicate much of her time to tending to injured birds, reptiles, and other animals.15 Mahadevi attributes her inclination towards sorrow to both her previously privileged and fortunate life, as well as her deep admiration for Buddhist philosophy, which views the world through the lens of suffering.16

In 1932, she completed her M.A. in Sanskrit from Prayag University,17 further solidifying her intellectual and academic foundation.18 In the same year, she assumed responsibility for ‘Prayag Mahila Vidyapeeth’ and volunteered as the editor of the Chand journal without compensation.19

Belief Systems

Influenced by Buddhist philosophy and inspired by Mahatma Gandhi during her time in Takuli, Nainital, she developed a strong inclination towards social work. Her daily activities involved visiting villages around Prayagraj, teaching children, and actively participating in their educational development, a commitment she upheld until India gained independence.20 In 1937, she constructed a Meera Mandir in Ramgarh, Nainital. She has often been revered as the ‘Meera’ of the twentieth century for her profound spiritual sensibility and lyrical expression within the Hindi Chhayavad tradition. By infusing emotional depth and intellectual rigour into Khari Boli prose and poetry, she helped shape modern Hindi as a language capable of expressing both personal introspection and social critique.

As a prominent advocate of women’s education and emancipation, Verma emphasised the necessity of a holistic and humanistic educational system that would nurture both the intellectual and moral development of women. In her essays, such as “Nari aur Shiksha” and “Shiksha aur Mahila,”21 she argued that education should not merely prepare women for domesticity but should enable them to contribute meaningfully to the nation’s cultural and social progress.22 Profoundly connected to her personal experiences and the socio-political realities of her time, her writings—spanning from the early to the late twentieth century—combine poetic introspection with a feminist reformist vision.23 Her poetry collections, such as Yama (1940),²¹ and her prose essays, including Srinkhala ki Kadiyan (1942)25 and Sandhya Geet,26 articulate the emotional and intellectual struggles of women in a patriarchal society. Through these accomplishments, she emerges not merely as a poet of romantic idealism but also as a social reformer deeply committed to women’s emancipation and education during and after the Indian independence movement.27

Her writings also offered a sharp critique of regressive social institutions such as the dowry system, which she denounced as a practice that fragmented familial solidarity and commodified women. Verma viewed dowry as a socio-economic evil that reduced daughters to financial liabilities and weakened the ethical fabric of the community by transforming marriage into a transactional relationship.28 For Verma, education was not merely an instrument of literacy but a transformative force that enabled women to attain dignity, self-reliance, and a meaningful role in modern Indian society.29

