Birth

Moon Court, Boston, Massachusetts

Education

Trained by Parents, Home Schooled , Variable , UnknownDeath

July 11th, 1829 in Dorchester, Boston, MA, USAReligion

Trinitarian Congregationalist, UniversalismHannah Mather Crocker was an American women's rights advocate and writer. Throughout her lifetime, she wrote poems, sermons, tracts, and monographs. Her writings promoted women’s intellectual equality with men.

Personal Information

Name(s)

Hannah Mather; Hannah Mather Crocker; H.M. Crocker, also wrote under pseudonyms including Prudencia; Increase Mather Jr. of the Inner Temple; a lady; a Boston lady; a Lady Masonic, the Mistress of St Ann Lodge; Justicia; and Original Antiquarian

Date and place of birth

27 June 1752, Moon Court, Boston, Massachusetts

Date and place of death

11 July 1829, Dorchester, Massachusetts

Family

Mother: Hannah Hutchinson (1714-1781), daughter of Sarah Foster and Thomas Hutchinson, Sr.; her brother, Thomas Hutchinson, Jr, governed Massachusetts Bay prior to the American Revolution. The Hutchinsons were a wealthy, Massachusetts family descended from Anne Hutchinson, a noted spiritual advisor and religious reformer driven out of the early Massachusetts Bay Colony. Most of Hannah Mather Crocker’s wealth derived from her maternal line. Hannah Hutchinson married Samuel Mather on 23 August 1733.

Father: Samuel Mather (1706-1785), son of Elizabeth Clark and Cotton Mather. Graduated from Harvard and served as the fourth minister at the Second Church of Boston, starting in 1732, later moving to found the North Bennet Street Church. He descended from what his daughter Hannah later called “the four-fold line of Mathers,” i.e. four generations of Massachusetts Mather ministers: Richard, Increase, Cotton, and Samuel.

Marriage and Family Life

Crocker was the youngest of seven children. Two of her brothers died while she was relatively young, one from a fever picked up while serving as a surgeon for a colonial regiment stationed in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and the other at sea. Her remaining brother was estranged from the family for most of his life for Loyalist sympathies during the Revolution; he lived in London as an American refugee, but returned to Boston and reconciled with Hannah shortly before his death.

The sisters were relatively close, and likely studied together with their parents. Crocker included a poem by the sister closest to her in age, Abigail also called Nabby, in her volume of Reminiscences; on the topic of “Friendship,” Nabby had dedicated the poem to Crocker.

Fairly little is known about Crocker’s early life, but in her later years she recorded anecdotes which suggest a woman of character and action. In one tale recounted in her manuscript history of Boston, she remembered smuggling letters out of British-occupied Boston during the American Revolution. The letters were concealed under her dress, which she defiantly dared a British soldier to search. He declined and she successfully delivered the letters from her father to a leader of the American forces.

On 18 March 1779 she married Joseph Crocker, a Harvard graduate, and a captain in the Revolutionary War. Their relationship may well have been unusually equitable for the era. One of Crocker's writings, the “North Square Creed,” affirmed the importance of women's voice and self-determination in marriage. Three copies of the Creed survive, one bearing a number of initials including JC. Their marriage produced ten children before he died in 1797.

Although Joseph Crocker left Hannah Mather Crocker relatively little money, she had inherited several pieces of property from her parents that she actively managed, albeit with her husband’s brother serving as trustee. Surviving documents attest to her management and sale of land, houses, and two family tombs including the bones in the Hutchinson family tomb.

Education

Crocker likely received the majority of her schooling at the hands of her parents. No records of her having attended a school or academy had been uncovered. Her writings attest to her education and fluency in religion, languages, literature, history, and politics. Her study of languages likely included Latin, Greek, and Hebrew given references to reading Bibilical texts in the original. Regardless of whether her education took place inside or outside her home, she had access to one of the largest libraries in Boston in the portion of the Mather family library which was held by her father, Samuel Mather. Crocker also participated in freemasonry and was familiar with the principles, history, symbolism, and language of Masonry.

