Birth

June 11th, 1884 in İstanbul, TurkeyEducation

American College for Girls 1893-1901.

Death

January 9th, 1964 in İstanbul, TurkeyReligion

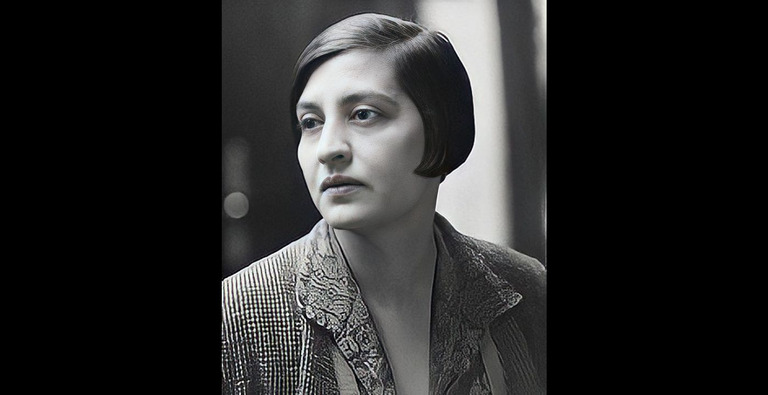

MuslimHalide Edip Adıvar was a Turkish novelist and feminist who was politically active in the anti-colonialist nationalist struggle in Anatolia. Edip wrote more than twenty-five novels and has had a deep impact on Turkish literature. In her novels and memoirs, Edip conveys one of the most detailed descriptions of daily life and the development of events between the occupation of Izmir in 1919 and the Turkish victory in the War of Independence of 1922. Her autobiographical novel, A Shirt of Fire, is her most famous work.

Personal Information

Name(s) Halide Edip (later Adıvar)

Date and place of birth

11 June 1884 Istanbul

Date and place of death

9 January 1964 Istanbul (kidney failure)

Family

Edip grew up with her maternal grandmother Nakiye Hanum, a very important figure in her memoirs.

Mother: Edip's mother Bedrifem Hanum was a member of the Nizami family, known for their connection to a religious sect in Islam called Mevleviyya, which is a school of Sufism founded by Rumi.

Father: Her father Mehmet Edip Bey was a Jewish convert of Salonikan origin.

Marriage and Family Life

Salih Zeki, who is a mathematics teacher, was Edip’s first husband (1901-1910) and father of her two sons: Ayetullah (born in 1903) ve Hasan Hikmetullah Togo (born in 1905).

Ayetullah and Hikmetullah appear either as sources of joy in routine circumstances or of worry in times of turmoil in her memoirs Mor Salkımlı Ev.

Her husband bridged her concerns with politics and her family by introducing Edip to the well-known revolutionaries and writers of her time. Yet he diverted Edip from her writing, as she concerned herself more with helping her husband in his writing rather than practicing her own, but became a well-known public speaker and a revolutionary after their divorce. Edip had divorced Zeki after he took on a second wife, when polygamy was a legal practice but widely unpracticed in Istanbul. Edip's ideals as a feminist could not let her tolerate polygamy. Thus, she divorced him, without ever forgetting how she was offended.

Dr. Adnan (later Adıvar) is Edip’s second husband. They were married in 1917 remained married till his death in 1955.

The surname ‘Adıvar’ was given to the couple following the surname law in 1934 by president and founder of the republic Atatürk himself, saying that Edip Has-A-Name/Well-Established (Adı-Var)

Education

Halide Edip was educated by many private tutors at home on Ottoman literature, religion, philosophy, sociology, piano, English, French, and Arabic. Her first husband was one of her tutors. She was educated in a Greek kindergarten and learned Greek there. She became the first Muslim girl to be educated in the American College for Girls 1893-1901.

Religion

Muslim (She was educated in a Greek kindergarten, and was the first Muslim girl to be educated in the American College)

Transformation(s)

Her divorce from her first husband even though she loved him because he took on a second wife seems to be her first transformation. Her separation from her sons and joining the anti-colonialist nationalist struggle in Anatolia with her second husband Adnan Adıvar constitutes a second transformation that comes out in her memoirs.

She went to the United States of America twice and once to India following her contribution to the nationalist struggle-and continuing writing in the meanwhile. She went first to the United States in 1928, chairing a roundtable conference at the Williamstown Political Institute. (Her sons were already living there, and this was the first time they united after nine years after they were seperated). The second time was in 1932, at Columbia University Bernard College. She also gave lectures at Yale, Illinois, Michigan universities and published these lectures in Turkey titling it Viewing the West. When she was invited to India to the Islamic University Jamia Milia in 1935, she lectured at Delhi, Calcutta, Benares, Hyderabad, Aligar, Lahore and Peshawar Universities. She also published these lectures in Turkey titling it Indian Impressions.

In 1936, she published The Daughter of the Clown, the English original of her most famous, semi-authobiographic work, Sinekli Bakkal/ The Shop with the Flies. She won the CHP Award in 1943 and was the most pressing novels in Turkey. Upon her return to Istanbul in 1939, she was assigned by İsmet İnönü, the president then, to establish the English Philology Department at Istanbul University in 1940 and served as chair for ten years.

Contemporaneous Network(s)

Although Edip does not exclusively identify as a feminist and is even critical of the blue stocking suffragists in Britain, she was pro-suffrage and was also among the first women to be nominated even before women won the right to choose. She also expressed her admiration of women from all classes.

In addition, her divorce from her first husband was a feminist move that referred to her international/female friends, the key person among them was Ms. Dodd. Edip's ongoing relationship to Americans with whom she participated in processes of education decreased her estrangement and caused her to question her nationalism. For example, Miss Dodd, her teacher at the American college, was commemorated in her memoirs at the critical moments of Edip’s private and political lives. According to Edip, Miss Dodd helped Edip as when she divorced Salih Zeki, or when she needed a place to leave her boys during times of political turmoil. It was also Miss Dodd who helped Edip gain connections with women in Europe. Due to the lack of information during the years of occupation, Edip received important news such as the occupation of İzmir through Miss Dodd. Edip’s connection to people like Miss Dodd nourished Edip’s nationalism but at the same time prompted her to question “the inner meaning of” her nationalism, whether it could hurt others who were not Turks. Those who were not Turks who were dear to Edip were American and Armenian women, who entered her life in college and remained there for the rest of her life. In short, it was these women and the new projects of education they ventured together that invigorated a questioning of nationalism for Edip.

One of her female biographers -and assistant- Mina Urgan recalls that one time Edip related her melancholy to the “loss” of her first husband Salih Zeki Bey. Edip had divorced Zeki after he took on a second wife, when polygamy was a legal practice but widely unpracticed in Istanbul. Edip's seemingly feminist ideals, which she imagined in reference to her “international friends (as described in the above paragraph)” could not let her tolerate polygamy. Thus, she divorced him, without ever forgetting how she was offended. Afterwards she married Adnan (Adıvar) (1882-1955), a doctor who became a deputy in the last Ottoman and the first Turkish assemblies after their marriage.

Edip’s approach towards the memory of her first husband has struck analysts of her life. Although she remembered Zeki with bitterness every time, she could not refrain from mentioning his name in the most convoluted moments of her life. Her relationship with president Mustafa Kemal too, has not been very different from her relationship with her ex-husband. She both admired Mustafa Kemal’s frame of mind, and felt being “irretrievably wronged” by him. In fact, in her memoirs, when she indicates a marginalized political actor –one of “those wronged by him”- for the first time, she gives a short note on his tragic future in the hands of the prominent republican politicians (See for example The Turkish Ordeal, p. 401 and Türkün Ateşle İmtihanı, pp. 52, 74). İsmet İnönü, the second president, was perhaps the only man in this group to have compensated what he has done—excluding her--by calling Edip and her husband back from exile. Yet her presidential assignment in the English department even though she did not have any academic interests in this language, seems only to have urged her to review her past and the roles of these men in it over and over again.

In Memoirs of Halide Edip she distances herself from these men by combining private lives and politics. For instance, her remarks on her ex-husband's second marriage also reveal her opinion on educational policies exercised in the Ottoman empire (p.309). I have previously stated that Edip's narrative challenges and constitutes hegemonic forms of history. Thus, although she became an important figure in the nationalist struggle, she was also to be marginalised quickly due to her critical attitude. Like other autobiographical texts that belong to women, an analysis of Edip’s memoirs prove that nationalist history not only blocks the access to personal memoirs, but also feeds from them. In the case of Turkish history, nationalist history declares memoir-writers such as Edip (for the first world war period) and Sabiha Sertel (for the second world war period) traitors and by doing so, builds a wall between itself and their texts. However, certain periods in the historical flow cannot do without these texts: Edip's works are an irreplaceable part of the narratives of the passage to the republic, a key period in Turkish history.

less

Significance

Works/Agency

Edip’s declaration of self-doubt and inner dilemmas exposed her to harsh critique. With such transparency, she developed humanitarian attitude, which she enjoyed to express mostly in the context of her relations with international colleagues in her memoirs, and in her insightful novels.

Her autobiographical novel Ateşten Gömlek, (A Shirt of Fire) was printed as a series in 1922, when she was close to Mustafa Kemal. The book became an instant hit, and was made into a movie by 1923. This way it was to influence the nationalist narrative significantly. However fame for Edip was not to last long; for her ambition was regarded as a challenge to single-party politics, it was followed by self-exile. She composed her memoirs concerning the establishment period of the Turkish republic and her discontent with the radical transformations of both İnönü and Atatürk in English in exile. These memoirs could only be published in Turkish thirty six years later, in 1959.

Edip wrote A Shirt of Fire in 1922 during the War of Independence. This novel is a compact and more optimistic version of her memoirs in English (The Turkish Ordeal) and in Turkish (Türk’ün Ateşle İmtihanı). It follows the same sequence and has similar chapter headings with Türk’ün Ateşle İmtihanı. The sequence of events in both works is as such: the state of Istanbul after 1908, Edip’s decision become a revolutionary, the journey to Ankara, the new government, and the war of Independence. A Shirt of Fire, however, includes a final chapter titled Victory; this section is omitted in the memoirs. A Shirt of Fire was a title Yakub Kadri chose for one of his own novels, but changed the name of this novel after Edip revealed her intention to use this title as well. A shirt of fire both indicated love between men and women, and love for the country. Edip explains in the book that the title was shared between the two writers, like it was shared by men and women who “childishly insisted on calling their stories shirts of fire.” More than a decade later, in 1934, an Ottoman-Armenian feminist and anti-militarist writer, Zabel Yaseyan, published her own autobiographical fiction called A Shirt of Fire, Gırage Şabig in Armenian. Yaseyan’s book title indicated that wearing the shirts of fire was did not just burn Muslim men and women.

The film adaptation of A Shirt of Fire was in fact one of the first movies of the Turkish cinema industry and also the very first movie which casted a Muslim female actor. The film was also the first occasion where Muslim women appeared on screen. Halide Edip insisted that the leading role should be played by one. The film, like the book, was about the War of Independence and centered around the love of two men for the divorced heroine, played by Bedia Muvahhit (1897-1994). While the beautiful Bedia Muvahhit is shown in close-up shots, the war in the background is reflected onto the screen almost always from a distance, in contrast to the original narrative. However, while the novel has a lively and sentimental anti-war tone, the film is dominated by scenes of war.

An example of how Edip personalizes her political views is best revealed in her discussion of nationalism as well. For example, her revelation of her views on nationalism is accompanied by her questioning of this form of nationalism. She asks herself if her nationalism defeats her internationalism (Memoirs of Halide Edip, 317, 319, 321). Halide Edip’s autobiographies are not only evaluations of others’ weaknesses, but also of her own. By criticizing her own nationalism, she situates herself in the opposition to the mainstream despite her participation in the anti-colonialist nationalist struggle in the front and with her books. Another unique way that Edip follows in writing her autobiographies is the continuous description of her estrangement. She refers to herself by her first name Halide, whom she describes as a “black (for her black gown) and weak little woman” “among powerful men” in Türkün Ateşle İmtihanı. She relates her being the only woman among men to feelings of weakness and sometimes too much strength. She sometimes refers to her pending feelings as “a holy madness.”

List of works:

Seviye Talip (1910).

Handan (1912).

Mevut Hükümler (1918).

Yeni Turan (1912).

Son Eseri (1919).

Ateşten Gömlek (1922; translated into English as The Daughter of Smyrna or The Shirt of Flame).

Çıkan Kuri (1922).

Kalb Ağrısı (1924).

Vurun Kahpeye (1926).

The Memoirs of Halide Edib, New York-London: The Century, 1926 (published in English). Profile

The Turkish Ordeal, New York-London: The Century, 1928 (memoir, published in English).

Zeyno'nun Oğlu (1928).

Turkey Faces West, New Haven-London: Yale University Press/Oxford University Press, 1930.

The Clown and His Daughter (first published in English in 1935 and in Turkish as Sinekli Bakkal in 1936).

Inside India (first published in English in 1937 and in Turkish as Hindistan'a Dairin its entirety in 2014.)

Türk'ün Ateşle İmtihanı (memoir, published in 1962; translated into English as House with Wisteria).

Contemporaneous Identifications

She is the subject of many biographies.

Some of her books have been both composed and translated into the English language. German, Roman, French, Polish, Spanish, Modern Greek, Croatian, Hungarian, Italian and Romanian translations of the Clown and His Daughter and the New Turan (Hungarian) also exist. She is herself a translator of many books including Shakespeare's Hamlet, Nazım Hikmet's Letter to Taranta-Babu, and Mother by Jacob Abbott.

She is the subject of many dissertations and books in Turkish, English, French and German from the fields of Literature, Political Science, and Translation.

Reputation

Edip has always been a debated character, who was unlike any other. I have previously stated that her self-critical and open attitude about herself concerning her nationalism, her womanhood, her feminism, and her role in Turkifying Armenian children may have been considered a hint on others to continue critique. However, this self critical attitude, despite her wrongs, made her still a source of debate even now. Her political and author characters complemented each other. As Member of the Grand National Assembly In office 14 May 1950 – 5 January 1954 as the İzmir deputy from the Democrat Party first and then served as an independent deputy. On January 5, 1954, she published an article titled “Political Goodbye” in Cumhuriyet and resigning from this position and going back to the university again.

Edip's documentation of the anti-colonialist nationalist struggle was used in mainstream narratives of this history without the mention of her name, which was by then associated with demand for American mandate (already she was not the only one to advocate it for many delegates in the first two congresses that built the national struggle, after this option was ruled out, hers was the only name that kept being associated with it for decades). The nationalist questioning of family roots, or labelling her actions through her kinship status--being the daughter of a Jewish convert-- too includes a ridicule aimed at Edip's female traits. Attributing her a weak character complements perceiving her in terms of her father or husband, which points to a patriarchal understanding. goes unnoticed. Not only that but also Edip's skills as a novelist are highly criticized too. Her novels were continuously ridiculed with the declaration that both the writer herself and her female characters are ‘half women half men.’

Legacy and Influence

Edip wrote more than twenty-five novels and has had a deep impact on Turkish literature. In her novels and memoirs Edip conveys one of the most detailed descriptions of daily life and the development of events between the occupation of Izmir in 1919 and the Turkish victory in the War of Independence of 1922. She weaves these events with unconventional and interpenetrating narratives of herself and others, but when the nationalist history uses her writings, these are carefully picked out by the Turkish historians. As a result, this history is stripped from its social basis and transformed into a mere nationalist history that sacrifices, quite ironically, the social to prove its loyalty to the nationalist struggle. Other autobiographical accounts of the period, which are more carefully acknowledged, describe this period as a derivative of (the founder and first president of the republic) Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk)'s The Speech.

Mustafa Kemal's Nutuk (The Speech) was an autobiography, which provided details from his point of view into the history of the independence and foundation processes, with a focus on those who wronged him. Mustafa Kemal had provided Edip and other writers and professors like Yusuf Akçura with clues to his speech while they were soldiers of honour at the Western front, Mustafa Kemal’s front. This friendship experienced in war is where Halide Edip’s and Mustafa Kemal’s biographies, which would later constitute the bases for the national history narrative, collide. Mustafa Kemal revealed that his frame of mind and approach to politics was shaped by a critical way of thinking in this context. According to Edip, they shared this frame of mind in war and later in their autobiographies. Yet she asserts in Türkün Ateşle İmtihanı that Mustafa Kemal’s narrative, and the subsequent narratives based on his, are “one-sided,” while hers takes variety of factors into consideration.

There are countless schools, libraries and reading rooms named after her in Turkey, some of the examples of which are given below.

Most distinguished of these spaces is the National Library reading room:

http://www.millikutuphane.gov.tr/page/banko

another one:

https://foursquare.com/v/halide-edip-ad%C4%B1var-okuma-salonu/547acb39498ef6bf85e46084

The school in Çankaya: http://hedipadivar.meb.k12.tr/

Restaurants

Streets in Ankara and İstanbul.

University Campuses

http://heaal.meb.k12.tr/icerikler/yeni-universitelilerimiz_5468598.html

Cultural Convention Centers and awards associated with them

Mosque Complexes and architectural awards associated with them

Girls' Dormitories

less

Controversies

Controversy

When alive, the value of her novels were evaluated in relation to her political standing. She was excluded, but she herself too, participated in various politics of exclusion. For instance, her approach to nationalism goes between pro-war nationalism when she mentions Greeks and an anti-war coexistentionalism in the context of Armenians. Interestingly, it is her pro-war sentiments that are singled out and used by both nationalist texts and her biographers, and her antiwar statements that go unnoticed. For example, the shots of fire that she heard from a distance becomes a part of Turkish history while her efforts to distance herself from war never makes its way into history books. She considered her passion with education as a channel for uniting Armenian and Turkish mothers. This was probably a way of resolving the great psychological crisis she suffered from as an agent of the Ottoman state in Syria, managing an orphanage for Armenian children who were able to flee from the genocide. The extent of her interest in education included teaching at and directing schools, as well as keeping a life-long dialogue with her own teachers from the American college. In this line she, participated in the Turkish- and Armenian-American war orphans projects that took place in Syria, Lebanon, and Damascus. Edip overtly associates her participation in these projects with feelings of motherhood. In other words, she uses motherhood to express her desire for peace in an age of war.