less

Significance

Academic Contributions

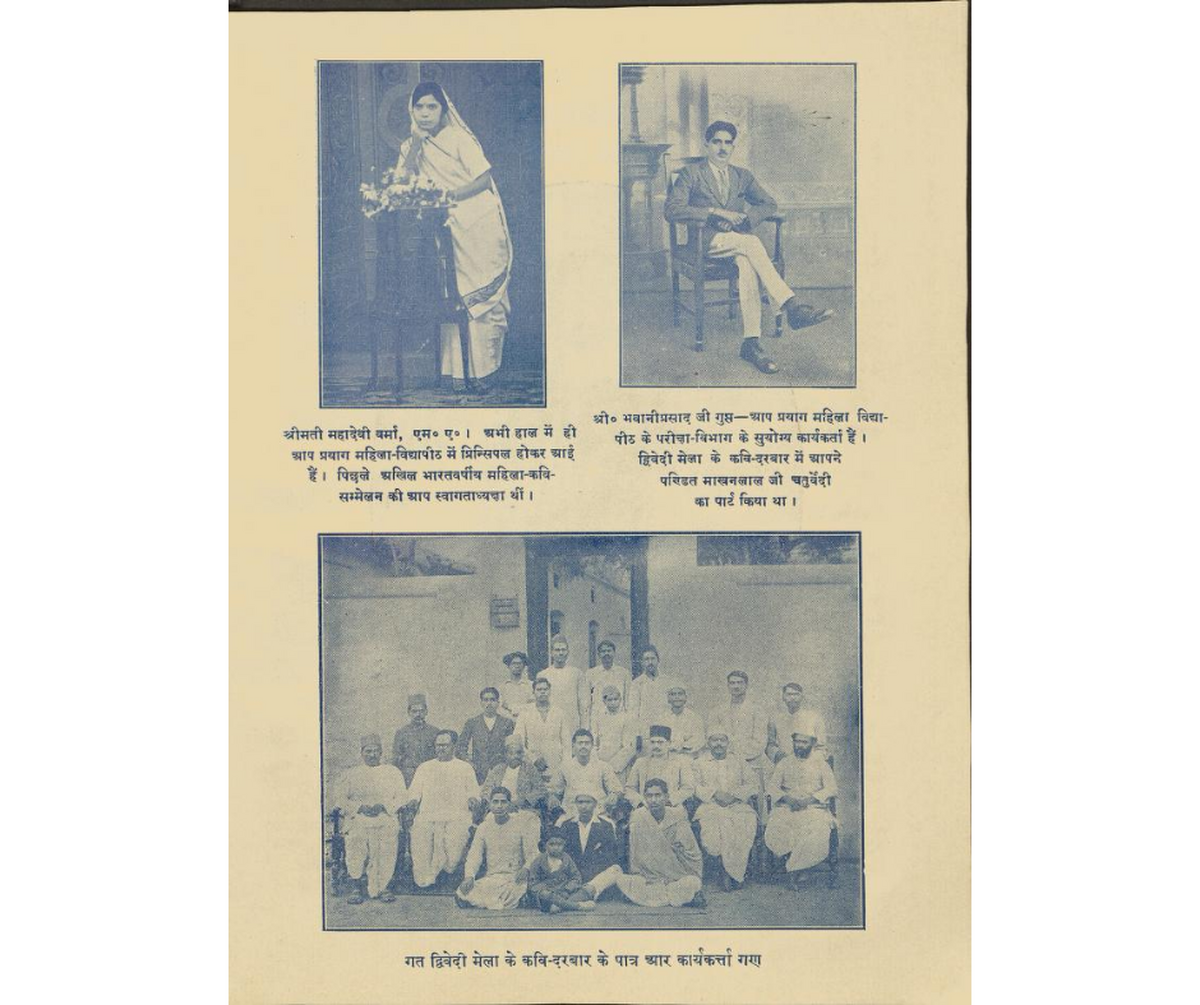

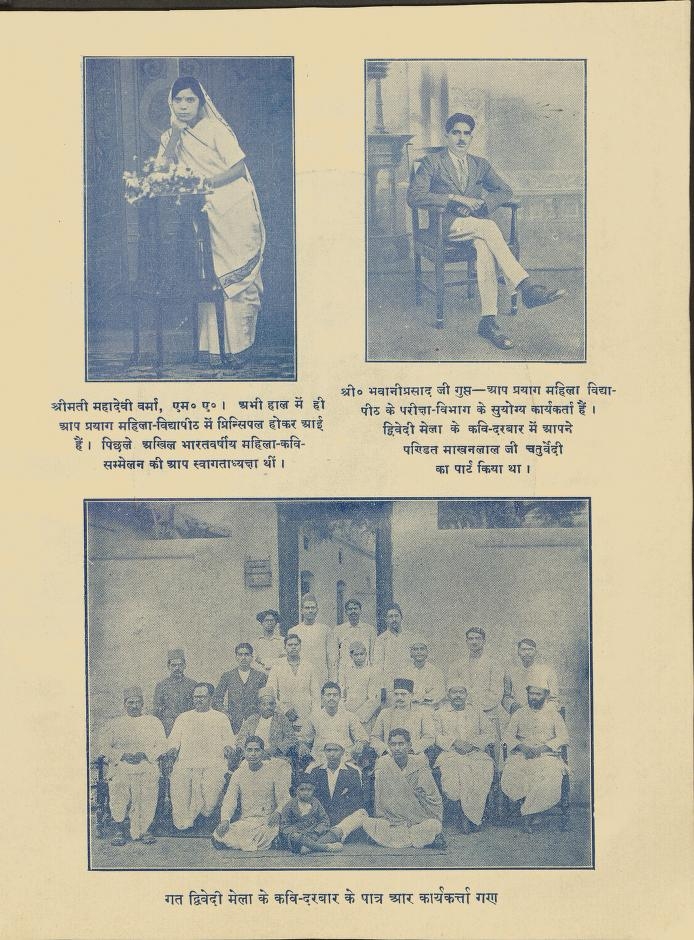

In 1933, Mahadevi Verma organised the All-India Women Poets’ Conference in Prayag (Allahabad), a landmark event in the history of women’s literary and intellectual movements in India. During this period, she also served as the Principal of Prayag Mahila Vidyapeeth, an institution dedicated to women’s education, as reported by Chand magazine.30 The magazine published an accompanying photograph portraying Mahadevi Verma standing beside a flower vase, dressed in traditional Indian attire—an image that symbolically reflected the intersection of tradition and modernity in early twentieth-century women’s cultural expression. After that, she served as an editor of Chand, from 1935 to 1938, both positions without remuneration, reflecting her dedication to education and literature.31

In 1933, again a Mahila Kavi Sammelan was organised by the Mahila Sahityik Sabha of Prayag Mahila Vidyapeeth, where she hosted the event32 and met Rabindranath Tagore (referred to as Kavindra Ravindra), initiating Meera Jayanti, a celebration dedicated to the poet-saint Meera Bai. Her literary work substantially influenced the modernization and standardization of the Hindi vernacular, particularly through her composition exercise of Khari Boli, which evolved from the earlier Braj Bhasha poetic tradition.33

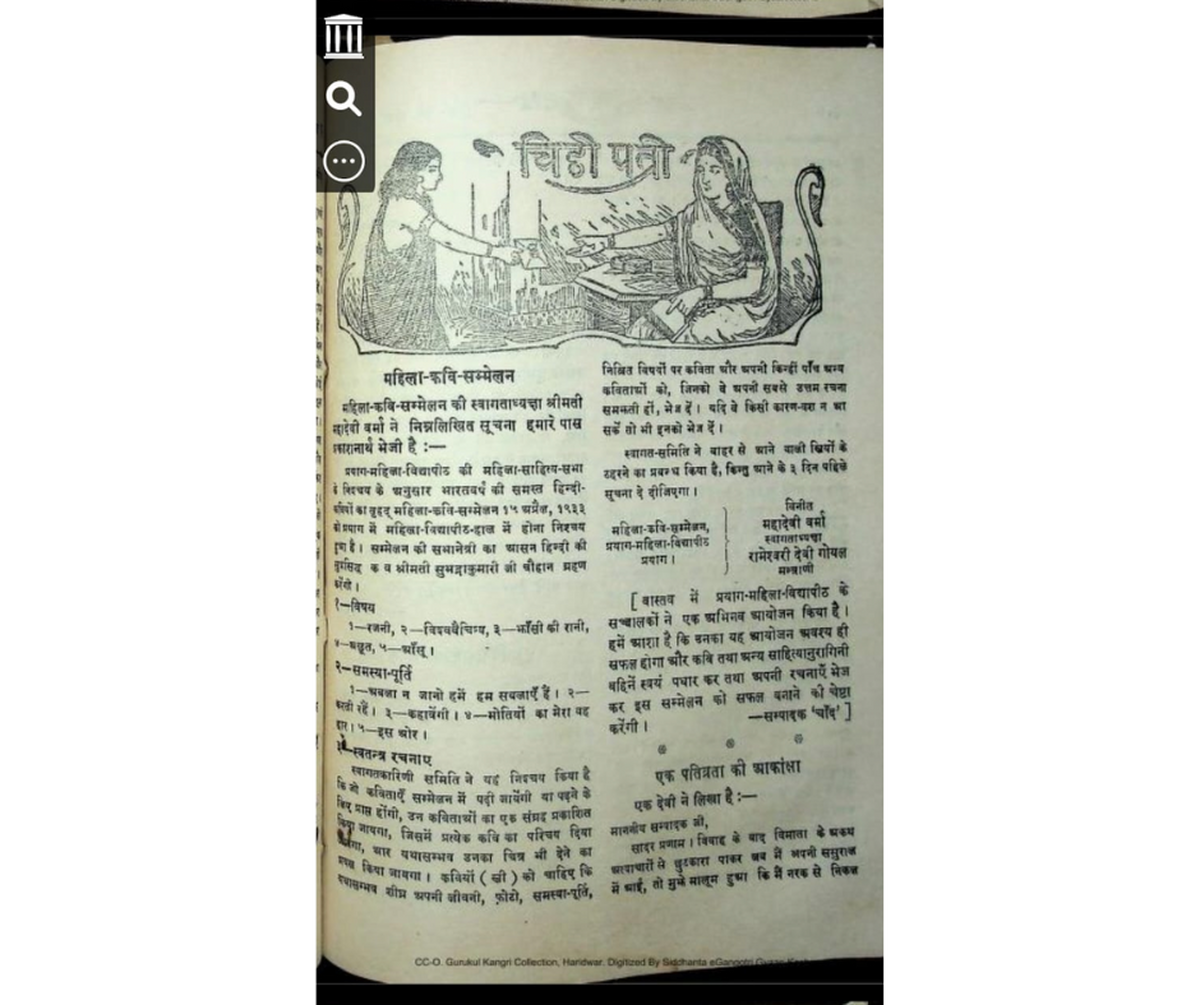

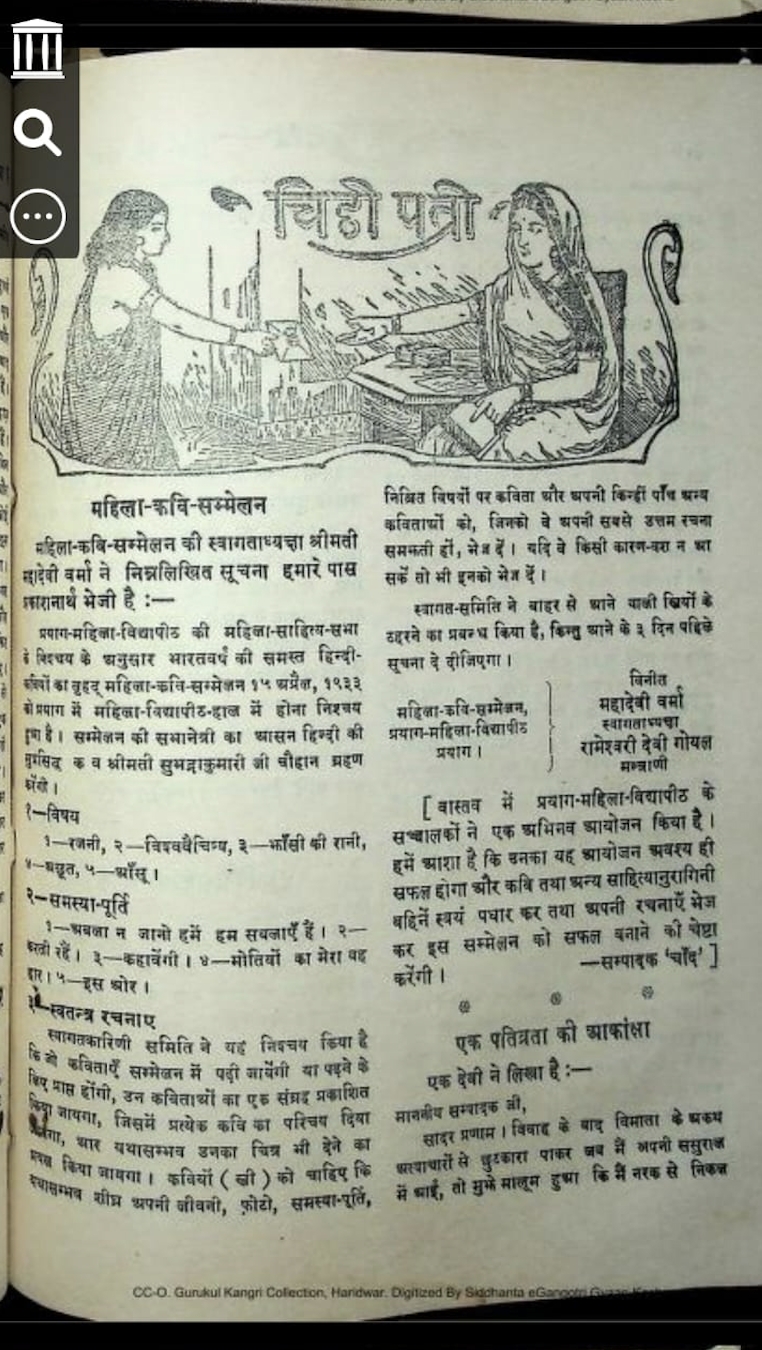

Chand. 1933. Chitthi Patri column: ‘Mahila Kavi Sammelan’34

This document is a significant historical record from Chand magazine, showing Mahadevi Verma’s visionary role in institutionalising women’s literary voices in colonial North India. This Women Poets’ Conference was conceived and executed under her leadership at Prayag Mahila Vidyapeeth. The report in Chand emphasises the active participation of women poets and the intellectual ambition behind this gathering. The event symbolised a major step in women’s literary awakening, particularly in the Hindi literary public sphere, which was dominated by male intellectuals. Mahadevi Verma’s initiative to organise such a conference was an act of cultural assertion, establishing a separate and respected platform for women writers, poets, and thinkers to share their creative works and discuss gendered experiences of art and society.

The Mahila Sahitya Sabha (Women’s Literary Association) of Prayag Mahila Vidyapeeth resolved to organise the All-India Women Poets’ Conference at Prayag on April 15, 1933, to be held in the auditorium/hall of the Vidyapeeth. The presidential speech was delivered by Subhadra Kumari Chauhan. Her poems included subjects such as “Jahansi ki Rani,” “Rajni (Night),” “Vishwavaichiva,” and “Achhoot.” The section ‘Problem Completion’ (samasya poorti) invited poets to respond to poetic prompts, such as (abla na janon ham sablayen hain) ‘don’t think we are weak; we are toughened women.’35

As the editor of Chand, she used the journal as both a platform and an archive of women’s literary history. Through this report, she not only documented the event but also legitimized women’s participation in emerging literary culture. The mention of women poets presenting compositions and the careful curation of themes related to ethics, aesthetics, and emotional consciousness indicate Mahadevi’s effort to bridge the domains of literature and reform. It represented the collective assertion of women’s authorship in Hindi literary sphere.

Chand, May 1933, Image of the poet participated in Akhil Bhartiya Mahial Kavi Sammelan

In 1942, she was the editor of the Buddha Ank of the journal Vishvawani, furthering her engagement with Buddhist themes, a lifelong interest. A year later, in 1943, she received the prestigious Dwivedi Puruskaar for her poetry collection Smriti ki Rekhayen. In 1944, Mahadevi Verma was honoured with the ‘Mangala Prasad Parishad Purushkar,’ and that same year, she founded the Sahityakar Parliament, a significant platform for literary discussions and promotion of Hindi literature.37 In the same year, Mahadevi Verma released her critical work Adhunik Kavi, providing an insightful examination of modern Hindi poetry and the innovative spirit of her contemporaries. This volume delves into the philosophical and emotional dimensions of poetic expression amid a swiftly evolving cultural landscape. Enhanced by illustrations from Sambhunath Mishra, the book visually enriches Verma's profound literary analysis.38

In 1950, she organised the All India Writers’ Conference and Sahitya Parv on behalf of the Sahityakar Sansad,39 where President Rajendra Prasad laid the foundation stone of Vani Mandir. In 1952, she wrote a poem titled Atit ke Chalchitra.40 The event, celebrated from February 18 to 22, featured a literary festival that included a range of cultural and literary programs.41 On February 2, 1956, a newspaper report from Allahabad announced the achievements of Padma Bhushan Shrimati Mahadevi Verma, M.L.C. (elected in 1952), a distinguished poet, eminent Hindi litterateur, and Principal of the Prayag Mahila Vidyapith, who was felicitated by leading Hindi scholars, publishers, journalists, and members of the public. The gathering celebrated her being conferred the prestigious ‘Padma Bhushan’ by the President of India, Dr. Rajendra Prasad, in recognition of her outstanding contributions to modern Hindi literature, women’s education, and the institutionalisation of literary culture in North India.42

She undertook a literary tour of South India with renowned writers such as Shri Ilachand Joshi, Dinkar, and Gangaprasad Pandey, and advocated for amendments to the copyright rules from the Central Government. She played a key role in securing Nirala’s copyrights through Sahityakar Sansad and published a collection of his poems titled Apara.43 On January 30, 1963, the foundation stone for the Nirala Memorial was laid with great ceremony at the Daraganj crossing in Allahabad by the renowned poet Mahadevi Verma. This marked a significant community effort to recognise and safeguard the literary and cultural legacy of Suryakant Tripathi ‘Nirala.’ Reports from that time highlight Verma’s speech, in which she emphasised Nirala’s strong opposition to injustice and his lifelong commitment to addressing human suffering through compassion. The memorial’s proposal and its approval by the Allahabad Corporation serve as an official recognition of Nirala’s pivotal contribution to modern Hindi literature.44 A letter dated December 31, 1963, issued from 160, Bahadurganj, Allahabad by Dev Dutt Shastri, invites scholars to contribute essays for the Mahadevi Abhinandan Granth. In this letter, the brief communication highlights the organized literary collaboration of the period and reflects the intellectual prestige Mahadevi Verma commanded within Hindi literary circles. The letter serves as an archival testament to the cultural recognition she received and to the efforts of editors such as Dev Dutt Shastri and P. K. Malaviya in documenting her legacy on Madan Mohan Malviya.45 In Prayag, she founded a theatre and arts center called Rangvani, which was inaugurated by Marathi playwright Mama Barekar. During this time, she also stood with national poet Maithilisharan Gupta in protesting a statement made by the then Central Education Minister Maulana Azad regarding Hindi literature, publishing a sharp rebuttal in various newspapers. During the 1970s, Mahadevi Verma continued to receive accolades, including the Vishisht Sahitya Puraskar (1976) from the Government of Uttar Pradesh, a testament to her enduring influence.46 Two years later, in 1982, she was awarded the first Bharat-Bharti Award, worth one lakh rupees, by the Uttar Pradesh Hindi Institute, Lucknow. In 1983, she was honoured with the prestigious Gyanpeeth Award for her works Yama and Deepshikha, receiving one and a half lakh rupees, further solidifying her status as one of the most influential literary figures of modern Hindi literature.

