Birth

1883, Kenwood, New York

Education

Childhood education at school in Niagara Falls, Ontario. Undergraduate and postgraduate studies at Bryn Mawr College (1901-1906). Further doctoral studies undertaken at Radcliffe College and Newnham College, University of Cambridge (1908-1913).

Death

1960, Oneida, New York

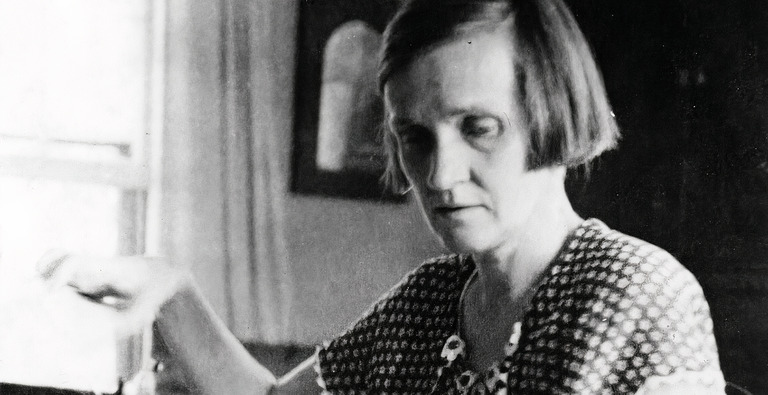

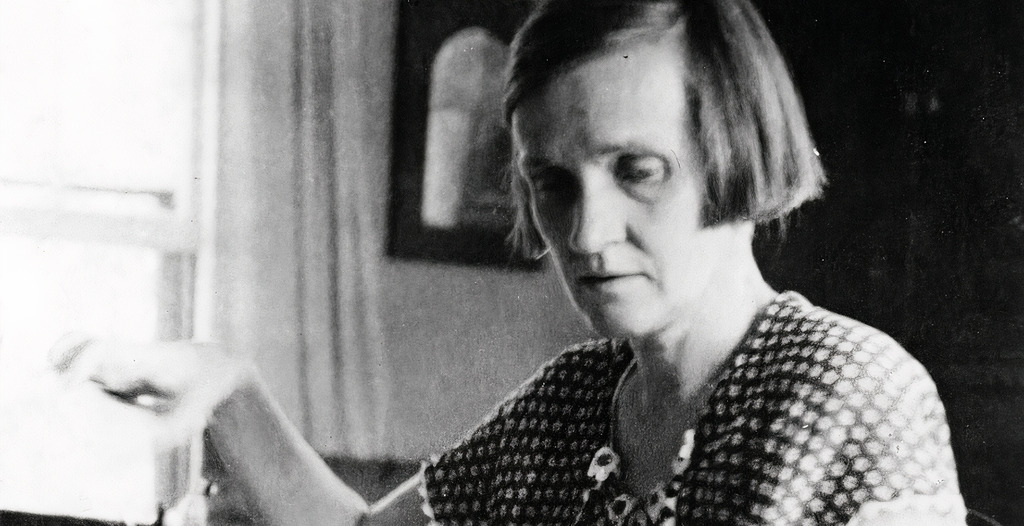

Hope Emily Allen was an academic who discovered The Book of Margery Kemp, a fifteenth-century text regarded as the first autobiography composed in English. Allen was a scholar of late-medieval English devotional culture, publishing numerous works on Richard Rolle (1300-1349), the Ancrene Riwle (also called the Ancrene Wisse), and The Pricke of Conscience.

