Birth

Gertruda was born around 1025, at one of the royal residences of Poland, perhaps Kraków.

Education

Death

Most scholars place Gertruda’s death on 4 January 1108, when the same chronicle records that “Sviatopolk’s mother” died

Religion

Eastern Orthodox Christianity , Latin ChristianityGertruda is considered by many scholars to have been not only the first female writer in Poland, but the first native-born Polish writer.

She is important, foremost, as the commissioner, and perhaps even writer, of a still-surviving prayer-book, the Codex Gertrudianus. Not only did Gertruda commission this lavish prayer-book, but she also patronized the Monastery of the Caves in Kyiv and its church of the Dormition of the Mother of God (1073-1077; consecrated in 1089), interceding on behalf of its monks before her husband who threatened to dissolve the monastery. On chronological grounds, it is also possible that Gertruda can be identified with the anonymous princess who founded a female monastery to Saint Nicholas in Kyiv according to the late eleventh-century Life of Saint Feodosii.

Personal Information

Name(s)

Gertruda Mieszkówna; Gertruda (Gertrude) of Poland (sometimes identified as “Olisava” or “Helena”; see “Controversies” belows)

Date and place of birth

Gertruda was born around 1025, at one of the royal residences of Poland, perhaps Kraków.

Date and place of death

The last certain reference to Gertruda in the written record is in the twelfth-century Rus’ Primary Chronicle (also known as the Tale of Bygone Years) under the year 1085, when she was captured by Prince Vladimir (Volodimer) Monomakh, an enemy of her son, prince Yaropolk-Peter (d. 1086/1087) and taken as a hostage to Kyiv (Kiev). Most scholars place Gertruda’s death on 4 January 1108, when the same chronicle records that “Sviatopolk’s mother” died, but as discussed below, there is some controversy as to whether this record refers to Gertruda or not. If so, she would have been in her eighties at the time of her death. Her place of death is unknown.

Family

Mother: Gertruda was the daughter of Queen Richeza (d. 1063), an important female ruler and religious patron in her own right. Richeza was descended from German-Byzantine nobility and royalty, being the daughter of Count Palatine Erenfried Ezzo of the Rhine (d. 1034) and Mathilda (d. circa 979-1025), who was, in turn, the youngest daughter of the German Emperor Otto II (d. 955) and the Byzantine princess Theophano (d. 991). Gertruda had at least one sibling, the future King Kazimierz I ‘the Restorer’ of Poland (d. 1058).

Father: Gertruda’s father was King Mieszko-Lambert II of Poland (d. 1034).

Marriage and Family Life

Gertruda’s maternal aunts (Richeza’s sisters) were all powerful abbesses in the Rhineland: her aunt Theophanu (d. 1056) ruled the abbeys of Essen and Gerresheim, her aunt Heylewig ruled the monastery of Saint Quirin in Neuss (d. 1076), her aunt Mathilda (d. ?) ruled the abbeys in Dietkirchen (now part of Bonn) and Vilich (both dedicated to Saint Peter), and her aunt Ida (d. 1060) ruled as abbess at Saint Mary’s in Gandersheim (later, from about 1049, she also served as abbess of Saint Mary’s on the Capitol in Cologne).

Gertruda married the Rus’ prince Iziaslav Yaroslavich sometime between 1039-1050 (the date of the marriage is a subject of scholarly controversy). Whether or not Gertruda was the mother of Iziaslav’s sons, Mstislav Iziaslavich (d. 1069) and Sviatopolk-Michael Iziaslavich (d. 1113), is also disputed. She certainly was the mother of Yaropolk-Peter (d. 1086/1087). In her surviving personal prayer-book, a source of literary and cultural importance, Gertruda refers to Yaropolk-Peter as “my only son” (in Latin: “unicus filius meus”), although some scholars have interpreted these words to mean that Yaropolk-Peter was Gertruda’s most beloved son.

Through her marriage to Iziaslav, Gertruda became the sister-in-law of a number of illustrious women, including Anna Yaroslavna (d. 1075/1079), queen-consort of Henri I of France (d. 1060) and Anastasia Yaroslavna (d. after 1074), queen-consort of András I of Hungary (d. 1060).

Education

Gertruda is considered by many scholars to have been not only the first female writer in Poland, but the first native-born Polish writer. Forced to flee Poland for political reasons with her mother Queen Richeza in 1031, Gertruda was probably educated at one of the monasteries around Cologne where her maternal aunts ruled as abbesses. Here, Gertruda received a thorough education, becoming familiar with church services and the Latin language.

The fact that she was well educated is suggested by her surviving personal prayer-book, the Codex Gertrudianus, or, according to its older names, the Egbert Psalter or Trier Psalter (Cividale del Friuli, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, codex 136). This manuscript originally consisted of a tenth-century psalter made for Archbishop Egbert of Trier (r. 977-993). How exactly Gertruda acquired this psalter remains debated. She may have acquired it as a dowry item from her mother Richeza, or during one of her long journeys throughout Western Europe during two periods of exile following her marriage: 1068-1069 and 1073-1077. The newer name for the manuscript, the Codex Gertrudianus, reflects the fact that Gertruda greatly added to the psalter and made it into her own personal prayer-book. She commissioned over ninety prayers in Latin, which she added throughout the tenth-century psalter, both in the available margins and blank spaces of the original book and in fifteen new pages added to the beginning of the manuscript. She further enriched the book with a church calendar and five Byzantine-style miniatures, probably made in the period from 1078 to 1086/1087 (see further below).

Religion

Due to two long periods of exile from Rus’ (from 1068 to 1069 and 1073-1077), Gertruda moved between the worlds of Latin Christianity (medieval Catholicism) and Eastern Orthodoxy, while travelling to Poland and Germany. Her exact religious identity remains a point of scholarly discussion, but her prayer-book shows that Gertruda drew on elements of both Western and Eastern Christian spirituality in her life.

Transformation(s)

During her periods of exile from Rus’ in 1068 to 1069 and 1073-1077, Gertruda actively helped her husband Iziaslav Yaroslavich to regain the throne of Kyiv from his younger brothers Sviatoslav and Vsevolod. She sought assistance first from her nephew, King Bolesław II of Poland, then from Emperor Henry IV. Finally in 1075, Gertruda and Iziaslav’s son, Yaropolk-Peter, went to Rome to seek the help from Pope Gregory VII (r. 1073-1085). Since Gregory’s surviving letter of 17 April 1075, taking Rus’ under the symbolic protection of Saint Peter, is addressed both to Iziaslav (whom Gregory calls by his Orthodox baptismal name of “Demetrius”) and to Gertruda (called simply Demetrius’ “queen”), several scholars suggested that Gertruda played a role in persuading her husband to turn to the pope for political help.

After the death of Sviatoslav in 1076, Gertruda was able to return to Rus’ with her husband Iziaslav. When he died in battle, in 1078, Gertruda went to live in western Rus’ with her son Yaropolk-Peter.

Contemporaneous Network(s)

The future fate of Gertruda’s prayer-book shows the role played by networks of women in the Middle Ages as cultural ambassadors, bringing books and ideas with them from one end of Europe to the other. Her prayer-book, the Codex Gertrudianus, was returned to Poland after Gertruda’s death, probably by her (step)granddaughter Sbyslava Sviatopolkovna who married Bolesław III Wry-mouth of Poland in 1103. At Sbyslava’s death, the manuscript was donated to the Swabian monastery of Zwiefalten. From Zwiefalten, it came into the possession of Saint Elizabeth of Thuringia (1207-1231), who likely received the manuscript from her mother, Gertruda of Andech, descended from the counts of Andech and Berg, patrons of Zwiefalten monastery. In 1229, Elizabeth donated the manuscript to the Cathedral of Cividale, and the manuscript has remained in this Italian city to the present day.

less

Significance

Works/Agency

Gertruda is important foremost as the commissioner, and perhaps even writer, of a still-surviving prayer-book, the aforementioned Codex Gertrudianus. While earlier scholarship considered the manuscript’s eleventh-century prayers to have been written in Gertruda’s own hand, today many scholars assume that they were written for Gertruda by a chaplain, though explicitly for her ownership as testified by the use of feminine forms of adjectives throughout and the personalized phrase “ego Gertruda” (Latin: “I, Gertruda”) used in the prayers. Other scholars, however, such as Artur Andrzejuk, continue to maintain that Gertruda was well-educated enough to compose her prayer-book by her own hand. This manuscript, enriched by colourful miniatures and expensive golden ink, is a priceless monument of eleventh-century Rus’-Polish artistic and spiritual culture.

Not only did Gertruda commission this lavish prayer-book, but she also patronized the Monastery of the Caves in Kyiv and its church of the Dormition of the Mother of God (1073-1077; consecrated in 1089), interceding on behalf of its monks before her husband who had threatened to dissolve the monastery. On chronological grounds, it is also possible that Gertruda can be identified with the anonymous princess who founded a female monastery to Saint Nicholas in Kyiv according to the late eleventh-century Life of Saint Feodosii.

Contemporaneous Identifications

Only Gertruda’s own prayer-book, written in the first person, preserves a record of her name (whether a contemporary graffito refers to her is debated; see ‘Controversy’ below). Other sources identify her by title or in relation to her male relatives. For example, in the aformentioned letter written in Latin on 17 April 1075, Pope Gregory VII addressed Gertruda as the queen (“regina”) of Rus’. The twelfth-century Rus’ Primary Chronicle (also known as the Tale of Bygone Years) identifies her by familial relations as the sister of Kazimierz of Poland and mother of Yaropolk. The Old East Slavic Paterik, a collection of stories about the Monastery of the Caves in Kyiv, written in the thirteenth century, but containing older tales, refers to her as the “prince’s wife”, or simply “the Polish woman” (“Liakhovitsa”).

Reputation

Few sources mention Gertruda’s life directly except for her personal prayer-book. She is portrayed positively as an intercessor on behalf of the Orthodox monks of the Kyivan Monastery of the Caves in the monk Nestor’s Life of the igumen (abbot) Saint Feodosii (d. 1074), probably written by the monk Nestor in the 1080s. In this Life, Gertruda’s husband Iziaslav Yaroslavich becomes very angry when Feodosii’s successor, igumen Nikon of the Caves Monastery (d. 1088), admitted two men of the prince’s household to the monastery without Iziaslav’s permission. As a result, Iziaslav Yaroslavich threatened to imprison Nikon and to destroy the hermit’s cave. The monks of the Caves Monastery responded to this threat by making preparations to move away to another area. But the story relates that “the prince’s wife,” who can almost certainly be identified with Gertruda, intervened to save the monastery. Her words cause Iziaslav to change his mind and beg the monks to return. Gertruda’s protection of the monastery is told again in the thirteenth-century story of “the venerable Moisei (Moses) the Hungarian,” written in the Caves Monastery.

Legacy and Influence

Since Gertruda’s lifetime, special interest in her life has been re-animated only in the twentieth century. Serious scholarship on the most important source of Gertruda’s life, the Codex Gertrudianus, began in 1901 with the publication of a study by Heinrich V. Sauerland and Arthur Haseloff. However, earlier scholarship focused mainly on the older part of the Codex, the tenth-century psalter made for Archbishop Egbert of Trier. Recent work from the 1990s onward by Teresa Michałowska, Brygida Kürbis, Małgorzata Malewicz, Artur Andrzejuk, Engelina Smirnova, Małgorzata Smorąg Różycka, Grzegorz Pac, and others, turned attention to the eleventh-century part of the manuscript and to the person of Gertruda. Teresa Michałowska argued that Gertruda’s prayer-book can be read as a kind of spiritual autobiographical text, similar to Augustine of Hippo’s late fourth-century Confessions. While the language of the prayers themselves is often conventional, since they rework pre-existing prayers or paraphrase established liturgical formulas, Michałowska argues that the arrangement and ordering of the prayers was a conscious choice on Gertruda’s part, and reflects the Polish princess’ life experiences in exile, or her worries about the fate of her beloved son Yaropolk-Peter. Scholars such as Artur Andrzejuk and Witold Sadowski have been re-examining Gertruda in the context of Poland’s literary canon, seeing her as the first native-born Polish author. This distinction is usually accorded to Bishop Vincent Kadłubek of Kraków (d. 1223), author of the Chronicle of the Poles (Chronica Polonorum), written two hundred years after Gertruda’s prayer-book.

New and unfolding information and/or interpretations The date(s) of composition, political and spiritual content of Gertruda’s prayers and of the miniatures which she commissioned in her prayer-book remain a topic of ongoing scholarly discussion.

Current Identification(s)

Gertruda’s life has been included in works on art history, female patronage, the role of women in early medieval Polish society, female spirituality, development of writing in Poland, and the history of relations between Eastern and Western Christianity during the Middle Ages.

Clusters

Gregory VII; Piast dynasty of Poland; ruling clan of Rus’ (Riurikid dynasty); family of Yaroslav the Wise and Ingigerd of Sweden; family of Richeza of Poland; Ottonian dynasty; Theophano.

Search Terms

Gertruda of Poland (Gertruda Mieszkówna); prayer-book; psalter; Codex Gertrudianus; Trier Psalter; Egbert Psalter; Rhineland; Cologne; Kyiv (Kiev); Kraków (Cracow); Rome; Gregory VII; Iziaslav Yaroslavich; Richeza of Poland; Piast dynasty of Poland; ruling clan of Rus’ (Riurikid dynasty); Monastery of the Caves; St Nicholas Monastery; Saint Feodosii (Theodosius); medieval; eleventh century; twelfth century; 1075; female monasteries.

References in existing schemas

Anna Yaroslavna (Anne de Kiev)

less

Controversies

Controversy

There are two main sources of controversy relating to Gertruda’s life in light of how she was affected by the Church Schism, the developing estrangement between Eastern Orthodoxy and Latin Christianity (modern Roman Catholicism).