In fact, after a negative experience at a Kavi Sammelan in Lucknow, Mahadevi decided never to recite her poems in public again, a promise she kept. Despite this, Mahadevi remained a prominent figure in literary circles. She regularly participated in seminars and poetry recitals, and occasionally hosted these events. Known as the ‘modern Meera,’ her contributions to Hindi literature were immense and enduring. The work she focused on became integral to modern Hindi syllabi, influencing young minds and shaping their emotions towards society and nature. Mahadevi's legacy in Hindi literature remains profound and timeless.

less

Bibliography

Footnotes

1. Karuna Chanana, “Women in Indian Academe: Diversity, Difference and Inequality in a Contested Domain,” Journal of Indian Education 34, no. 1 (2008): 5–18.

2. Vasudha Dalmia, The Nationalization of Hindu Traditions: Bharatendu Harishchandra and Nineteenth-Century Banaras (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1997).

3. Susie Tharu and K. Lalita, eds., Women Writing in India: 600 B.C. to the Present, vol. 1 (New York: The Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 1993).

4. Roger T. Ames, Wimal Dissanayake, and Thomas P. Kasulis, eds., Self as Person in Asian Theory and Practice (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994).

5. Mahadevi’s marriage remained largely nominal, as both were deeply engrossed in their respective intellectual and professional pursuits. Verma subsequently relocated to Allahabad, where she devoted herself to literary and educational activities, further cultivating her poetic sensibilities and engagement with Hindi literature. Although she and her husband maintained cordial relations, they lived separately for most of their lives, meeting only occasionally. Following her husband’s death in 1966, Verma chose to settle permanently in Allahabad, where she continued her literary, educational, and reformist endeavors until the end of her life. Anita Anantharam, One Day the Girl Will Return: Feminism, Nation, and Poetry in South Asia (Berkeley: University of California, 2003).

6. Karine Schomer, Mahadevi Varma and the Chhayavad Age of Modern Hindi Poetry (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983).

7. Ramji Pandey, ed., Mahadevi: Pratinidhi Gadhya Rachnayen (New Delhi: Bhartiya Gyan Peeth, 2008), 12.

8. Chand, “Vividh Vishaya (Miscellaneous Subjects), Crosswait School or College,” June 1925, 117.

9. In the Samachar (News) column Chand published the name of the girls who qualified 10th and 12th exam. Chand, “Samachar (News) Column,” June 1925, 117. Archive, Hindi Sahitya Sammelan, Allahabad.

10. op.cite.p.2

11. A girls’s institution where many young women of Prayagraj pursued higher education.

12. There were eight students participate in annual M.A. exam, and Mahadevi was sat for this exam. Chand express its gratitude towards her because she was the prominent writer of this magazine.

13. Ganga Prasad Pandey, Mahayashi Mahadevi, Lokbharti Prkashan, Allahabad, p.347.

14. ‘Main to bachpan se hi bhikṣuṇī honā chāhtī thī; par merī mātājī ko yah svīkār nahī̃ thā. Ve bolī̃ ki yah ṭhīk nahī̃ hai. Maine unkī āśā kā pālan kiyā; par phir bhī main aparigrahī hī rahī.’tr.

‘I had wished to become a nun from childhood itself; however, my mother did not approve of it. She said that it was not appropriate. I followed her wishes; nevertheless, I remained non-possessive’. For details, see Shivchandra Nagar, Mahadevi: Vichar aur Vyaktitva (in Hindi), Allahabad: Kitab Mahal, 1953, p. 21.

15. Neera Kuckreja.‘Sohoni, Mahadevi Varma: Simone De Beauvoir's Contemporary and a Leading Poet and Writer from India.’ Simone de Beauvoir Studies 11 (1994): 120.

16. Ibid, 120.

17. David Rubin, The Return of Sarasvati: Four Hindi Poets (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998).

18. Chand, May, 1933.

19. Ganga Prasad Pandey, Mahayashi Mahadevi, Lokbharti Prakashan, Allahabad, p.348.

20. Tracy Pintchman, ed., Seeking Mahādevī: Constructing the Identities of the Hindu Great Goddess (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2001).

21. Mahadevi Verma, Nari aur Shiksha, in Shrinkhala Ki Kadiyan (Allahabad: Kitab Mahal, 1942).

22. Tharu and Lalita, eds., Women Writing in India, vol.1.

23. Saritanjali Bohidar, “Evolution of Consciousness and Identity: A Study of Women Edited Magazines in Orissa (1892–1920),” in Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 71 (2010): 814–821.

24. Mahadevi Verma, Yama, Hindi Books Central Secretariat Library Series (New Delhi: National Archives of India, 1951), Microfilm Repository, Identifier MF_222400085154, File No. Yama, Accession No. 159.