Personal Information

Name(s) Hope Emily Allen

Date and place of birth 1883, Kenwood, New York

Date and place of death 1960, Oneida, New York

Family

Mother: Portia Marie Underhill (married surname Allen) (1842-1913)

Father: Henry Grosvenor Allen (1833-1920)

One brother, Grosvenor Noyes Allen (1874-1954)

Marriage and Family Life

Before their marriage and the birth of Hope Emily Allen, Henry Allen and Portia Underhill were members of the Oneida Community—a radical socialist Christian community in Kenwood, New York. Portia Underhill (Allen) was recognised as a spiritualist within the Oneida Community, while Henry Allen was instrumental in the business elements of the Community. Accused of “special love”—an accusation of special emotional intimacy between two members which was disallowed by the community—Henry and Portia were separated by the Oneida Community until its dissolution in 1880. After marrying in 1880, Portia gave birth to Hope in 1883. Through her mother, Allen is a cousin of famed English spiritualist and activist, Evelyn Underhill. Hope Emily Allen remained unmarried until the end of her life, with no children or known companions. She inherited familial wealth from father’s role at Oneida Silver, the Oneida Community’s successor company.

Education (longer version) Following her childhood education at school in Niagara Falls, Ontario, Allen undertook undergraduate (A.B.) and postgraduate (A.M.) studies of medieval English literature and Greek at renowned women’s college Bryn Mawr College. Allen completed her postgraduate studies in 1906, and following this, she enrolled in a PhD programme at Radcliffe College (also a women’s college) in 1908. While at Radcliffe, Allen published her first monograph, The Authorship of the Pricke of Conscience in 1910. Pursuing further studies and opportunities abroad, Allen enrolled at Newham College, University of Cambridge in 1910. Never formally completing her doctoral degree at Radcliffe, Allen remained at Newham College until 1913.

Religion

Allen’s parents were members of the socialist-perfectionist Oneida Community until 1880, when the Community formally disbanded and Henry Allen became a Canadian agent for the Community’s successor company, Oneida Silver. Allen was raised in what she called the “that most eccentric religious society,” developing an interest in and tolerance for the more “extreme” forms of Christian devotion while describing her own faith as a form of “Christian agnosticism.”

Transformation(s)

After spending more than a decade of her early adult life in higher education, attending renowned women’s colleges in both the United States and England, Allen used her familial inheritance to fund her rigorous research into late-medieval Christian devotional culture. Enjoying a life of financial independence and intellectual community, Allen utilised a vast network of feminist women scholars to cultivate an academic reputation beyond traditional universities.

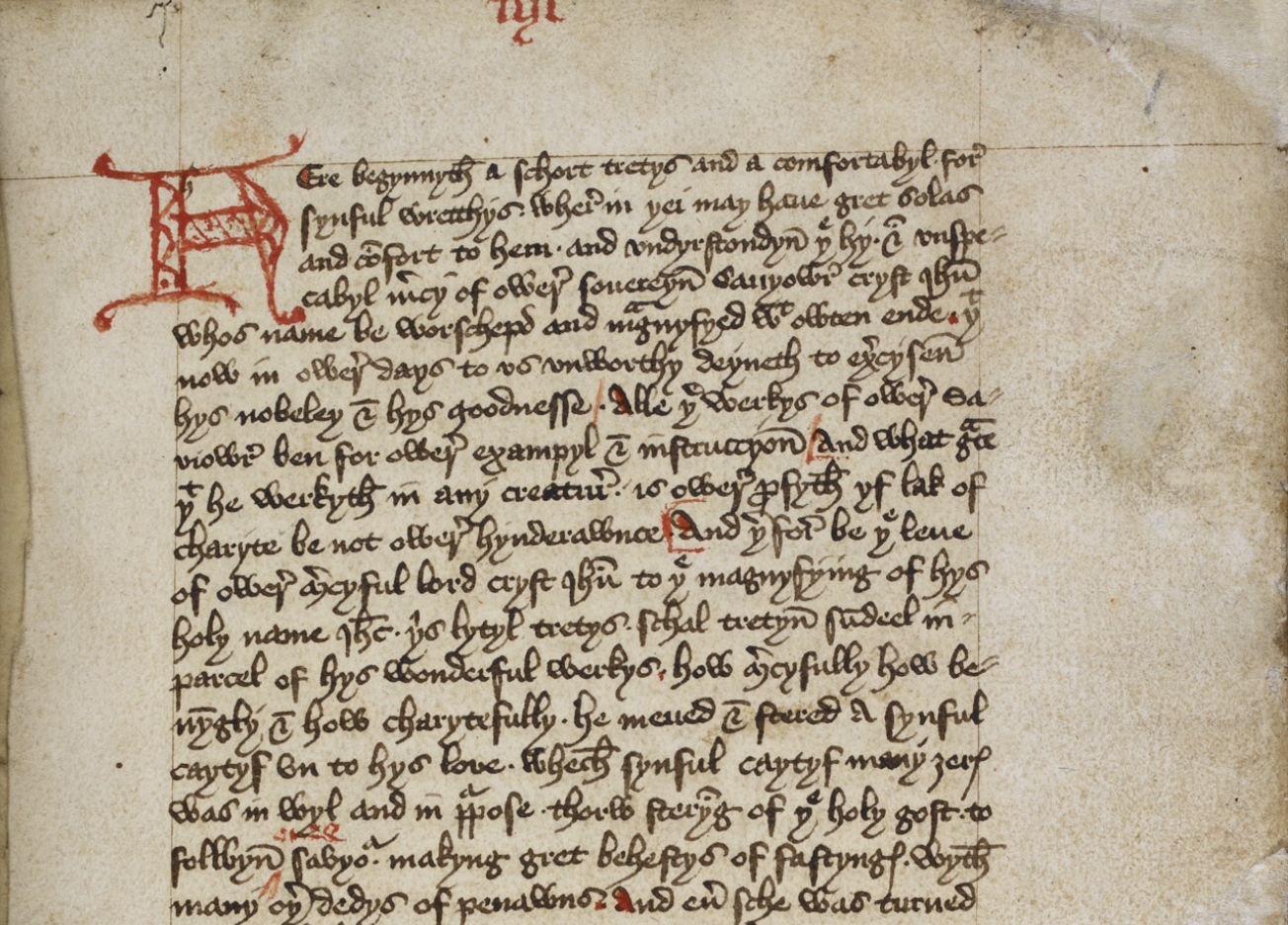

In the summer of 1934, at the behest of Evelyn Underhill, Allen was invited to the Victoria and Albert Museum to view an unidentified manuscript. There, Allen made what has become a career-defining discovery of a long-lost, perhaps sole-surviving manuscript of The Book of Margery Kempe—a fifteenth-century text regarded as the first autobiography composed in English. The Book recounts Margery Kempe’s (c. 1373-1440) spiritual transformation and visionary experiences, beginning with the traumatic birth of her first child and the following decades of her fascinating life. To date, no further manuscripts of the Book have been found. For more on Margery Kempe and her Book, see our schema on Margery Kempe, by Martha Driver.

Over the next six years, Allen worked with junior colleague and lexicographer Sanford Brown Meech to produce the first scholarly edition of The Book of Margery Kempe. Though Allen brought Meech into the project of creating the first edition of Kempe’s Book—and was also Meech’s superior—a combative relationship developed between the two, one that became notorious in the field of medieval literary studies.

Eventually, despite conflict, the first volume of the Book was published by the Early English Text Society (EETS) in 1940. This edition was filled with extensive notes by both Allen and Meech, with Allen’s notes focusing primarily on the historical context for Kempe’s experiences and writing.

Though Allen intended to author a second volume, where she would share her expert opinion on the historical context and significance of the Book, the edition was never published. Allen was an independent scholar—a common experience for upper-middle-class women in her network—and this status often prevented her from being taken seriously in her larger academic community, despite her monographs and contributions within international networks.

Most significantly, as a woman, she was disallowed from pursuing a professional career in academia and was often dismissed by male colleagues, both senior and junior. Nonetheless, her discovery of and commentary on The Book of Margery Kempe and her years of independent scholarship have made her a 20th century academic of significance.

Contemporaneous Network(s)

Female networks of both friendship and scholarship shaped Allen’s life, and are sustained by her legacy.

Allen maintained close personal and professional relationships with a network of women scholars in England, even as she was residing in New York. Allen’s network of British women scholars congregated around Cheyne Row (Walk) in Chelsea, London. These women scholars included Joan Wake and Dorothy Ellis, each of whom contributed to Allen’s decades of research in both a professional and personal manner.

Wake, Ellis, and Allen referred to themselves as the “Three Daughters of Deorman,” a reference to the Ancrene Riwle and their shared passions for medieval and early modern English history. In addition to this group of female historians, Allen’s network stretched beyond disciplinary boundaries; after the death of her father in 1920, she returned to live in London with ecologist-artist Marietta Pallis at 116 Cheyne Row. Beyond Cheyne Row and Allen’s collaborators, she also developed friendships with Mabel Day, the assistant director of the EETS from 1921 to 1949, and Sigrid Undset, a Norwegian-Danish novelist and Nobel Laureate, among others. Like Allen, many of these female collaborators and friends never married, living independently and finding community in female bonds.

Despite the difficulty Allen faced as a woman in academia, she still gained professional respect and friendship from male colleagues. While routinely avoiding formal attachment to educational institutions and enjoying her independent nature, in the 1930s Allen was briefly employed at the University of Michigan, where she worked on both the Early Modern English Dictionary and Middle English Dictionary projects. She received the praises and professional support of the project’s male leadership, despite the conflict which would later arise with Sanford Brown Meech.

After her discovery of The Book of Margery Kempe, Allen received important support from Raymond Wilson Chambers, Robin Flower, and Charles Talbut Onions— three elite figures in the British scholarly community. While battling over the edition of Kempe’s Book, Chambers, Flower, and Onions remained steadfast allies to Allen’s cause and authority on the matter, opposing Meech’s erosion of Allen’s influence on the volume.

less

Significance

Works/Agency

In addition to her discovery of the Book, Allen was an formidable scholar of late-medieval English devotional culture, publishing numerous works on Richard Rolle (1300-1349), the Ancrene Riwle (also called the Ancrene Wisse), and The Pricke of Conscience. Her works, both monographs and articles, include (but are not limited to):

The Authorship of the Pricke of Conscience (Radcliffe, 1910)

“A Note on the Lamentation of Mary” (Modern Philology, 1916)

“The Pupilla Oculi” (Modern Language Notes, 1918)

“Another Latin Manuscript of the ‘Ancrene Riwle’” (MLR, 1922)

“Some Fourteenth-Century Borrowing from ‘Ancrene Riwle’” (MLR, 1923)

Writings Ascribed to Richard Rolle, Hermit of Hampole, and Materials of His Biography (1927)

English Writings of Richard Rolle, Hermit of Hampole (1931)

“The Localisation of Bodl. MS. 34.” (MLR, 1933)

The “Ancrene Riwle” and Geoffrey of Monmouth (MLR, 1934)

In 1927, Allen was awarded the Rosy Mary Crawshay Prize by the British Academy for her monograph Writings Ascribed to Richard Rolle, Hermit of Hampole, and Materials of His Biography (1927).

Reputation

During her life, Allen gained a reputation as a rigorous and formidable scholar. This is exemplified in Father Herbert Thurston’s description of her Writings Ascribed to Richard Rolle (1927): “We are tempted to think that she has perhaps been even too meticulous, too conscientious, in her hunting down of every recorded text and every reference which could afford a clue to the elucidation of the rather obscure problems of Richard Rolle's literary activities. The standard she sets would seem to demand too large a proportion of man's limited working days to be practicable for any but a very few.” Allen’s ability to operate as an independent scholar—both a luxury and a consequence of her marginalization as a woman—allowed her to undertake strenuous, meticulous, and evidently unending study of her subjects. This reputation is maintained in posthumous commentary; Eminent Kempe-scholar Carolyn Dinshaw notes of Allen’s contribution to the 1940 edition of the Book: “[S]he worked on her notes until the very last minute before publication, extending the present moment until she could no longer, until her dilations had to give way to the press’s punctuality.”

Legacy and Influence

With the growth of the field of Kempe Studies over the past four decades, Allen’s reputation grows as well. She is a well-known figure in medieval literary and cultural studies, due to contributions and studies of texts which are foundational to our knowledge of late-medieval devotional culture.

