Birth

December 4, 1822

Death

April 5, 1904

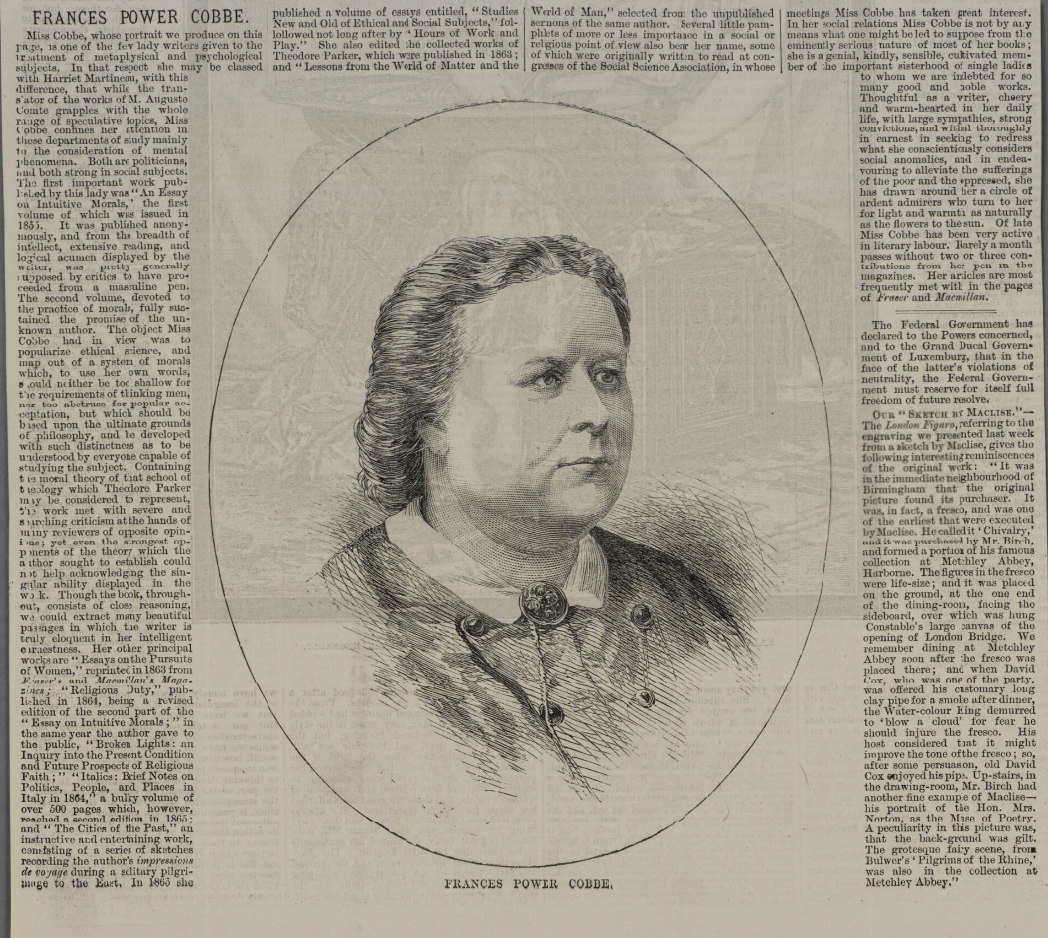

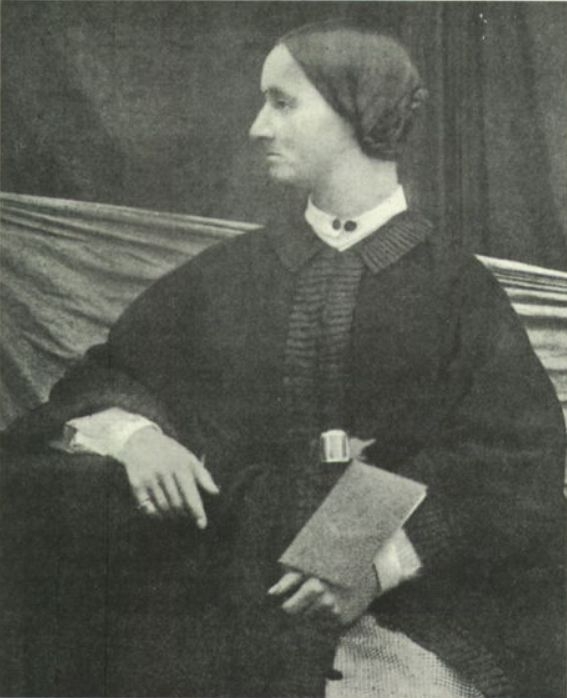

Frances Power Cobbe was a well-known philosopher, writer, and campaigner during the Victorian period in Britain. Born in Ireland and working mainly in England and then Wales, she published around two hundred journal articles and twenty books on topics on moral theory, religion, animal ethics, feminism, the mind and cognition, political and current affairs, welfare reform, and many other topics. The leader of the anti-vivisection campaign, she founded two anti-vivisection organisations that still exist today. Vivisection is the practice of performing operations on live animals for the purpose of scientific research or experimentation. Partly through her seven years of writing editorials for the major daily newspaper Echo, she reached a huge audience.

Personal Information

Name(s)

Frances Power Cobbe

Date and place of birth

December 4, 1822, Newbridge House, Donabate, County Dublin

Death and place of death

April 5, 1904, Hengwrt, Wales

Family

Mother:

Frances Conway (1777–1847), daughter of Captain Thomas Conway

Father:

Charles Cobbe (1781–1857), High Sheriff of County Dublin. He was grandson of Charles Cobbe (1687–1765), Archbishop of Dublin and Primate of Ireland

Marriage and Family Life

Frances Power Cobbe had four older brothers: Charles Cobbe (1811-1886), Thomas Cobbe (1813-1882), William Cobbe (1816-1911), and Henry Cobbe (1817-1898). She grew up in the family home in Newbridge House near Dublin. After her mother died, she became her father’s housekeeper, except when he expelled her from the home due to religious disagreements. After her father died in 1857, leaving her an annuity, she travelled the Near East and Europe unaccompanied, before returning to Bristol to live and work with the educational reformer Mary Carpenter (1807–1877). However, this did not suit Cobbe. She then spent extended periods in Italy in the early 1860s, joining a circle of independent women which included Charlotte Cushman (1816-1876), Matilda Hays (1820-1897), Harriet Hosmer (1830-1908), and the Welsh sculptor Mary Lloyd (1813–1896) who soon became Cobbe’s partner. By 1865 Cobbe was earning enough from writing to buy the home in Chelsea, London, where she and Lloyd settled. They were publicly accepted as a couple. In 1884 they retired to Hengwrt in Lloyd’s native Wales, where Cobbe remained after Lloyd’s death in 1896.

Education (short version)

Cobbe was educated mainly at home by governesses, with a year at finishing school in Brighton. She then undertook a rigorous programme of self-education.

Education (longer version)

Cobbe was educated mainly at home by governesses, then spent a year at finishing school in Brighton. The curriculum covered English, French, German, Italian, music, dance, and Bible study. Returning to the family home, Cobbe undertook a rigorous programme of self-education. Her family library had a large collection in religion and theology which she used, and by subscribing to several libraries, she taught herself history, classical and modern literature, ancient philosophy, architecture, and astronomy. She took lessons in Greek and geometry, and studied the world religions in available translations.

Religion

Cobbe was brought up evangelical but underwent a crisis of faith. Having discovered the American Unitarian theologian Theodore Parker, she turned to Theism, an unorthodox form of Christianity. Like the Unitarians, Cobbe regarded Jesus as a moral teacher and not literally divine, but she conceived Theism as broader than Unitarianism, based on reason and intuition, and capable of appealing to many believers across sectarian divides.

Transformation(s)

Cobbe gravitated towards an intellectual life early on. Witnessing the Great Famine (1845–1852), and losing her beloved mother when young, she sought a religious framework to make sense of suffering and to give hope for reunion with loved ones in the afterlife. Her Eastern travels, periods in Italy, and interactions with role-models like the esteemed scientist Mary Somerville (1780–1872) shaped her identity as an independent intellectual woman. Her time with Mary Carpenter was also important, convincing Cobbe that her vocation was to effect change by writing, rather than in direct practical work.

Cobbe defied the gendered expectations of her time. She wrote on philosophy and theology, and her first book was a treatise on moral theory. She published prolifically and supported herself through her writing. She wrote three leaders weekly for the London daily newspaper The Echo from 1868 to 1875, who gave her a ‘room of her own’ for penning her columns. She lived publicly with another woman, Mary Lloyd. Through her supporters, she was able to exert direct influence on parliamentary debates.

Contemporaneous Network(s)

Cobbe belonged to a vast range of networks. In Italy, her circle numbered Harriet Hosmer and Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806–1861). She dedicated her 1863 book Essays on the Pursuits of Women to a trio: Mary Somerville (representing the pursuit of knowledge), Mary Carpenter (representing moral action), and Hosmer (representing art). By then, Cobbe was friends with Somerville and became ghost co-author of her 1873 Personal Recollections of Mary Somerville, alongside her daughter Martha Somerville (1813–1879).

In London, from the mid-1860s onwards, Cobbe was active in feminist circles. Initially on the executive committee of the London National Society for Woman Suffrage, she left due to disagreements with Helen Taylor (1831–1907) and Lydia Becker (1827–1890). Cobbe also joined the second Married Women’s Property Committee. She contributed to Josephine Butler’s important anthology Woman’s Work and Woman’s Culture (1869), and her published critiques of domestic violence expedited legislation passed in 1878. Her other intellectual women friends included Julia Wedgwood (1833–1913) and Vernon Lee (1856–1935). Cobbe’s work was favourably received in many other countries, for instance in North America where Julia Ward Howe (1819–1910), Louisa May Alcott (1832–1888), and Caroline Earle White (1833–1916) were heavily influenced by Cobbe.

The men to whom she was closest included the Unitarian theologian James Martineau (1805–1900) (the brother of Harriet Martineau [1802–1876]) and the geologist Sir Charles Lyell (1797–1875). In the late 1860s, she was friends with Charles Darwin (1809–1882), and earlier she received support in her writing career from John Stuart Mill (1806–1873). Another good friend was Keshub Chunder Sen (1838–1884) from the Hindu reform movement the Brahmo Samaj.

From the 1860s onwards, Cobbe started to agitate for animal welfare. After one of her dogs was lost and rescued by the Battersea Dogs’ Home, founded in 1860 by Mary Tealby (1801–1865), she authored Confessions of a Lost Dog to promote the institution. Her growing worries about vivisection led her to draft legislation to restrict the practice, together with Lord Shaftesbury (1801–1885) and John Henniker-Major (1842–1902). In 1876, she founded the Victoria Street Society for the Protection of Animals Liable to Vivisection, together with Shaftesbury, George Hoggan (1837–1891), Frances Wedgwood (1800–1888, Julia Wedgwood’s mother), Leslie Stephen (1832–1904), and others. Later, when she thought the society had lost its radical edge, she founded a new organisation, the British Union for the Total Abolition of Vivisection (f. 1898).

Throughout, Cobbe combined membership in supportive female networks with inclusion in mainstream male networks. She forged pragmatic links with powerful men through whom she thought reforms could be best achieved.

less

Significance

Works/Agency

Cobbe authored around 200 journal articles, placing her at the heart of periodical culture. The journals she published in most often were Fraser’s Magazine, the Theological Review, and the Contemporary Review. She also published 20 books:

An Essay on Intuitive Morals. 2 vols. London: Longmans, 1855 and 1857.

Essays on the Pursuits of Women. London: Emily Faithfull.

The Cities of the Past. London: Trübner, 1864.

Broken Lights: An Inquiry into the Present Conditions and Future Prospects of Religious Faith. London: Trübner, 1864.

Italics: Brief Notes on Politics, People and Places in Italy, in 1864. London: Trübner, 1864.

Studies New and Old of Ethical and Social Subjects. London: Trübner, 1864.

Hours of Work and Play. London: Trübner, 1867.

Confessions of a Lost Dog. London: Griffith and Farran, 1867.

Dawning Lights: An Inquiry into the Secular Results of the New Reformation. London: Whitfield, 1868.

Darwinism in Morals, and Other Essays. London: Williams and Norgate, 1872.

The Hopes of the Human Race. London: Williams and Norgate, 1874.

False Beasts and True: Essays on Natural (and Unnatural) History. London: Ward, Lock, and Tyler, 1876.

Re-Echoes. London: Williams and Norgate, 1876.

The Age of Science: A Newspaper of the Twentieth Century. Signed ‘Merlin Nostradamus’. London: Ward, Lock and Tyler, 1877.

The Duties of Women. London: Williams and Norgate, 1881.

The Peak in Darien, with Some Other Inquiries Touching Concerns of the Soul and Body. London: Williams and Norgate, 1882.

The Scientific Spirit of the Age. London: Smith and Elder, 1888.

The Modern Rack: Papers on Vivisection. London: Swan Sonnenschein, 1889.

Life of Frances Power Cobbe. 2 vols. London: Bentley, 1894.

Cobbe edited the collected works of Theodore Parker (14 vols., 1863) and was on the editorial team of two journals, The Zoophilist, founded 1881, and The Abolitionist, founded 1899.

Reputation

In her lifetime, Cobbe was held in high regard, and seen primarily as a philosophical and religious thinker. Over time, she became more concerned with animal welfare and by the time she died she was increasingly seen in that light. Her anti-vivisectionism from the 1870s onwards diminished her reputation in the eyes of many scientists and medical practitioners, including those who defended vivisection in parliament against Cobbe’s proposals, centrally Charles Darwin and Thomas Henry Huxley (1825–1895). In the twentieth century, she was almost entirely forgotten, remarkably so given her reputation in the Victorian era. She has been rediscovered since the 2000s, but despite scholars’ efforts, she remains little known today.

Legacy and Influence

Cobbe’s two largest legacies are the two anti-vivisection organisations she founded, still existing today under new names. The Victoria Street Society became the National Anti-Vivisection Society (https://www.navs.org.uk/home/), and the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection is now part of Cruelty Free International (https://crueltyfreeinternational.org). Both commemorate Cobbe on their websites.

She is remembered by a plaque in Harris Manchester College, Oxford University (https://www.hmc.ox.ac.uk/article/women-who-made-harris-manchester-college) and on the statue of Millicent Fawcett in Parliament Square, London, amongst other suffragists (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Statue_of_Millicent_Fawcett). There is a Frances Power Cobbe Professorship of Animal Theology at the Graduate Theological Foundation, Oxford University, held by Clair Linzey.

less

Controversies

Controversy

The biggest controversy surrounded vivisection. Cobbe spearheaded the campaign to bring in regulatory legislation. But when the Cruelty to Animals Act 1876 became law, Cobbe was bitterly disappointed, as her proposals had been heavily watered down. She began to campaign for outright prohibition of vivisection. This ended many of her previous friendships–for instance, with Charles Darwin. In 1890, she helped to produce the Black Book of British Vivisectors, which publicly named and shamed many scientists and doctors. The community of ‘men of science’ reacted with outrage. Meanwhile the anti-vivisection movement gathered tens of thousands of members. The issue peaked shortly after Cobbe’s death with the Brown Dog Riots in London (1907–1910).

The vivisection controversy intersected with Cobbe’s dispute with Darwin. He eagerly solicited her published response to his book The Descent of Man (1871). But Cobbe was critical, arguing that evolutionary ethics justified sacrificing the weak to promote the health and fitness of the social group. Her friendship with Darwin limped on but they fell out again, conclusively, over vivisection.

New and Unfolding Information and/or Interpretations

Recent research on Cobbe encompasses two biographies, plus books on Cobbe as a feminist writer, religious and moral thinker, and philosopher. Cobbe figures into accounts of Victorian feminism and animal welfare campaigning. There is growing interest in her view that patriarchal violence towards women and scientific cruelty to animals were intrinsically connected.

less

Clusters & Search Terms

Current Identification(s)

Cobbe is mostly found in accounts of Victorian feminism and suffragism, animal welfare activism, and print and periodical culture. Most often, she is described as a reformer, activist, writer, and journalist. Newly emerging scholarship also identifies her as a moral and religious philosopher.

Clusters

London National Society for Women’s Suffrage

Married Women’s Property Committee

Victorian feminism

Anti-vivisectionism, animal welfare activism

Women in history of philosophy

Search Terms

Women philosophers, Victorian feminism, Victorian, Irish feminism, Anglo-Irish women, women journalists

less

Bibliography

Primary (selected):

Cobbe’s books are listed above under the section on her significance.

Secondary:

Donald, Diana. 2019. Women Against Cruelty: Protection of Animals in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Hamilton, Susan. 2006. Frances Power Cobbe and Victorian Feminism. London: Palgrave.

Hamilton, Susan, ed. 2004. Introduction to Animal Welfare and Anti-Vivisection 1870-1910, Vol. 1: Frances Power Cobbe. London: Routledge.

Li, Chien-Hui. 2023. Frances Power Cobbe (1822–1904). In Animal Theologians, ed. Andrew Linzey and Clair Linzey. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mitchell, Sally. 2004. Frances Power Cobbe: Victorian Feminist, Journalist, Reformer. Charlottesville VA: University of Virginia Press.

Peacock, Sandra J. 2002. The Theological and Ethical Writings of Frances Power Cobbe, 1822-1904. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen.

Stone, Alison. 2022. Frances Power Cobbe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stone, Alison, ed. 2022. Frances Power Cobbe: Essential Writings of a Nineteenth-Century Feminist Philosopher. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stone, Alison. 2023. Women Philosophers in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Williamson, Lori. 2005. Power and Protest: Frances Power Cobbe and Victorian Society. London: Rivers Oram Press.

Archival Resources (selected):

Frances Power Cobbe Correspondence, Huntington Library, California, includes letters addressed to Cobbe covering women’s rights, anti-vivisection, morality, and religion.

Her letters with Darwin are online at the Darwin Correspondence Project: https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk

Web Resources (selected):

Dalzell, Sarah. 2025. Frances Power Cobbe – the Forgotten Victorian Feminist. https://womenslibrary.org.uk/2025/02/07/frances-power-cobbe-the-forgotten-victorian-feminist/

Scott, Sarah. 2024. Lessons from a 19th Century Woman Philosopher about Ethics and Public Philosophy. https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/ppr/research/ethics-values-and-policy-initiative/blogs/lessons-from-a-19th-century-woman-philosopher-about-ethics-and-public-philosophy

Simpson, Matthew. 2017. In Defence of Frances Power Cobbe. Voice for Ethical Research at Oxford. https://voiceforethicalresearchatoxford.wordpress.com/2017/08/01/in-defence-of-frances-power-cobbe/

Smith, Cathal Dowd. n.d. Frances Power Cobbe: A Fingal Daughter of Feminism. https://newbridgehouseandfarm.com/frances-power-cobbe-a-fingal-daughter-of-feminism/

Stone, Alison. 2020. Frances Power Cobbe and Nineteenth-Century Moral Philosophy. Blog of the American Philosophical Association. https://blog.apaonline.org/2020/07/01/francis-power-cobbe-and-nineteenth-century-moral-philosophy/

Stone, Alison. 2023. Why We Should Read Frances Power Cobbe as a Philosopher. https://acezekiel.com/2022/08/04/why-we-should-read-frances-power-cobbe-as-a-philosopher-guest-blog-by-alison-stone/

Comment

Your message was sent successfully