Birth

Unknown. Most popular sources date her birth to c. 1258.

Education

Chose Namdev as her guru (teacher/master)

Death

March 6th, 2022Religion

HinduismJanabai was a poet from Maharashtra, India. She wrote around 340 Marathi abhangas (poems). Her poems include stories of Krishna’s birth, childhood, and play, along with a story about all the ten avatars (reincarnations) of Vishnu. Her works also tell the story of ancient Indian King Harishchandra and demonstrate awareness of the story of Pundalik, Vitthala’s ultimate bhakta (devotee). Alongside such stories, Janabai’s poetry shows a deep and philosophical understanding of the world. One finds her contemplating what it means to be a saint and grappling with the struggle of bhakti. Her poems convey a deep understanding of the concept of shunya (zero), of ganit (mathematics), and of her own social realities. In some of the poems, she also speaks of learning to write. Janabai also appears to be the first biographer of Namdev, the poet-saint who chose as her guru.

Personal Information

Name(s)

Janabai, Jani, Janai.

Jana or Jani in Marathi means “people.” It also connotes “birth” or “creation.”

Date and place of birth

The date of Janabai’s birth cannot be said with certainty, but most popular sources date her birth to c. 1258, except for one unpublished thesis (Sinha), which dates it to c. 1270. She was born in the village of Gangakhed in Maharashtra, India.

Date and place of death

She died in c. 1350. In public memory, she is said to have taken Samadhi, the highest meditative state an individual can achieve, in front of the Vitthala temple at Pandharpur in Maharashtra.

Family

Mother

Karund. She is known for having been devoted to her husband and to Vitthala.

Father

Damā. He is associated with the shudra varna (lower caste group, who were usually peasants or aristans) and was a Vitthala (Vitthal is a reincarnation of Vishnu) devotee.

According to legend, Karund and Damā did not have any children. So, they prayed to Vitthala. One-night, Vitthala came in Damā’s dream and said to him that he would have a daughter and that he should name her Jana and give her to Damāshet (Namdev’s father). She would bring salvation and fame to the family.

Marriage and Family Life

Janabai never married. At the young age of 7, she started living with poet-saint Namdev’s (c. 1270 – c. 1350) family.

Education

Janabai did not receive a formal education. However, she chose Namdev to be her guru (teacher/master) and paid homage to him through the signature in her poems, which uses the words Mhane Namyachi Jani, that is, “Says Namdev’s Jani.” Her associations with Namdev possibly instructed her in mythology and spirituality.

Suggesting the saint’s familiarity with Hindu epic, Janabai’s poems contain references to stories from the Mahabharata, such as Draupdi’s vastraharan (disrobing) and the story of Draupadi’s Akshayapatra (a mythical pot from which food cannot be exhausted) and the Pandavas hosting of sage Durvasa in the forest, which is titled Thalipak. She is also credited with the development of the charitra (profile or biography) of her contemporary saints, such as Namdev and Sena Nhavi (n.d.) along with singing the praises of Jnaneshwar (c. 1275–c. 1296). Her poems also include stories of Krishna’s birth, childhood and play, along with a story about all the ten avatars (reincarnations) of Vishnu. Her works also tell the story of ancient Indian King Harishchandra and demonstrate awareness of the story of Pundalik, Vitthala’s ultimate bhakta (devotee). Alongside such stories, Janabai’s poetry shows a deep and philosophical understanding of the world. One finds her contemplating what it means to be a saint and grappling with the struggle of bhakti. Her poems convey a deep understanding of the concept of shunya (zero), of ganit (mathematics), and of her own social realities. In some of the poems, she also speaks of learning to write.

Religion

Hinduism. She was posthumously canonised into a sampradaya (community/sect/cult) called the Varkaris and became Sant Janabai. The regional and vernacular nature of this community and its literature gave voice to the underrepresented cultures and to marginalized populations such as women and lower caste people. Jani’s position as a shudra women makes her a good representative of the philosophy of the Varkari sect.

less

Significance

Works/Agency

Around 340 Marathi abhangas (poems) that are attributed to Janabai are found as part of the Namdev Gatha, which is the story of Namdev. An early version of the Namdev Gatha can be dated to c. 1581. Later, the hagiographer and kirtankar Mahipati (c. 1715 – c. 1790) wrote the first biography of Janabai in his Bhaktavijay in c. 1762. In public memory, it is difficult to make a distinction between what Janabai wrote and what was written about her, mostly because Mahipati also borrows some stories from her poems. Janabai also appears to be the first biographer of Namdev as she bears witness to Namdev’s journey, family and kirtan, a devotional communitarian experience in which one or more performers (singers, musicians) recite a narrative or song, and sings/writes about them.

