Birth

1571 or 1579

Death

1653

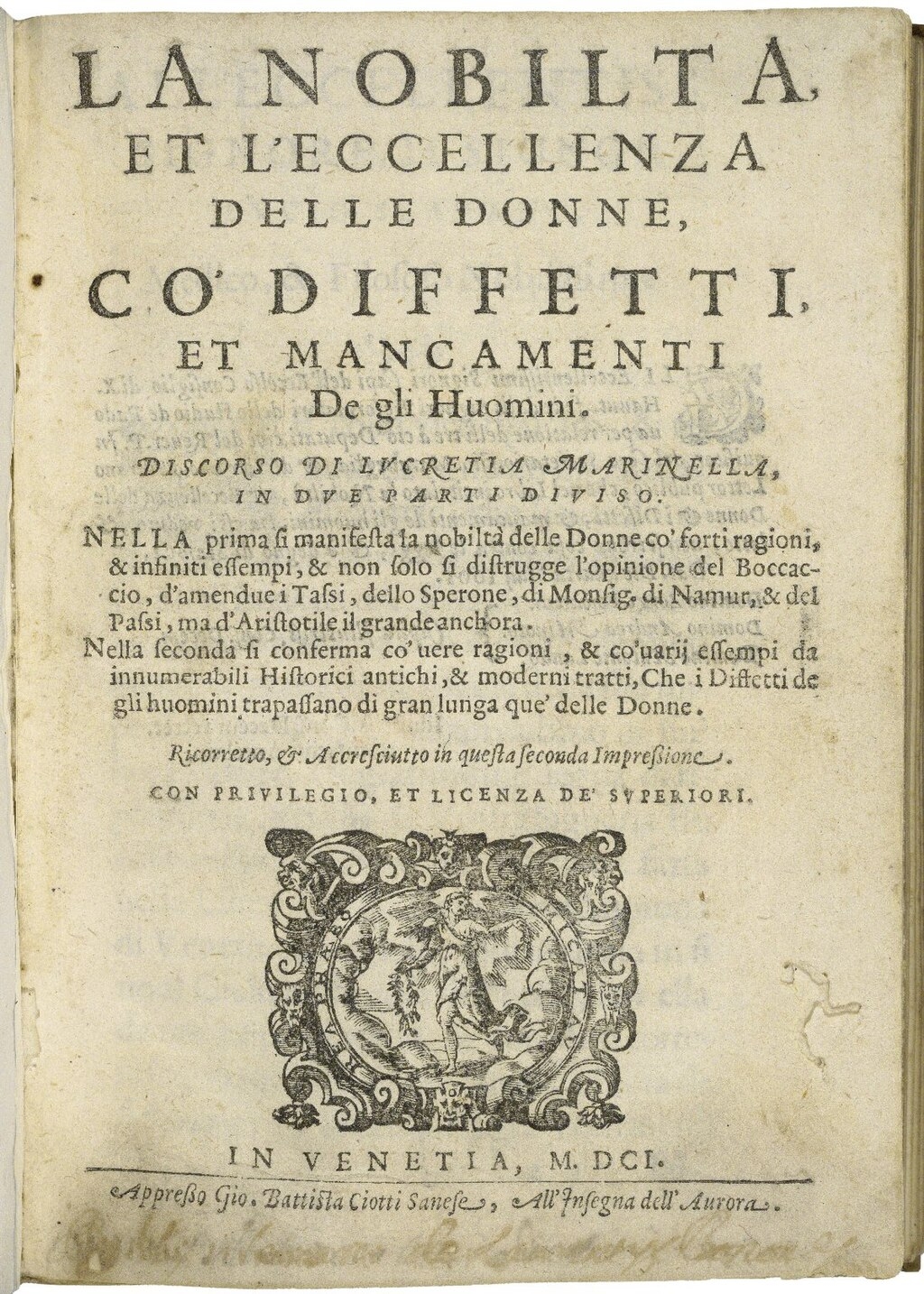

Lucrezia Marinella ranks among the most prolific and versatile authors in early modern Italy, distinguished by her command of a wide range of literary genres and her engagement with subjects traditionally barred to women. She is best known for her treatise La nobiltà et l’eccellenza delle donne, co’ difetti et mancamenti de gli huomini (The Nobility and Excellence of Women and the Defects and Vices of Men, 1600; 1601; 1621), a landmark in the history of feminism.

Personal Information

Name(s)

Lucrezia Marinella

Date and place of birth

Venice, 1571 or 1579

Death and place of death

Venice, 1653

Family

Mother:

Unknown

Father: Giovanni Marinelli (dates unknown), physician and natural philosopher. Author of several works, including two volumes addressed to women, Gli ornamenti delle donne (The Ornaments of Women, 1562) and Le medicine partenenti alle infirmità delle donne (Medicines for Women’s Infirmities, 1563).

Marriage and Family Life

The Marinelli family was wealthy, belonging to the citizen class (immediately below the patricians). Lucrezia had at least three siblings: a sister, Diamantina, and two brothers–Curzio (d. 1624), a physician, and Angelico, a priest. On August 31, 1607, Marinella married Girolamo Vacca (d.1629), a physician. The couple had two children, Antonio (d. 1662) and Paolina.

Education

Although there is little documentary evidence regarding Marinella’s education, we can assume that she received a humanist education on par with that of an elite male peer. Given Giovanni Marinelli’s seemingly progressive views on women, reflected in the attention he gives to the female condition in his works, it is likely that he encouraged his daughter’s academic interests. Her brother Curzio, a physician and author of medical and philosophical texts, oversaw her upbringing until her marriage and may have played an even more important role in fostering her intellectual development. Marinella would have had privileged access to the family’s library, which undoubtedly supported the breadth of her learning. Contemporary humanist Francesco Sansovino praised her dedication to study, and Cristofano Bronzini later celebrated her abilities in philosophy, poetry, and music, particularly her skill on the lute. Marinella’s education was exceptionally advanced in the fields of theology and philosophy. Her erudition is on full display in The Nobility and Excellence of Women, where she draws authoritatively on the classical canon, including Epictetus, Cicero, Plutarch, Ovid, Porphyry, Livy, Diogenes Laertius, Seneca, and most frequently turning to Plato and Aristotle. She also cites a number of medieval theologians, from Saint Bernard of Clairvaux to Peter Lombard, alongside early modern thinkers like Marsilio Ficino and Leone Ebreo (Yehudah Abravanel). The preface to La vita di Maria Vergine Imperatrice dell’universo (The Life of the Virgin Mary, Empress of the Universe, 1602), providing a sort of literary-devotional statement, is also a testament to Marinella’s eclectic range of sources, including Aristotle and Torquato Tasso, but also Marsilio Ficino and Bartolomeo Fonte, as well as Sidonius Apollinaris and Saint Augustine.

Marinella’s philosophical and theological knowledge did not go unnoticed: her allegorical exegesis of Luigi Tansillo’s Lagrime di San Pietro (Tears of Saint Peter, 1606) is prefaced by a striking publisher’s opening note, which lauds her for improving the prestigious male-authored text with a learned commentary steeped in philosophy and theology. Furthermore, the editor of her hagiography on Catherine of Siena (1624) described the work as ‘abounding in theological wisdom,’ while the preface to her hagiography on Francis and Clare of Assisi (1643) hailed it as a ‘theological and philosophical book’–rare accolades for a female author in early modern Europe.

Religion

Catholic. Marinella’s religious writings not only outnumber her secular works but also enjoyed greater popularity among her contemporaries. She adopted an evangelising role from her earliest devotional publications to her last work. Powerful holy women rule over the textual universe of Lucrezia Marinella, who penned a life of the Madonna and five hagiographies of female saints, including Saint Columba of Sens, Saint Catherine of Siena, Saint Clare of Assisi, and Saint Justina of Padua. Inspired by this female genealogy, Marinella consistently stressed women’s crucial role in ecclesiastical history, championed female power in both the secular and religious realms, co-opted the lives of holy heroines to shape contemporary discourses on her sex, and invoked the virtue of female saints to rebuke patriarchal stereotypes.

Contemporaneous Network(s)

Marinella maintained close ties with the Venetian Academy. Battista Ciotti, the Academy’s official printer, was her regular publisher, and she dedicated The Nobility and Excellence of Women to Lucio Scarano, the Academy’s secretary. Numerous poetic exchanges and prefatory sonnets to her works attest to her connections with several writers, including the poets Celio Magno (1536–1602) and Giuseppe Policreti, as well as medics and philosophers, such as Leone Bonzio and Teodoro Angelucci. Although Marinella and the contemporary Venetian writer Arcangela Tarabotti–another powerful voice in the debate on women–shared both geographic proximity and political concerns, there is no evidence that the two women ever met. Nonetheless, Tarabotti acknowledged Marinella as a paragon of moral and artistic excellence, and Marinella contributed an introductory sonnet to one of Tarabotti’s works, suggesting mutual recognition, albeit at a distance.

less

Significance

Works/Agency

Lucrezia Marinella was one of the most prolific female writers of early modern Italy, distinguished by the remarkable range of literary genres she explored. Her writings include a mythological-allegorical epic, Amore innamorato et impazzato (Love Enamoured and Driven Mad, 1598); a pastoral novel, Arcadia felice (Happy Arcadia, 1605); a series of moral-allegorical reflections on Luigi Tansillo’s Le lagrime di San Pietro (The Tears of Saint Peter, 1606); an epic poem, L’Enrico, overo Bisantio acquistato (Enrico; or, Byzantium Conquered, 1635); two treatises, La nobiltà et l’eccellenza delle donne (The Nobility and Excellence of Women, 1600) and Essortationi alle donne e a gli altri se saranno a grado (Exhortations to Women, and to Others if They Please, 1645); and a collection of devotional lyrics, Rime sacre (Sacred Rhymes, 1603). Marinella’s favoured genre was hagiography–the lives of the saints. Her first published work was La Colomba sacra (The Sacred Dove, 1595), a poetic tribute to Saint Colomba of Sens. This was followed by Vita del serafico et glorioso San Francesco... Con un discorso del rivolgimento amoroso verso la somma bellezza (The Life of the Seraphic and Glorious Saint Francis... With a Discourse on the Amorous Turn Towards Supreme Beauty, 1597), and La vita di Maria Vergine Imperatrice dell’universo (The Life of the Virgin Mary, Empress of the Universe, 1602), written in a blend of prose and poetry. Her later hagiographic works include De’ gesti heroici e della vita meravigliosa della serafica Santa Caterina da Siena (On the Heroic Deeds and the Wondrous Life of the Seraphic Saint Catherine of Siena, 1624), Le vittorie di Francesco il Serafico. Li passi gloriosi della Diva Chiara (The Victories of the Seraphic Francis. The Glorious Steps of the Divine Clare, 1643), and Holocausto d’amore della vergine Santa Giustina (The Loving Sacrifice of the Virgin Saint Justina, 1648).

Reputation

Lucrezia Marinella actively promoted her work beyond the borders of the Venetian Republic, and her ambition is reflected in the status of the figures to whom she dedicated her writings–ranging from Grand Duchesses and Doges to Popes. She enjoyed considerable esteem in her time: Francesco Sansovino listed her among the three greatest female writers of Venice (alongside Cassandra Fedele and Moderata Fonte), her intellect was celebrated by Girolamo Mercurio and the Lateran canon Pietro Paolo di Ribera Valentiano, while Francesco Agostino Della Chiesa praised her unparalleled eloquence and erudition, and Cristofano Bronzini went so far as to call her the glory of her century. Marinella’s influence extended beyond Italy: to mention but one example, her Nobility and Excellence of Women reached the Dutch scholar Anna Maria van Schurman (1607–1678), who admired the treatise, though she found it too radical. Yet Marinella was not spared the hostility that often beset learned women in the seventeenth century. Her authorship of the The Life of the Virgin Mary (1602) was at one point disputed and the reception of her epic poem was lukewarm – affronts that may have informed the tone of her later treatise, Exhortations to Women and to Others if They Please (1645), in which she expresses her frustration at men’s refusal to support women writers.

Legacy and Influence

After her death, most of Lucrezia Marinella’s writings fell into relative obscurity. Only a few, such as her epic and devotional poetry, continued to circulate in print. In the following centuries, when she was mentioned at all, it was often in dismissive terms, primarily due to her association with the ornate style of Baroque literature. It was not until the late twentieth century, amid a burgeoning scholarly interest in recovering the voices of women thinkers, that Marinella’s work received sustained critical attention for the first time. Since then, research on her corpus has flourished, especially in Anglophone academia, with an expanding body of studies, critical editions, and translations that continue to illuminate new facets of her works and broaden access to her writings. Lucrezia Marinella’s legacy has also extended beyond academic circles, finding resonance in the Italian feminist movement since the 1970s. In the late twentieth century, Anna Jaquinta – a member of the influential collective Rivolta Femminile – sought to recover the voices of women who had been erased from the Italian literary canon. Through this effort, she brought renewed attention to Marinella’s work, alongside that of Moderata Fonte and Arcangela Tarabotti, identifying them as the foremothers of Italian feminist thought. Jaquinta’s research was disseminated by Rivolta Femminile’s own publishing house, circulating these rediscovered figures throughout the feminist movement across Italy. Further evidence of Marinella’s impact is the establishment of the Lucrezia Marinelli Cultural Association in Milan in 1989, founded to promote female-directed films.