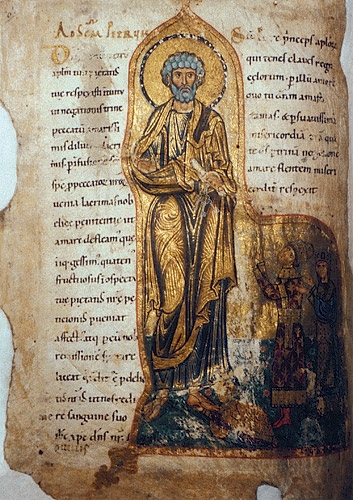

The first concerns Gertruda’s religious identity and her alleged role in “converting” her son Yaropolk-Peter to Roman Catholicism, based partly on the miniatures in the Codex Gertrudianus, one of which depicts Gertruda, her son Yaropolk-Peter, and an unnamed woman at the feet of Saint Peter (folio 5v). Soviet historian V. L. Yanin argued that this miniature depicts Yaropolk-Peter’s submission to Rome. More recently, however, scholars such as Malewicz and Kürbis have disputed this reading, showing that Gertruda’s veneration of Saint Peter did not mean a unilateral declaration of allegiance to Roman Catholicism among her family. During the eleventh century, Saint Peter was not just associated with the popes of Rome, but also with the concept of repenting for one’s sins.

Connected with this issue of the religious context of the images in the Codex Gertrudianus is a now resolved debate on where the eleventh-century miniatures in this manuscript were made: Germany, Rome, Rus’, or Poland. The most recent iconographical studies have established Rus’ as their most probable place of origin.

The second controversy relating to Gertruda concerns a graffito in Kyiv’s Saint Sophia Cathedral, which states, “Lord, help thy servant Olisava, Princess of Rus’, Sviatopolk’s mother.” According to the widely-cited 1963 thesis of V. L. Yanin, this graffito indicates that Gertruda was renamed Olisava (a form of Elizabeth), following her marriage to Iziaslav in Rus’, and that therefore that she was obliged to convert formally to Eastern Orthodoxy. Others, such as Karol Górski, have suggested that “Olisava,” Sviatopolk’s mother, must have been Iziaslav’s previous wife and hence a different woman from Gertruda. On the basis of an appearance in the eleventh-century calendar of the Codex Gertrudianus and in three prayers in this same manuscript addressed to Saint Helena, mother of Constantine, Russian scholar Alexandr Nazarenko has proposed more recently (2001) the alternative suggestion that Gertruda could have been renamed “Helena” (or “Elena”) in Rus’ (without, however, accepting any need for re-baptism).

less

Bibliography

Primary (selected):

Heppell, Muriel, trans. The Paterik of the Kievan Caves Monastery. Preface by Dimitri Obolensky. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute / Harvard University Press, 1989.

Modlitwy księżnej Getrudy z Psałterza Egberta z kalendarzem / Liber Precum Gertrudae Ducissae e Psalterio Egberti cum Kalendario, eds. Małgorzata H. Malewicz and Brygida Kürbis, notes by Brygida Kürbis, Monumenta Sacra Polonorum, vol. 2 (Kraków: Polska Akademia Umiejętności / Academia Scientiarum et Litterarum Polona, 2002).

Psalterium Egberti: facsimile del ms. CXXXVI del Museo archeologico nazionale di cividale del Friuli, 2 vols. (vol. 1: commentary, vol. 2: facsimile), ed. Claudio Barberi (Cividale, Italy: Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali […], 2000).

The Correspondence of Pope Gregory VII: Selected Letters from the Registrum, trans. and intro. Ephraim Emerton (New York: Columbia University Press, 1932)

The Russian Primary Chronicle: Laurentian text. Trans. and ed. Samuel Hazzard Cross and Olgerd P. Sherbowitz-Wetzor. Cambridge, MA: Medieval Academy of America, 1953.

Archival resources (selected):

Cividale del Friuli, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Archivi e Biblioteca, codex 136.

Web resources (selected):

Gertruda Mieszkówna i jej Manuskrypt [Gertruda, Daughter of Mieszko, and Her Manuscript] Ed. Artur Andzejuk <http://www.gertruda.eu/>. (Multi-lingual website (including English) with downloadable pdf articles on Gertruda’s life and her prayer-book and Polish / Latin edition of Gertruda’s prayers).

Rusian Genealogy Web Map. Compiled by Christian Raffensperger, with technical assistance by David J. Birnbaum. Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute (HURI), with technical support provided by HURI and the Center for Geographical Analysis at Harvard University.< http://gis.huri.harvard.edu/rusgen/> (Website with genealogical data on Gertruda’s family through marriage and map showing marriages of Rus’ women across Europe, includes link to website on Gertruda’s genealogy).

Salterio di Egberto (Codex Gertrudianus). < https://www.librideipatriarchi.it/libri/salterio-di-egberto-codex-gertrudianus

(Complete digitized copy of Gertruda’s prayer-book)

Comment

Your message was sent successfully