Birth

c.1763, Oyster Bay or Jericho, New York

Death

After 1806, Oyster Bay, New York

Liss, or Elizabeth, was born in Oyster Bay, New York, around the year 1763, and was enslaved in the home of Samuel Townsend, whose son Robert Townsend was a key member of George Washington's Culper Spy Ring, a network of spies active during the Revolutionary War. In 1778, the Townsend home became the temporary headquarters of a British commander and early abolitionist named Col. John Graves Simcoe. Simcoe helped Liss to escape in 1779, but she was not freed. Instead, she was re-enslaved in New York City by another British officer.

During the Revolutionary war, Liss had contact with Robert, evidenced by several items he purchased for her which were noted in his ledger book. When her British enslaver was going to evacuate at the war’s end, Liss appealed to Robert to help her stay in New York City. As Robert would later write, the man who currently enslaved her was “about to leave this state on the evacuation by the British.” Robert then added, in reference to Liss, “she not willing to go with him, apply’d to our R.T. to repurchase her, which he did.” Records indicate that Liss was three months pregnant at the time, which undoubtedly was part of her reason for wanting to stay in a familiar and safe place with dependable resources. Though he agreed to purchase Liss to help her remain in New York, Robert had begun to have moral objections to the institution of slavery. He hired a white housekeeper named Polly Banvard, perhaps so that Liss would not have to perform any arduous tasks, and brought Liss into his household. Six months later she gave birth to a son named Harry, who Robert later described as mixed race. When Harry was six months old, Robert was approached by a middle aged woman both he and Liss knew named Ann Sharwin. Ann’s husband had suddenly died, and she was interested in purchasing both Liss and baby Harry. Robert (with Liss’s approval) agreed, and Ann promised Robert she would not take Liss and Harry out of Manhattan or sell them to anyone else. However, when Ann remarried a wealthy merchant named Alexander Robertson one year later, the couple fought, perhaps about Liss, and the union was dissolved within a month. Out of spite, greed, or both, and unbeknownst to Robert, Alexander sold Liss south to Charleston, South Carolina, and kept two-year-old Harry in his household in New York City.

In Charleston, 1785, Liss was enslaved by a violent man named Richard Palmes who had been the instigator of the Boston Massacre of 1770. After two years, Robert, who had joined an early anti-slavery group called the New York Manumission Society, discovered what had happened. He brought Liss’s son Harry to his parents' house in Oyster Bay and worked to bring Liss back to New York. In the end, she was likely smuggled back, due to a new law prohibiting the importation of slaves into New York.

For the next sixteen years, records indicate she lived in a state of quasi-freedom, working as a paid servant but without any official freedom papers. Finally in 1803, at about age forty, Liss obtained her legal freedom and lived her remaining years in the village of Oyster Bay. The details discovered about Liss’s life help to represent the forgotten lives of many enslaved people of color who lived and labored in New York during the Founding era.

Personal Information

Name(s):

Liss, or Elizabeth

Date and place of birth:

c. 1763, Oyster Bay or Jericho, New York

Death and place of death:

Liss died sometime after 1806 in Oyster Bay, New York.

In the Townsend family cemetery, near the carved formal headstones, is a grouping of unmarked natural fieldstones believed to mark the graves of enslaved people.

Family

Siblings:

Liss had a younger sister named Hannah (c. 1765 – after 1803), who was also enslaved by the Townsends. Hannah had two children: a daughter named Violet (Apr. 29, 1787–Jan. 1795) who died at age eight, and a son named John (c. Feb. 19, 1803). A letter written on March 22, 1787, when Hannah was eight months pregnant with Violet, claims Hannah was "offered her freedom which she declined taking." This offer of freedom may not have seemed practical to Hannah, considering her advanced pregnancy, and the likelihood that she had limited resources to care for herself and a newborn. Six years after Violet's death, Hannah gave birth to John. Hannah was legally freed in Oyster Bay on September 3, 1803, with her sister Liss. Her infant son, John, also gained his freedom on the same day through an unusual legal loophole called the Child Abandonment Program.

Mother:

Pender (dates unknown). Members of the Townsend family of Jericho and Oyster Bay enslaved Pender. Subsequently, Pender’s children were also enslaved by the Townsends. Children were enslaved at birth to those who enslaved their mother, lasting for the child’s entire life, unless the laws changed, the enslavers decided to free them, or they escaped. A 1739 record of Samuel Townsend’s grandfather regarding inheritance of his enslaved people instructs that they were “to be divided as the stock of cattle, sheep, horses and swine are—in the same manner and proportion.”

Father:

No information has been found to identify Liss's father. Because ownership of enslaved children was determined through the mother, it is often difficult to find records of enslaved people’s fathers.

Marriage and Family Life:

At about age 20, Liss gave birth in New York City to a son named Harry (Feb. 19, 1783). While the identity of Harry's father is unknown, Harry is described as "mulatto," or mixed-race, opening the possibility that either Robert Townsend or her British enslaver in NYC was Harry’s father. When Harry was six months old, he and Liss were sold to a widow in Manhattan named Ann Sharwin, who promised Robert Townsend she would not resell the mother and child to anyone or move away without informing him. However, when the widow remarried a year later, Liss was sold south to Charleston, South Carolina, and separated from Harry, who remained enslaved in New York City. At age four, Harry was taken from the house in Manhattan and brought to the Townsend home in Oyster Bay, where he remained enslaved until adulthood. It is presumed that when Liss returned to Oyster Bay in 1787, she was reunited with Harry.

Education

Short version:

Unknown.

Long version:

Enslaved people in New York were not prohibited by law from becoming educated, but it was uncommon. However, records of the Townsend family show two instances of the Townsends selling spelling books to enslaved people living elsewhere in Oyster Bay. Liss’s enslavers formally schooled both their sons and daughters and highly valued education, so perhaps Liss had some level of literacy.

Religion:

Liss is listed as a member of the Baptist Church of Oyster in 1789 and again in 1806. At a later time, the word “dead” was added, indicating that Liss belonged to this congregation for the remainder of her life.

Transformation(s):

Liss was born into a system of slavery that controlled many aspects of her life through extreme punishments, such as public whipping, branding, collaring, and death for those who tried to escape. Despite these threats, Liss showed incredible agency and bravery by escaping on May 18, 1779, with a British regiment called the Queen’s Rangers, aided by their commander Col. John Graves Simcoe.

Re-enslaved for the remainder of the war in Manhattan, it is possible that Liss aided in the collection of intelligence for the American effort through her association with the spy Robert Townsend. If Liss was involved, she risked punishment from the British, which could have resulted in death by hanging or, in the case of women, being burned alive. At the war’s end, now three months pregnant, Liss asked Robert to purchase her so that she might stay in New York City. At a time when over 3,000 formerly enslaved Black people sailed to Nova Scotia in search of freedom, Liss may have chosen to stay in New York because of nearby family or to provide a more stable home for her child.

There are indications that Liss was a social person who was unafraid to associate and converse with powerful white people. When she was sold south to Charleston, a letter indicates she commanded a “great price.” It appears Liss was valuable for reasons other than the ability to perform household work. While most enslaved mothers were sold with their young children as a unit, Liss was purchased in Charleston by herself, and sold to a violent man named Richard Palmes who was prone to bankruptcy and known to indulge in the purchase of luxury goods he could not easily afford. In the case of Liss, Palmes could not afford to purchase her outright, taking out a mortgage or bond for the remainder due. Few details of her enslavement in Charleston and return to Oyster Bay are known, but Liss likely endured significant trauma. Despite a lifetime of struggles and barriers, Liss eventually gained her legal freedom at about age forty.

Contemporaneous Network(s):

At least twenty Black individuals were enslaved alongside Liss in the household of Samuel Townsend, including her sister Hannah, her daughter Violet, Susannah (c. -1779), her son Jeffery (July 7, 1769), Susan, her daughter Catherine (c. Sept. 1772), Lilly (Sept. 1774 – after 1796), her son Nicholas (June 16, 1792), an unnamed child born to Lilly (c. Feb. 3, 1794), her son William (Dec. 11, 1796), Jane, her husband Gabriel Parker, their daughter Rachel Parker (Sept. 3, 1786), John, Jacob, Priscilla (c. 1763), her son Amos Burling (c. 1795 – after 1830), and an unnamed man captured at sea and purchased by Samuel at a privateer auction on March 10, 1749. Dr. James Townsend of Jericho and his estate also enslaved Hannah’s son John (c. 1803), Sarah (c. Feb. 1779), and another man named John (c. Oct. 1785). Jane and Gabriel (who later took the last name Parker) were given to Solomon Townsend, the oldest son, as his wedding present in 1782. Their seven children, also enslaved by Solomon Townsend, were Rachel Parker (Sept. 3, 1786), Susanah (June 8, 1788), Mary Ann (c. 1790), Nancy, Kate, Jim, and Josh, all four born after 1795. In the mid-1790s, Gabriel became free and worked for the family in Oyster Bay and then for Solomon in New York City at an anchor shop. As part of his wages, Gabriel was given a room in the shop cellar and was permitted to bring Jane and the children to live with him, though they were all still enslaved. During the 18th century, sixteen percent of the population of Oyster Bay were enslaved people of color. A smaller community of free Black people also lived in the town, especially the Gall or Gaul family, descended from Tom Gall, the first known slave freed on Long Island in 1685. Tom Gall married a free Black woman named Mary and purchased and later freed his daughter’s husband, Obed. Before his emancipation, Tom Gall labored on the property that would become the home of Samuel Townsend where Liss was enslaved.

less

Significance

Contemporaneous Identifications

Reputation:

Liss’s life was not recognized or studied until 2004. The home of Samuel Townsend was preserved as a site of historical significance of the white family by the Daughters of the American Revolution and in the 1950s by the Town of Oyster Bay with the establishment of a house museum called Raynham Hall. Though the mission was to interpret the lives of those who had lived there, only the white lives were represented. These interpretations of the family history made no mention of slavery at the site, though documents owned by the museum did include records of enslaved people. Raynham Hall purchased a Bible auctioned by descendants of the Townsend family in 2004 that listed the names of seventeen individuals enslaved by the Townsends. Liss was not listed, but subsequent research led to the discovery of her story.

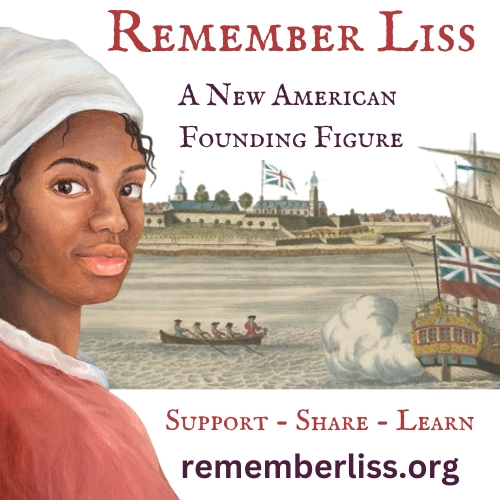

Legacy and Influence:

A non-profit organization called Remember Liss was founded in 2022 with the mission to share information as it was recovered about her life and times with the community. Two book have been published about Liss. Authored by Claire Bellerjeau and Tiffany Yecke Brooks, they are titled Espionage and Enslavement and Remember Liss: The Remarkable True Story of One Woman's Enslavement and Freedom in New York.

less

Controversies

Controversy:

For over 150 years, writings and research about the Townsend family did not include information about slavery at the site. Early histories of the family wrongly identified them as Quakers, with the erroneous implication that Quakers did not own slaves. This misidentification continues to be repeated in books and in film, despite documents showing that the Townsends were Baptists. In the 1930s, an author and historian named Morton Pennypacker, who had devoted much of his career studying the Culper Spy Ring, uncovered an account of two enslaved Black women in East Hampton who attempted to thwart the Benedict Arnold treason plot. Pennypacker wrote about this incident, but claimed the event occurred in the Townsend home in Oyster Bay and attributed the deed to the white sister of the spy Robert Townsend, a teenaged girl named Sally. Later historians and authors retold the whitewashed version, including a book titled Treason Stops at Oyster Bay, which is still taught to fourth graders in local schools. An official state historic marker outside the Raynham Hall Museum mentions this erroneous legend, though museum staff no longer include this in their programming and the story of those enslaved on the site is now part of the interpretation.

New and Unfolding Information and/or Interpretations:

Liss’s story is new to the public, based on 18 years of ongoing research. Advances in technology during this research were vital; archives began to make scanned images of documents more accessible, and early newspapers became digitized.

less

Clusters & Search Terms

Current Identification(s):

Black Studies

Clusters:

Phyillis Wheatley, Jupiter Hammon, Crispus Attucks, Tom Gall

Search Terms:

Culper Spy Ring, Robert Townsend, 18th century espionage, Agent 355

References in existing schemas:

None

less

Bibliography

Sources:

Primary (selected):

Bellerjeau, Claire and Tiffany Yecke Brooks. Espionage and Enslavement in the Revolution: The True Story of Robert Townsend and Elizabeth. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2021.

Bellerjeau, Claire and Tiffany Yecke Brooks. Remember Liss. New York, NY: Remember Liss, Inc., 2023.

Archival Resources:

New York Archive’s “Consider the Source” teaching platform features over 100 primary documents related to Liss.

Web Resources:

https://www.espionageandenslavement.com/

https://raynhamhallmuseum.org/slavery-at-the-townsends/

Images:

Painting: “Liss” by Lindsey Levine. Collection of Claire Bellerjeau. Permission from Claire Bellerjeau.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully