Birth

June 17th, 1759 in London, UKEducation

Home SchooledDeath

December 15th, 1827 in Paris, FranceReligion

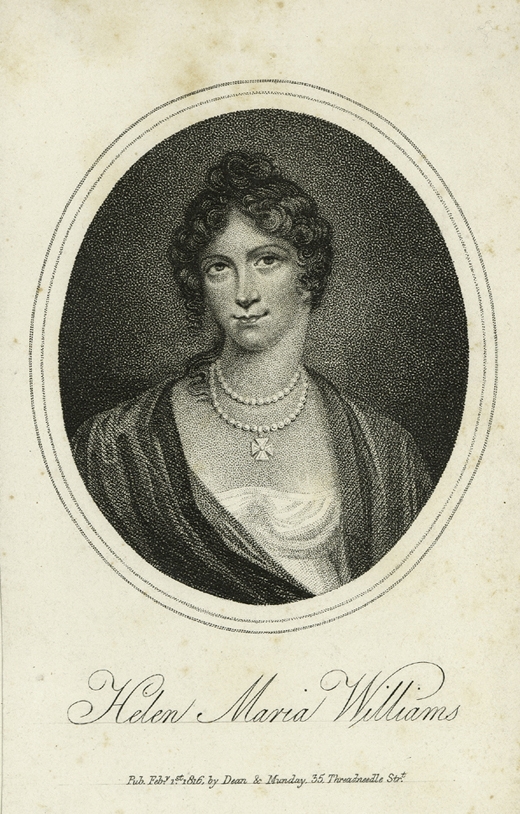

PresbyterianHelen Maria Williams was a poet, novelist, translator, and essayist known for her writings on the French Revolution and her support of radical causes.

Personal Information

Name(s)

Helen Maria Williams

Date and place of birth

Born 17 June 1759 in London

Death and place of death

Natural death, 15 December 1827 at Rue Neuve St Eustache, Paris

Family

Mother: Helen Hay (1730-1812), later Williams.

Father: Charles Williams. Died in 1762. Charles’ state and pension became the main source of income for the family after his death. He served as the Secretary for the Island of Minorca and, after 1743, served the army in Cork, Ireland. He was a widower when he married Helen on the 1st of June 1758.

Marriage and Family Life

Williams’ half-sister was named Persis (1743-1823) born of Charles’ first marriage). Persis was named after her mother. Also born of Charles and Helen’s marriage was Cecilia Williams (?-1798), later Coquerel.

Williams traveled to France both in 1790 and 1791 with her mother, Cecilia and probably Persis. In 1792, they all settled permanently in France.

Cecilia married Marie-Martin-Athanase Coquerel and they had two children, Athanase Jr. and Charles. Helen Maria raised her nephews after Cecilia’s death in 1798.

Williams never married but she had a relationship with John Hutford Stone (1763-1818), a British businessman settled in Paris. The relationship lasted from 1792 to 1818.

Education

Williams and her sisters were educated by their mother following the principles of English dissent. For that matter, the reading of the bible was fundamental for Williams and her sisters. After the family moved to London in 1781, she became a member of the Presbyterian congregation in Westminster. Its minister, Andrew Kippis, became her mentor, introduced her to the literary circles in London and encouraged her to publish her writings.

Religion

Presbyterian - English dissenter.

Transformation(s)

The first transformation happened in her early twenties, when she moved to London and started her career as an author by publishing poems of sensibility, which were very well-received by her contemporaries. Her first poem was signed ‘by a lady’, but after her third publication, Peru (1784), she started publishing in her own name.

The event that had the greatest impact in Williams’ life was the outbreak of the French Revolution. Before her major work, Letters Written in France (1790), she had already shown in her poems her interest in politics by supporting the American Revolution and the Anti-Slavery Campaigns. From the publication of Letters onwards, Williams would set poetry aside (with the exception of Poems on Various Subjects, published in 1823, in which she revisits her early poems) and dedicated her career to analysing the political and historical events she was witnessing in France. She became a political author in a time in which politics was not considered a suitable subject matter for a woman. As a result, she became the object of continuous attacks that resulted in the loss of the good reputation she had earned in her twenties.

Contemporaneous Network(s)

In England, Elizabeth Montagu and the Bluestocking circle circulated manuscripts of her poems. Williams dedicated her poem Peru (1784) to Montagu. She corresponded with Anna Seward, Hester Thrale Piozzi and Penelope Pennington. Both Seward and Piozzi ended their friendship with Williams on account of her support of the French Revolution. Joana Baille, Dr. John Moore and Mr. Cadell visited her literary salon in London.

Throughout her works, Williams shows her support for the Girondins. Manon Roland, Brissot, Abbé Gregoire, Vergniaud or Saint-Étienne visited her literary salon in Paris. She also befriended literary stars such as Bernardin de Saint Pierre, military leaders such as Alexander Pétion, Thaddeus Kosciousko and Francisco de Miranda, explorer Alexander von Humboldt and diplomat Joel Barlow. Mary Wollstonecraft and Sydney Owenson visited her during their respective stays in Paris.

less

Significance

Works/Agency

Helen Maria Williams is known for her writings on the French Revolution. During the first decade of her career, she produced poems that anticipate her political views as they deal with pacifism (as in Edwin and Eltruda and An Ode on the Peace), the anti-slavery movement (as in A Poem on the Bill Lately Passed for Regulating Slave Trade) and a critical view of colonialism (as in Peru). In 1786, she published a collection of poetry entitled Poems, that she would revisit in 1823 as Poems on Various Subjects. In 1790, she published her first and only novel, Julia, inspired by Rousseau’s La Nouvelle Héloïse. The latter includes a poem on the Bastille that shows Williams’ new-born interest in the French Revolution.

After her first trip to Paris in 1790, Williams wrote eight volumes of her series Letters from France (1790 -1796), a first-hand chronicle of the political events she witnessed in France. In 1798, she published a travelogue entitled A Tour in Switzerland. In 1801, she wrote a new chronicle on the Revolution, Sketches of the State of Manners and Opinions in the French Republic. She also worked on the translation of the corresponde of the late king of France, The Political and Confidential Correspondence of Lewis the Sixteenth (1803) in which she includes her own commentary after each letter. In 1815 and 1817, after the end of the Napoleonic era, she published her accounts of that period entitled Narrative of the Events and Letters on the Events, respectively. Her last work was her memoir Souvenirs de la Révolution Française (1827), in which she revisits her experiences of a life-long commitment to the revolutionary cause.

Williams also worked as a translator of French works into English, the most-well known ones being Paul and Virginia (1795) by Bernardin de Saint Pierre and Researches (1824) and Personal Narrative (1814-1827) by Von Humboldt.

Reputation

Williams’ early poetry granted her a good reputation in England as a writer of Sensibility. Her first volume of Letters was also well-received. As the Revolution advanced and it became more violent, British public opinion increasingly turned against it. As a result, Williams started to be portrayed in anti-revolutionary publications as a staunch Jacobin. She was also criticized in the press for her relationship with John Stone, as they did not marry. As a result, she lost her former reputation. The decline of her popularity is evident in the obituaries dedicated to her. For instance, the Monthly Review states that her works “have been already forgotten” and the Gentleman’s Magazine describes her as “pre-eminent among the violent female devotees of the French Revolution”.

In posterity, she was excluded from the canon of the British responses to the French Revolution. For the most part of the 20th Century, her chronicles were considered to be inaccurate and unreliable. Thus, her work did not attract the attention of the scholarship until the late 70s, when Feminist scholars started to recover forgotten works by women and the Romantic canon was put into question.

Legacy and Influence

Regardless of her decline in popularity, the works by Helen Maria Williams continued to be read in the first half of the nineteenth century. For instance, a translation of Williams’ The Political and Confidential Correspondence of Louis XVI was found among Mary Shelley’s papers. William Hazlitt used Letters from France for his Life of Napoleon Bonaparte and reprinted some excerpts as appendixes to his work. In a way, even though her name was forgotten, her words were passed on to posterity through the works of later authors.

The recovery of Williams’ work by Femenist scholarship in the late 20th Century initially put the emphasis on her facet as a poet and novelist -even though these genres only constitute a small part of her work. In the 1990s, the interest in her chronicles of the French Revolution became more prominent. Even though she had been left out in the studies about the controversy surrounding the French Revolution in Britain, this is changing in recent years. Her contribution to the political debates of her time have been recognized by the scholarship. Nevertheless, the influence of her works in France is still unexplored for the most part.

less

Controversies

Controversy

As mentioned above, Williams lost her reputation and even some of her friends for being a supporter of the French Revolution in a time in which France was at war with her native country. Besides, the press in Britain misinterpreted her political position and portrayed her as a Jacobin -even though she always supported the Gironde-. Later on, the British press accused her of having changed sides and of having become a royalist. Williams maintained that, even though she rejoiced at Napoleon’s fall because she considered him a tyrant, she had never betrayed her political ideals.

The press also attacked Williams for being a woman writer who focused on politics. For instance, regarding her chronicles she wrote on The Terror, the Gentleman’s Magazine writes the following: “Miss Williams must excuse us if we say she has debased her sex, her heart, her feelings, her talents, in recording such a tissue of horror and villany”.

New and unfolding information and/or interpretations

Williams’ participation in the political debates of her time is being reconsidered. Williams’ Letters took part in the defence of the French Revolution in Britain together with Macaulays’ Observations on the Reflections of the Right. Hon Edmund Burke (1790), Paine’s Rights of Man (1791) or Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Men, rather than being a mere account of her travels in Paris. As a result, she is not regarded as a marginal figure anymore but as an authoritative source on the French Revolution.

less

Bibliography

Primary (selected):

“Literary and Miscellaneous Intelligence. Foreign and Domestic”. The Monthly Review (London: Hurst, Chance and Co., January-April 1828): 139.

“Obituary.-Helen Maria Williams”. The Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Chronicle, vol.I (London: J.B. Nicholson and Son, January-June 1828): 373.

“Scenes which have passed in Prisons of Paris. By Helen Maria Williams”. The Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Chronicle, vol. 65, part 2 (London: John Nichols, 1795): 1030

Williams, Helen Maria. A Poem on the Bill Lately Passed for Regulating Slave Trade. London: T. Cadell, 1788.

--. A Tour in Switzerland; or, A View of the Present State of the Governments and Manners of those Cantos: with Comparative Sketches of the Present State of Paris. London: G.G. and J. Robinson, 1798.

--. An Ode on the Peace. By the Author of Edwin and Eltruda. London: T. Cadell, 1783.

--. Edwin and Eltruda. A Legendary Tale. London: T. Cadell, 1782.

--. Julia, A Novel Interspersed with Some Poetical Pieces. London: T. Cadell, 1790.

--. Letters from France: Containing a Great Variety of Interesting and Original Information Concerning the Most Important Events that Have Lately Occurred in that Country (London: G.G. and J.Robinson, 1793)

--. Letters on the Events which Have Passed in France since the Restoration in 1815. London: Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, 1819.

--. Letters Written in France in the Summer 1790, to a Friend in England. London: T.Cadell, 1790.

--. Narrative of the Events Which Have Taken Place in France, from the Landing of Napoleon Bonaparte, on the 1st of March, 1815, Till the Restoration of Louis XVII. London: John Murray, 1815.

--. (trans.). Paul and Virginia. By Bernardin Saint-Pierre. London: G.G. and and J. Robinson, 1795.

--. (trans.) Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent, During the Years 1799-1804. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1814.

--. Poems, in Two Volumes. London: Thomas Cadell, 1786.

--. Poems on Various Subjects with Introductory Remarks on the Present State of Science and Literature in France. London: G. and W. B. Whittaker, 1823.

--. Souvenirs de la Révolution Française. Paris: Dondey-Dupré, 1827.

--. Sketches of the State of Manners and Opinions in the French Republic, Towards the Close of the Eighteenth Century in a Series of Letters. London: G.G. and and J. Robinson, 1801.

--. The Political and Confidential Correspondence of Louis the Sixteenth; with Observations on Each Letter. London: G. and J. Robinson, 1803.

Archival resources (selected):

Blakemore, Steven. Crisis in Representation: Thomas Paine, Mary Wollstonecraft, Helen Maria Williams, and the Rewriting of the French Revolution. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press; London; Cranbury, NJ: Associated University Presses, 1997.

--.“Revolution and the French Disease: Laetitia Matilda Hawkins's Letters to Helen Maria Williams”. Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, 36. 3, Summer 1996: 673-691.

Crook, Nora. Mary Shelley's Literary Lives and Other Writings, volume 4. Routledge: London and New York, 2003.

Duckling, Louise . “From Liberty to Lechery: Performance, Reputation and the “Marvelous History” of Helen Maria Williams”. Women’s Writing, 17, 2010: 74-92.

Favret, Mary A. Romantic Correspondence: Women, Politics, and the Fiction of Letters. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Fraistat, Neil, Lanser, Susan S. “Introduction”. In Neil Fraistat & Susan S. Lanser (eds.), Letters Written in France by Helen Maria Williams. Peterborough: Broadview Press, 2001.

Franklin, Caroline. “The colour of a riband”: Patriotism, history and the role of women in Helen Maria Williams's Sketches of Manners and Opinions in the French Republic (1801)”. Women’s Writing, 13, 2006: 495-508.

Jones, Chris. “Travelling Hopefully: Helen Maria Williams and the Feminine Discourse of Sensibility”. In Amanda Gilroy (ed.), Romantic Geographies. Discourses of Travel 1775-1844. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000. 93-108.

Jones, Vivien. “Women Writing Revolution: Narratives of History and Sexuality in Wollstonecraft and Williams”. In Stephen Copley and John Wale (eds.), Beyond Romanticism: New Approaches to Texts and Contexts, 1780-1832. London: Routledge, 1992. 178-199.

Kean, Angela. Revolutionary Women Writers. Charlotte Smith & Helen Maria Williams. Devon: Northcote House Publishers, 2013.

Kelly, Gary. Women, Writing and Revolution 1790-1827. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993.

Kennedy, Deborah. Helen Maria Williams and the Age of Revolution. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 2002.

Leblanc, Jacqueline. “Politics and Commercial Sensibility in Helen Maria Williams’ Letters from France”. Eighteenth-Century Life, 21, 1, 1997: 26-44.

Ledden, Mark. “Perishable Goods: Feminine Virtue, Selfhood and History in The Early Writings of Helen Maria Williams.” Michigan Feminist Studies, 9, 1994-5: 37-65.

Ty, Eleanor. Unsex’d Revolutionaries: Five Women Novelists of the 1790s. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993.

Web resources (selected):

Kennedy, Deborah F."Williams, Helen Maria (1759–1827), writer." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23. Oxford University Press. Date of access 29 Nov. 2021, <https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-29509>

Comment

Your message was sent successfully