less

Context

The Nobility and Excellence of Women is a bold and erudite rebuttal of Giuseppe Passi’s misogynistic I donneschi difetti (Women’s Flaws, 1599), a catalogue of stereotypical accusations against women. Marinella’s treatise emerged from an increasingly inhospitable cultural climate, as misogynistic attitudes gained traction across the Italian peninsula, contributing to the steady exclusion of women from the literary sphere throughout the seventeenth century. Drawing extensively on male philosophers, theologians, and poets–at times to support her argument, but in many cases only to methodically refute their views–Marinella challenges the belief that women are inherently irrational and unfit for public life. Apparent female inferiority, she contends, is not innate but the product of systemic exclusion: men have monopolised education, military training, and power, suppressing women’s potential out of fear of their excellence. Given equal access, she maintains, women’s abilities would not merely rival but surpass those of men.

An important concern in The Nobility and Excellence of Women is the patriarchal distortion of the past by envious male historians. Marinella recognises that the absence of women in historiography is not evidence of their insignificance, but rather the result of deliberate erasure, and corrects the record by assembling a catalogue of illustrious queens, poets, saints, and philosophers, whose achievements testify to the excellence of the female sex.

Marinella was writing in the aftermath of the Council of Trent (1545–1563), which coincided with ecclesiastical efforts to discipline the most potent aspects of female religiosity through measures like the attempted imposition of enclosure for religious women, accusations of counterfeit sanctity, and the ban on vernacular translations of the Bible. In defiance of such restrictions to women’s access to the Scriptures, the first edition of The Nobility and Excellence of Women puts forth a lengthy feminist biblical exegesis: Marinella contends that Eve’s creation from Adam’s rib symbolises refinement rather than subordination; that Adam alone was charged with obeying the divine commandment; and that woman, made in Paradise (unlike man, who was created on earth), is inherently closer to God. The Virgin Mary confirmed woman’s spiritual primacy by redeeming humankind from original sin.

Marinella’s wide-ranging reflections across seemingly disparate subjects ultimately coalesce around a central concern: the inadequacy of all arguments used to bar women from political life.

less

Controversies

Controversy

Marinella’s Exhortations to Women and to Others if They Please (1645), her penultimate work, is a disconcerting treatise that, at first glance, appears to support the conservative norms for women’s conduct she had previously contested. Gone is Marinella’s plea for equal access to education and public life, replaced by a sobering call for women’s withdrawal from intellectual pursuits, advocating seclusion and obedience to husbands. To what extent Marinella’s capitulation should be taken literally is the main question that drives research on this work. Its bitter, disenchanted tone led some scholars to read it as a chronicle of unfulfilled dreams and thwarted ambitions, a rejection of feminism, and a final warning to other women, while others have interpreted it as a continuation of Marinella’s earlier polemic, subversively exposing the rhetorical strategies utilised by men to confine women within domesticity. Whether Marinella’s last treatise should be read as resigned or sarcastic remains an open question.

less

Clusters & Search Terms

Current Identification(s)

Italian literature; Renaissance literature; Early Modern Feminism; Venice

Clusters

Arcangela Tarabotti, Veronica Franco, Luisa Bergalli, Moderata Fonte

Search Terms

Venice; early modern feminism; Italy

References in Existing Schemas

Tarabotti, Arcangela; Fonte, Moderata

less

Bibliography

Primary

Marinella, Lucrezia, La Colomba sacra, poema heroico (Venice: Giovanni Battista Ciotti, 1595).

—, Vita del serafico, et glorioso San Francesco… Con un discorso del rivolgimento amoroso verso la somma bellezza (Venice: Pietro Maria Bertano e Fratelli, 1597).

—, La nobiltà et eccellenze delle donne, et i diffetti, e mancamenti de gli huomini (Venice: Giovanni Battista Ciotti, 1600)

—, La nobiltà et l’eccellenza delle donne, co’ difetti et mancamenti de gli huomini (Venice: Giovanni Battista Ciotti, 1601).

—, La vita di Maria Vergine imperatrice dell’universo, descritta in prosa, et in ottava rima (Venice: Barezzo Barezzi, 1602).

—, Rime sacre (Venice: Collosini, 1603).

—, Arcadia felice (Venice: Giovanni Battista Ciotti, 1605).

—, Vita del serafico et glorioso San Francesco, descritta in ottava rima (Venice: Barezzo Barezzi, 1605).

—, L’imperatrice dell’universo (Bergamo: Comin Ventura, 1605).

—, “Vita del serafico et glorioso San Francesco, descritta in ottava rima.” In Sete canzoni di sette famosi autori in lode del serafico padre San Francesco, e del sacro Monte della Verna (Florence: Giovanni Antonio Caneo e Raffaello Grossi, 1606).

—, La vita di Maria Vergine imperatrice dell’universo… descritta in prosa & poema heroico (Venice: Barezzo Barezzi, 1610).

—, La vita di Maria Vergine imperatrice dell’universo, descritta in prosa, et in ottava rima… aggiuntevi le vite de’ dodici heroi di Christo, e de’ quattro evangelisti (Venice: Barezzo Barezzi, 1617).

—, Amore innamorato, et impazzato, poema… con gli argomenti, et allegorie a ciascun canto (Venice: Giovanni Battista Combi, 1618).

—, La nobiltà et l’eccellenza delle donne, co’ difetti e mancamenti de gli huomini (Venice: Giovanni Battista Combi, 1621).

—, De’ gesti heroici e della vita meravigliosa della serafica Santa Caterina da Siena libri sei (Venice: Barezzo Barezzi, 1624).

—, L’Enrico, overo Bisantio acquistato, poema heroico (Venice: Ghirardo Imberti, 1635).

—, Le vittorie di Francesco il serafico, li passi gloriosi della diva Chiara (Padua: Giulio Crivellari, 1643).

—, Essortationi alle donne et a gli altri se saranno loro a grado (Venice: Francesco Valvasense, 1645).

—, Holocausto d’amore della vergine Santa Giustina (Venice: Matteo Leni, 1648).

Modern Editions

Marinella, Lucrezia, “Vita del glorioso e serafico San Francesco” & “Rivolgimento amoroso dell’uomo verso la divina bellezza.” In Guido Mongini, “‘Nel cor ch’è pur di Cristo il tempio:’ La Vita del serafico e glorioso San Francesco di Lucrezia Marinella tra influssi ignaziani, spiritualismo, e prisca teologia,” Archivio italiano per la storia della pietà, 10 (1997) pp. 359-453.

—, Arcadia Felice, ed. by Françoise Lavocat (Florence: Olschki, 1998).

—, The Nobility and Excellence of Women, ed. and transl. by Anne Dunhill, with an introduction by Letizia Panizza (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999).

—, “The Life of the Virgin Mary, Empress of the Universe.” In Who is Mary? Three Early Modern Women on the Idea of the Virgin Mary, ed. and transl. by Susan Haskins (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008).

—, Enrico, or Byzantium Conquered: A Heroic Poem, ed. and transl. by Maria Galli Stampino (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009).

—, L’Enrico, overo Bisanzio acquistato, ed. by Maria Galli Stampino (Modena: Mucchi, 2011).

—, De’ gesti eroici e della vita maravigliosa della Serafica S. Caterina da Siena, ed. by Armando Maggi (Ravenna: Longo, 2011).

—, Exhortations to Women and to Others if They Please, ed. and transl. by Laura Benedetti (Toronto: Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, 2012).

—, Vita del serafico et glorioso San Francesco; Le vittorie di Francesco il Serafico. Li passi gloriosi della diva Chiara, ed. by Armando Maggi (Ravenna: Longo, 2018).

—, Amore innamorato et impazzato, ed. by Armando Maggi (Ravenna, Longo, 2023).

Online Resources

Deslauriers, Marguerite, “Lucrezia Marinella,” Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy (2024).

Galli Stampino, Maria, “Lucrezia Marinella,” Oxford Bibliographies (2019).

Images

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucrezia_Marinella#/media/File:1601_Marinella_La_Nobilita.jpg

Comment

Your message was sent successfully