25. Mahadevi Verma, Shrinkhala Ki Kadiyan, Hindi Books Central Secretariat Library Series (New Delhi: National Archives of India, 1951), Microfilm Repository, Identifier MF_222400084150, File No. Srnkhala_Ki_Kadiya, Accession No. 12.

26. Mahadevi Verma, Sandhya Geet, Hindi Books Central Secretariat Library Series (New Delhi: National Archives of India), Microfilm Repository, Identifier MF_222400084163, File No. Sandhya_Geet, Accession No. 14.

27. Geraldine Forbes, Women in Modern India (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

28. Madhu Kishwar, “Gandhi on Women,” Economic and Political Weekly 21, no. 40 (October 4, 1986): 1691–1702.

29. Bohidar, Saritanjali. ‘Evolution of Consciousness and Identity: A Study of Women Edited Magazines in Orissa (1892-1920).’ In Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 71, pp. 814-821. Indian History Congress, 2010.

30. Chand, 1933, retrieved from the Hindi Sahitya Sammelan Prayag.

31. Lalit Joshi, “Cinema and Hindi Periodicals in Colonial India: 1920–1947,” in Narratives of Indian Cinema (2009): 19–52.

32. Chand, “Chitthi Patri,” March 1933, 722.

33. Karine Schomer, Mahadevi Varma and the Chhayavad Age of Modern Hindi Poetry: A Literary and Intellectual Biography (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1976).

34. Chand. 1933. Chitthi Patri column: ‘Mahila Kavi Sammelan.’

36. Mahadevi Verma had been invited by the editor, Shri Vishwambhar Nath, to attend the release of the special issue of ‘Buddha Sanskriti’, a volume that acknowledged her long-standing contributions to Hindi literature and cultural thought. Although she had initially planned to be present at the event, unforeseen circumstances prevented her from attending the ceremony. In her communication to the editor, she expressed her regret for her absence and requested that a copy of the special issue be sent to her. This gesture reflects both her sustained engagement with contemporary intellectual publications and her commitment to encouraging scholarly initiatives in the field of Indian cultural and literary studies. Mahadevi Verma, Letter to B. N. e Requesting a Copy of Buddha’s Letter, Political Branch, Foreign Department, File No. 42, Identifier NAIDLF01032479, Location R1, National Archives of India.

37. Schomer, Mahadevi Varma and the Chhayavad Age of Modern Hindi Poetry, 1976.

38. Mahadevi Verma, Adhunik Kavi, Hindi Books Central Secretariat Library Series (New Delhi: National Archives of India, 1944), Microfilm Repository, Identifier MF_222400084869, File No. ADHUNIK_KAVI_1, Accession No. 112.

39. M. Maheshwari, “In the Interim: Administering Art in India, After Independence, Before Institutions,” India Review 22, no. 1 (2023): pp.43–77.

40. Mahadevi Verma, Atit ke Chalittra (New Delhi: National Archives of India, 1954), Hindi Books Central Secretariat Library Series, Identifier MF_222400086585, Accession No. 379.

41. Anantharam, A. (2003). One day the girl will return: Feminism, nation, and poetry in South Asia. University of California, Berkeley.

42. Congratulations by Hindi Scholars, Poets, and Writers to Smt. Mahadevi Verma on Award of Padma Bhushan, File No. 37, Identifier PP_000002597890, National Archives of India, 3 February 1956.

43. Maheshwari, “In the Interim,”(use exact page range as cited).

44. Foundation Stone of Nirala Memorial Laid, newspaper clipping documenting the foundation-stone laying ceremony by Mahadevi Verma, 30 January 1963, Allahabad; digitized document, National Archives of India, New Delhi.

45. Mahadevi Verma, Requests to Write an Article on “Mahadevi Verma”: Encloses the Title List of Mahadevi Abhinandan for the Selection of Subject, 31 December 1963, File No. 182, Identifier PP_000002598035, Correspondence of Dev Dutt Shastri and P. K. Malaviya, National Archives of India.

46. Ganga Prasad Pandey, Mahayashi Mahadevi, Lokbharti Prakashan, Allahabad, pp.348-352.

Bibliography

Ames, Roger T., Wimal Dissanayake, and Thomas P. Kasulis, eds. Self as Person in Asian Theory and Practice. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994.

Anantharam, Anita. Mahadevi Varma. Amherst, NY: Cambria Press, 2008.

———. One Day the Girl Will Return: Feminism, Nation, and Poetry in South Asia. Berkeley: University of California, 2003.

Bohidar, Saritanjali. “Evolution of Consciousness and Identity: A Study of Women Edited Magazines in Orissa (1892–1920).” In Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 71, 814–821. Indian History Congress, 2010.

Chanana, Karuna. “Women in Indian Academe: Diversity, Difference and Inequality in a Contested Domain.” Journal of Indian Education 34, no. 1 (2008): 5–18.

Dalmia, Vasudha. The Nationalization of Hindu Traditions: Bharatendu Harishchandra and Nineteenth-Century Banaras. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1997.

“Information Retrieved from Chand, Vividh Vishaya (Miscellaneous Subjects), Crosswait School or College, June 1925: 117. Archive, Hindi Sahitya Sammelan, Allahabad.”

Joshi, Lalit. “Cinema and Hindi Periodicals in Colonial India: 1920–1947.” In Narratives of Indian Cinema, 19–52. 2009.

Mahadevi Verma. Atit ke Chalittra. New Delhi: National Archives of India, 1954. (Hindi Books Central Secretariat Library Series, Identifier MF_222400086585, Accession No. 379).

Maheshwari, M. “In the Interim: Administering Art in India, After Independence, Before Institutions.” India Review 22, no. 1 (2023): 43–77.

Pandey, Ramji, ed. Mahadevi: Pratinidhi Gadhya Rachnayein. New Delhi: Bhartiya Gyanpeeth, 2008.

Pintchman, Tracy, ed. Seeking Mahādevī: Constructing the Identities of the Hindu Great Goddess. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2001.

Rubin, David. The Return of Sarasvati: Four Hindi Poets. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Schomer, Karine. Mahadevi Varma and the Chhayavad Age of Modern Hindi Poetry: A Literary and Intellectual Biography. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1976.

———. Mahadevi Varma and the Chhayavad Age of Modern Hindi Poetry. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983.

Sohoni, Neera Kuckreja. “Mahadevi Varma: Simone de Beauvoir’s Contemporary and a Leading Poet and Writer from India.” Simone de Beauvoir Studies 11 (1994): 120.

Source: Chand (1933). Hindi Sahitya Sammelan, Prayag.

Tharu, Susie, and K. Lalita, eds. Women Writing in India: 600 B.C. to the Present. Vol. 1. New York: Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 1993.

Archival Resources:

Archive, Hindi Sahitya Sammelan, Allahabad.

Information retrieved from Chand, “Vividh Vishaya” (Miscellaneous Subjects), Crosswait School or College, June 1925, p. 117.

In the Samachar (News) column, Chand published the names of the girls who qualified for the 10th and 12th examinations. Information retrieved from Chand, June 1925, p. 117.

The news was published in Chand column titled “Chitthi Patri,” March 1933 issue, p. 722.

National Archives of India.

Adhunik Kavi. By Mahadevi Verma. Hindi Books Central Secretariat Library Series. New Delhi: National Archives of India, 1944. Microfilm Repository, Identifier MF_222400084869, File No. ADHUNIK_KAVI_1, Accession No. 112.

Atit ke Chalittra. By M. Verma. New Delhi: National Archives of India, 1954. (Hindi Books Central Secretariat Library Series, Identifier MF_222400086585, Accession No. 379).

Congratulations by Hindi Scholars, Poets, and Writers to Smt. Mahadevi Verma on Award of Padma Bhushan. File No. 37, Identifier PP_000002597890. National Archives of India, 3 February 1956.

Letter to B. N. Pande Requesting a Copy of Buddha’s Letter. Political Branch, Foreign Department. File No. 42, Identifier NAIDLF01032479, Location R1. National Archives of India.

Requests to Write an Article on “Mahadevi Verma”: Encloses the Title List of Mahadevi Abhinandan for the Selection of Subject. 31 December 1963. File No. 182, Identifier PP_000002598035. Correspondence of Dev Dutt Shastri and P. K. Malaviya. National Archives of India.

Sandhya Geet. By Mahadevi Verma. Hindi Books Central Secretariat Library Series. New Delhi: National Archives of India. Microfilm Repository, Identifier MF_222400084163, File No. SANDHYA_GEET, Accession No. 14.

Shrinkhala Ki Kadiyan. By Mahadevi Verma. Hindi Books Central Secretariat Library Series. New Delhi: National Archives of India, 1951. Microfilm Repository, Identifier MF_222400084150, File No. SRNKHALA_KI_KADIYA, Accession No. 12.

Yama. By Mahadevi Verma. Hindi Books Central Secretariat Library Series. New Delhi: National Archives of India, 1951. Microfilm Repository, Identifier MF_222400085154, File No. Yama, Accession No. 159.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully