Birth

3rd century BCE

Death

Unknown

Corinna was an ancient Greek lyric poet from Tanagra in Boeotia, likely active in the 3rd century BCE. She composed mythological narrative poetry in Boeotian dialect for girls' choruses, transforming traditional myths by centering female voices and local perspectives. Her works, collected in five books titled "Weroia" (Tales), retold Panhellenic myths with emphasis on female agency and Boeotian heroines. Corinna strategically positioned herself within the male-dominated poetic tradition, using irony and invented vocabulary to claim authority for women's storytelling. Her innovative approach to localizing myth and integrating female experiences into public festival poetry established her as a significant voice in ancient Greek literature, influencing Roman poets and earning recognition in poetic canons throughout antiquity.

Personal Information

Name(s)

Corinna (or Korinna); Κόριννα

Date and place of birth

Traditionally said to have flourished in the 5th century BCE, but modern scholars place her more reliably in the early to mid-3rd century BCE. She was from Tanagra in Boeotia, central Greece

Date and place of death

Unknown; she probably lived her life in Tanagra, Boeotia

Family

Mother: Prokratia (Suda Kappa 2087)

Father: Acheloodoros (Suda Kappa 2087)

Marriage and Family Life

No evidence survives regarding a husband or children. Ancient sources emphasize her literary and poetic role, not familial status.

Education (short version)

Educated in the poetic and musical traditions of Boeotia, in a setting that supported choral performance and the transmission of myth.

Education (longer version)

Corinna’s command of mythological narrative, complex dialect, and choral forms suggests advanced education, either in a formal context or through elite female training in the Boeotian musical tradition. She was trained in the performance of partheneia (songs for girls’ choruses) and may have learned poetic craft from oral tradition and from engagement with canonical poets such as Pindar and Hesiod. The Suda names a Boeotian female lyric poet, Myrtis, as her teacher, and she herself refers to both Myrtis and Pindar (who were both also Boeotian), situating herself within a Boeotian poetic lineage.

Religion

Greek polytheism. Her poems include invocations to Terpsichore (Muse of dance and choral song) and the other Muses, as well as references to deities such as Zeus, Poseidon, Apollo, Hermes, Aphrodite and Eros. They were composed for performance at important Boeotian religious festivals such as the Mouseia (Thespiae) and the Daedala (Plataea).

Transformation(s)

Corinna transformed the performance of myth by integrating female voices and local perspectives into public festival poetry. She adopted and refashioned the lyric tradition of Boeotia to foreground local heroines alongside heroes, using a distinctive Boeotian dialect and placing her poetic authority in the collective voice of girls’ choruses. Her poetic persona oscillates between individual voice and communal identity, often using irony and invented vocabulary (e.g., ligourokōtilus, ‘gossipy-clear’) to claim a place for women in myth-making and history. Her decision to retell myth from a local and gendered point of view was a quiet but powerful act of cultural authorship.

Contemporaneous Network(s)

Corinna was imagined in antiquity to be a contemporary and rival of Pindar, whom she is said to have defeated in poetic competitions. She also criticized Myrtis, another Boeotian female poet, in a surviving fragment (664a). These references indicate her literary awareness of, and strategic positioning within, a lineage of Boeotian poets. Although their historical encounters are unlikely, these references allowed Corinna to align herself with, and critique, authoritative male voices. According to Heath (2017), she playfully engages with the stereotype of women's storytelling to recast it as authoritative mythopoesis.

less

Significance

Works/Agency

Corinna composed narrative lyric poetry, especially mythological odes, in a choral style for girls’ choirs. The Suda says she also composed epigrams, but these have not survived. Her works were collected into five books, titled Weroia (Tales). She wrote in a literary Boeotian dialect, using both epic and lyric forms. Her poems retell myths with local focus and often center on female figures: examples include the daughters of Asopus (654a.ii), the musical contest between Helicon and Cithaeron (654a.i), and allusions to Athena, Rhea, and the eponymous nymph Thespia. She innovates by localizing Panhellenic myths, emphasizing female agency, and integrating aetiology into performance contexts. Her invented vocabulary (e.g., ligourokōtilus) and programmatic statements (655) highlight her self-awareness as a myth-maker.

Contemporaneous Identifications

Identified by the Suda as the pupil of the lyric poet Myrtis. She mentions Myrtis in one fragment. Her poetry, written for performance by girls of Tanagra, positioned her as a cultural educator. Though later tradition dates her to the 5th century BCE, linguistic and metrical analysis places her more securely in the 3rd century BCE.

