Birth

1510

Death

October 1562

Religion

Protestant, Roman Catholic, UnknownElizabeth Pickering was the first named woman printer in England whose books still survive and the first Englishwoman to publish books under her maiden name, as well as the first woman printer in London.

Personal Information

Name(s)

Elizabeth Pickering

Date and place of birth

Born c. 1510 (London?)

Date and place of death

Pickering died in October 1562. Her funeral was held at St. Margaret Lothbury in the center of London and her body buried in the Church of St. Dunstans-in-the-West in Fleet Street, the area still associated with printing, in the City of London.

Family

Parentage is unknown.

Marriage and Family Life

Elizabeth Pickering had four husbands. Her first husband is recorded only as “Jackson” (death date unknown) by whom she had two daughters, Luce (Lucy) Jackson and Elizabeth Jackson. Both daughters lived to adulthood and later married. Sometime after September 29, 1536, Pickering married the printer Robert Redman (d. October 1540) who had two daughters from a previous marriage, Mildred Redman who married Edward Hanbury in February 1544 and Katherine Redman, who died between 1541 and 1544. A third child, Alice Redman, seems to have been Redman’s daughter with Elizabeth; she was still underage in 1556. Pickering married her third husband, William Cholmeley (d. 1546) in 1541, a wealthy lawyer; there is mention in the Church Warden’s account in 1542 of the burial of “Wm Cholmeley’s son,” though we do not know whether the mother was Elizabeth or a previous wife. Finally, she married her fourth husband, Randolph Cholmeley, a relative of William, who died in 1563. They had no children.

Education

Elizabeth Pickering was literate, one might surmise, though not all printers were, and a number of books she published survive though these were reprints of works printed by her second husband, Robert Redman. She seems to have been an able manager and astute businesswoman in deciding which titles to reprint.

Religion

It is unknown whether Pickering was Roman Catholic or Protestant. The Reformation occurred in her lifetime, which meant a major transformation in religious practice in England. Her first publication in 1540 was John Standish’s Treatise Against Bankes, which describes the burning of the Protestant martyr Robert Bankes at Smithfield, a work that was answered by the Reformer Miles Coverdale. Originally Catholic, Standish (d. 1570) trained for the priesthood but himself became a Protestant later in the 1540s. This book was a reprint of the volume published by her husband, Robert Redman, and may simply have been the reprinting of a bestseller, not to be interpreted as a reliable guide to Elizabeth’s own religious belief. Redman, Elizabeth’s second husband, may have had Protestant sympathies as among his publications are works by the reformers William Hardy and John Frith, though again these publications may have been motivated by good business practice rather than religion. Pickering did not reprint any of the books published by her husband that might have been deemed controversial in 1540, printing mainly law books and books on health (see Archival Resources).

less

Significance

Works/Agency

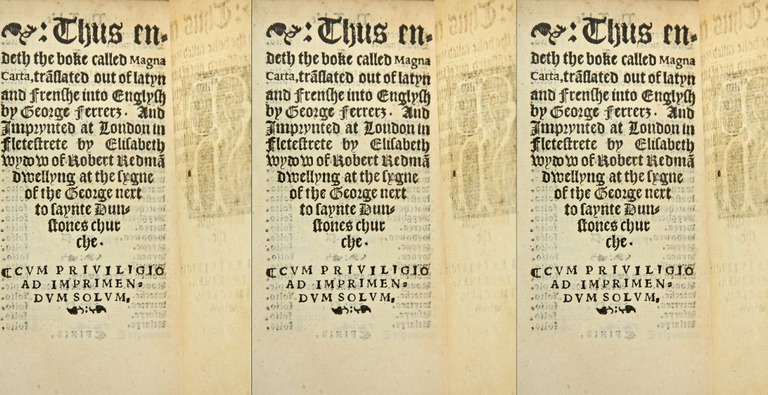

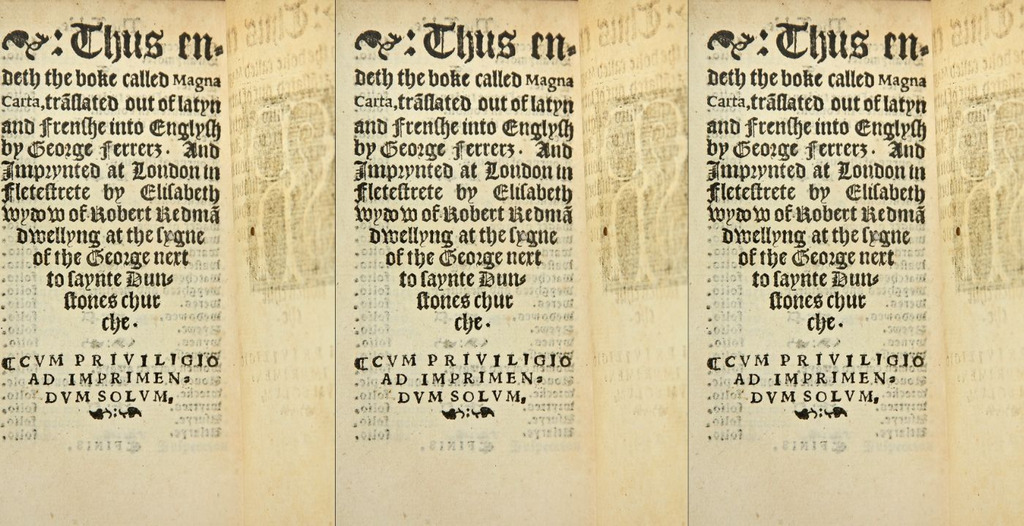

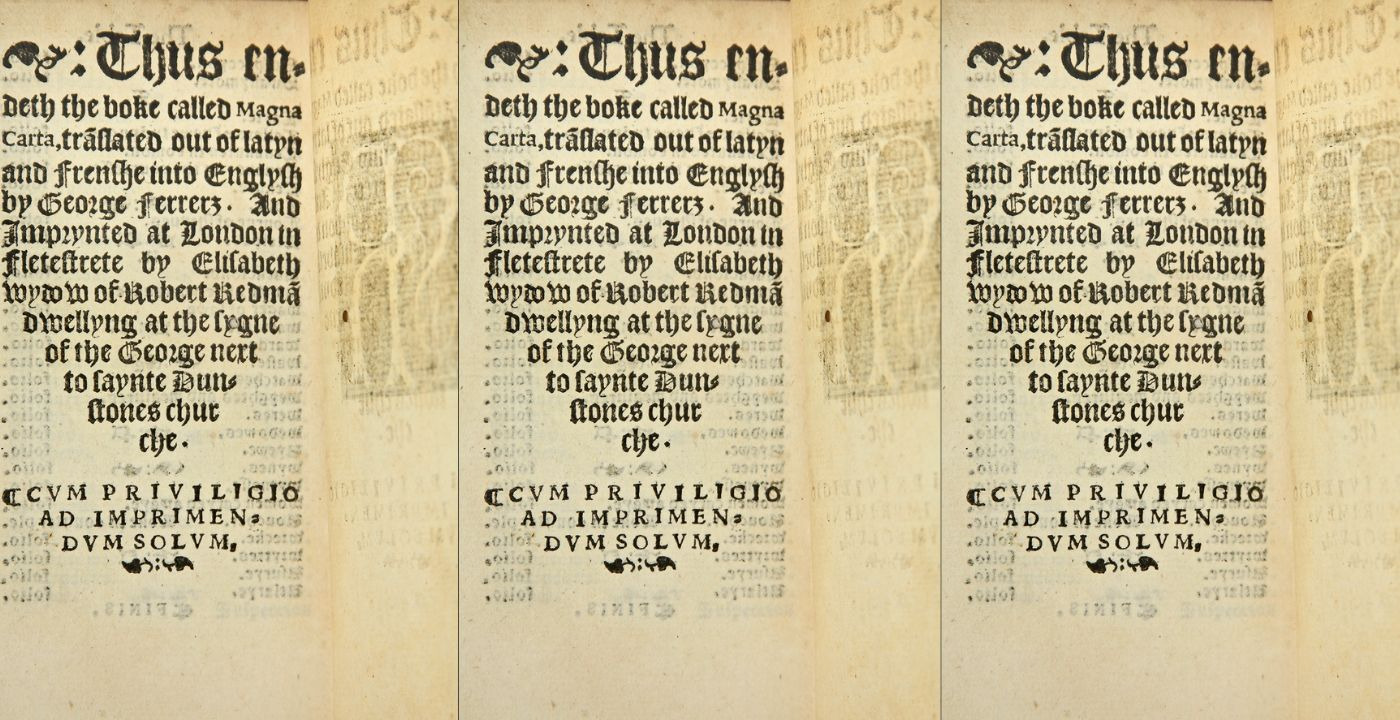

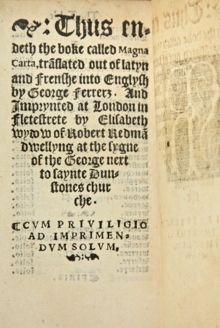

Pickering is the first named woman printer in England whose books still survive and the first Englishwoman to publish books under her maiden name, as well as the first woman printer in London. After the death of her second husband, the printer Robert Redman, Elizabeth continued to run his shop, publishing at least twelve books, according to the Short Title Catalogue (others are cautiously attributed to her), in which she describes herself variously as “Elysabeth late wife vnto Robert Redman,” “Elisabeth widow of Robert Redman,” and “Elysabeth Pykeryng late wife to Robert Redman.” The name “Pykeryng” occurs in several, perhaps later books printed by Elizabeth (many of her books are undated). In The Maner of Kepyng a Courte Baron, the colophon reads “by me Elisabeth Pykerynge widow of Robert Redman,” while in the Offyce of Shyreffes, the colophon states the book was printed “by me Elysabeth Pykerynge wydo to Robert Redman dwellynge at the synge [sic] of the G[e]orge nexte to saynt Dunstones Churche.” The emphatic “by me,” used conventionally by male printers in colophons by this era, is used only by Elizabeth when she gives her maiden name or when she identifies herself by her first name only as “Elysabeth late wife to Robert Redman,” she does in the Abregement of the Statutes (1541?).

As a widow, Elizabeth successfully ran the print shop, but once she married a third time, outside the printers’ guild, she sold it to the printer William Middleton who continued to publish many of the same law books that Redman and Pickering had printed previously. [See Transformation.]

Reputation

Pickering was rediscovered in the twentieth century when feminist scholars became interested in women’s work, especially in Pickering’s case, in the making and printing of books by women during the Tudor period.

Transformation

While male printers were busily engaged in commercial promotion along with production, women worked alongside fathers, husbands, brothers, and sons to print books in the shop. Being married to a member of a guild or mystery (a medieval association of craftsmen or merchants) meant a woman could work beside her husband in a business; widows could continue in the trade after the death of their husbands. Robert Redman, Pickering’s second husband, mainly printed law books in a shop formerly owned by Richard Pynson, one of the successors of William Caxton, who introduced printing from the Continent into England in the late fifteenth century. As the wife, then widow, of Robert Redman, Pickering was able to print books after Redman’s death. Widows customarily kept their husband’s printer’s mark or device (a form of trademark) that usually appeared on the final page of books and continued to use their husband’s name, adding “widow of.” There is some evidence Pickering began printing even before her husband’s death: the British Library copy of The Treasure of Poore Men has the colophon: “Imprinted by me Robert Redman 24 Jan 1539,” but the printer’s initials ‘E.R.’ are presumed to stand for his wife, Elizabeth. This is a variant of Redman’s original printer’s device or mark. After a productive career of only two years as a printer, Pickering married a third husband, who was outside the guild system, so Pickering was forced to sell the business. Her third husband was a wealthy lawyer, William Cholmeley, and the printing house passed to William Middleton, who then took over the sign of the George in Fleet Street. Kreps notes that William Cholmeley purchased his freedom as a stationer on May 31, 1541, presumably to enable ready transfer of the print shop to Middleton. William Cholmeley drafted an unsuccessful early charter of incorporation for the yet-to-be-formed Stationers’ Company. Peter Blayney speculates that perhaps the Stationers’ Company was originally Elizabeth’s idea. After Cholmeley’s death in 1546, Elizabeth married a fourth time to Randolph (also Ranulf, Ralph) Cholmeley, another lawyer and a kinsman of William. In 1554, Ranulf Cholmeley became Recorder of London, a powerful position second only to the Lord Mayor and the Court of Aldermen, and was able to push through the first successful draft of the incorporation of the Company of Stationers; it received a royal charter in 1557. The fact that two men named Cholmeley (who were related) married Elizabeth in succession and that both were intent on forming the Stationers’ Company, which gave its members a virtual monopoly over printing in England, seems to suggest that Elizabeth influenced that decision.

Legacy and Influence

Only two books printed by Elizabeth Pickering are dated, one in 1540, the other in 1541. Eight further books survive but are undated. In three further books attributed to Pickering, the colophon identifies the printer as Robert Redman, but other evidence suggests these were printed after his death. The number of books attributed to Pickering’s press needs further study.

Networks

Through her marriages and her two-year stint as a printer, Elizabeth made some powerful connections. The will of her last husband suggests something of the circles in which Elizabeth travelled. They apparently knew William Roper, the son-in-law of Sir Thomas More, Richard Tottel, the publisher (and editor) of the poetry of Sir Thomas Wyatt who also gained an important patent on the publication of law books in 1553, and several lord mayors of London, Thomas Leigh, Thomas Offley, and William Chester.

less

Controversies

Controversy

Kreps has done the most helpful research on Pickering, though many questions about her remain.

Feminism/Social Activism

Though “feminism” had not yet been coined or formally considered in this period, the evolution of Pickering’s printer’s marks from “widow of” to the use of her maiden name seems to point to an emerging sense of self, separate from that of her dead husband, and the beginnings of a separate identity, marking the books she printed as her own.

less

Bibliography

Primary

A Short-Title Catalogue of Books printed in England, Scotland, and Ireland and of English Books printed abroad 1475-1640. Second edition. Revised and enlarged. 3 vols. Edited by A. W. Pollard , G. R. Redgrave , W. A. Jackson , F. S. Ferguson , Katharine F. Pantzer. London: Bibliographical Society, 1976—1991.

Blayney, Peter. The Stationers’ Company before the Charter, 1403—

- 1557. London: Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers, 2003.

Driver, Martha. “‘By Me Elysabeth Pykeryng’: Women and Book Production in the Early Tudor Period.” Manuscripts and Printed Books in Europe 1350—1550, ed. by Emma Cayley and Susan Powell. Liverpool University Press, 2013, pp. 115—120.

Driver, Martha. "Women Printers and the Page, 1477—1541." Gutenberg-Jahrbuch (1998): 139-153.

Kreps, Barbara. “Elizabeth Pickering: The First Woman to Print Law Books in England and Relations Within the Community of Tudor London’s Printers and Lawyers. Renaissance Quarterly 56, 4 (Winter 2003): 1053—1058.

Archival resources.

A boke of the propertyes of herbes the whiche is called an Herbal. N.d. STC 13175.7

A lytle treatyse composed by Iohn Sta[n]dysshe ... againste the [pro]testacion of Robert barnes at ye time of his dethe. 1540. STC 23210.

Abregement of the statutes xxiii Henry viii. N.d. STC 9535.

Abregement of the statutes of [sic] made xxxii Henry viii. N.d. STC 9543.

Myrrour or Glasse of Helth. N.d. STC 18219.

Returna Breuium. 6 May 1541. STC 20901.

The abregement of the statutes of Anno xxxj Henrici viij. N.d;m STC 9542.3

The Great Charter called in latyn Magna Carta. N.d. STC 9275.

The Maner of Kepynge a courte baron and a Lete. N.d. STC 7716.

The newe Boke of Iustices of peas made by Anthony Fitzherbard iudge. 29 Dec. 1540; colophon 1541. STC 10970.

The office of sh[y]reffes, bailliffes of liberties, escheatours co[n]stables and coroners. N.d. STC 10985.

Paruus libellus continens formas multarum rerum [Carta Feodi]. 1541. STC 15584.7.

The seynge of urynes of all the couloures that urynes be of. N.d. STC 22155.

Web resources

Gillespie, Alexandra. “Elisabeth Pickering,”en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elisabeth Pickering

Gillespie, Alexandra .“Elisabeth Pickering (c.1510–1562)” in “Redman, Robert (d. 1540)." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/69150.(Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

Comment

Your message was sent successfully