Religion

Crocker was raised in the established church of Massachusetts Bay. She remained a Trinitarian Congregationalist to the end, albeit sympathetic to a liberal faction advocating for Universalism.

Contemporaneous Network(s)

Little documentation survives with respect to Crocker’s involvement in female networks. Around the time of her marriage, she established a women-only Masonic-equivalent lodge along with other Boston matrons. In conjunction with this, she authored the “North Square Creed” which affirmed the importance of women’s voices and self-determination within marriage. Several copies survive, but bearing only initials thus rendering it nearly impossible to ascertain her colleagues in that enterprise. Relatively few of her letters survive, and none are addressed to other Massachusetts female intellectuals (Mary Warren, Judith Sargent Murray), although Crocker dedicated a poem to fellow Boston historian Hannah Adams.

On the other hand, there is ample documentation that Crocker had regular interactions with several leading male historians and antiquarians. These included Massachusetts Historical Society members James Savage, Abiel Holmes, and Joseph McKean; area collectors and antiquarians Ephraim Eliot, William Bentley, and William Jenks; and American Antiquarian Society founder Isaiah Thomas.

Crocker’s engagement with male historical and antiquarian circles drew in part upon control of her father’s library. Her husband was not involved in these, nor was his brother who served as trustee and supported Crocker after her husband’s death. She arguably used control over access to portions of her father’s library and manuscript materials documenting successive generations of Boston-area Mather ministers as a means to access and interact with historians and antiquarians; Bentley once visited Crocker and later left with a few items of Matheriana, recording the visit in his diary.

Crocker’s interactions with Thomas are worthy of particular note. The two corresponded and negotiated the partial sale and partial donation of the remainder of her father’s library to the American Antiquarian Society; she had previously deposited part of the library with the Massachusetts Historical Society. Subsequent interactions include Thomas’ likely subscription to her treatise on female intellectual equality, and his later consultation with her as to the veracity of the early eighteenth-century travel journal of Sarah Kemble Knight.

Further, Crocker’s three longer publications appeared in print following her negotiations with Thomas to sell part of her father’s library. Publication at the time required either authors to front money for all aspects of printing (paper, ink, composition) or find subscribers willing to support printing. Crocker’s first two treatises contain no evidence of being published by subscription, and she may have paid for their printing from the proceeds of selling part of the library. Her initial publications in turn may have contributed to her third work appearing by subscription.

less

Significance

Works/Agency

Crocker composed a variety of materials over her lifetime, including poems, sermons, tracts, and monographs. Several poems appeared in print before and during her marriage, but most surviving works date from after her husband’s death when her children were grown. Indeed, her known publications document a representative tale of an articulate, literary figure whose obtained sufficient time to write and produce when freed from maternal duties.

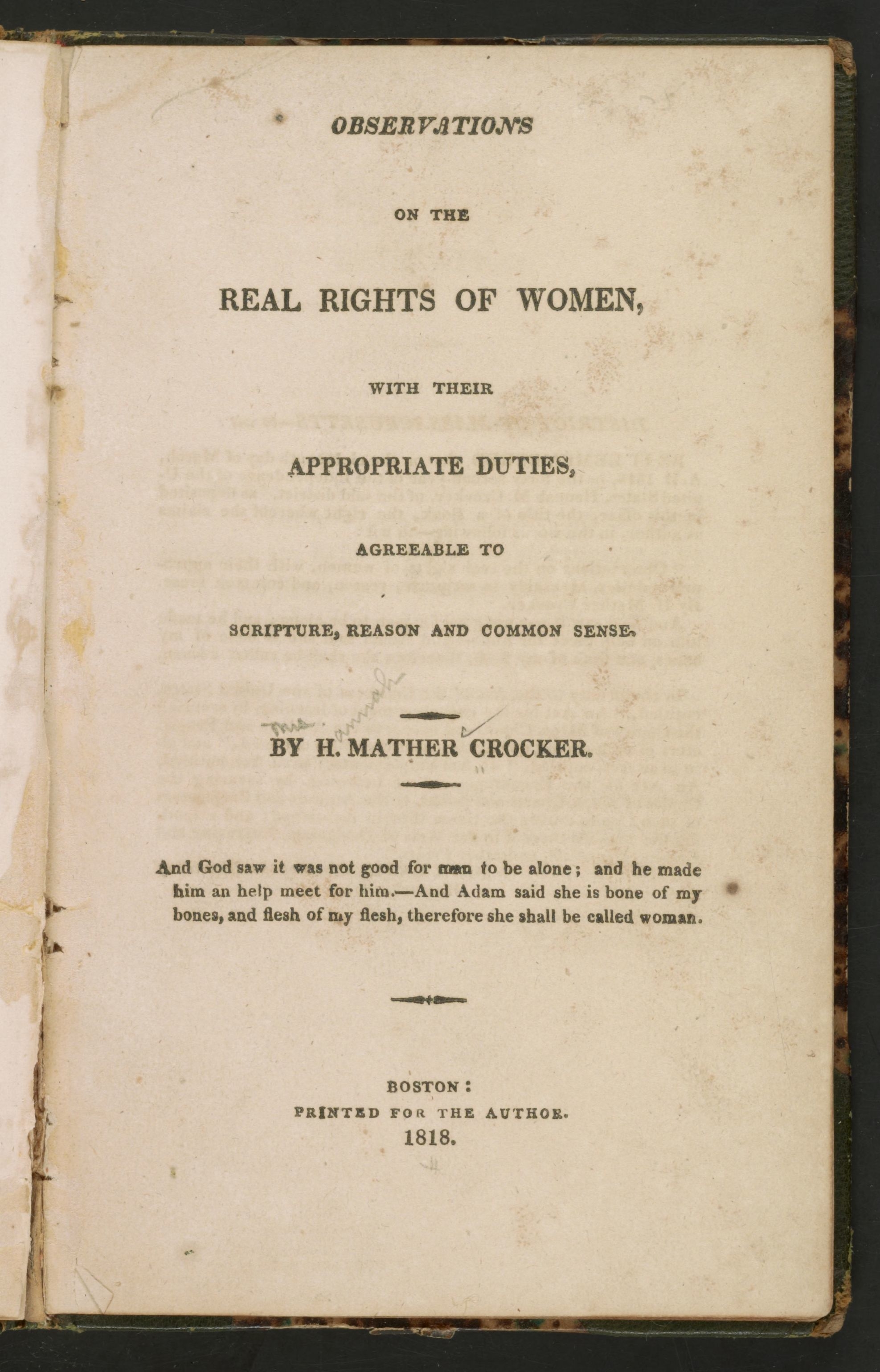

Crocker published three longer works, in her last decades (two tracts on freemasonry and temperance and a monograph on women’s intellectual equality with men), and worked on a fourth longer work (on the history of Boston) which was not published until the early twenty-first century. Many of her manuscript works likely circulated through local literary or historical circles, but their readership is unknown. She was also involved in founding a charity school for girls, one of the first of its kind in Boston.

Her published works, along with many of her unpublished writings, advocate for women’s intellectual equality with men even when putatively focused on other topics (freemasonry, temperance). Her other writing interests included antiquarianism, history, and religious and political matters. Several of her surviving manuscripts address theological considerations with respect to Biblical accounts and contemporary disputes.

She wrote at a time when many authors, male and female, used pseudonyms on their print and manuscript works. Several of Crocker’s pseudonyms included claims to precedence and importance. Most notably, the use of “Increase Mather, Jun. of the Inner Temple” on manuscript sermons presented her not merely as a lineal descendant of the Mather line but a nearly full heir to the generations of Mather ministers preceding her (father Samuel, grandfather Cotton, great-grandfather Increase, and great-great grandfather Richard). Other pseudonyms followed common naming practices: general descriptors (Boston lady, Lady Masonic) and embodied ideals (Prudencia, Justicia).

Reputation

During her lifetime, Crocker achieved a modest reputation as a woman of letters and antiquarian and historical matters within greater Boston circles. She corresponded with several influential antiquarians, historians, and collectors of the time. For some her appeal lay in control over access to the books and manuscripts of her male forbears, and at least one pooh-poohed one of her historical accounts of a smuggling tunnel in the North End, that later historians have vindicated. Other historians and antiquarians consulted her on diverse historical matters.

For many years following Crocker’s death, she was remembered primarily in conjunction with American Antiquarian Society’s holdings of Mather Family Papers. Crocker donated most of the papers at the same time as she donated part of her family library; Thomas purchased and donated another portion. The majority of the papers documented her paternal ancestors, but the gift included some of her manuscript writings. She donated a few additional manuscripts several years later. The New England Historic Genealogical Society acquired her manuscript history of Boston, Reminiscences, later in the nineteenth century.

Nevertheless, her name was largely forgotten. Rediscovery and scholarship on Crocker took place in several distinct waves. A few instances of recognition in the late twentieth century as part of the rise of women’s history and women’s and gender studies. The bulk of scholarship on her dates to the twenty-first century, as literary scholars, historians, and political scientists. All four of Crocker’s major works were republished in 2011: the three printed works plus an excerpt from Reminiscences, in a scholarly edition edited by Constance J. Post and the full text of Reminiscences in a scholarly edition edited by Eileen Hunt Botting and Sarah L. Houser. A number of her essays, sermons, and poems also survive, some in manuscript form only while others were included in Post and/or Botting and Houser's editions of her writing.

less

Controversies

Controversy

The early nineteenth-century included a hostile backlash against Mary Wollstonecraft and like-minded advocates of women’s rights, along with a general diminishment of women’s rights in post-Revolutionary America. Within this climate, Crocker expressed her beliefs carefully, balancing her own preferences in relation to then-current ideals of appropriate womanhood. Her writings have long been overshadowed by those of others. Recent scholarship, has begun to situate Crocker within discussion of the history of women’s rights advocacy and re-frame her as an early feminist and important literary and historical figure.

less

Bibliography

Primary (selected):

Crocker, Hannah Mather, as “A Lady of Boston.” A Series of Letters on Freemasonry by a Lady of Boston. Boston: John Eliot, 1815; reprinted in Hannah Mather Crocker. Observations on the Real Rights of Women and Other Writings, edited by Constance J. Post, 39-60. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011.

Crocker, Hannah Mather, as “H. Mather Crocker.” Observations on the Real Rights of Women. Boston: John Eliot, 1818; reprinted in Hannah Mather Crocker. Observations on the Real Rights of Women and Other Writings, edited by Constance J. Post, 71-144. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011.

Crocker, Hannah Mather, as “H.M. Crocker,” School of Reform, or Seaman’s Safe Pilot to the Cape of Good Hope. Boston: John Eliot, 1816; reprinted in Hannah Mather Crocker. Observations on the Real Rights of Women and Other Writings, edited by Constance J. Post, 61-70. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011.

Crocker, Hannah Mather. Reminiscences and Traditions of Boston, edited by Eileen Hunt Botting and Sarah L. Houser. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2011.

Archival resources (selected):

American Antiquarian Society

http://americanantiquarian.org/

American Antiquarian Society Archives

http://americanantiquarian.org/archivessd.htm

Mather Family Papers

http://www.americanantiquarian.org/Findingaids/mather_family.pdf

New England Historic Genealogical Society

http://www.americanancestors.org/home.html

Crocker, Hannah Mather, Reminiscences and Traditions of Boston. Mss.

Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division

Crocker, Hannah Mather. Observations on the Real Rights of Women and Other Writings

Web resources (selected):

For a more complete listing of Crocker’s known publications and surviving archival writings, click here.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully