Birth

1465

Death

1558

Venetian philosopher, orator, and poet Cassandra Fedele is known to have been active during the 1480s and 1490s when she was in her teens to thirties, and again in 1556 around age ninety. For over 500 years, her reputation has encompassed numerous personas: from child prodigy and aspiring scholar to chaste virgin and living muse; from famous woman and ornament of the State to platonic 'daughter'; from unmarried woman supporting herself to happily married wife to grieving widow. She has been cast as an elderly honored sage, a Venetian and national cultural heroine, and ultimately a feminist icon.

Personal Information

Name(s)

Cassandra Fedele (Fidel, Fidelis, Fedel); Cassandra Mapello (i); and Cassandra Fedele-Mapello (i). The name also appears as Cassandra Fedel quondam Angelo; Cassandra da Ca’ Fideli; Madonna Cassandra; and Cassandra Mapello, relicta di Gianmaria, in contemporary documents.

Date and Place of Birth

ca. 1465, Parish of Santa Marina, Venice

Date and Place of Death

March 24, 1558, Ospedale de le Donzelle of the Monastery of San Domenico di Castello, Venice.

Family

Father:

Angelo Fedele (Fedel, Fidel, Fidelis, ca. 1440 – ca. 1517)

The Fedele family was of Lombard origin. Their name, meaning faithful, was said to have been conferred by the Visconti for their loyalty. Driven out of Milan by internecine warfare, Cassandra’s ancestors eventually reestablished themselves in Venice where they were ranked as Venetian cittadini originari. Generations of learned physicians, lawyers, and high administrators from the Fedele family served the Venetian Republic and the Church. Cassandra’s father, Angelo Fedele (Fedel, Fidel, Fidelis), ca. 1440 – ca. 1517, was the eldest son of the learned physician egregio magister fisico Zuan Fedel (Iohannis, Giovanni) and his wife, Maria. They lived in Calle de la Testa in the Venetian parish of Santa Marina. Documents show the Fedeles had ample means. They received income from farms they owned on the Venetian mainland near Piove di Sacco, Noale, Moniego di Noale, and near Treviso. Although Angelo’s occupation is not known (his brothers Agostino and Francesco were physicians), he probably did not have remunerative employment but was in charge of managing the family’s investments. Angelo’s purchase of a book of Cicero’s letters in February 1485 (more Veneto) is recorded in the register of Venetian bookseller Francesco de’ Madiis. Angelo was admitted as a member of the Scuola Grande di San Marco in 1491. Scholars, including King, Robin, and Ross, have suggested that Angelo sought to use his exceptionally gifted daughter to amass cultural capital in Humanist circles, but there is no way to verify this contention. He was married at least three times. Angelo died around 1517.

Mother:

Chiara Trevisan de la Seda (Clara Trevisan [Trivixan] a Serico), ca. 1440 – 1495.

Giacomo Filippo Tomasini, author of the first Vita, 1636, citing Cassandra’s grand-nephew Paolo Leone’s (lost) memoir, wrote, “her mother was said to be Barbara from the Venetian Leone family.” In Tomasini’s condensed profile of her in Elogia, 1644, he repeated Barbara’s name as Cassandra’s mother. Ever since, this name has been incorrectly asserted as the mother. There is no archival trace of “Barbara Leone,” a name that may have been invented by Paolo Leone. Because Cassandra never named her parents in her (known) writings, many writers have assumed that her mother died early or was not present and influential in her life. Cassandra’s actual mother and other female family members were long present and consequential in Cassandra’s life.

Documents and Fedele and Trevisan de la Seda family tree diagrams in the archives of the monastery of Spirito Santo di Venezia clearly show that Chiara (Clara) Trevisan de la Seda was Cassandra’s and her sisters’ mother. Chiara was a daughter of Venetian citizens Ursa and Nicolo Trevisan de la Seda of the parish of San Giovanni Grisostomo. Chiara’s siblings were Zuane (Giovanni, Ioannis) Trevisan de la Seda (he was the husband of Angelo Fedele’s sister Bianca); Domenico; and Lucrezia (Lamberto, the mother of Bertuccio Lamberto). On March 28, 1463, Angelo Fedele received Chiara’s dowry of 500 gold ducats from her brother, Zuane. Chiara was probably Angelo’s second wife. They lived in the multi-generational family's casa da stazio consisting of two houses, a riva, garden, and a well, located in Calle de la Testa, in the parish of Santa Marina. Angelo and Chiara had at least five daughters together. Gianantonio Zabarino’s poem to Cassandra, quoted by Tomasini 1636, p. 20, contains a previously unnoticed reference to her. Chiara died in 1495, when Casandra was thirty. Benedetto Silvio Costanzo sent a 120-line elegy consoling her upon the death of her mother.

Siblings:

Alessandro Fedele, Cassandra’s older half-brother, was the son of Angelo and his first wife.

Cassandra and her sisters Cristina (Fedele), Filippa (Roi), Maddalena (Fedele), Maria (Venanzio), Polissena (de’ Franceschi), and Elena (Suor Rifugio at San Daniele) were the daughters of Chiara Trevisan de la Seda Fedele.

Husband:

Gianmaria Mapello, a physician, scholar, and citizen of Vicenza resident in Venice, was the son of Nicolosia and Paxino Mapello. He may not have practiced medicine. He received income from houses and land he owned in Vicenza. The date of Cassandra and Gianmaria’s marriage is not known though many writers suppose it to be 1499.

Mapello edited books published in Venice on logic, especially on sophismata or puzzling statements, by Antonii Andreae (1492 and 1496), Petrus Mantuanus (1492), and Gulielmus Hentisberus (1494). Judging from the books Mapello edited, he and Cassandra may likely have been intellectual equals. Cassandra’s letters to others suggest that they had a loving relationship. In her will of 1514, Cassandra’s aunt Bianca Trevisan de la Seda named Gianmaria as one of her executors. In 1515, Gianmaria wrote his own will before they departed for Candia (Crete). Stating that he was living in Santa Marina, he named Cassandra and his brother Agostino as his executors. He bequeathed to her money to invest in farmland. On their return to Venice in 1520, they survived a shipwreck but lost their possessions. Grievously weakened, Gianmaria died in Venice in late August 1520, leaving Cassandra bereft, but well-provided for financially. After her marriage, she used the name Cassandra Mapello, as, for example, in her unprobated will of 1543.

Other Significant Relatives:

Bianca (Blanche) Fedele Trevisan de la Seda (ca. 1440-1523), the elder sister of Angelo Fedele, was a key figure in Cassandra’s life. As the wife of Zuane Trevisan de la Seda (the brother of Cassandra’s mother), Bianca was also Cassandra’s maternal aunt. From her husband and his brother Domenico Trevisan de la Seda, Bianca inherited a substantial amount of real estate, property, as well as slaves, who were liberated by her at her death in 1523. Named in Bianca’s 1521 will, Cassandra was Bianca’s last surviving executor and beneficiary.

Matteo Fedele (1480-1555), a lawyer. Matteo was the son of Cassandra’s brother Alessandro. Matteo, and his brothers Vincenzo Fedele, Giovanni Battista Fedele, and Fedel Fedele, held high roles and offices in the Venetian government.

Antonia Lion (Leone), niece, daughter of Cassandra’s sister Polissena. Antonia was Cassandra’s primary heir.

Beneto Lion (Leone), husband of Antonia, a lawyer. Their sons were Paolo, Baldassare, and Lione Lion.

Niccolò Franco (ca. 1425– 499), named by Cassandra as a blood relative (meo consanguineo), he may have been her great-uncle, perhaps a brother of Cassandra’s grandmother Maria Fedele, but the exact relationship remains undetermined. He is a key figure in Cassandra’s life. Originally from Este, Franco rapidly rose in Church ranks. From 1475–78, Franco served as the Holy See’s ambassador to Spain where he pursued projects of clerical reform and directed the Inquisition’s interventions against Jews, conversos, and other “heretics.” After Franco’s return to Italy, he and his secretary Aurelio Augurello maintained contact with the Spanish court. Queen Isabella of Castile’s ten-year-long correspondence with Cassandra about her possibly coming to Spain began in October 1487, before her oratorical triumph in Padua. From 1485–1492, Franco was the papal nunzio to the Venetian republic, dealing with diplomacy and alliances. In 1485, Franco was named bishop of Parenzo (Poreč, Istria) and subsequently, bishop of Treviso. He ordered clerical and monastic reforms; established the Monte di Pietà of Treviso; and contracted with Pietro Lombardo to renovate the cathedral. In Constitutiones cleri Veneti, 1491, he published the first rules concerning the censorship of printed books. The first book he censored was by Pico della Mirandola, who would become a correspondent of Cassandra’s. Despite his assignments on the Venetian mainland, Franco lived in Venice, close to the Fedeles’ home at the monastery of SS. Giovanni e Paolo. He often stayed at his episcopal villa at San Virgilio di Montebelluna, surrounded by his Humanist friends, among them, several of Cassandra’s correspondents. Franco’s name, along with Angelo Fedele, Bertuccio Lamberto, and Francesco Fedele, figures in several documents related to family financial transactions.

Bertuccio Lamberto (ca. 1460 – 1522), Cassandra’s first cousin. He was the son of her mother Chiara’s sister Lucrezia Trevisan de la Seda and Domenico Lamberto. Cassandra honored Bertuccio at his graduation ceremony—at his invitation—in her Padua oration of 1487. He was a Canon of Concordia, and then rose to Protonotario Apostolico, and Primicerio of the Cathedral of Treviso. He was a close friend of Aurelio Augurello who wrote a poem dedicated to him; and a member of Bishop Niccolò Franco’s circle. Bertuccio’s tomb in Treviso was carved by sculptor Lorenzo Bregno. Bertuccio's niece, Lamberta Lamberto, was the mother of Cancelliere Grando Andrea Frizier, who would come to own Cassandra's portrait.

Alvise (Lodovico) Nicheta, a banker, was either an illegitimate brother or an illegitimate son of Cassandra’s uncle Zuane Trevisan de la Seda. In 1500, Cassandra sent a message to the Senate to try to spare him from punishment for coin-shaving.

Education

Of Cassandra’s education, Tomasini wrote, “her mother is said to be Barbara from the Venetian Leone family, at whose bosom she learned and practiced girls’ work.” But did Cassandra learn “women’s work?” In an oration before the Doge, she expressed contempt for women's tools such as the needle and the distaff. Documents show that Cassandra’s aunt Bianca Fedele Trevisan de la Seda, as well as other women in her intermarried maternal and paternal families, were role models for Cassandra. They taught her financial and managerial skills and supported the development of her exceptional self-confidence.

Her father Angelo instructed his daughter in Latin and Greek. At age twelve, she began ten years of study of Aristotelian philosophy, dialectics, theology, and the sciences with fra Gasparino Borro da Venezia at Santa Maria dei Servi. Some writers have suggested that Cassandra went off to study at the monastery’s school, but it is improbable. Santa Maria dei Servi is within easy walking distance of Calle de la Testa. Borro, who was not cloistered, probably came to the Fedele home.

Borro gave public lectures on astronomy. His published works include his commentary on Sacrobosco’s De Sphaera, Venice, 1494, and Triumphi, sonetti, canzoni e laude della Virgine Maria, containing over 200 literary compositions including an epic poem, sonnets, and songs written over decades, published posthumously, 1498. In letters to her friend Bonifacio Bembo, Cassandra referred to “our” Gasparino with admiration and affection. She wrote to high authorities in support of her teacher’s appointment as a preceptor at San Marco. Renowned for his preaching, Borro is likely to have instructed Cassandra in the rhetorical arts.

Angelo’s purchase of a book of Cicero’s letters, recorded in the register of Venetian bookseller Francesco de’ Madiis in February 1485 (more Veneto), is evidence that the pre-eminent classical exemplar for Venetian Humanist letter-writers was in Cassandra’s home a year before her earliest known letters are dated.

When Cassandra spoke in Padua at the baccalaureate ceremony of her cousin Bertuccio Lamberto in 1487, although she did not receive a degree, she implied that she deserved the same academic honors that her cousin received.

She wrote to Lodovico il Moro, Duke of Milan, on January 25, 1492 (more Veneto), that she was longing to study literature—“I was born to study”—and asked him to recommend her to the Venetian Senate.

Misogyny:

There were no sanctioned institutions in which Cassandra could study. In a letter to Ludovico il Moro (Tom. 55) Cassandra complained, “Indeed, I confess to you alone that some men envy the novelty of my talent, not recognizing what is unusual in a mind. Even so, I am accustomed to laugh at these men, following the habit of the philosophers. As long as I dwelt on the whims of the malevolent, it slowed me down in my writing.”

Cassandra’s correspondents and contemporaries damned her with faint praise, calling her an exception to her sex; or for having surpassed her sex; or that she was a Muse, or a goddess, or maybe really a man. Feng has argued that Ciceronian (male) amicitia provided no models for male admiration of women’s intellect. Cassandra’s correspondents lacked the rhetorical model and vocabulary to write to her as an intellectual equal, so they resorted to Latinized Petrarchian tropes to confront an accomplished woman. Feng also proposed that Cassandra’s correspondence with Isabella of Castile shows the tentative emergence of a language of female intellectual amicitia.

Surely frustrated by endemic societal misogyny, in her public speaking and correspondence she deployed conventional expressions of self-minimization to cater to male expectations, using self-effacement strategically and ironically.

Although nothing has survived to overtly document that Cassandra was singled out for aggressive mockery, Fregosa’s highly curious entry on Cassandra is worth signaling (Fregosa 1509, 8, 3). Within his entry praising the learned virgine veneta for accomplishments such as the recitation of Latin verses accompanying herself on a cithera, her oration at Padua, and her book on the order of the sciences, he writes the bizarre non sequitur, “But to return to Valerius’ sequence, we will write about examination by torture.”

Maturity:

The Fedele family was well-connected to powerful figures in the Church; the Venetian government; foreign rulers, nobility, and ambassadors; and government, medical, legal, business, and cultural figures throughout Italy.

In the years after her clamorous success in Padua, the Fedeles entertained many visitors who sought to meet and know her. Although no letters describe the physical environment of her home, Cassandra’s maternal uncle Domenico Trevisan de la Seda’s hand-written inventory of his personal possessions (1498) gives an idea of the family’s luxurious environment and furnishings. Poliziano’s description of his visit to Cassandra, when “she appeared to him like a nymph in the forest” is suggestive of a domestic classical performance. Perhaps it reminded him of witnessing the young Florentine Humanist Alessandra Scala perform Electra in her home.

Although there is little evidence that Cassandra traveled during the 1480s and 1490s, she did spend time in Padua and may have visited properties that both sides of her family owned on the mainland. We do not know if she made an intended visit to Florence mentioned by Poliziano.

During the years 1475-1478, her great-uncle Niccolò Franco, the Apostolic Legate, was in Spain, he may well have mentioned his young relative back in Venice, the child prodigy Cassandra, who would have been just ten to thirteen years old. Yet as far as we know, it was not until 1487 that Isabella began to communicate with the 22-year-old Cassandra. Surviving letters spanning a decade between Isabella and Cassandra concern the realization of the Queen’s invitation to her to come to Spain as a court humanist and possible tutor to her children. Cassandra wrestled with the idea of leaving her family and Venice. Convinced by Franco’s secretary, (and) her friend Aurelio Augurello, Cassandra finally agreed to accept the invitation. The exchange of letters between the two about the possibility of the trip continued into the 1490s, but Cassandra was never able to go to Spain. Some biographers speculate that the Venetian government considered Cassandra an “ornament of the State” and forbade her departure, but no official documents concerning this matter have been found in Venetian archives. Perhaps her health, or war, rendered it impossible.

In several letters, Cassandra speaks of her intense and exhausting efforts at studying, letter-writing, and greeting visitors and refers to bouts of a recurring but undefined illness. She seems to have delayed marriage in favor of her studies. When Alessandra Scala wrote to her asking for advice about marrying, Cassandra advised her to do what she thought was suitable to her nature. But after both her mother and her teacher Gasparino Borro died when Cassandra was about thirty-four, she married Gianmaria Mapello. A physician and citizen of Vicenza living in Venice, Mapello was extremely learned. Copies of three books on philosophy and logic that he edited reveal that he may have been an intellectual equal to Cassandra. Judging from Gianmaria’s words about her in his will, and from her letter to Pope Leo X after her husband’s death, it is likely that they had mutual affection and a happy marriage.

There is little documentation of her intellectual activity after 1500. In 1501, Venetian diarist Marino Sanudo alluded to her as “la poetessa” when she tried to intervene on behalf of Alvise (Ludovico) Nicheta. This banker, who had been arrested for coin-shaving, was probably a brother, or Illegitimate son, of her uncle Zuane Trevisan de la Seda. Financial instruments from the 1480s record several instances in which Nicheta played a role as a lender in Fedele and Trevisan de la Seda land transactions. In 1495 and 1496, Cassandra’s aunts Bianca and Lucrezia invested her late mother Chiara’s dowry with Nicheta. In two letters (Tom. 64 and 79) to an unnamed Humanist friend, Cassandra named her dear relative Ludovico Nicheta. The punishment for Nicheta’s crime of destabilizing Venetian currency was to have a hand cut off and an eye gouged out. Although Cassandra sent a message to the Senate—via her friend, the French ambassador Accursio Mayner—asking for mercy, Nicheta’s punishment was carried out.

From 1515 to 1520, Cassandra and Gianmaria spent five years in Crete. On their return to Venice, they survived a shipwreck but lost their possessions, likely including their books and papers. Severely weakened from the ordeal, Mapello died in late August 1520, when Cassandra was fifty-five years old.

Tomasini’s Vita and other accounts of her life state that Cassandra lived in extreme poverty after her husband’s death. The sources of this assertion include Cassandra’s own statements in letters she wrote to Popes Leo X (1521) and Paul III (1547) appealing for financial subventions. In her 1534 and 1537 redecime (tax declarations), she declared that she and her sister were poor. But her assertions of poverty can now be demonstrated to be part of a complex Fedele family economic strategy designed to comply with terms of her aunt Bianca Trevisan de la Seda’s will of 1521, of which Cassandra and her sisters were executors and beneficiaries. Bianca decreed that after their deaths, her property should pass from poorest niece to poorest niece.

Documents show that during the 1520s to 1540s, Cassandra managed family properties and served as an executor of her wealthy aunt’s estate. In 1543, Cassandra wrote a will in her own hand, in volgare (recently discovered, un-probated, and quite different from her probated will of 1556.) In 1548, she was elected prioress of the Ospedale de le Donzelle at San Domenico di Castello. That year, her testimony was recorded in a case related to her aunt’s will before the Giudici del Proprio and Giudici del Petizion. In her 1556 will, she named her niece Antonia her universal heir and left her books “here in the priory” to her grandnephews. At her death on March 24, 1558, she was given a public funeral and on March 26 was buried in the cloister of San Domenico. In 1807, the Austrian administration destroyed the church and monastery of San Domenico di Castello, including Cassandra’s burial monument, to create a space for public gardens.

In May 1558, just a few months after her death, the Abbess of the Monastery of Spirito Santo accused Cassandra and her niece Antonia’s husband, the lawyer Beneto Leone, of collusion to commit fraud concerning the will of Bianca Trevisan de la Seda. Litigated in the Venetian courts, the case dragged on for over a century, until 1696.

less

Significance

Works / Agency

Cassandra wrote primarily in Latin: the texts of three of her public orations survive, along with about 130 letters.

Known examples of Cassandra’s voice in volgare are: transcriptions of her oral tax declarations (1514, 1525, 1534, and 1537); her un-probated will of May 17, 1543, written in her own cancelleresca corsiva hand (ASVe, Notarile, Testamenti, notaio Licinio, b. 577. 13); her probated will of August 28, 1556 (ASVe, Notarile, Testament, notaio Baldigara, b. 70.50) a note of credit to the monastery of San Domenico, June 6, 1555 (ASVe, Atti Benedetto Baldigara, Busta 3900); and her holographic receipt for a copy of her will to the notary, October 24, 1556.

Foresti wrote that she presented an oration in volgare that equaled the excellence of her Latin orations, but this text has not survived.

Orations and Publications:

Oratio pro Bertuccio Lamberto.

Although Foresti and Betussi say that she was invited to lecture several times in Padua, only one such oration is known. Invited by her cousin Bertuccio Lamberto, Canon of Concordia, to deliver an address at his liberal arts degree-awarding ceremony at the University of Padua in November 1487, she spoke before an audience of academics and civil authorities. She was the first woman to do so. In her (ironically) self-minimizing introduction, she says she should be stuttering and stammering, but then declares, let the fear end here. She addresses her audience’s low expectations and then presents a well-constructed argument filled with classical citations concerning the benefits of studying philosophy. In her conclusion, she praises Padua as a new Athens; thanks those who came because you are here today in great numbers to honor my kinsman Bertuccio and me who came to praise him; and then confidently implies that she too is worthy of the academic degree received by her cousin. In “Cassandra Fedele as a Latin orator” (1986), Carl Schlam published a detailed structural analysis of the exordio of Pro Bertuccio Lamberto. He revealed the rhythm and arrangement of phrases, the patterns and variety, in short, the prose artistry that made her oration so impressive.

News of Cassandra's oration soon spread throughout Italy and abroad by word of mouth, letters, and in print. Fedele's Oratio Pro Bertuccio Lamberto, Venice, 1488, was the first secular book written by a contemporary woman to be printed and published. In addition to Cassandra's oration, it contained letters of praise from the University of Padua's rector Lodovico da Schio and Cassandra's reply to him; and a letter from Angelo Tancredi, as well as a Sapphic ode by Francesco Negri. The book spread Cassandra's fame widely beyond those who were present at the event. Thanks to Hartmann Schedel's eyewitness report from Padua, the oration was published in Nuremberg in 1489. The Nuremberg edition contains an additional letter to Cassandra by editor Petrus Abietiscola Negromontanus (Peter Danhauser), as well as German Humanist Conrad Celtis's Ode to Apollo. A woodblock print attributed to the young Albrecht Dürer with an imaginary depiction of Cassandra speaking before Bertuccio at the ceremony in Padua, serves as a frontispiece. In 1494, the Venetian edition of the Pro Bertuccio Lamberto was republished in Modena. Tomasini published the oration again in 1636.

Cassandrae Fidelis de laudibus litterarum oratio, (before 1500, text incomplete).

Cassandra spoke before the Doge Agostino Barbarigo, ambassadors, a delegation from Bergamo (probably including Foresti), Venetian Senators, and other guests, including the Humanist Giorgio Valla, at a reception on the second night of Christmas. She praised rulers who make their states more humane by encouraging study of literature and the liberal arts:

which for humans is useful and honorable, pleasurable and enlightening since everyone, not only philosophers but the most ignorant man, knows and admit that it is by reason that man is separated from beast……in my opinion men in paintings and even men’s shadows do not differ more from real human beings than do the uneducated and untaught from men who are imbued with learning.

In her conclusion, she asserted that women should be able to study literature. She summons the martial image of Alexander the Great, who, under Aristotle’s teaching:

surpassed all other princes and emperors in ruling justly, prudently, and gloriously... And when I meditate on the idea of marching forth in life with the lowly and execrable weapons of the little woman—the needle and the distaff—even though it offers women no rewards of honors. I believe women must nonetheless pursue and embrace such studies alone for the pleasure and enjoyment they contain.

Tomasini published this oration in 1636.

Cassandrae Fidelis oratio pro adventu seremissimae sarmaticae reginae. In April 1556, Cassandra, now near age 91, presented an oration on board the Venetian State’s ceremonial yacht Bucintoro at the command of the Venetian Senate, to celebrate the arrival in Venice of Bona Sforza, Queen of Poland. In this oration, themes of joy, women, age, memory, learning, and power come together. Cassandra speaks of the old age which lies heavy on my shoulders. She praises the learned Queen for her:

incredible gifts of the mind and her singular prudence in ruling your people in peacetime and the fortitude of your admirable mind amid the winds of war.

This oration is Cassandra’s only known composition that evokes the beauty of Venice, her water city.

But why does the slowness of this tongue of mine not travel to the place where the most sublime desires of mind and genius escape, to this placid sea, this serenity of air, this sweet and lightly spiraling breeze to show favor to the wishes of our august Senate? Who does not see that your entrance in the future into the heart of this city will be happier since the heavens, the land, and the very seas themselves seem to welcome and honor this queen with joy.

Tomasini published the oration in 1636, along with a reminiscence by Cassandra's grandnephew Baldassare Leone who recounted (in Tomasini, 1636 and 1644) that the Queen took a gold necklace from around the neck of one of her ladies-in-waiting and gave it to Cassandra. The next day, Cassandra returned the necklace to Doge Francesco Venier and the Senate, telling her that gold had never meant anything to her, and she was not worthy.

Letters:

Foresti (1497) and Betussi (1545) wrote that Cassandra maintained a vast correspondence and wrote elegant letters in Latin and Greek. Tomasini, 1636, published letters he found in Padua collections ("as many as have been possible to find so far"): 123 letters that Cassandra wrote and seven received, dating from 1487-1499, 1514, and 1547. These can only have been a fraction of her correspondence, which comprises a who's who of named correspondents. Although Cassandra corresponded primarily with men, the number of letters she exchanged with powerful and learned women is notable. Along with named and tentatively identified correspondents, including relatives and friends, there are many unnamed recipients.

A list of selected correspondents includes:

Secular rulers, nobility, and courtiers King Ferdinand II of Aragon, Queen Isabella of Castile; King Ferrante II of Naples; Beatrice of Aragon, wife of Mattias Corvinus, king of Hungary; Eleanora of Aragon, duchess of Ferrara, wife of Ercole I d’Este; Beatrice d’ Este, duchess of Bari and Milan; her husband Ludovico Sforza, duke of Milan and Bari, 1490; Francesco Gonzaga, marquis of Mantua, married to Isabella d’Este, daughter of Eleanora of Aragon; Gaspare of Aragon; King Louis XII of France; the French ambassador Accursio Maynerio; and Lorenzo de’ Medici.

Ecclesiastics Pope Alexander VI; Pope Leo X; Pope Paul III; Pier d’Aubusson; Niccolò Franco, bishop of Parenzo and Treviso; Domenico Grimani, Patriarch of Aquileia; Baldassare Fedele, archbishop of Monza; Matteo Bosso.

Humanists and academics. Aurelio Augurello; Ermolao Barbaro; Bonifacio Bembo; Girolamo Broianico; Girolamo Campagnola; Ambroz Mihetić (Ambrosius Miches); Pico della Mirandola; Francesco Negri; Benedetto Missolo Pagano; Pavao Paladinić (Paolo Paladini); Angelo Poliziano; Paolo Ramusio; Marcantonio (Coccio) Sabellico; Panfilo Sasso; Alessandra Scala; Bartolommeo Scala; Ludovico da Schio; Gianfrancesco Superchio (Filomuso); Angelo Tancredi, 1488; Niccolò Leonico Tomei; and Giovanni Antonio Zabarino.

Her letters, written in Humanist Latin and inspired by Classical authors Cicero, Seneca, and Pliny the Younger, cover a wide variety of topics. Diana Robin identified several recurrent Humanist themes in her work: reason and eloquence as powers unique to humans; the importance of a liberal arts education; and the nature of friendship. Cassandra frequently discusses letter-writing itself, apologizing for her delay in responding. For example, in her letter to Ambrosius Miches, May 1487:

I came to the study of literature at the tenderest age, and ever since then I have received so many letters that I was not able to have any respite from writing. What is more, I have been continually surrounded in my own home by learned men who wish not only to visit with me but to enter into disputations with them. These things, then, have caused me to be a little slow to respond.

She and her correspondents exchanged letters filled with learned classical references, Humanist courtesies, mutual assurances of friendship, and congratulations. Sometimes, she dated in letters not only in kalends but in classical style, "a prima elementorum concordia olympiade." In several, she stated that she sought to achieve virtue, fame, and immortality. She thanked admirers for poetic compositions they sent in her honor. She petitioned higher authorities for their patronage and financial aid. She sought recommendations and willingly gave them on behalf of others. She wrote of her hope to be able to go to Spain and Isabella’s court. She fretted over the challenges of study; commented on news about family and friends; asked to pass along greetings to others; learned about her family history; and shared concerns about her and her sister’s health. Her tone ranges from formal and formulaic to informal and spontaneous; from strategically timid and self-abasing to confidently self-aware; and from serious to playful. Apart from pro forma Christian expressions in exchanges with clergy and secular rulers, most of her correspondence is infused with the classical, antique, and pagan spirit she and her Humanist friends appreciated. Her letters give no indication of the intensity of her own private religious faith and practice.

Since Tomasini, other letters to and from her have emerged: from Laura Cereta, 1487; to Ludovico il Moro, 1492; and from her nephew Matteo Fedele (in volgare), 1556.

Poetry:

Although Cassandra was known as a poet, only three examples written by her are known to have survived.

Tomasini quoted lines that she, an older woman, inscribed on her portrait painted in her youth by one of the Bellinis.

Calcavi qua omnes optant meliora secuta,

Iam celebris passim docta per ora vagor,

Bellinusq; minor me priscis amulus arte

Et vivis studio rettulit effigie.

Domenico Cascasi (1973-74) published the carmen of praise she sent to Pope Paul III, 1547.

Lost Works:

Foresti (1497) reported that she was working on a book, Ordo scientorum, reviewing various philosophical sects. The fate of this missing, or perhaps never completed, work has been the subject of much inventive speculation.

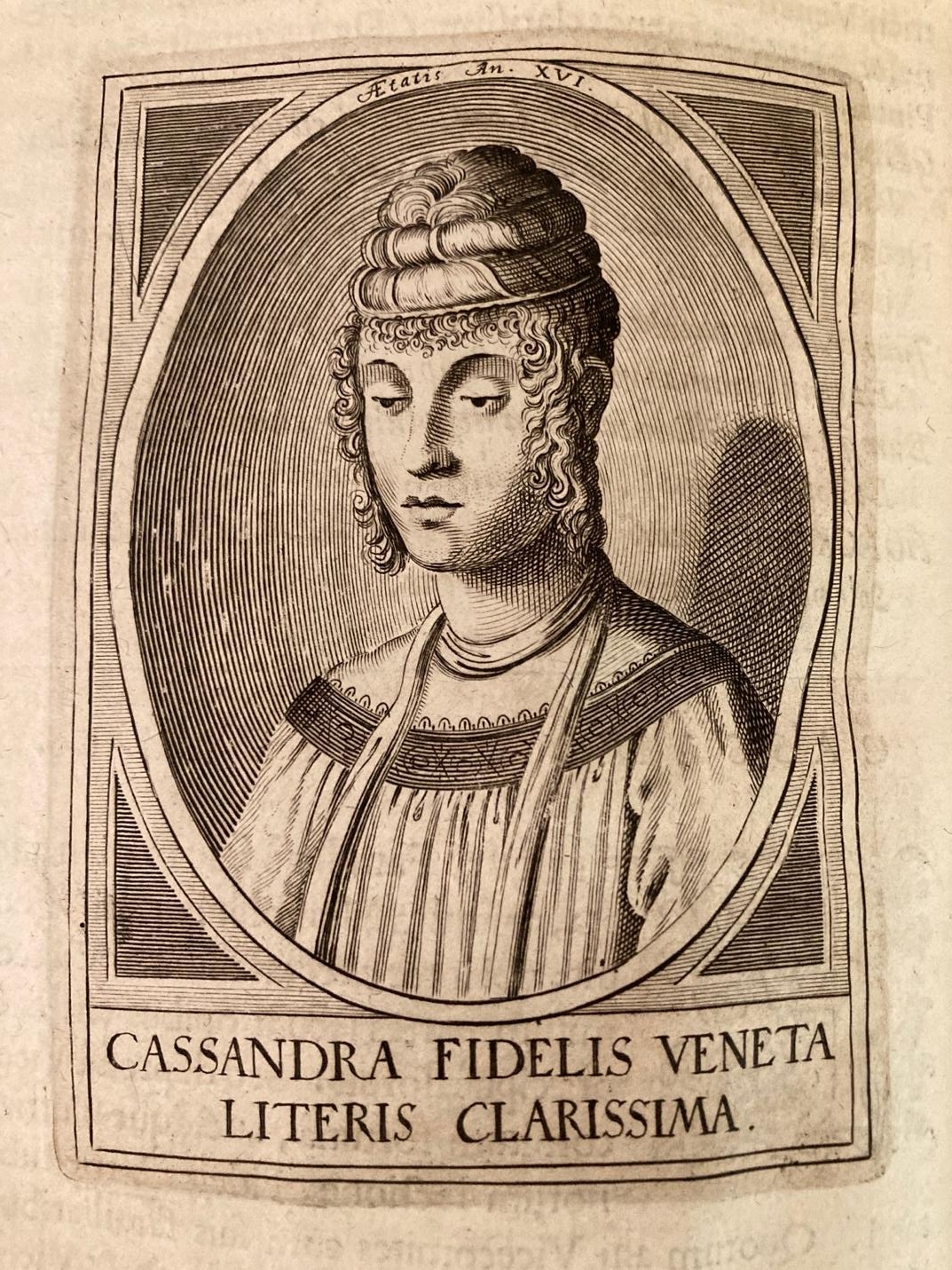

Portraits:

Lifetime portraits depict her with the pettinatura a fungo hairstyle, a deliberately transgressive and sexually ambiguous appearance. Her contemporaries’ verbal descriptions reveal that Fedele cultivated a distinctive appearance, perhaps dressing in a classicizing manner evocative of nymphs, Muses or Sibyls. Four lifetime depictions of Cassandra Fedele are known.

- The Bellini portrait itself is lost. Tomasini, 1636, published Giovanni David’s engraving after the portrait of the 16-year-old Cassandra as the frontispiece of the Vita. Tomasini published the engraving again in Elogia, 1644. Although the lines Cassandra herself inscribed on painting quoted by Tomasini (perhaps on the frame or back of the panel): “Bellini painted me when young” it is not clear from Cassandra’s lines whether it was Gentile or Giovanni Bellini who painted it. This portrait depicts her wearing the pettinatura a fungo, hair piled on top of the head and sidelocks, a style originally associated with Venetian prostitutes feigning to be boys to attract men seeking homosexual encounters. Although the fungo was banned by the Council of Ten in 1480, it became fashionable among Venetian women during the 1480s. Cassandra is shown with a thin scarf looped around her neck. She is dressed in a camicia (not outdoor clothing) and wears no jewelry. This portrayal establishes an iconography of Cassandra Fedele. The Bellini painting was the source image for a portrait of Fedele, ca. 1600-1650, in the collection of Cardinal Federico Borromeo. Later works based on the portrait engraving published by Tomasini include Giovanni Grevembroch’s watercolor, Donna Vana, ca. 1770, with its allusions to prostitution; an etching in Bartolommeo Gamba, 1826; a wood engraving in Album, Giornale letterario e di Belle arti, Rome, 1854; and Pietro Borro’s bas-relief marble tondo, 1860 (now at Palazzo Loredan, Istituto Veneto).

- A woodblock print depicts Cassandra delivering her oration in Padua in 1487. The imaginary image, published in Fedele’s Oratio pro Bertuccio Lamberto, Nuremberg, 1489, has been attributed to the young Albrecht Dürer.

- A bronze relief medallion by Niccolò Spinello (Fiorentino), ca. 1495. The recto portrays Cassandra in profile. The verso depicts Calliope, the muse of epic poetry, playing a viola da braccio. An inscription in Greek, from Hesiod, identifies her as the chief of the Muses.

- A woodblock print of Cassandra veneta virgo, in Jacopo Filippo Foresti of Bergamo, De claris selectisques mulieribus, 1497. In the entry on her, Foresti wrote that he had the portrait of Cassandra drawn and cut to preserve her likeness.

Several depictions of Venetian women wearing the pettinatura a fungo, made ca. 1480-1500, have been suggested as representing or reminiscent of Cassandra. The miniature in 13-year-old Vettor Capello’s manuscript panegyric to his grandfather, Doge Marco Barbarigo, 1486, (London, British Library) may represent a personification of Venice that alludes to Cassandra as oratrix. Several other images that are unlikely to be of Cassandra include Dürer’s drawing of two Venetian women, ca. 1495, (Vienna, Albertina); a Bellini drawing on blue paper in Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia di Belle Arti; and a painting by Carpaccio in Rome, Galleria Borghese.

Lifetime Fame

Ever since Giacomo Filippo Foresti of Bergamo published the entry “Divae Cassandrae Fidelis, virginis venetae” in his De claris selectisque mulieribus, (written ca. 1491, published 1497), an illustrated encyclopedia of 172 famous women from Eve to his own time, writers have followed him in declaring that Cassandra was “famous.” In Foresti’s late 15th century updating of Boccaccio, Cassandra was one of only fourteen contemporary women he featured. Foresti wrote that he had the woodblock portrait that illustrates the entry drawn and cut in order to preserve her likeness. In our own fame-obsessed time when Cassandra has become an iconic figure in women’s history, writers often say that Cassandra is famous because she was famous. Although her fame per se was an important justification, there have been many other reasons for praising and remembering Cassandra.

Foresti was not the first writer to praise Cassandra in print or even depict her. Around 1481 when she was sixteen, one of the Bellinis painted her. When she was in her twenties, praise of her—in the form of letters, poems, and printed visual images—had already appeared in the 1488, 1489, and 1494 editions of her oration. Dalmatian poet Paolo Paladino (Paladinic) published his poem dedicated to “Cas[s]andram Fidelem Veneta[m] virginem et vate[m]” in 1493. Niccolò Spinello (Niccolò Fiorentino, 1430–1514), sculpted a bronze relief medallion of her, ca. 1495. The recto portrays CASSANDRA FIDELIS, shown in profile. The verso depicts Calliope, the muse of epic poetry, playing a viola da braccio. A quotation in Greek from Hesiod encircles the image.

Foresti and other writers with first-person experience praised her not only for her fame but also for what she did (her orations, theological and philosophical debate, poetry, and performance of music) and how they perceived her (her youth, grace, modesty, and decorousness). They expressed admiration in various ways: classicizing-mythologizing (her Paduan Humanist friends called her miraculous, a vision, a living Muse, Calliope, a goddess, Camilla, warrior queen); classical-historical (you exceed Sappho, Hortensia, and Nogarola); Christian (decorous, blushing, chaste); political (the ornament of Italy, of Venice, I am happy to be born in your time); gendered (exceptional, childlike, a daughter, how could you be a woman?). Some of her Humanist admirers were baffled, tongue-tied, and sighing. Aileen A. Feng has argued that, lacking classical epistolary models for writing about and sharing intellectual friendships with women, they repurposed Petrarchan expressions of love, from Italian into Latin, to write to her.

Humanist-trained women took a different approach to addressing her. Writing in 1490, Queen Isabella of Spain, who considered Cassandra illustrious because of her learning, addressed a letter to Cassandra ingenua adolescentula. Brescian Humanist Laura Cereta (1469-1499) wrote to Bernardino Laurino, “you are not telling me anything new. Cassandra is good at everything.” (Cereta, Ep. 66).

Angelo Poliziano’s letter to Cassandra, beginning O decus, Italiae virgo! and his letter about her to Lorenzo de’ Medici were published in the Omnia opera Angeli Politiani, Venice, Aldus Manutius, 1498, Book 3. The only woman in this ne plus ultra of Humanism, the inclusion of Poliziano’s letters to and about her guaranteed the immortality she sought.

In 1500-1558, the years from Cassandra’s maturity to extreme old age when Italian became the dominant literary language, Fedele and other female Latinists became frozen in time. While Cassandra was still alive and in her 40s to 90s, encomiasts Fregosa (first printed edition, 1509), Ravisius (1521), Betussi (1545), and Egnazio (1554) still wrote of her as a virgin and prodigiously learned girl. As the first illustrious contemporary woman Lodovico Dolce named in the first edition of his Dell’ istituzione delle donne, 1545, Book 1, 18, the typographer set “CASSANDRA FEDELE della mia citta,” in all capital letters.

Transmission of Her Works and Posthumous Fame

Although today many writers assert that Cassandra was forgotten, she never really vanished from historical memory, scholarship, and art. Thanks to the preservation of some of Cassandra’s papers, the content of her work was not entirely lost. Eventually, she would transcend pure mythologizing. Her actual achievements would be studied.

In her will of 1556, Cassandra made a bequest of her residual property to her niece and universal heir Antonia (her sister Polissena’s daughter), and her husband, Beneto Leone, whom she called her nipote. Beneto Leone was her nephew by marriage. Several writers have perpetuated a misreading of the will to say that she left her property to the notary, also named Beneto (Baldigara.) She left her books to Antonia and Beneto Leone’s children. These great-nephews eventually gave her papers to Andrea Frizier (1514-1581), who served as Cancelliere Grando of the Venetian Republic from 1575 to his death. Frizier was the Leones’ collateral relative by marriage through his first wife, their cousin Camilla Fedele (died 1558; daughter of Angelica Vidal and Matteo Fedele, son of Alessandro—son of Angelo Fedele).But Frizier was also directly related to Cassandra's mother and the Trevisan de la Sedas through his mother, Lamberta Lamberto. She was a niece of Bertuccio Lamberto. It is not clear whether Cassandra’s letters and the Bellini portrait were among the papers the Leones gave to Frizier. Camilla Fedele may have inherited the painting directly from her father. Tomasini said only that the painting was in Frizier’s house. In his will of 1578, Frizier left his books and papers to a daughter—also named Camilla—and a son, Carletto, his children by Emilia Marcello in secondo matrimonio.

Cassandra was remembered in Francesco Sansovino’s Venezia Città Nobilissima, 1581. He highlighted Cassandra as a most notable writer and orator during the reign of Doge Agostino Barberigo (Book XIII) and he described her burial place (Book I).

Painted towards the mid-1600s, a portrait of Cassandra in a series of portraits of over 200 illustrious learned men and women was displayed in Cardinal Federico Borromeo’s Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan.

By the early 17th century, Cassandra’s papers and the Bellini portrait were in Padua collections. The manuscripts were in the collection of Giorgio Raguseo, a professor and natural philosopher. In 1622 when Raguseo died intestate, his possessions were sold at auction. Evangelista Zagaglia, Alessandro d’Este, and Giovanni Battista Fichetto in Padua were some of the collectors who acquired her papers. Paduan collector and priest Lorenzo Pignoria (died 1630), owned a portrait of Cassandra, which was displayed as one of four images of illustrious women in his private museum. His friend Paduan priest and scholar Giacomo Filippo Tomasini wrote Lorentii Pignorii, vita, Bibliothecae et Museum, describing Pignoria’s collection, 1631.

In 1636, Tomasini published Clarissimae Feminae Cassandrae Fidelis Epistolae & Orationes, his compilation of Cassandra’s known writings. The French scholar and bibliophile Gabriel Naudé (1600-1653) wrote the introduction. Naudé had published a book in 1627 on how to establish a library; he was in Padua and Venice to buy books; and he would become the founder of the Mazarine library in Paris. Tomasini based the twenty-two page Cassandrae Fidelis Vita prefacing the letters and orations on Paolo and Baldassare Leone’s somewhat inaccurate and now lost remembrances of their great-aunt. The Vita was illustrated with an engraving by Giovanni David (attrib.) after the Bellini portrait, of Cassandra at age sixteen. This portrait was probably the image that was in Pignoria’s private museum, but Tomasini added that he himself now had the painting and quoted Cassandra’s poem on the frame (on the verso?), “Bellinus minor me prixit.” The Vita includes the first account of the dispersal of her works, including a list of libraries where her books could be found.

The collection of 128 letters sent and received that Tomasini published (“as many as have been possible to find so far”) were loaned to him by Zagaglia, d’Este, and Fichetto. These letters were evidence of the astonishing scope of her connections. Tomasini’s book included two previously unpublished orations: Cassandrae Fidelis de laubibus litterarum oratio and Cassandrae Fidelis oratio pro adventu seremissimae sarmaticae reginae. A few years later, Tomasini published Elogia virorum literis & sapientiai illustrium, 1644, containing a shortened version of the 1636 biography, the portrait engraving. The book also contained entries on Isota, Angela, Genevra, and Laura Nogarola; Laura Cereta; Hypsicratea; and Moderata Fonte. Few of Cassandra’s original manuscripts are known, which would provide an opportunity to compare and judge the accuracy of his transcriptions. But a comparison of Laura Cereta’s manuscripts with Tomasini’s publication of her works, 1640, reveals that he was faithful to the Brescian Humanist’s texts.

In 1654, Tomasini published a history of the University of Padua in which he listed Cassandra’s oration for Bertuccio Lamberto as the significant event for 1487, (Book IV, p. 397). He referenced his own book of her letters and orations. After Tomasini’s final mention of her in 1654, Cassandra’s orations, learning, fame, and image gradually slipped out of popular Venetian and Paduan consciousness. She was eclipsed by the learned Venetian Elena Corner Piscopia who, in 1678, became the first woman to earn a doctorate at the University in Padua.

Tomasini’s two Vitas would become the source for subsequent biographies of Cassandra. During the 18th century, Louis Moréri’s Le Grand Dictionnaire, Paris, 1707, vol 2, 100, included an entry on Cassandra Fedele that cites Tomasini and mentions his publication of her letters. Christian Gryphius, Vitae Selectae Quorundam Eruditissimorum ac Illustrium Virorum ut Helenae Cornarae et Cassandrae Fidelis, published in Bratislava, Poland, 1711, featured Fedele and Elena Corner Piscopia. Jean-Pierre Niceron’s encyclopedia, Paris, 1729, included an extended entry on Cassandra. Venetian Rococo sculptor Giovanni Bonazza (1654-1736) created a marble portrait bas-relief of her in his series of sixty-four illustrious men and women. Literary encyclopedist Francesco Saverio Quadrio included an entry on Cassandra Fedele in Della storia e della ragione di ogni poesia, 1741.

Venetian historian Flaminio Corner’s Ecclesiae venetae, 1749, an encyclopedic work on the churches of Venice, references Tomasini on Cassandra, and cited San Domenico’s necrology records for her burial date. In his grand poetic composition, Le Donne Illustri Canti Dieci, Abate Francesco Clodoveo Maria Pentolini, 1776, dedicated a stanza to her.

Although Cassandra’s contemporaries emphasized her virginity and chastity, by the second half of the 18th century, the figure of Cassandra began to take on a variety of sexual and asexual connotations. Giovanni Grevembroch (1731-1807) copied the engraving of Cassandra after Bellini, for his watercolor, Donna Vana, in Gli abiti de Veneziani (Venice, Correr, ms. Dolfin Gradenigo, vol. 3, 112). Cassandra’s portrait now represents a woman with a pettinatura a fungo, the forbidden 15th century hairstyle worn by Venetian prostitutes who cross-dressed as boys.

In the world of 18th century theater, Cassandra Fedele was remembered as the young Venetian woman who delayed marriage in favor of her studies. She was reimagined as a character in plays and operas by Giovanni Bertati and Gennaro Asterita: I visionari, 1772; I Filosofi immaginari, 1774; and Li Astrologi Immaginari, 1774. In these light-hearted musical dramas performed throughout Italy and abroad, a young woman named Cassandra—who has an aria—prefers studying philosophy to men; she goes up on the roof to look through a telescope at moons of Jupiter; she agrees to enter a sex-free marriage with a studious young man.

Throughout the 19th century, Cassandra was brought into the construction of a new Venetian and, later, Italian national iconography. Women writers, for whom she represented women’s independence and agency, recognized and wrote about her as a kindred spirit.

British feminist Mary Hays, citing the French encyclopedist Pierre Bayle, included an entry on Cassandra Fedele in her Encyclopedia of feminine biography, 1803. During the French and then Austrian domination of Venice, the Corfiot-Venetian writer and translator Countess Maria Pettretini planned a series of moralizing biographies of admirable women to serve as inspirational examples to girls. Who better, she asked, to begin her series with than by writing about the virtuous, motherless, and accomplished Cassandra Fedele? Petrettini credited Sante della Valentina, priest and chaplain of the Scuola Grande di San Rocco, for having inspired her to write her Vita di Cassandra Fedele, 1814 (republished 1852). Petrettini contributed no new documentary evidence but, following the outlines of Tomasini’s Vita, she imaginatively described Cassandra’s home life, feelings, and life in Crete,

Provoked by the Austrian administration’s destruction of the church and monastery of San Domenico di Castello to create public gardens, Giustina Renier Michiel (Origine delle Feste Veneziane, 1823), wrote an extended meditation on Cassandra, whose tomb had been destroyed. Renier Michiel’s book subversively transformed Cassandra into a Venetian cultural heroine who would bloom during the Risorgimento as Venice joined Italy.

Bartolommeo Gamba’s anthology of essays on twelve notable Venetian women, Alcuni ritratti di donne illustri delle provincie veneziana, 1826, included a pure line etching in a neo-classical style, reprising the Giovanni David engraving after the Bellini portrait. The entire edition of Gamba’s book created as a wedding present.

Count Leopoldo Ferri listed books by and about “Cassandra Fedele-Mapello” in the catalogue of his library, with notes on their rarity, in Biblioteca femminile, Padua, 1842.

A wood engraving after the Bellini portrait illustrates an essay on Cassandra in Album, Giornale letterario e di Belle arti, Rome, 1854. In 1858, Giovanni Paoletti published his Italian translation with annotations of Cassandra’s oration for Bona Sforza.

In The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, 1860. Jacob Burkhardt mentioned Cassanda Fedele as a well-educated woman who “made herself famous.”

The American feminist, Transcendentalist, and labor reformer Caroline Healy Dall (1822-1912) dedicated a chapter to Cassandra Fedele in her book, Historical Pictures Retouched, 1860. She comments on the flippant remark of Lady Morgan I (Sydney Owenson), Italy, 1821, about Poliziano and Cassandra, who seems “to have been much too pretty for a pedant; and was, perhaps, only a woman of genius.”

Romola, 1862, a novel by British author George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans) is set in Florence in the 15th century. The heroine determines to go “to the most learned woman in the world, Cassandra Fedele, at Venice, to ask her how an instructed woman could support herself in a lonely life there” (Chapter 26).

Giovanni Zuliani’s line etching, after Giuseppe Lorenzo Gatteri, Cassandra Fedele suona la lira, 1860, in the etching portfolio Storia Veneta in 150 tavole, 1863, depicts Cassandra playing the lyre while reciting poetry for the court of Doge Agostino Barbarigo. Foresti, 1497, who described her recitation before the Doge and guests on the day after Christmas was the literary source for the narrative image.

Commissioned to commemorate the 400th anniversary of her birth, Luigi Borro’s bas-relief marble tondo portrait of Cassandra, 1864-1865, in the Istituto Veneto’s Panteon Veneto, (Venice, Palazzo Loredan) also harks back to the portrait engraving in Tomasini although it is neither nor in three-quarters view nor tenderly Belliniesque. The severely neo-classicizing profile portrait foregrounds Cassandra’s pettinatura a fungo and side-locks.

In contrast, Irish Victorian artist Sir Frederick Burton (1816–1900) painted Cassandra Fedele, 1869 (Dublin, Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery of Modern Art), a highly finished watercolor. Set in an opulent Venetian Renaissance interior, it depicts Cassandra as a beautiful young woman with long and flowing auburn hair and a laurel crown, playing a viola da braccia. Preliminary charcoal drawings for the painting are in Dublin (National Museum of Ireland) and Ottawa (National Gallery of Canada).

Late 19th century scholars turned their attention to Cassandra. Henry Simonsfeld, 1893, published an article about Poliziano, Fedele, and editions of her Padua oration. Adriano Capelli, 1895, discovered manuscripts of letters exchanged between Cassandra and Ludovico il Moro.

Cesira Cavazzana’s magisterial research, Cassandra Fedele, Erudita veneziana del Rinascimento, 1906, still stands as the most thorough critical evaluation of the biographies and the historical record. Published in Fascist-era Italy, Maria Bandini Buti’s Poetesse e Scrittrici, Enciclopedia Biografica e Bibliografica Italiana, 1941, contains an entry on the married “Cassandra Fedele-Mapelli” including a useful bibliography that cites obscure 19th and 20th century sources.

In the second half of the 20th century, Cassandra re-entered the Feminist pantheon when American artist Judy Chicago included her as one of hundreds of significant women whose names are written on the ceramic tile floor in her iconic artwork, The Dinner Party, 1974-79 (New York, Brooklyn Museum).

Recent Studies:

Thanks to modern translations, Cassandra’s are now available to a wider audience: Giovanni Paoletti (Italian, 1858); King and Rabil, English, 1983 and 1992; Diana Robin (English, 2000); Antonio Fedele (Italian, 2010); Alessandra Luz Salinas Guillen (Spanish/Castillian, 2011); Mercedes Arriaga Flóres and Daniel Ceratto, eds. (Spanish/Castilian, 2021); and Maria-Isabel Segarra Anon Catalan, 2024). Giada Tonetto is currently working on a new translation and critical edition in Italian. The notes in the critical editions of Cassandra’s orations and letters edited by Diana Robin; Mercedes Arriaga Flóres and Daniel Ceratto; and Salinas Gullen contribute valuable information to the historical record.

Since the 1970s, scholars have analyzed the form and content of Cassandra’s writings illuminated by Feminism and women’s studies. Essential studies include works by King and Rabil; Jardine; Schramm; Cox; Robin (especially The Rhetorics of Life-Writing), Ross; Feng; and Arriaga Flóres.

But the limited corpus of writings that scholars have had to work with, such as Tomasini’s error-filled Vita, and only the three orations and 130 letters, are just a fraction of what she must have written and received, These have shaped subsequent scholars’ assumptions and conclusions. Recent writers have focused on her rhetoric and her gendered, self-deprecating, minimizing vocabulary.

Margaret L. King (1976) judged that Cassandra’s work was “Her intellectual achievements were mediocre. Unrelievedly conventional…little thought, less feeling.” Her orations were routine. She was raised beyond her merits… she was trained for youthful success, but accorded only indifference once her youth had passed.”

In her influential article, Her Father’s Daughter: Cassandra Fedele Female Humanist of the Venetian Republic (2007), Sarah G. Ross explored rhetorical strategies–what she termed the father-daughter paradigm–that Cassandra used to position herself as a daughter in relation to unrelated male correspondents and audiences.

Aileen Feng’s important study of Cassandra’s letters understood in the context of Ciceronian and Petrarchian Humanism pinpoints the issue that Cassandra and her correspondents lacked the vocabulary for an easy give-and-take between men and women as intellectual equals. "Where there is no precedent for male-female correspondence, Petrarchan conceits and tropes fill a need for finding a linguistic model that adequately expresses a sense of awe and wonder when confronting a learned woman."

Lacking more written evidence, scholars have had to accept the fact that Cassandra earned her reputation as a brilliant orator and debater, and that she was more astonishing in person. In need of refreshment, the field of Cassandra Fedele-studies risked becoming derivative and re-iterative. Yet, thanks to the work of scholars with fresh perspectives working in a wide variety of fields including neo-Latin; gender studies; history of Dalmatia; history of Spain; history of art; printing history, gerontology; psychology; and feminist biographical retrieval initiatives, the study of Cassandra is becoming reinvigorated.

For example, Vincenzo Farinelli, in “Cassandra Fedele come Faustina”in the catalogue of the exhibition, Le Trecce di Faustina: Acconciature, donne e potere nel Rinascimento, 2023, proposed the connection of Cassandra’s distinctive hairstyle and appearance to images of the Roman Empress Faustina the Elder.

Kathleen French applied principles of modern positive psychology to search for evidence of happiness in Cassandra’s writings and life In Five Venetian Women Writers: in Search of Happiness (2025). French argues that Cassandra was happy when she was young and at the height of her powers and human connections. She had a sense of agency, and she felt celebrated. Writing itself brought Cassandra happiness. As Cassandra’s youth, beauty, and celebrity waned, she must have felt a sense of disappointment later in life.

In Methuselah’s Children: The Renaissance Discovery of Old Age (book in development), Hannah Marcus argues that Cassandra’s oration for Bona Sforza and her “public performances were part of a broader culture in sixteenth century Italy that at once valorized and made a spectacle of the elderly in the space of the city.”

Amy Worthen’s discovery of the sealed autographic will of “Cassandra, relicta di Gianmaria Mapello,” 1543, written in volgare led, in 2021, to the discovery of hundreds of pages of documents generated in the monastery of Spirito Santo’s lawsuit against the heirs of Bianca Trevisan de la Seda. By identifying Cassandra’s mother, Chiara Trevisan de la Seda, and over one hundred additional relatives, this archival treasure trove offers new ways to understand, challenge, and revise understanding of Cassandra and the Fedele family. Worthen has written on portraits of Cassandra Fedele; on the identification of Cassandra’s mother; on Cassandra’s teacher, Gasparino Borro; on Spirito Santo’s accusation of fraud; and on the reception of Cassandra’s work and image by 17th century Paduan scholars and collectors.

Cassandra Fedele in Contemporary Culture

Via Cassandra Fedele is a street in Mestre (Metropolitan Venice). Student housing (residenza universitaria ESU) in via Fratelli Bandiera 74, Marghera, is named for her. Cassandra Fedele is the name of a luxury apartment at the Ospizio delle Donzelle, a B&B located on Via Garibaldi at the former site of the Ospedale de le Pute at San Domenico di Castello. “Cassandra Fedele” is a model of a wedding dress in the Luxury line of the Ukrainian bridal company, Innocentia.

Matteo Bergamelli’s watercolor sketch, after the engraving of the Bellini portrait, illustrates Venetian folklorist Alberto Toso Fei’s article on Cassandra (Gazzettino di Venezia, September 2, 2021), Cassandra she no longer looks down demurely. Her left eye begins to meet the gaze of the viewer. Her sidelocks are wildly emphasized.

In 2024, the District of Thrissur, in the State of Kerala, India, revised its school textbooks to be more gender-inclusive in academic subjects. The tenth-grade social sciences textbook has a page featuring Cassandra Fedele.

Five hundred years after Foresti wrote about Cassandra as a famous woman in De plurimis claris selectisque mulieribus, the Senate of the Republic of Italy included Cassandra in Storie d’ingegno e di Coraggio, Profili di Donne che Hanno Fatto L’italia, a book of biographies and images of ninety-five women who created Italy.

less

Bibliography

Primary

Fidelis, Cassandra, Oratio Pro Bertuccio Lamberto, Venice: Johannes Lucilius Santritter and Hieronymus de Sanctis, 19 Jan. 1488/89.

Fidelis, Cassandra, Oratio Pro Bertuccio Lamberto, Nuremberg : Peter Wagner, after 22 Nov. 1489.

Fidelis, Cassandra, Diuae Cassandræ fidelis virginis Uenetæ in gymnasio Patauino pro Bertutio Lamberto canonico Concordiensi liberalium artium insignia suscipiente. Oratio. Dominicus Rocociolus, Modena, 1494.

Fidelis, Cassandra, Clarissimae foeminae Cassandrae Fidelis Venetae Epistolae & Orationes Posthumae, numquam antehac editae. Iac. Philippus Tomasinus e M.SS. recensuit, praemissa ejus Vita, Argumentis, Notisque illustravit. Padua : Pasquati, 1636

Translations and critical editions

Cassandra Fedele, Letters and Orations, Diana Robin, ed. and trans., Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000.

Cassandra Fedele, Orazioni ed Epistoli, Antonino Fedele, ed. and trans., Padua, Il Poligrafo, 2010.

Cassandra Fedele: Ecos de una voz silenciada: (Discursos), Salianas Guillen, Alejandra Luz, Samsara, Mexico D.F., 2011.

Cassandra Fedele. Arriaga Florez, Mercedes & Cerrato, Daniele (eds.) & Moreno-Lago, Eva (trans.) & Duraccio, Caterina, Madrid: Dykinson e-book, 2019.

Salinas Guillen, Alejandra Luz, Cassandra Fedele: Ecos de una voz silenciada: (Epistolario), Kindle edition, 2020.

“Cassandra Fedele: Epistolaris i oratòries”. Segarra Añón, Maria Isabel, Catalan trans. and notes. 2024.

Paoletti, Giovanni, Orazione di Cassandra Fedele volgarizzata da Giovanni Paoletti col testo a fronte e con annotazioni, Venice, 1858.

King, Margaret L. and Rabil, Albert, eds and trans., Her Immaculate Hand: Selected Works By and About the Women Humanists of Quattrocento Italy, Binghampton, NY, 1983, rev. ed.,1992.

Studies

Arriaga Flórez, Mercedes, “Cassandra Fedele: Esa Rara y Exelente Mujer“, in Mujer, Biblia y sociedad, Nuria Calduch-Benages y Guadalupe Seijas de los Ríos-Zarzosa (eds.). Estella (Navarra), Editorial Verbo Divino, 2021, 85–105.

Betussi, Giuseppe, Libro del M Giovanni Boccaccio delle donne illustri tradotto per Messer Giuseppe Betussi, Venice, 1545.

Bogdan, Tomislav, “Cassandra Fedele And Her Dalmatian Correspondents”, in Živa Antika, 68 (1-2), 99–124, January 2018.

Buti, Maria Bandini, Poetesse e Scrittrici, Enciclopedia Biografica e Bibliografica Italiana, 6, Rome: Tosi, 1941, 257-259.

Cappelli, Adriano, “Cassandra Fedele in relazione a Lodovico il Moro” in Archivio Storico Lombardo : Giornale della società storica lombarda (1895 dic, Serie 3, Volume 4, Fascicolo 8).

Cascasi, Domenico. Il Carteggio di Cassandra Fedele, tesi di laurea in Filologia medievale e umanistica, Padua, 1973-74

Cavazzana, Cesira, “Cassandra Fedele, erudita veneziana del Rinascimento”, in Ateneo veneto, XXIX, vol 2, 1906, pp. 74-91, 249-75, 361-97

Clark, Leah R. Libri e Donne: Learned Women and Their Portraits, thesis, Courtauld Institute of Art, 2005.

Corner, Flaminio, Ecclesiae venetae antiquis monumentis nunc etiam primum editis illustratae, Venice, 1749, vol 7, 345

Cox, Virginia, Women's Writing in Italy, 1400–1650. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008.

Dall, Caroline Wells Healey, “Cassandra Fedele”, in Historical Pictures Retouched, Boston: Walker, Wise, 1860, 62-70

Documents: Archivio di Stato di Venezia, Spirito Santo, bb. 7 and 24.

Documents: Cassandra Mapello, rl. Gianmaria, testamento 17 May 1543. Archivio di Stato di Venezia: Notarile. Testamenti. (Licinio), bb. 577-578, 13

Dolce, Lodovico (1508-1568), Dialogo; della institution delle donne. Venice: Gabriel Giolito de’ Ferrari, 1545

Egnazio (Giovanni Battista Cipelli), De exemplis illustrium virorum Venetae civitatis atque aliarum gentium,published posthumously, Venice, 1554, 288.

Farinella, “Vincenzo. Cassandra Fedele come Faustina”, in Le Trecce di Faustina: Acconciature, donne e potere nel Rinascimento, Edizioni Gallerie d’Italia, Vicenza/Skira, 2023.

Feng, Aileen A. “The Spectacle of Woman: Cassandra Fedele’s Oration for Bertuccio Lamberti (84-94) in the chapter “In Laura’s Shadow: Gendered Dialogues and Humanist Petrarchism in the Fifteenth Century” (68-105), in Writing Beloveds: Humanist Petrarchism and the Politics of Gender. (Toronto Italian Studies.) Toronto, Buffalo, and London: University of Toronto Press, 2017.

Foresti, Jacobus Philipus (1434-1520). « De Cassandra Fideli veneta virgine oratatore et ph(ilosoph)a cap. 179 », in De plurimis claris selectisque mulieribus. Ferrara: Laurentius de Rubeis, de Valentia, 1497.

Fregosa, Battista (Fulgosius) Factorum dictorum, 1483. British Library, Harley MS 3878.

Fregosa, Battista. 1509. Baptistæ Fulgosi de Dictis Factis-Q3 Memorabilibus Collectanea, a Camillo Gilino Latina Facta. Fol. 278. Milan, 1509.

Fregosa, Battista “De Cassandra Fidelis virgine veneta”, in Factorum dictorumque memorabilium libri IX, supplement, Justo Gaillardo Campo, trans., Paris 1578.

French, Kathleen. Early Modern Women Writers Of Venice : Looking for Happiness. Routledge, 2025.

Gamba, Bartolomeo, Alcuni ritratti di donne illustri delle provincie veneziana, Venezia : dalla Tipografia di Alvisopoli, 1826

Griffin, Quinn Erin, Embodying Diotima: Classical Exempla and The Learned Lady, The Ohio State University, dissertation, 2016.

Gryphius, Christian, ed. Vitae Selectae Qvorvndam Ervditissimorvm Ac Illvstrivm Virorvm Ut Et Helenae Cornarae Et Cassandrae Fidelis, Vratislaviae [Now Wroclaw, Poland], 1711.

Jardine, Lisa, “'O Decus Italiae Virgo', or The Myth of the Learned Lady in the Renaissance”, in The Historical Journal, Cambridge University Press, vol 28, no. 4 (Dec., 1985), pp. 799-819.

Kristeller, Paul Oskar, ed. Iter Italicum : a finding list of uncatalogued or incompletely catalogued humanistic manuscripts of the Renaissance in Italian and other librairies. London ; Leiden : the Warburg Institute : E. J. Brill, 1965.

King, Margaret L., Thwarted Ambitions: Six Learned Women of the Italian Renaissance, in Soundings: An Interdisciplinary Journal, Penn State University Press Fall 1976, Vol. 59, No. 3 (Fall 1976), pp. 280-304.

King, Margaret L., “Book-lined Cells: Women and Humanism in the Early Renaissance “in Patricia Labalme, ed. Beyond their Sex, Learned Women of the European Past, New York, 1980) 66-90, esp. 77.

Levati, Ambrogio, “Cassandra Fedele”, in Dizionario Biografico Cronologico delle Donne Illustri, Vol I, Milan, Bettoni, 1822, 149.

Mapello, Gianmaria (books edited by, (in chronological order of publication)

Petrus Mantuanus: Logica. Add: Apollinaris Offredus: De primo et ultimo instanti ad defensionem communis opinionis adversus Petrum Mantuanum. Ed: Johannes Maria Mapellus. - Venezia : [Bonetus Locatellus], per Octavianus Scotus, 21 Apr. 1492

Andreae, Antonius, Scriptum in artem veterem Aristotelis et in divisiones Boethii. Ed: Johannes Maria Mapellus. Venice : [Bonetus Locatellus], for Octavianus Scotus, [after 3 Nov. 1492]

Petrus Mantuanus. Add: Apollinaris Offredus: De primo et ultimo instanti ad defensionem communis opinionis adversus Petrum Mantuanum. Ed: Johannes Maria Mapellus. Venice : Simon Bevilaqua, 1 Dec. 1492

Hentisberus, Gulielmus, De sensu composito et diviso. Add: Regulae solvendi sophismata; De tribus praedicamentis (Comm: Gaietanus de Thienis, Ricardus, Messinus, Angelus de Fossambruno, Bernardus Tornius). Sophismata (Comm: Gaietanus de Thienis). Simon de Lendenaria: Recollecta super Sophismatibus Hentisberi. Hentisberus: De veritate et falsitate propositionis; Probationes profundissimae conclusionum in regulis positarum. Ed: Joannes Maria Mapellus. Venice : Bonetus Locatellus, for Octavianus Scotus, 27 May 1494

Andreae, Antonius, Scriptum in artem veterem Aristotelis et in divisiones Boethii. Ed: Johannes Maria Mapellus. Venice : Otinus de Luna, Papiensis, 23 Nov. 1496.

Marcus, Hannah, “Cassandra Fedele and the Spectacle of Old Age in Early Modern Venice”, in Methuselah’s Children: The Renaissance Discovery of Old Age (in progress).

Niceron, Jean-Pierre, « Cassandra Fedele », Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire des hommes illustres dans la république des lettres, avec un catalogue raisonné de leurs ouvrages, Paris, 1729, vol VIII, 366-371.

Pappalardo, Francesco, ed., “Cassandra Fedele,” in Storie d’Ingegno e di coraggio: Profili di donne che Hanno Fatto l’Italia. Rome: Senato della Repubblica, 2025.

Pentolini, Abate Francesco, Le Donne Illustri Canti Dieci, Canto Secondo, Stanza 37, Livorno: Falorni, 1776, 142-143.

Petrettini, Maria, Vita di Cassandra Fedele. Venice, 1814 and 1852

Pignatti, Francesco. “Fedele, Cassandra”, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, 45, Rome, 1995, pp. 566-568.

Quadrio, Francesco Saverio, “Cassandra Fedele,” in Della storia e della ragione di ogni poesia, vol. 2, Milan, 1741, 208.

Radif, Ludovica, “La virale presenza del vir nel carteggio di Cassandra Fedele”, in Género y expresiones artísticas interculturales, ed. Eva María Moreno Lago, 2017,

Ravisius, Johannes (Ed.) : De memorabilibus et claris mulieribus: aliquot diversorum scriptorum opera. - Paris: Simon de Colines, 1521.

Riccoboni, Andrea, De Gymnasio Patavino, Padua, 1598, I, fol 19.

Robin, Diana. "Cassandra Fedele (1465-1558)." Italian Women Writers: A Bio-Bibliographical Sourcebook. Edited by Rinaldina Russell. Westport, Connecticut and London: Greenwood Press, 1994, pp. 119-27.

Robin, Diana, “Cassandra Fedele’s Epistolae (1488-1521): Biography as Ef-facement,” in The Rhetorics of Life-Writing in Early Modern Europe: Forms of Biography from Cassandra Fedele to Louis XIV, Thomas F. Mayer and D.R. Woolf (eds.), Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1995, 189.

Robin, Diana, “Cassandra Fedele (1465-1558)”, in Women Writing Latin From Roman Antiquity To Early Modern Europe, vol 3, Laurie J. Churchill, Phyllis R. Brown, and Jane E. Jeffrey (eds.), New York: Routledge, 2012.

Ross, Sarah G. “Her Father’s Daughter: Cassandra Fedele, Woman Humanist of the Venetian Republic”, in Anu Korhonen, Kate Lowe (eds.), The Trouble With Ribs: Women, Men and Gender in Early Modern Europe. Helsinki: Collegium Studies Across Disciplines in the Humanities and Social Sciences, 2007, pp. 204–222.

Ross, Sarah G., The Birth of Feminism: Woman as Intellect in Renaissance Italy and England, 2009.

Sansovino, Francesco, Venezia Città Nobilissima, Venice, 1581, Book I, 6, and Book XIII, 252.

Schlam, Carl C. "Cassandra Fidelis as a Latin Orator." Acta Conventus Neo-Latini Sanctandreani: Proceedings of the Fifth International Congress of Neo-Latin Studies (St. Andrews 24 August to 1 September 1982). Binghamton, N.Y.: Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, 1986, pp. 185-91.

Simonsfeld, Henry, “Zur Geschichte der Cassandra Fedele,“ in Studien zur Literatur-geschichte. Michael Bernays Gewidmet, Hamburg, 1893, 99-106.

Tomasini, Giacomo Filippo, Elogia virorum literis & sapientiai illustrium, Padua, Sardi, 1644, 343–358.

Tomasini, Giacomo Filippo, Gymnasium Patavinum. Padua, Schiratti, 1654

Worthen, Amy Namowitz, “Cassandra Fidelis, Veneta Literis Clarissima in Padua,” in Padua and Venice: Transcultural Exchange in the Early Modern Age, Brigit Blass-Simmen and Stefan Weppelmann, eds. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2017, 123-136.

Amy Namowitz Worthen, “Science, Devotion, and Poetry at the Servi. Fra Gasparino Borro di Venezia’s Lectures on Sacrobusto’s Sphæra mundi and His Triumphs of the Virgin,” in La chiesa di Santa Maria dei Servi e la comunità veneziana dei Servi di Maria (secoli XIV-XIX), Eveline Baseggio, Tiziana Franco, Luca Molà, eds. Rome: Viella, 2023

Comment

Your message was sent successfully