Furthermore, her discovery of the Book and her conflict with Meech have become a key source of her fame. Archival resources from Allen’s personal papers are currently held at Bryn Mawr College. Further collections are also held at the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, and the Northamptonshire Record Office.

less

Controversies

The greatest controversy which marked Allen’s professional life was her embattled relationship with Sanford Brown Meech. As noted briefly above (see “Transformations”), Meech is recognised today as an oppressive force against Allen. The result of this conflict was the minimisation of Allen’s contributions to the first edition of the Book and the misrepresentation of Meech as the work’s chief editor. Such combative behavior was characteristic of Meech at the time, against male and female colleagues alike.

less

Clusters & Search Terms

Current Identification(s)

Medieval English Literature

Medieval English History

Medieval Devotional Culture

Christian Mysticism

Search Terms

Margery Kempe

15th Century

Fifteenth Century

Late Medieval

Mysticism

Mystics

Christianity

Historian

less

Bibliography

Primary (selected):

Allen, Hope Emily. “A Note on the ‘Lamentation of Mary’.” Modern Philology Notes 14, no. 4 (1916): 255-256.

———. “Another Latin Manuscript of the ‘Ancrene Riwle’.” The Modern Language Review 17, no. 4 (1922): 403.

———. English Writings of Richard Rolle, Hermit of Hampole (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1931).

———. “Some Fourteenth-Century Borrowing from ‘Ancrene Riwle’.” The Modern Language Review 18, no. 1 (1923): 1-18.

———. “The “Ancrene Riwle and Geoffrey of Monmouth” The Modern Language Review (1934): ___-___.

———. The Authorship of the Pricke of Conscience (Boston: Ginn, 1910)

———. “The Localisation of Bodl. MS. 34.” The Modern Language Review 28, no. 4 (1933): 485-487.

———. “The Pupilla Oculi.” Modern Language Notes 33, no. 3 (1918): 186.

———. “The Three Daughters of Deorman.” PMLA 50, no. 3 (1935): 899-902.

———. Writings Ascribed to Richard Rolle, Hermit of Hampole, and Materials of His Biography (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1927).

Meech, Sanford Brown, and Hope Emily Allen, eds. The Book of Margery Kempe, vol. 1 (London: Early English Text Society, 1940).

Archival Resources (selected):

Hope Emily Allen Papers, Special Collections Department, Bryn Mawr College Library

Hope Emily Allen Papers. MSS. English Letters c. 212, d. 217, and MS. Engl. Misc. c. 484. Bodleian Library, Oxford.

Web Resources (selected):

“WaltsMusings: The Oneida Community.” https://waltsmusings.wordpress.com.

Articles and Chapters (selected):

Atkinson, Clarissa W. “In Memoriam: Hope Emily Allen (1883-1960).” 14th Century English Mystics Newsletter 9, no. 4 (1983): 210-217.

Ciklamini, Marlene. “Sigrid Undset’s Letter’s to Hope Emily Allen.” The Journal of the Rutgers University Libraries 33, no. 1 (1969): 20-27.

Dinshaw, Carolyn, “In the Now: Margery Kempe, Hope Emily Allen, and Me,” in How Soon is Now?: Medieval Texts, Amateur Readers, and the Queerness of Time (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012), 105-127.

Hirsh, John C. “Hope Emily Allen, the Second Volume of The Book of Margery Kempe, and an Adversary.” Medieval Feminist Forum 31 (2001): 11-17.

Mitchell, Marea. “‘The Ever-growing Army of Serious Girls Students’: The Legacy of Hope Emily Allen.” Medieval Feminist Forum 31 (2001): 17-29.

Williams, Deanne. “Hope Emily Allen Speaks with the Dead.” Leeds Studies in English 35 (2004): 137-160.

Books:

Hirsh, John C. Hope Emily Allen: Medieval Scholarship and Feminism (Norman, OK: Pilgrim Books, 1988).

Comment

Your message was sent successfully