Conversion is also one of the main subjects of her most well-known novel Sinekli Bakkal (The Clown and His Daughter) takes place in the late Ottoman era, and its heroine is a young woman who marries and Italian man--after converting him to Islam. The novel was already published a number of times before Edip’s death in 1964--in 1936, 1941, 1942, 1943 and 1957--and articles about this and other novels were published throughout this period. Several articles by distinguished writers were published in Yücel magazine. The general tendency by Yücel writers was to celebrate Edip’s novels rather than critique them; however, later on a much more negative discourse was adopted in other magazines. For example, in the articles published in Varlık in 1947, Edip’s public image was disconcerted. In one such case, the writer criticized Edip for imagining herself in the role of a “professor-know-it-all” who wrote about women who were “ugly, self-righteous, full of feminist ideas,” “half man half woman,” “women whom no man can really like or love.” However, In the 1990s, long after Edip’s death, the unsympathetic tone was to be replaced by an attitude similar to the one expressed by the initial reactions. These latter critiques finally emphasized her unique conceptualizations of femininity.

Edip paid the price of having exceptional publicity by being called a prostitute, a salon lady who has no regards for the peasants, and the daughter of a servant by Mevlanzade Rıfat a prominent Kurdish and pro-feminist figure in the publishing life. These insults that came from the critics of her novels in the 1940s as well as her fellow political activists were not the only denouncements Edip endured. As she was a woman in her forties, the critiques emphasized that she had lost her youth and claimed that “a woman that age” was “uselessness.” In the eye of these alleged literary critics, she was “a creature both man and woman” or worse, “a man-woman complied with the satisfaction of neither her womanhood nor manhood.” The critics did not bother to explain the connection between the importance of being a pure woman and being a good writer, or an important figure.

In short, since most of these critiques have focused on Edip’s womanly or non-womanly traits, they are gendered. Alternatively, examining her memoirs, supported with her novels, which construct and question the mainstream nationalist narrative, could offer a tool to understand how gender dynamics really worked. For example, unmentioned by her critics, Edip's account focuses on the identities created by motherhood, within and beyond the possibilities of nationalism.

less

Bibliography

Primary (selected):

Adak, Hülya. 2003. “National Myths and Self-Na(rra)tions: Mustafa Kemal’s Nutuk and Halide Edib’s Memoirs and The Turkish Ordeal” South Atlantic Quarterly, 102: 2-3, Spring/Summer.

Akşin, Sina. Türkiye'nin Yakın Tarihi, (Ankara: İmaj Yayıncılık, 2006).

Araboğlu, Aslı. “Multi-cultural Identity of Translator and Reflection of Identity to Translation Çevirmenin Çok Kültürlü Kimliği ve Kimliğin Çeviriye Yansıması,” International Journal of Languages’ Education and Teaching Volume 7, Issue 4, December 2019, p. 92-103. DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.29228/ijlet.38912

Arslan, Savaş. “Turkish Hamlets,” Shakespeare. v4- Issue 2 283, 2008, 157-168. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450910802083468

Günyol, Vedat. “Halide Edip’le Bir Konuşma,” Yücel 15 (1942): 8.

Günyol, Vedat. “Tatarcık,” Yücel 10, no. 558-9 (1939-40): 179-187.

Mevlanzade, Rıfat. Türkiye İnkılabının İçyüzü (Istanbul: Pınar Yayınları, 2000).

Milas, Herkül. Türk Romanı ve Öteki: Ulusal Kimlikte Yunan İmajı (Istanbul: Sabancı, 2000).

Sertel, Sabiha. Roman Gibi (1919-1950), (Istanbul: Ant Yayınları, 1966).

Sönmez, Emel. "The Novelist Halide Edib Adivar and Turkish Feminism." Die Welt des Islams, v14, Issue 1/4 (1973): 81–115.

Web Resources (selected):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Halide_Edib_Ad%C4%B1var

American College Library Page Dedicated to Edip

Comment

Your message was sent successfully