Reputation

Highly regarded in antiquity, Corinna was included in poetic canons by Antipater of Thessalonica (Greek Anthology 9.26) and Clement of Alexandria (Strom. 4.19). She was also mentioned admiringly by Pausanias (Description of Greece 9.22.3), Aelian (Historical Miscellany 13.25), and Plutarch (4.347f–348a). Pausanias describes a painting of her in the gymnasium at Tanagra and a conspicuous tomb in her honor in the center of the city. Tatian says that there was a statue to her, made by the fourth-century Athenian sculptor Silanion (Address to the Greeks 33). Roman poets like Propertius and Statius allude to her, with Propertius suggesting that his girlfriend (whom he names elsewhere Cynthia) read Corinna and measured her own poetry against hers (2.3.21–2); Statius speaks of the skill his father displayed in explaining ‘slim Corinna’s mysteries’ (Silv. 5.3.158). Corinna was anthologized and commented upon into late antiquity. Though overlooked in some modern narratives of Greek poetry, feminist scholarship has reassessed her work as both sophisticated and subversive. Larmour (2005) and Heath (2017) in particular emphasize her ironic engagement with epic and epinician traditions.

Legacy and Influence

Corinna’s work exemplifies female authorship within the public poetic sphere and has become central to discussions of gender and voice in ancient Greek literature. Her legacy includes influence on Roman poets and continued recognition in modern scholarship. Ovid chose Corinna as the pseudonym of his paramour in the Amores. Commentators from the Renaissance to the 21st century have wrestled with her dating, authenticity, and literary value. Her method of adapting myths for local, often female, audiences serves as a model for literary localization and feminist reinterpretation of tradition. Today, she appears in university syllabi, feminist literary histories, and translations of women poets of antiquity.

less

Controversies

Controversy

A major controversy surrounds Corinna’s date. Ancient sources place her in the 5th century BCE as Pindar’s contemporary and competitor, but linguistic and metrical analysis (West 1970; Page 1953) strongly favours a 3rd-century BCE date. The anecdotal tradition of poetic victories over Pindar is now widely regarded as a retrojection. Another debate involves the nature of her audience: some have claimed her poems were exclusively for female performance (Rayor 1993), while others (Heath 2017; Larmour 2005) argue for mixed audiences. Questions also persist about her tone—is it ironic, serious, didactic, or all at once? Heath emphasizes her strategic use of a ‘chattering’ voice to reclaim women’s storytelling as authoritative.

New and Unfolding Information and/or Interpretations

Recent scholarship emphasizes Corinna’s mythological innovation, her strategic use of dialect, and her engagement with earlier Greek poets. Heath (2017) interprets her poetic persona as deliberately negotiating female voice and authority, especially through ironic self-characterization. Larmour (2005) sees her work as a reaction to, and subtle subversion of, Pindar’s Panhellenic epinician mode. Scholars now explore the performative dimensions of her poetry, its integration into civic festivals (e.g. Daedala), and its role in the cultural education of young women. Corinna's emphasis on female figures, community identity, and oral traditions suggests a broader cultural role than once assumed.

less

Bibliography

Sources Primary (selected):

- Fragments in PMG (654–688), especially 654a.i–iii, 655, 664a–b, 667, 674

- Plutarch, On the Glory of Athens 347f–348a = on Corinna advising Pindar

- Pausanias, Description of Greece 9.22.3

- Aelian, Varia Historia 13.25

- Suda, entry on Korinna (K 2087)

Secondary (selected):

- Heath, J. (2017). ‘Corinna’s ‘Old Wives’ Tales.’’ Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 109: 83–130.

- Larmour, D. H. J. (2005). ‘Corinna’s Poetic Metis and the Epinikian Tradition,’ in Ellen Greene (ed.), Women Poets in Ancient Greece and Rome, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 25–34.

- Page, D.L. (1953). Corinna. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 359–58.

- Plant, I. M. (2025). ‘Women Creating History,’ in E. Hauser and H. Taylor (eds), Women Creating Classics: A Retrospective, London: Bloomsbury Academic 13-22.

- Plant, I. M. (2004). Women Writers of Ancient Greece and Rome. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, pp. 92–98.

- Rayor, D. (1993). ‘Korinna: Gender and the Narrative Tradition,’ Arethusa 26: 219–31.

- West, M.L. (1970). ’Corinna,’ Classical Quarterly 20 (2): 277–87.

Archival and Web Resources:

- Perseus Digital Library: https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/

Issues with the Sources

Corinna’s poems survive only in fragments. Attribution of some material is debated. Ancient anecdotes about her competition with Pindar are fictional. Later sources (e.g., Pausanias, Plutarch) reflect retrospective idealization. Linguistic evidence remains the most dependable for dating her corpus.

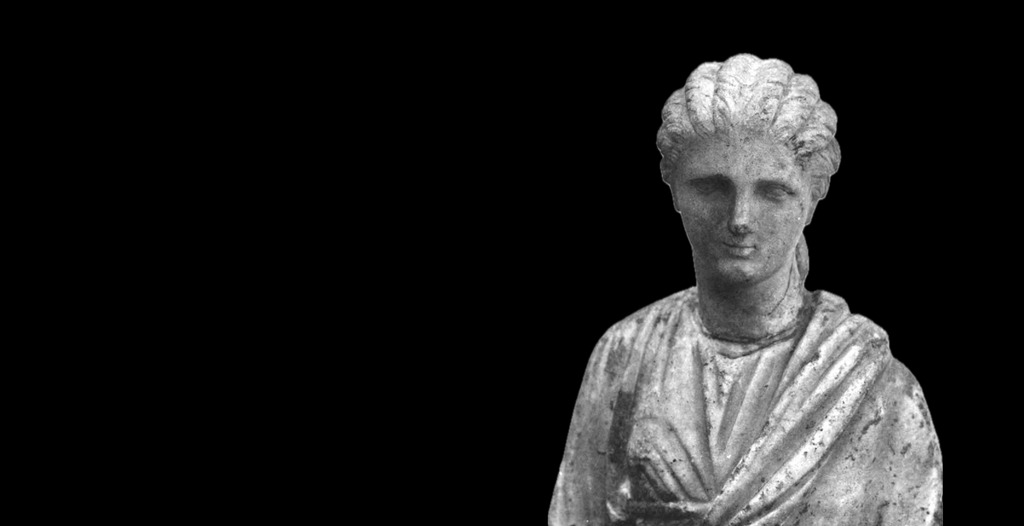

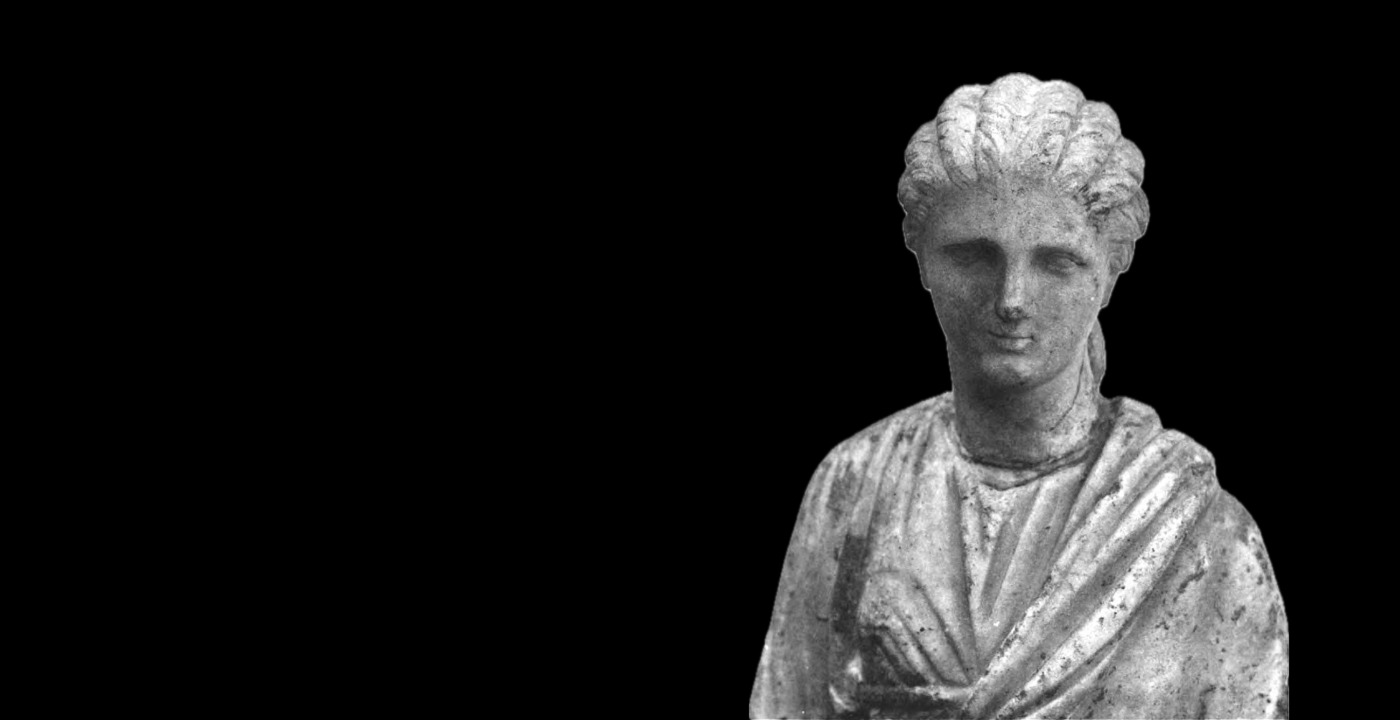

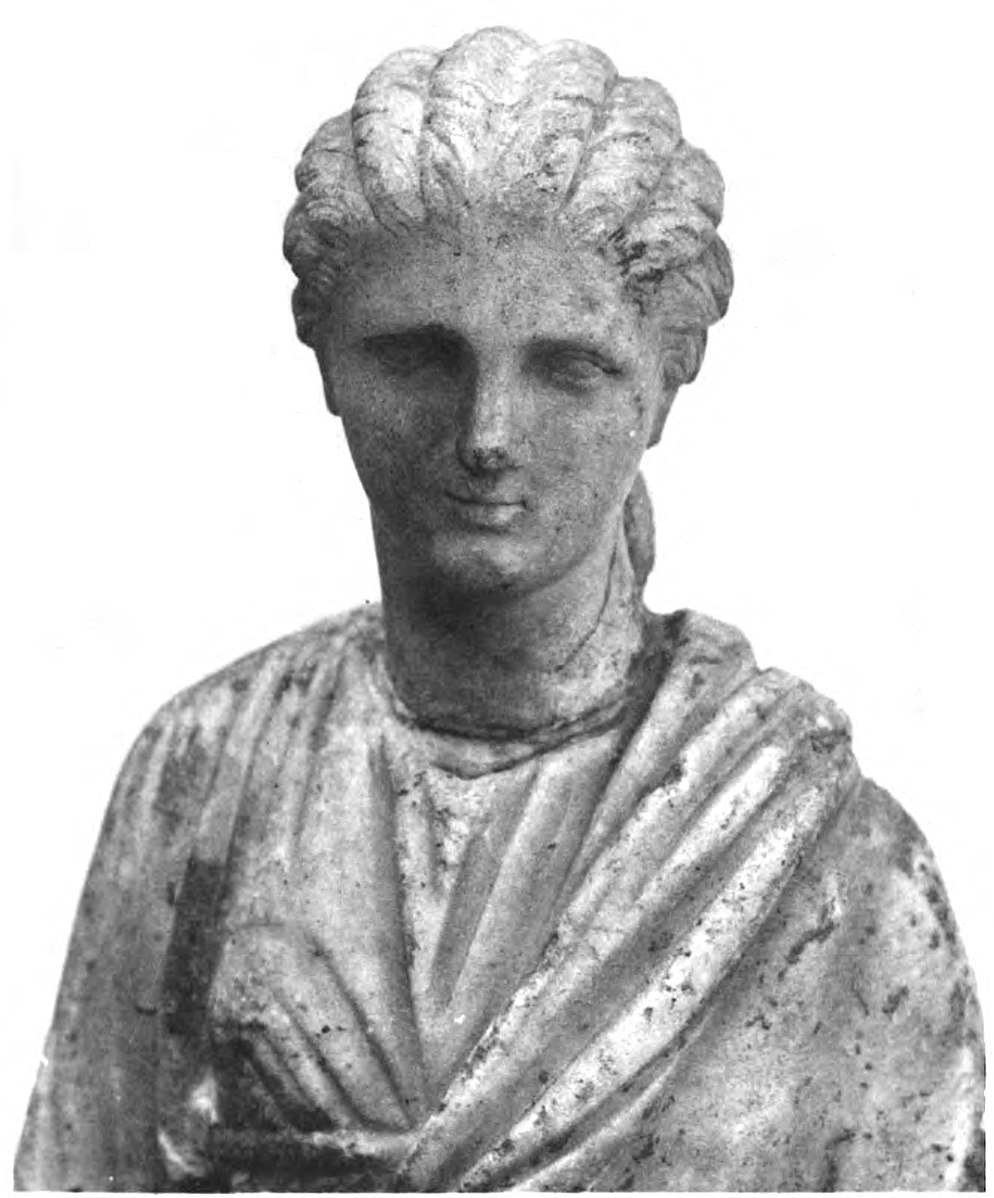

- Images

Statuette of Corinna. Campiègne, Musée Antoine Vivenel. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Statue_of_Corinna_(Revue_arch%C3%A9ologique_1900_36,II).jpg

Attestations of Ancient Images of Corinna

- Pausanias, Description of Greece 9.22.3:

A painting of Corinna in the public gymnasium in Tanagra; she is wearing a fillet (ribbon) of victory on her head, believed to commemorate her poetic victory over Pindar.

- Tatian, Address to the Greeks 33:

Tatian tells us that there was a statue of Corinna by Silanion, an Athenian sculptor who worked in bronze. He is thought to have been most active around 360–320 BCE. Hence Tatian’s attribution of the statue to Silanion is probably an error.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully