Birth

4th century BCE

Death

Unknown

Erinna is remembered for her extraordinary yet fragmentary work, The Distaff, a 300-line lament for her childhood friend Baucis. Writing in an unusual blend of Doric and Aeolic dialect, Erinna transformed private grief and feminine experience into a public poetic voice within the traditionally male domain of epic hexameter. Her surviving verses reveal themes of memory, friendship, and women’s daily life, particularly through imagery of spinning and fate. Celebrated in antiquity alongside Sappho and Homer, Erinna’s rare female voice continues to shape discussions of women, poetry, and identity in classical literature.

Personal Information

Name(s)

Erinna (Ἤριννα)

Date and place of birth

Mid-to-late 4th century BCE (c. 350 BCE); exact birthplace uncertain: ancient sources suggest Lesbos, Teos, Telos, Rhodes, or Tenos

Death and place of death

Unknown; romantic tradition holds that she died at age nineteen

Family

Mother:

Unnamed; referenced in The Distaff

Father:

Not mentioned in ancient sources

Marriage and Family Life

No evidence of marriage or children. Later tradition claims she died unmarried (‘a virgin’) at nineteen. The absence of marital references in her extant poetry has encouraged readings that emphasize the intimacy and emotional centrality of female friendship, particularly with Baucis. She mentions her mother (without naming her) in The Distaff; some readers see this as a reference to herself playing a role in a game with her friend Baucis

Education (Short Version)

Received a thorough education in poetic forms, including Homeric hexameter; possibly self-educated or taught in a domestic setting, as was available to elite Greek women.

Education (Long Version)

Although direct information is lacking, the sophistication of Erinna’s work in hexameter suggests familiarity with epic tradition and access to literary education through family or local institutions. Her use of dialect and form suggests she read and responded to Sappho and Homer. Her education is consistent with the evidence of female literacy and education in fourth-century Teos and other Ionian or Dorian cities.

Religion

Greek polytheism: references to the Fates and underworld figures in her poetry reflect traditional Greek religious imagery.

Transformation(s)

Erinna's poetry emerged from a context in which published female works were rare. This is particularly true of works in the epic meter of Homer, the dactylic hexameter. The death of her childhood friend Baucis inspired The Distaff, her best-known work. Her decision to write in an artificial dialect, a mixed Doric and Aeolic dialect, rather than the epic Ionic norm, marked a self-conscious gendering and regionalization of poetic voice, aligning her with Sappho and local traditions rather than Homeric masculinity. Through her lamentation, she transforms private grief into public poetic legacy, asserting the legitimacy of female experience in a genre dominated by male voices.

Contemporaneous Network(s)

Erinna was later linked to Sappho through dialect, subject matter and perhaps simply by being female. Greek poets such as Asclepiades, Antipater of Sidon, and Meleager place her within prestigious poetic networks. Meleager included her in his ‘Garland’ of famous poets; Antipater of Thessalonica in his list of nine ‘divine-voiced’ women poets. Herodas linked her to Nossis, another female poet, in a comic essay, showing how women poets were sometimes grouped together, either seriously or humorously. Though anachronistic, these linkages show how Erinna was imagined as part of a female poetic lineage.

less

Significance

Works/Agency

Erinna's most famous work is The Distaff (ἡ ’Ηλακάτη), a 300-line lament for her childhood friend Baucis who, it appears from extant fragments of the poem, died shortly after her marriage. About 54 lines survive on papyrus found in 1928. The poem blends themes of mourning, memory, and domestic ritual. The theme of spinning touches traditional female activity and skill, while alluding to the writing of poetry (the spinning of the thread of a poem by the Muses), and the thread of life held by the Fates. Erinna’s reflection on childhood games she played with Baucis provides an important source for a girl’s life in this society. Erinna’s work crossed boundaries with her firm focus on feminine friendship and childhood, presented in a particularly masculine poetic genre, the Homeric epic hexameter.

Her artificial literary dialect shows her control of language, with a Doric-based dialect perhaps reflecting her own, while an overlay of Aeolic forms links her to Sappho (accounting in part for the identification of her in antiquity as Sappho’s contemporary). Her poetic voice blends personal emotion with refined form, asserting a female perspective within a traditionally masculine genre.

Three epigrams are also attributed to her in the Greek Anthology (6.352, 7.710, 7.712), two of which commemorate Baucis; and one refers to a portrait of a woman named Agatharchis. Their authenticity is debated.

Contemporaneous Identifications

Erinna was celebrated in antiquity as a youthful poetic prodigy. She was compared favorably with Homer and Sappho, a mark of profound respect as they were considered the finest hexameter poet and the finest lyric (and female) poet, respectively. Erinna was recognized for her literary refinement despite what was noted in antiquity as a limited output of work. She was remembered primarily as a lamenting voice and a representative of female emotional bonds.

Reputation

Erinna's reputation was high in antiquity. Asclepiades, Leonidas (or Meleager), and two anonymous poets wrote epigrams in her honor (Greek Anthology 7.11-13, 9.190). Antipater of Sidon praised her few verses as inspired and eternally memorable (Greek Anthology 7.713). Antipater of Thessalonica listed her among the nine ‘Earthly Muses,’ whose work gives ‘undying delight’ (Greek Anthology 9.26). Meleager included her in his ‘Garland’ of poets, calling her work ‘sweet saffron’ and ‘of maidenly color’ (Greek Anthology 4.1.12). The Suda, centuries later, synthesized legendary details about her, highlighting both her poetic gifts and tragic early death. In modern scholarship, she is studied as a rare example of a female voice from early Greek poetry. Debate exists over the authenticity of her works and even her gender, with West (1977) arguing Erinna was a pseudonym for a male poet—a claim widely challenged.

In antiquity Erinna was the subject of more than one statue, testament to the ongoing positive reception of her work. A description of a statue that was in the public bath and gymnasium complex in Constantinople appears in the Greek Anthology (2.1.108–10) and is evidence of her fame into the sixth century CE. Tatian claimed that the sculptor Naucydes made a statue of her, though the incompatibility of Naucydes’ dates with Erinna’s suggests Tatian has misidentified the sculptor.

Legacy and Influence

Erinna's legacy persists in scholarship on ancient female poets. She appears in anthologies of women’s literature, feminist literary studies, and works on Hellenistic poetry. Her name and The Distaff remain touchstones in discussions of women's voice, loss, and literary craft in antiquity.

A nineteenth century statue of her by Henry Leifchild (1860), now at Royal Holloway, University of London, reflects a Victorian-era romanticized image of her; a painting by Simeon Solomon from the same time, ‘Sappho and Erinna in a Garden at Mytilene’ (1864: Tate Britain) pictures her being embraced by Sappho.

For a creative modern literary response to Erinna’s work, see Marguerite Johnson’s ‘Memories of Erinna (After Erinna).’

less

Controversies

Controversy

Multiple controversies surround Erinna. These include the authenticity of the epigrams attributed to her; the accuracy of the tradition that she died at 19; and even her very identity. West (1977) argued The Distaff was too polished for a teenage girl to have written and may have been written by a male in her voice. West reflects a prejudice against female authors also seen in antiquity, where Athenaeus questioned whether a woman wrote the work attributed to her (7.283d). This has been contested by scholars such as Pomeroy (1978) and Snyder (1991), who maintain that women of the era could and did receive literary education and compose sophisticated verse.

Some argue the epigrams attributed to her were later compositions inspired by The Distaff and this remains a possibility. However, the editors of the Greek Anthology (and later the Suda) accepted her authorship of epigrams. Her dialect, a mix of Doric and Aeolic, has also fuelled debate about her regional origin and poetic intent.

New and Unfolding Information and/or Interpretations

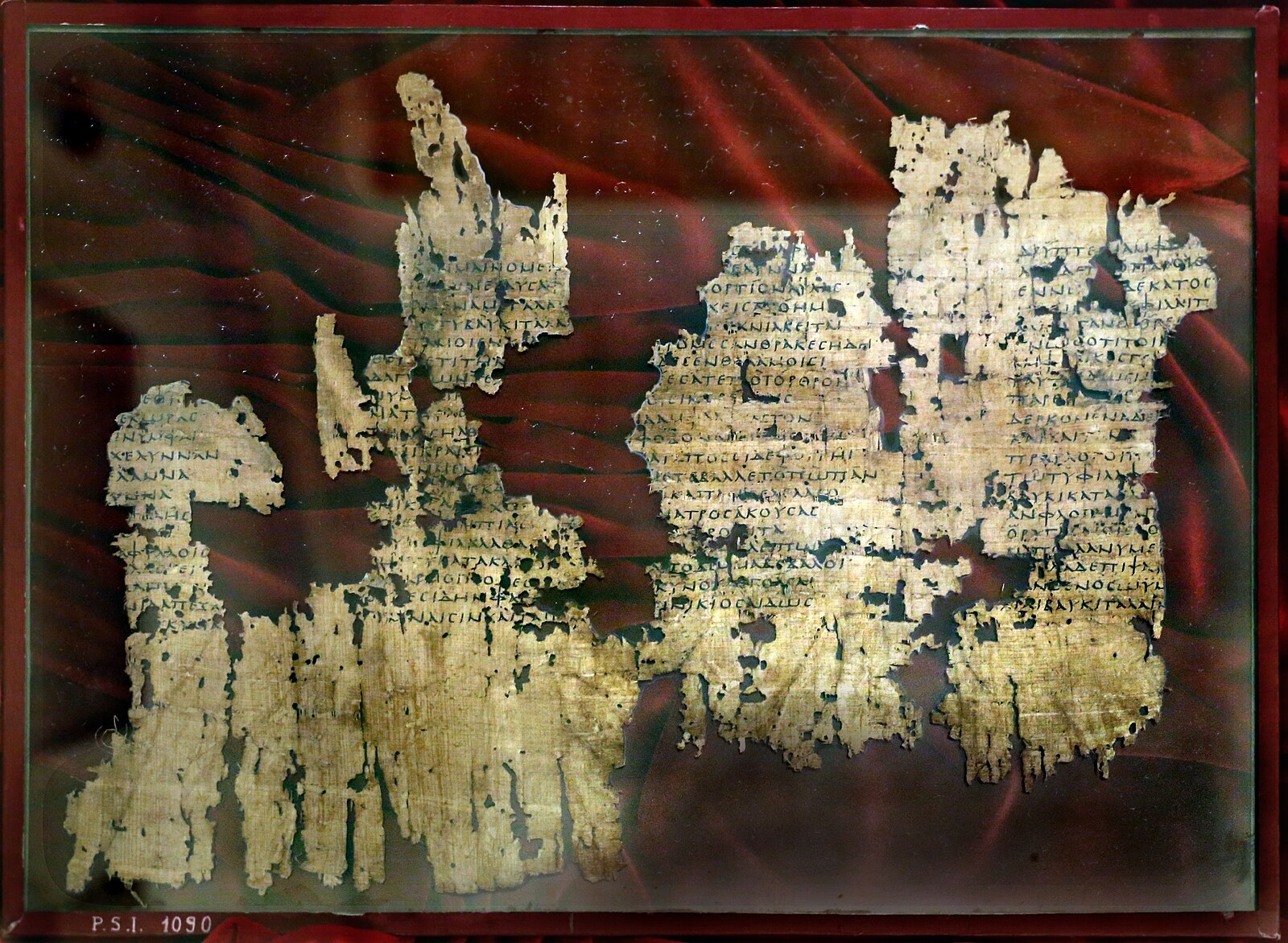

The 1928 discovery of a partial copy of The Distaff on papyrus transformed knowledge of Erinna’s work. Before this, only brief quotations and the three epigrams in the Greek Anthology had survived in her name. The papyrus partially preserved about 54 lines of The Distaff. Although fragmentary in places, this text confirms the poem's quality and justifies the ancient praise of Erinna’s work. An additional piece of the same papyrus roll has recently been identified by Gasperini (2023), giving us what appears to be an additional small fragment of The Distaff.

Further debates have emerged over her dialect (a deliberate mix of Doric and Aeolic) and genre. Some newer studies consider Erinna as a precursor to Alexandrian literary aesthetics and explore her use of female-coded imagery (e.g., weaving) as both metaphor and resistance.

less

Bibliography

Sources Primary (selected):

- The Greek Anthology 6.352, 7.710, 7.712 (Erinna’s epigram fragments); 2.1.108–10, 4.1, 7.11–13, 7.713, 9.26, 9.190, 11.322 (reception of Erinna’s work).

- Papyrus: PSI 9.1090 (fragment of The Distaff): https://psi-online.it/documents/psi;9;1090

- Stobaeus, Anthology 4.50a.14 and 4.51.4 (fragments of The Distaff)

- Athenaeus, The Learned Banqueters 7.283d (fragment of The Distaff)

- Suda, Eta,521(Adler) (biography)

- Tatian, Address to the Greeks 33 (statue of Erinna)

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History 34.57 (reference to her poetry)

Archival Resources (selected):

- Gasperini, I. (2023). ‘P. Amst. inv. 66 (S/ZN 55): un altro frammento della Conocchia di Erinna?’ Aegyptus 103: 17–47.

- Johnson M. (2014). ‘Memories of Erinna (After Erinna).’ Arion 22.1: 175–78. https://www.jstor.org/stable/arion.22.1.0175

- Lloyd-Jones, H. and P. Parsons (eds) (1983). ‘Erinna.’ Supplementum Hellenisticum. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter,186–93, no. 401–6. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110837766.186

- Levin, D. N. (1962). ‘Quaestiones Erinneanae.’ Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 66: 193–204. https://www.jstor.org/stable/310740

- Neri, C. (2003). Erinna: testimonianze e frammenti. Bologna: Pàtron Editore.

- Plant, I. M. (2004). Women Writers of Ancient Greek and Rome: An Anthology. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, pp. 48–52. (Google Books link).

- Pomeroy, S.B. (1978). ‘Supplementary Notes on Erinna.’ Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 32: 17–22. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20185555

- Snyder, J. M. (1991). The Woman and the Lyre: Women Writers in Classical Greece and Rome. Carbondale: SIU Press, 86–98.

- West, M.L. (1977). ‘Erinna.’ Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 25: 95–119. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20181346

Web Resources (selected):

- Attalus: https://www.attalus.org/poetry/erinna.html

- Perseus Digital Library: https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/

- Diotíma: https://diotima-doctafemina.org/

Issues with the Sources

The papyrus evidence is fragmentary. Much of the biographical tradition derives from later sources (such as the Suda), which conflates poetic persona with historical fact. Attribution of epigrams remains disputed. Ancient and modern scholars differ on Erinna's identity, authorship, and education.

- Images

- Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana manuscripts: Oxyrhynchus fragment of The Distaff, about 190 CE (psi IX 1090).jpg: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erinna#/media/File:Ossirinco,_frammento_di_papiro_con_alakata_(conocchia)_di_erinna,_190_dc_ca._(psi_IX_1090).jpg

- ‘Sappho and Erinna in a Garden at Mytilene’ by Simeon Solomon (1864): Tate Britain: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erinna#/media/File:Sappho_and_Erinna_in_a_Garden_at_Mytilene.jpg

- Statue: ‘Erinna’ by Henry Leifchild (1860): Royal Holloway, University of London: https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/erinna-251642

Comment

Your message was sent successfully