Reputation

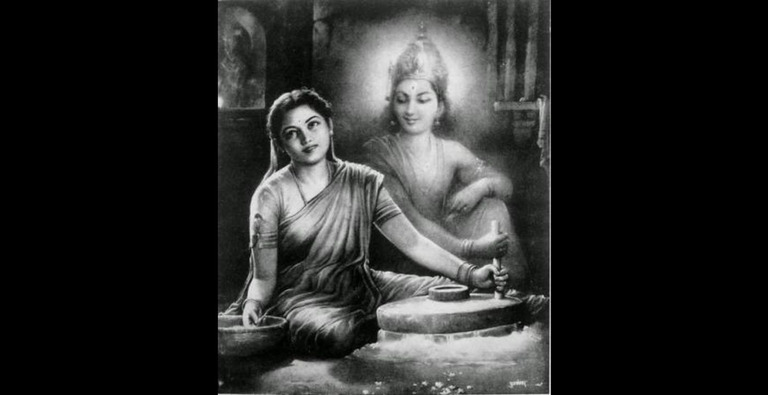

Both Janabai’s poems and her biography by Mahipati suggest that Vitthala liked spending time with Janabai and that he held her in high regard. However, this relationship often remained a secret. One poem describes how Vitthala came to meet her using the excuse of grinding or domestic work, but his actual purpose was to listen to her emotive songs and sing with her. Another poem describes how Gonai (13th-14th century), Namdev’s mother, hears another voice of a woman, as Jani is grinding. She thinks Jani hired someone to help her with the household chores and starts scolding her. Then, the other woman reveals herself to be Vithai. Seeing this, Gonai falls at Vithai’s feet and asks for forgiveness. Another poem speaks of the spiritual value of Jani’s words, such that Vitthala takes notes as she speaks. There are many stories of poets who receive a scribe from the god, but, here, it’s the god who becomes the scribe for Jani.

Another story describes how a heavy rainstorm strikes Namdev’s house breaking the roof. Vitthala comes and repairs it. Then, he sits down to eat with Namdev and his family. Jani is excluded from this gathering. She grieves that she has been abandoned by her god. Vitthala cannot eat the food served by Rajai (13th-14th century), Namdev’s wife, and Gonai, who sit at his feet and are thus blessed. Gonai gives the food left by Vitthala to Janabai. He then goes to Jani’s hut and eats that same food with her.

Mahipati’s narrative makes Janabai’s journey dependent on Namdev. However, her poems show a variety of conflicting emotions, which may or may not depend on Namdev; in the contemporary oral tradition of rural Maharashtrian women, Janabai is quite independent of Namdev.

Transformation

According to Mahipati, Janabai came to live in Vitthala’s city, Pandharpur with Namdev’s family in her early childhood. He mentions that Janabai had come to the Pandharpur temple with her parents, and once there she demanded that she be left at the temple because her heart was with Vitthala. Namdev found her and asked who she was. She answered saying that she had no one other than Vitthala. Taking pity on her, Namdev brought her home with him, following which, Janabai started referring to herself as Namdev’s dasi and considering Namdev to be her only kin. In this biographical account, Janabai cites episodes from mythological stories to argue that she was destined to be Namdev’s dasi, given that she was a dasi to other reincarnations of him. In this sense, Janabai’s journey to the divine begins with her discovery by Namdev, as per Mahipati.

A key motif in Janabai’s poetry is domestic space. In this context a feminine version of Vitthala’s name appears: Vithabai or Vithai. Vithai comes to meet Jani in Namdev’s house. This divine presence not only helps Jani with household chores but also pampers Jani by bathing her and braiding her hair. Jani treats Vitthala as her mother and addresses and imagines him as Vithabai, which is the god’s name in feminine form. Through this treatment, Janabai constructs an image of a god who reflects her own reality (Vanita). Thus, it is not only the human who is transformed to meet the god, but also the god who becomes feminized to meet the human woman.

New and unfolding information and interpretations

Janabai is usually called a maid owing to her frequent usage of the word dasi to refer to herself. Her poems and Mahipati’s biography suggest that she did household work in Namdev’s house and was treated in a lowly manner. However, the word dasi differs from its masculine counterpart das, which not only means a servant but also a philosopher or sage according to Molesworth’s Marathi and English Dictionary. This second meaning—a philosopher or sage—is not applied to a woman who calls herself dasi. Janabai is hence stripped of the scholarly aspect of her personality by employing the servant or maid meaning of the word dasi.

By acting as Namdev’s disciple or dasi, Janabai becomes part of the Guru-shishya tradition of ancient India where a student (generally male) lived at the teacher’s house or aashram and helped with the household work in order to get an education. Janabai’s poems suggest that she was deeply invested in learning about the secrets of the world, demonstrating a scholarly aspect to her work that has been side-lined in her tittle as dasi.

Janabai’s popular representation also removes any sexual connotations from her persona. She is often shown as an asexual abandoned child. However, in academic circles, her most translated poem is Doicha Padar aala Kandhya vari (The veil has come off the shoulder). In this poem, she calls herself a prostitute who has come to the market bare-headed, has no shame and is going to sell herself. In other poems, she also calls herself a randki (widow) or vesva (prostitute), indicating that sexuality is equally a part of her identity.

Contemporaneous context

Thirteenth-century Maharashtra was rife with linguistic and religious movements. During this time, the Varkari Sampradaya came to exist through the songs of Sant Jnaneshwar and Namdev. In this Hindu religious sect, Jnaneshwar, an outcast Brahman saint in popular public memory, was associated with the Jnana marg, the intellectual path towards spirituality, whereas Namdev, a lower caste figure, was associated with Bhakti marg, the devotional path towards union with the god. Each holy figure composed literature in Marathi, the vernacular language, as opposed to Sanskrit, which was the language of the court and of holy texts that were mostly accessible by upper caste Brahmins. By singing devotional songs in a popular, local, and vernacular language, the Varkaris resisted the authoritative nature of Sanskrit and Brahminism. Marathi bhakti of Vitthala can be largely linked with the Varkari tradition. This bhakti takes the form of sakhya bhakti, which is friendship with the god, or vatsalya bhakti, which is parent-child relationship between the god and devotees. The word Varkari, which means the ones who go on pilgrimage regularly, derives its meaning from two words: vari (repeated journeys or movement) and kari (doing and also the one who does). This meaning of varkari is still prevalent in Maharashtra keeping the Sampradaya alive.

Along with the Varkaris, the Mahanubhavs and the Nath Sampradaya were equally part of the linguistic and religious movements of the 12th and 13th century Maharashtra. The mahanubhav sect was founded by Chakradhar Swami and worships Krishna. The Nath Sampradaya is a Shiva worshipping sect that brings together the ideas of Shaivism and Yoga traditions. Gorakhnath is considered to be the founding guru of the Nath Panth. As part of the Varkari sect, Janabai was entrenched in all of this activity.

Legacy and Influence

A significant part of Janabai’s legacy survives through women’s oral tradition of Maharashtra, where women sing her songs while doing domestic chores, especially while using stone-mills. Hence, Jani is commonly associated with grinding and the stone-mill. A temple in Gopalpur, Maharashtra presents an image of Janabai grinding with her god Vitthala. There are many temples in Maharashtra dedicated to her; one temple in Gopalpur also has a room called Janabai’s samsara (world) along with temples of other three queens of Krishna/Vitthala. There are schools and colleges established by the Shri Sant Janabai Education Society, Gangakhed. Three commercial movies have been made about her life (all called Sant Janabai) in the years 1925, 1938, and 1949, along with a more recent version made in 2014 for religious purposes.

Contemporary Identifications

Janabai is usually read in context of women’s studies in Marathi and well as in the context of Marathi literature.

Networks

A sense of community with other saints is one of the central tropes of Janabai’s poetry. She lived in Namdev’s house and his family became her family, including Rajai, Gonai, Aubai (Namdev’s sister), Limbabai (Namdev’s daughter). Janabai treated herself as the fifteenth member of this group. In addition, she wrote about Jnaneshwar and referred to him as mother and friend. Jani also mentioned her other contemporaries such as Muktabai (c. 1279 – c. 1297), Chokhamela (n.d. – c. 1338), Nivrittinath (c. 1273 – c. 1297), Sopandev (c. 1277 – c. 1296), Gora Kumbar (c. 1267 – c. 1317), Kabir (c. 1398/1440 – c. 1448/1518), Visoba Khechar (n.d. – c. 1309) and others. This was her spiritual family.

Janabai is often compared with Meerbai (c. 1498 – c. 1547), a saint-poet from modern day possibly because they were both such ardent devotees of Krishna/Vitthala. However, no reference to Meera is found in Janabai’s poems.

less

Controversies

Controversy

Janabai’s relationship with Vitthala often became a cause of concern for devotees. One story tells how people gathered at Janabai’s hut to accuse her of tricking Vitthala into falling in love with her and causing him to reject the devotion shown by other devotees. She was also accused of stealing a cluster of jewels from Vitthala when he came to visit her one night. The search led to the discovery of a garland of pearls at Janabai’s house. The people decided to punish Jani for this theft by impaling her with a rod. Jani prayed to her god, and the rod became water. Seeing this miracle, people exclaimed, “blessed is Jani and her bhakti.”

Contemporary songs also tell a similar story. However, this time, the jealous party is Rukmani, Vitthala’s first wife (Poitevin and Raikar). In this version of events, Janabai is treated like the Rukmani’s younger sister, and Rukmani often throws tantrums in front of her husband Duetto the attention he gives to Janabai.

Other women within Namdev’s family also displayed jealousy towards Janabai. Janabai was often called neech, which means a lowly despicable person, not only with regard to social position but also based on actions. Janabai’s obsession and closeness with Namdev and Namdev’s affection and respect towards her could have been the cause of his mother’s and wife’s jealousy.

Feminism/Social Activism

One of the moments in which Janabai’s feminism manifests is when she addresses Vitthala as Rukmani’s husband. In several poems, she calls Vitthala, Rukmaninayaka (Rukmani’s hero), Rukmanicha kunka (Rukmani’s husband) or baap rakhumabai var (my father is Rukmani’s husband). In these descriptions, Janabai reverses the traditional form describing a woman as a man’s wife. By treating Vitthala as an extension of Rukmani, she challenges the conception of woman as man’s property.

Janabai’s unsettling of gender binaries is also connected to her rejection of caste hierarchy. In one poem, she shows awareness of her identity as a shudra woman, describing how it was taught to her by the saints that she should not regret being born a woman because god’s love does not depend on one’s gender or kul (ancestry/clan). In other poems, she praises other lower caste saints such as Chokhamela and even mentions that he was casteless.

Issues with the sources

Janabai’s signature—"says Jani” or “says Namdev’s Jani”—is considered to be the mark of her authorship. However, it is difficult to say with complete surety that all poems attributed to Janabai were composed by one person, given that the Namdev Gatha itself has multiple versions and appears to have been compiled after his death. There is also no mention of Janabai in songs composed by Namdev even though she pays homage to him and is always associated with him and his family.

less

Bibliography

Primary

Shri Sant Janabai Shikshan Sanstha. Sant Janabai: Charitra va Kavya. Gangakhed: Diamond Publications, 1976.

Mahipati. Stories of Indian Saints. Translated by Justin E. Abbott and Pandit Narhar R. Godbole. Delhi: Motilal Banarasidas Publications, 1988.

Irlekar, Suhasini. Sant Janabai. Mumbai: Maharashtra State Sahitya Ani Sanskruti Mandal, 2002.

Archival resources

Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Pune

Rajwade Mandal Museum, Dhule

Web Sources:

“Sant Janabai yanchi mahiti.” Majhi Marathi. Accessed July 9, 2021. https://www.majhimarathi.com/sant-janabai-information-in-marathi/

Mirajkar, Shyamsundar. “Janabai.” Marathi Vishwakosh. September 16, 2019. https://marathivishwakosh.org/22756/

“Sant Janabai”. Sant Sahitya. Accessed July 9, 2021. https://www.santsahitya.in/mahati-santanchi/sant-janabai/

Secondary Sources

Vanita, Ruth. "God as Sakhi: Medieval Poet Janabai and her Friend Vithabai." In Gandhi's Tiger and Sita's Smile, by Ruth Vanita, 91-104. New Delhi: Yoda Press, 2005.

Sinha, Jayita. “An Ant Swallowed the Sun”: Women Mystics in Medieval Maharashtra and Medieval England. The University of Texas, Austin, 2015. PhD Dissertation. https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/30527/SINHA-DISSERTATION-2015.pdf?sequence=1

Poitevin, Guy, and Hema Raikar. Stonemill and Bhakti. New Delhi: D.K. Printworld (P) Ltd., 1996.

Deshmukh, Madhuri. “The Mothers and Daughters of Bhakti: Janābāī in Marathi Literature.” International Journal of Hindu Studies (2020): 33-59.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully