Birth

1637, in Titchfield, Hampshire

Education

UnknownDeath

September 29th, 1723 in London, UKReligion

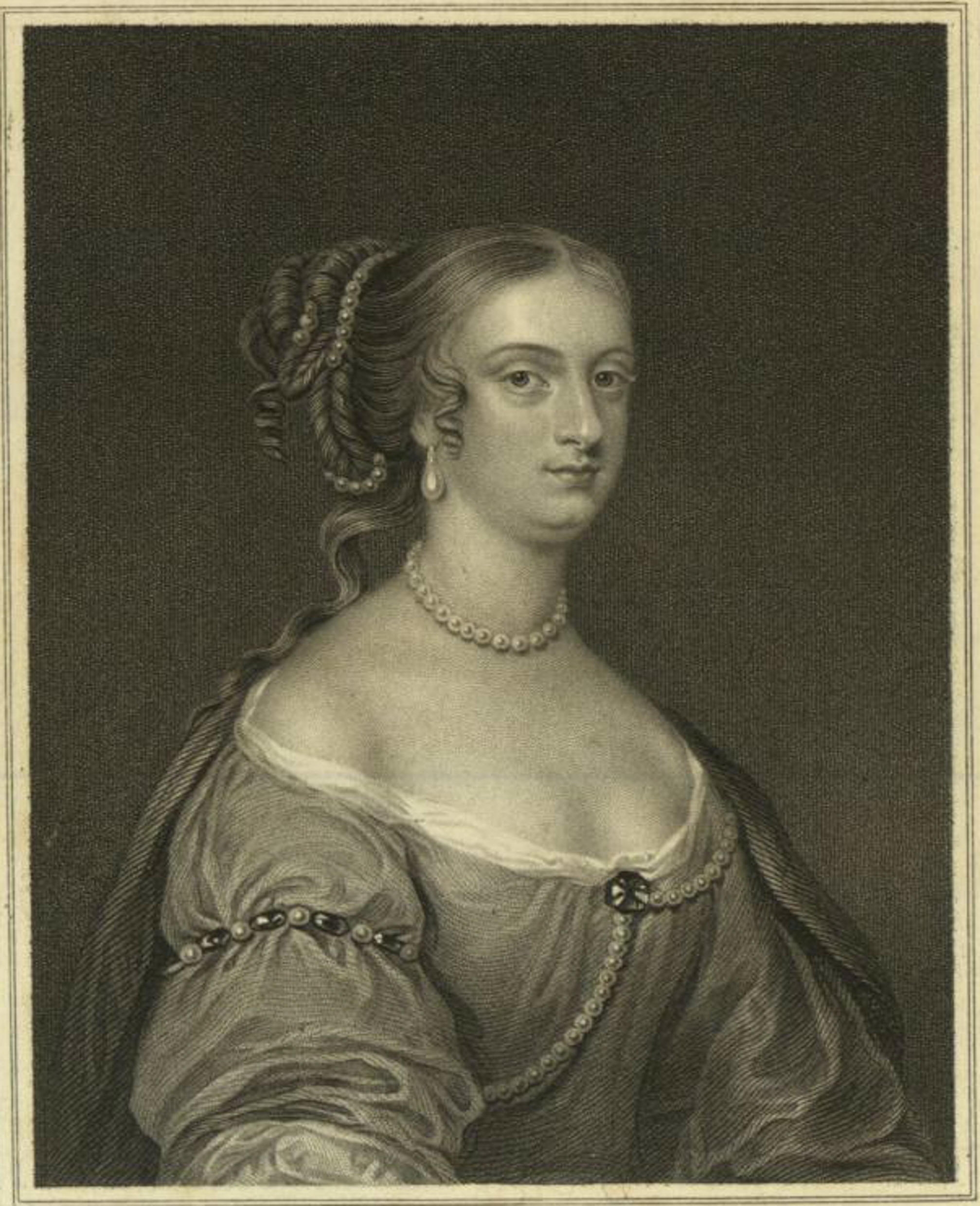

Anglican, ProtestantLady Rachel Russell was an author and avid letter writer, many of which were published posthumously in 1772. She was a noble woman who played a public and active role in trying to mitigate her husband's punishment and the damage to his reputation when he was arrested and executed for his participation in the Rye House Plot (1683). Through the content discovered in the publication of her letters and the political actions Lady Russell took throughout her widowhood, she has been celebrated as a highly accomplished and virtuous woman.

Personal Information

Name(s)

Lady Rachel Russell, née Wriothesley.

Date and place of birth

1637, in Titchfield, Hampshire (She was baptized on September 19).

Death and place of death

September 29, 1723, London

In the Weekly Journal, or British Gazeteer, October 5, 1723, her death is thus recorded: “The Right Honourable the Lady Russell, relict of Lord William Russell, died on Sunday morning last, at 5 o’clock, at Southampton House, aged eighty-six, and her corpse is to be carried to Chenies, in Buckinghamshire, to be interred with that of her husband” (qtd. In Berry 1819, 152).

Family

Mother: The French Huguenot Rachel de Massue de Ruvigny de la Maison Fort (1603-1640), “la belle et vertuese Huguenotte.” She descended from a bourgeois family of Abbeville (France). However, her brother Henri elevated the family’s position due to his reputation among both Huguenot and court circles (Schwoerer 1988, 6-7). In 1673 Henri was appointed ambassador from Louis XIV to the English court; hence, thanks to his frequent journeys to England, Lady Rachel had a close relationship with her uncle, and then his son, also Henri, who became first earl of Galway, after fighting under the prince of Orange.

Father: Sir Thomas Wriothesley, Fourth Earl of Southampton (1607-1667), English statesman, Lord High-Treasurer (1660-67), a faith supporter of the royal cause. He received the Garter, the highest order of English knighthood (Schwoerer 1988, 27). It was the great-grandfather of Lady Rachel’s father who established the family’s landed wealth and tradition of political service under Henry VIII.

Lady Rachel’s parents met in Paris and it was the first marriage for him, while Rachel de Masue had been a widow for nine years. They had two daughters, Elizabeth and Rachel. When Rachel’s mother died in 1640, her father married Lady Elizabeth Leigh and had another daughter, Elizabeth. He married for the third time with Lady Frances Seymour and they had no children.

Hence, Rachel had one sister, Elizabeth (1636-1680), Viscountess Campden, wife of Edward Noel, 1st Earl of Gainsborough; and one half-sister, also called Elizabeth (1646-1690), who married twice, firstly to Joceline Percy, 11th Earl of Northumberland, whom she bore an only surviving child, heiress to the vast Percy estates, and secondly to Ralph Montagu, 1st Duke of Montagu.

Marriage and Family Life

First husband: Francis Vaughan, Lord Vaughan, (c. 1638-1667), member of Parliament for Carmarthershire (Wales). He married Lady Rachel in 1654. She had a child who “only lived to be baptized” (Some Account, p.18). Lady Vaughan retained the name of her first husband while married to her second husband, until Lord Russell, after the death of his elder brother in 1678, succeeded to his title (Berry 1819, 161).

Second husband: William lord Russel: William Russell, Lord Russell (1639-1683), English politician, leading member of the Country Party, forerunners of the Whigs. He was one of the aristocratic members of the Country Party who participated in the Rye House Plot (1683), an alleged Whig conspiracy to assassinate or mount an insurrection against Charles II because of his pro-Roman Catholic policies. The plot drew the name from Rye House at Hoddeston, Hertfordshire, near which Charles was supposed to be killed. The facts remain cloudy, but there were meetings where they discussed how to get rid the country of Charles and his brother.

On 26th June Russell was arrested and on 13th July tried and found guilty of high treason. He was sentenced to death and executed on 21st July 1683.

Because the charges against Russell were never conclusively proved, he was lauded as a martyr by the Whigs, who claimed that he was put to death in retaliation for his efforts to exclude James from succession to the throne (Schwoerer 2009).

They married in 1669 and were a loving couple until his tragic death in 1683. They had four children:

Anne (1671-2), died within four months.

Rachel (1674-1725), married William Cavendish, Second Duke of Devonshire, by whom she had five children.

Katherine (1676-1711), married John Manners, Second Duke of Ruthland, by whom she had nine children.

Wriothesley, Second Duke of Bedford (1680-1711), married Elizabeth Howland, by whom he had six children.

Education

There is no evidence about her education in any document or letter; however, as she belonged to a noble family and she also married to husbands of noble origin, Lady Rachel must have had the suitable education for a lady of her rank at that time.

Religion

Her mother belonged to a French Huguenot family and Lady Rachel defended their cause. As for her father, he followed Puritan faith and was tolerant with dissenters. Her religious ideas were Anglican, but highly influenced by Nonconformity.

As a faithful supporter of her second husband’s cause, Lady Rachel can be defined as a true Protestant, who was against both Charles II and his brother, the Duke of York, as they were accused of trying to establish once again the Catholic faith in England. She even was acquainted with Queen Mary II and her husband, the prince of Orange, who lamented deeply Lord Russell’s death: a “blow to the best interest of England [and] the Protestant religion” (qtd. in Schwoerer 1988, 160).

Transformation(s)

The execution of her husband changed dramatically her personal life, but she also started a campaign, by means of letters to those who supported her husband’s ideals, to maintain his memory and to transform him into a Protestant martyr.

Contemporaneous Network(s)

With her female relatives: sisters and sisters-in-law, daughters and daughter-in-law.

Letters to Queen Mary.

With her religious friends and advisors: John Tillotson, archbishop of Canterbury, Gilbert Burnet, bishop of Salisbury, and Doctor Fitzwilliam, former chaplain to Lady Rachel’s father.

less

Significance

Works/Agency.

Lady Rachel’s letters, which were included in both these collections:

- Letters of Lady Rachel Russell; from the manuscript in the library at Woburn Abbey. To which is prefixed, an introduction, vindicating the character of Lord Russell against Sir John Dalrymple, &c. (London: Edward & Charles Dilly, 1773).

- Some account of the life of Rachael Wriothesley Lady Russell / By the editor of Madame du Deffand's letters. Followed by a series of letters from Lady Russell to her husband, William Lord Russell, from 1672–1682; together with some miscellaneous letters to and from Lady Russell. To which are added, eleven letters from Dorothy Sidney Countess of Sunderland, to George Saville Marquis of Hallifax in the year 1680. Published from the originals in the possession of His Grace the Duke of Devonshire (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown [etc.], 1819).

Lady Rachel was, like so many active-minded women of her times, a voluminous letter writer. These letters were extant in Woburn Abbey, one of the country houses of Russell family and Dukes of Bedford y Bedfordshire. They were then copied by Thomas Sellwood from the original manuscripts and published by him with permission of the Duke of Bedford in 1772. However, some difficulties might arise given that the dedication by Sellwood to the Duke of Bedford dates 1748. These letters by Lady Russell are considered to “have the charm of naturalness and the distinction of noble nature” (Schwoerer 2009). Among the letters, there are those addressed to her family and other relevant people such as Archbishop Tillotson, Dr. Fitzwilliam, the princess of Orange, along with some letters addressed to her by Archbishop Tillotson. Years later, in 1819, another series of letters was published, which were in possession of the Duchess of Devonshire, her only surviving daughter, and were published by her successor from the Cavendish family. They were more personal and only addressed to her husband and doubtless with a different tone and style: “These letters are written with such a neglect of style, and often of grammar, as may disgust the admirers of well-turned periods” (Berry 1819, 20). These letters and other miscellaneous letters to and from Lady Russell were edited, as it can be read on the titlepage, by “the editor of Madame du Deffand’s letters”, who has been identified as Mary Barry. In her edition several annotations to the letters were added to explain the characters and facts mentioned in them. There are subsequent editions of Lady Russell’s letters which include all the above-mentioned ones, even published in the USA (Martin 1854), and collections of letters in which some letter of hers are included.

Reputation

When alive and until her husband’s trial, Lady Rachel seems to have led the life of a noble woman, taking care of her family and household. However, when her husband, Lord Russell, was imprisoned and judged, her active role was publicly recognized, since she was totally involved in trying to obtain a mitigation of punishment or at least a respite for him. She even acted as a secretary for Lord Russell during the trial by keeping records.

In Waisman’s opinion (2006), during Lord Russell’s confinement, his position was not certain, he was ambiguous about what drove his actions: was he a traitor or a patriot? The cause was Russell’s insistence on the legitimacy of resistance against the king, if there were genuine reasons for that. However, this collided with subjects’ obedience to their sovereign.

Once he was executed, Lady Rachel used her grief at her loss of such a husband, who was a paragon of virtue, to shift the previous debate about Lord Russell’s ambiguous political position. By means of her letters, which circulated among Whig circles, she memorialised Lord Russell and attributed to him a political philosophy. He was a believer in resistance theory, which was later on the justification for Prince of Orange’s actions and his accession to the English throne. Most importantly, Lady Rachel was well known during her lifetime, and indeed was described by a contemporary as “One of the best of women” (Schwoerer 1988).

After the Restoration, although she maintained her correspondence with relevant religious and political figures, Lady Rachel concentrated on taking care of her family. She arranged advantageous marriages for her children and she also acted as a wise estate administrator and supervised all her properties.

After her death, she disappeared for a time, until the publication of her letters posthumously in 1772. From this moment on she was often discussed in diverse types of writings, and her biography was frequently published, particularly in 19th century compendia of celebrated women (Booth 2004). These texts provided the portrait of an ideal woman: a virtuous and pious woman, an affectionate daughter, wife and mother, who was able to endure life’s trials with fortitude, values which are wholly in agreement with those of women typically portrayed in the “female worthies” kind of compilation, and with the type of historical characters that the habitual readers of these collections, women, seemed to enjoyed the most. Indeed, the attribute of fortitude has been a commonplace in Lady Rachel’s numerous biographical accounts, and it has been exploited by her biographers as a combination of maternal and family duties with courage and dignity (Culley 2014, 38).

less

Bibliography

- 1773. Letters of Lady Rachel Russell; from the manuscript in the library at Woburn Abbey. To which is prefixed, an introduction, vindicating the character of Lord Russell against Sir John Dalrymple, &c. London: Edward & Charles Dilly.

Berry, Mary. 1819. Some account of the life of Rachael Wriothesley Lady Russell / By the editor of Madame du Deffand's letters. Followed by a series of letters from Lady Russell to her husband, William Lord Russell, from 1672–1682; together with some miscellaneous letters to and from Lady Russell. To which are added, eleven letters from Dorothy Sidney Countess of Sunderland, to George Saville Marquis of Hallifax in the year 1680. Published from the originals in the possession of His Grace the Duke of Devonshire. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown [etc.].

Booth, Alison. 2004. How to Make it as a Woman. Collective Biographical History from Victoria to the Present. Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press.

Culley, Amy. 2014. “Reading the Past. Women Writers and the Afterlives of Lady Rachel Russell”. In Historical Writing in Britain 1688-1830. Visions of History, edited by Ben Dew and Fiona Price, 34-52. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Lasa Álvarez, Begoña. 2014. Annotations for Lady Rachel Russel. In Female Biography; or, Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women, of All Ages and Countries. Alphabetically Arranged. Vol. VI, edited by Gina Luria Walker, 617-620. London: Pickering & Chatto.

Martin, John, ed. 1854. Letters of Rachel, Lady Russell. Philadelphia: Parry and M’Millan.

Schwoerer, Lois G. 1988. Lady Rachel Russell “One of the Best of Women”. Baltimore & London: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

--- 2009. “Russell, William, Lord Russell [called the Patriot, the Martyr] (1639–1683)”, ODNB. Oxford: Oxford University Press, online ed. [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/24344, accessed 28 Sept 2012].

Spongberg, Mary. 2002. Writing Women’s History since the Renaissance. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Wiseman, Susan. 2006. Conspiracy and Virtue: Women, Writing, and Politics in Seventeenth-Century England. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully