Birth

Baptized 24 February 1604.

Education

AutodidacticDeath

in the convent of Sant’Anna in Castello.

Religion

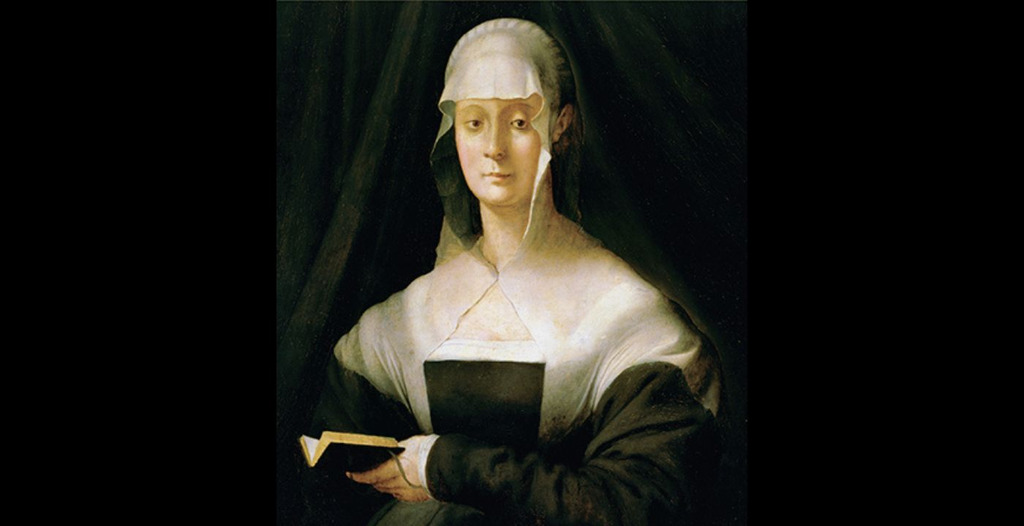

CatholicArcangela Tarabotti was a Venetian nun and writer. As a girl, she was consigned to the Benedictine convent of Sant’Anna, where she spent the remainder of her life after her 1629 consecration, despite her lack of religious vocation. Her true vocation was writing. In her lifetime, Tarabotti published five works, most of them polemical. Central to Tarabotti’s works are her assertion of women’s superiority and her denunciation of men’s injustice against them.

Tarabotti gained broad recognition for her ideas in her lifetime, not only in her home city of Venice but throughout Italy and into northern Europe, where she became well known for her expression of free thought. Though she was little studied in the 18th through mid-20th centuries, she is now recognized as an early advocate for women’s rights, an important dissident writer, and a political theorist of systems that oppress women.

Personal Information

Name(s)

Elena Cassandra [Arcangela] Tarabotti

Date and place of birth

Born Venice, 1604 in the sestiere of Castello. Baptized 24 February 1604.

Date and place of death

Venice, 1652, in the convent of Sant’Anna in Castello.

Family

Mother: Maria di Lorenzo Cadena, married 1599 to Stefano Tarabotti.

Father: Stefano Bernardino di Marc’Antonio Tarabotti, b. Venice 1574. Archival records show that Stefano was a chemist who worked with materials such as camphor, mercury, and lead.

Siblings: Tarabotti was the eldest daughter in a family of eleven children (four brothers and seven sisters, only five of whom survived to adulthood).

Marriage and Family Life

Consigned to the Benedictine convent of Sant’Anna as a girl (in either 1615, as Tarabotti writes, or 1617, according to an early biographer) despite a lack of religious vocation, Tarabotti was a monaca forzata, coerced into taking a nun’s vows. Tarabotti shared this fate with thousands of women throughout early modern Italy: many families saw the convent as an alternative to the rising cost of marriage dowries and as a solution to concerns about protecting the “honour” (chastity) of their female members and maintaining the integrity of the family patrimony.

The oldest of seven sisters, Tarabotti was the only daughter in her family to be cloistered at so young an age. Two of her sisters married; the other two, Angela and Caterina, remained unmarried and after the deaths of their parents ultimately sought shelter in the convent (Caterina in the same convent as Tarabotti, sometime after Tarabotti’s death in 1652). In her early manuscript, Inferno monacale (Convent Hell), Tarabotti bitterly laments the divergent fortunes of daughters destined for marriage – their lives filled with ease, luxury, and affection – and those fated for the penury and hardship of the convent.

Tarabotti’s sister Lorenzina (b. 1613) was married to Giacomo Pighetti, a writer and lawyer who was a member of the Accademia degli Incogniti, an influential Venetian literary society. This familial connection provided Tarabotti with an entrée to the literary world (see below).

Within the convent, Tarabotti had two close female friends. Regina Donà (Donati) was clothed as a nun at the same time as Tarabotti, in 1620, but died prematurely in 1645. Tarabotti wrote a memorial work praising her friend as the epitome of female religiosity, titled Le lagrime d’Arcangela Tarabotti per la morte dell’Illustrissima Signora Regina Donati (Tears of Arcangela Tarabotti Upon the Death of the Most Illustrious Signora Regina Donati). It was published together with a book of Tarabotti’s letters (Lettere familiari e di complimento [Letters Familiar and Formal], 1650), in which Tarabotti also wrote affectionately about Betta Polani (d. post-1645), a niece of Tarabotti’s convent sister Claudia Polani, and of Giovanni Polani, an Incongiti member who assisted with the publication of Tarabotti’s Paradiso monacale [Convent Paradise] in 1643. Betta left Sant’Anna in 1648 to marry, a departure that Tarabotti, as she wrote in her letters, found difficult to bear.

Education

Tarabotti was an autodidact. Though she would have received some rudimentary instruction in the convent so that she could read religious texts, she complains in her works about the poor quality of convent education, where young boarders (educande) and novices were taught by older nuns with barely more understanding than their own. From her own comments and from citations incorporated throughout her works, it is clear that Tarabotti read widely, and well beyond the bounds of accepted content for women religious. Not only does she demonstrate familiarity with the church fathers and a variety of saint’s lives and martyrologies, she also makes frequent reference to secular works by Ovid, Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio, and even Machiavelli, whose writings were placed on the Index of Forbidden Books by the Catholic Church in 1559. She intersperses Latin quotations into her works, and expresses both awareness of and frustration for the errors she makes due to the limits of her education. Tarabotti also notes that she cites many religious passages from memory, such as those found in the breviary, which was integral to a nun’s daily prayers.

Religion

A Benedictine nun, Tarabotti was Catholic and the circumstances of her life were shaped by the increasingly repressive cultural and religious climate of Counter-Reformation Italy. The outcomes of the Council of Trent (1545-1563) included the enforcement of strict enclosure for female monasteries, requiring women who professed vows to remain within the walls of the convent for the rest of their lives. This was a shift from previous eras when nuns were free to leave the convent for brief periods to visit family or work with the community, for example ministering to the sick. Tarabotti is blunt about the experience of forced enclosure, referring to it as a “prison” and as a “hell” from which the inhabitants could not hope to escape. Despite the polemic and often radical content of her works – Tarabotti flatly accuses both Church and State of complicity in the oppression of women – she seems to have escaped the notice of Church officials during her lifetime. Only after her death, in 1661, was one of her works – La Semplicità ingannata (Innocence Deceived), which condemned forced monachization – placed on the Index of Forbidden Books.

Transformation(s)

Tarabotti underwent several transformations in her life. The first of these were not voluntary – she was forced to become a nun and to follow along the path from investiture to profession to consecration, steps that were supposed to mark her spiritual progress but that Tarabotti instead resisted, as she reports in Paradiso. She recounts that she instead experienced a conversion through her meetings with the Cardinal Federico Corner (1579–1653), Patriarch of Venice; Corner may have helped Tarabotti to accept her vocation in part, but she never fully resigned herself to it. Corner, who had literary interests of his own, may also have encouraged Tarabotti in her literary vocation, which allowed the most important transformation in Tarabotti’s life. Writing became a lifeline for Tarabotti, providing her both a raison d’être and a means to disseminate her ideas. When her friend encouraged her to stop writing to preserve her health, Tarabotti responded “that I should leave off writing is quite impossible. In this prison and in my illness nothing else will satisfy me.” Over the course of her literary career, which stretched from the late 1630s until her death in 1652, Tarabotti transformed from a writer with largely local appeal to a writer known throughout Europe for her forceful advocacy for women and her forthright challenge to the church.

Contemporaneous Network(s)

Tarabotti was embedded in several influential networks that served her in various ways. Her efforts to circulate and publish her works were greatly aided by the support of the Venetian Accademia degli Incogniti, whose members included Giovan Francesco Loredano, an early champion of Tarabotti, as well as Tarabotti’s brother-in-law Giacomo Pighetti and Giovanni Polani, uncle of Tarabotti’s friend, Betta. Tarabotti was also in close contact with other Incogniti such as the playwright Pier Paolo Bissari and the librettist Givanni Francesco Busenello. The Augustianian friar Angelico Aprosio was an initial supporter of Tarabotti, though he later turned on her; Tarabotti’s epistolary friendship with Girolamo Brusoni, an apostate friar and writer, also soured due to her fears that he had usurped her literary territory by writing about forced monachization in his book, Amori tragici. Tarabotti also sought out powerful female patrons, corresponding briefly with Vittoria della Rovere of Florence, to whom she dedicated one of her works.

Also important to Tarabotti was the French diplomatic community in Venice. Through Henri Bretel de Grémonville, the French amabassador to Venice (whose daughters boarded in the convent of Sant’Anna), Tarabotti established connections to Cardinal Jules Mazzarin and his librarian, Gabriel Naudé, who visited her in the convent parlor. Tarabotti sought help from these contacts in her efforts to publish Tirannia paterna, which were unsuccessful during her lifetime. Tarabotti finally enlisted the help of the French humanist and astronomer Ismaēl Bouilliau in this effort, who sought a publisher for the book in Holland (where it eventually was published posthumously). The French community was also central to another of Tarabotti’s enterprises: the production and sale of the delicate lace for which Venetian nuns were famed. Tarabotti served as an intermediary between prospective buyers, such as the wife of the French ambassador, and the nuns who carried out the commissions, discussing designs with clients and negotiating rates and delivery dates.

Tarabotti corresponded with other women writers, including Guid’Ascania Orsi, a Bolognese nun and poet, and Aquila Barbara, a writer with whom Tarabotti exchanged literary advice. She clearly knew of the writer Lucrezia Marinella – the only other woman publishing as prolifically as Tarabotti in Venice at the time – and several poems by Marinella accompany Tarabotti’s first printed work, Convent Paradise. Interestingly, Marinella does not mention Tarabotti in any of her own works where she praises other Venetian women writers such as Moderata Fonte.

less

Significance

Works/Agency

In her lifetime, Tarabotti published five works, most of them polemical. She composed at least six others, four of which have been lost. Central to Tarabotti’s works are her assertion of women’s superiority and her denunciation of men’s injustice against them. Tarabotti likely began writing in the late 1630s. Her first work, Tirannia paterna (Paternal Tyranny), denounced the biological fathers and fathers of church and state who conspired to force young girls into convents despite their lack of religious vocation. Tarabotti circulated this work in manuscript form and spent two decades attempting to publish it. In Catholic cities from Venice and Florence to Rome and Paris, it was considered too dangerous to publish because of its challenge to monastic practice and church authority. Despite her tireless work to find a willing publisher, Tarabotti died before the work was put to press. But soon after her death her efforts finally bore fruit, and the book was published posthumously in Protestant Leiden in 1654, under the pseudonym Galerana Baratotti and with the less incendiary title Semplicità ingannata (Innocence Deceived). The work was placed on the Index of Forbidden Books in 1661.

Another early work of Tarabotti’s was even more controversial: Inferno monacale (Convent Hell) documented the scandalous behavior in convents that were filled with unwilling nuns. Tarabotti recognized that Inferno monacale, which focused on the consequences of the practice of forced monachization, rather than the causes, was even more controversial than Tirannia paterna. She did not seek to publish the work, but widely circulated it in manuscript form. At least one manuscript survived, and the work was published in 1990.

Tarabotti took a different tack in the first work she put to press, Paradiso monacale (Convent Paradise, 1643). In it, Tarabotti praised convent life, but only for willing nuns. In Tarabotti’s account, the deprivations and hardships of religious life brought only joy to the women religious who had voluntarily accepted the perpetual vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. Tarabotti celebrated the voluntary nuns’ spiritual connection with Jesus; the spiritual union they anticipated with their celestial bridegroom sustained the voluntary nuns through all earthly difficulties. Though some early critics saw Paradiso as a palinode to Tarabotti’s earlier works Tirannia paterna and especially Inferno monacale, Tarabotti here too clearly distinguishes voluntary and forced vocations, and condemns this latter practice. Paradiso also featured gender polemics that would become Tarabotti’s trademark: she celebrated women as God’s preferred creatures and condemned men’s arrogance.

Having focused on the convent milieu that she knew best in her first three works, Tarabotti catapulted herself into the secular world with her fourth work, and the second she published, L’Antisatira (The Antisatire, 1644). In the text, Tarabotti responded to a treatise entitled Contro ’l lusso donnesco satira menippea (Against Female Opulence, A Menippean Satire) by the Sienese writer Francesco Buoninsegni, which skewered women for what he characterized as their wastefulness, vanity, and vacuity. Tarabotti defended women’s right to luxury and instead mocked men for their own fashion excesses; she also engaged in a broader defense of women, including of women’s intellectual worth. She pointed out hypocrisy in the way women were treated: how they were prevented from studying but then attacked for their ignorance, for instance, or how they, but not men, were expected to be chaste.

Tarabotti’s next published work is her Lettere familiari e di complimento (Letters Familiar and Formal, 1650), a collection of 256 letters that showcased the nun’s wide-ranging literary and social network. The work was a remarkable literary achievement for a nun, especially since women religious in Venice were officially prohibited from letter writing. The collection features letters to powerful figures in Venice and beyond, including, for instance, letters to current and future doges, a future pope, and the grand duchess of Tuscany. More numerous still are Tarabotti’s letters to important contemporary writers, many of whom were members of the Accademia degli Incogniti, a Venetian literary academy that gathered the most important male writers in mid-seventeenth-century Italy. Tarabotti also corresponded with women writers, with whom she lamented the hostilities they faced from their male colleagues. Tarabotti’s Lettere were not mere transcriptions of the letters she wrote, even if there is proof that she exchanged letters with many of the correspondents who are featured in the collection. The work offers instead a carefully crafted, pixelated self-portrait of the writer, shown in action to be an indefatigable advocate for women in both private and public matters.

Along with the Lettere, Tarabotti published a memorial work on the death of her closest convent friend. The work is entitled Le lagrime d’Arcangela Tarabotti per la morte dell’Illustrissima Signora Regina Donati (Tears of Arcangela Tarabotti Upon the Death of the Most Illustrious Signora Regina Donati, 1650). The work celebrates Regina Donà as the embodiment of an ideal female monasticism. Indeed, Tarabotti depicts Donà in perfect consonance with her religious vocation, exhibiting an almost saintly acceptance of her earthly trials. Tarabotti uses this devotional work to justify the publication of the Lettere, to which the Lagrime are appended.

The final work that Tarabotti published in her lifetime was Che le donne siano della spezie degli uomini (That Women Are of the Same Species as Men, 1651). The text responded to a misogynous treatise originally published anonymously in Latin titled Disputatio nova contra mulieres, qua probatur eas homines non esse (New Disputation against Women in Which It Is Proved That They Are Not Human). That treatise had been translated into Italian and published (with false publishing information) in Venice in 1647 under the title Che le donne non siano della spezie degli uomini: Discorso piacevole, tradotto da Orazio Plato romano [That Women Are Not of the Same Species as Men: An Entertaining Discussion Translated by the Roman Orazio Plato], a work that attracted the Inquisition’s attention because of its heretical assertion that women had no souls and could not be saved. On the surface, the Disputatio maintained that the true target of its attack was the Anabaptists, and that its sophistical proofs that seemed to demean women were only meant to show that the Anabaptists flawed style of reasoning could lead to even the most absurd conclusion (that is, that women do not have souls). Tarabotti was loath to accept that the attack on women was mere rhetoric; she instead understood that no metaphor is innocent and that the decision to question women’s humanity as a “joke” was intimately related to the subjugation of women in the broader society. Driven by fury at the author’s debased portrayal of women, Tarabotti responded point by point to the treatise, upholding women’s spiritual and social worth while decrying the author’s flawed reasoning and lack of moral grounding.

In her Lettere, Tarabotti reported writing many other works that have since been lost. Her Purgatorio delle malmaritate (Purgatory of Unhappily Married Women) completed – together with Inferno and Paradiso – a sort of Dantean trilogy on women’s lives. Tarabotti also named a series of devotional works she wrote that – together with Paradiso and Le lagrime – would have formed a significant portion of her oeuvre: Contemplazioni dell’anima amante (Contemplations of the Loving Soul), La via lastricata per andare al cielo (The Paved Road to Heaven), and Luce monacale (Convent Light).

Reputation

Tarabotti gained broad recognition for her ideas in her lifetime, not only in her home city of Venice but throughout Italy and into northern Europe, where she became well known for the free thought she so fearlessly expressed. (The condemnation and placement on the Index of her Semplicità ingannata in 1661 provides implicit acknowledgement of the reach and danger of her ideas). Tarabotti was little studied in the eighteenth through mid-twentieth centuries. An important, if paternalistic biography of the nun, published by Emilio Zanette in 1960, brought her back into the public eye; from the 1990s onward, studies on the nun have proliferated. She is now recognized as an early advocate for women’s rights, an important dissident writer, and a political theorist of systems that oppress women.

Legacy and Influence

Despite the fame Tarabotti briefly attained in Venice during her lifetime, she remained a largely unknown and unstudied figure until the mid-twentieth century, when the first biography of her appeared, followed by critical studies. To date, three of Tarabotti’s works have appeared in modern Italian editions and five have been or are slated to be translated into English. Tarabotti’s former convent in the Castello neighborhood of Venice was transformed first into a military hospital and, more recently, into housing; there is no marker today to indicate that she lived and wrote there for some thirty-five years.

less

Controversies

Controversy

In her first published work, Paradiso monacale, Tarabotti included panegyric compositions from many important contemporary writers, and the work earned her many admirers. But when she published the Antisatira the next year, which pilloried men for their vanity and hypocrisy, much of the praise she had earned evaporated; important writers she had earlier counted as friends turned on her and accused her of plagiarism, charging that the style of Paradiso and the Antisatira were two different to have been written by the same pen. Tarabotti mocked these claims in her Lettere, where she defended her authorship and depicted the charges against her as deriving from the arrogance of male writers. She wrote to a fellow woman writer that “men obstinately do not want to admit that women know how to write without their help.”

Some early literary critics wrote romanticized and paternalistic accounts of the writer that were often as unreliable in their facts as they were in their approach. Modern critics have concurred in recognizing the genius of Tarabotti, who from her marginalized position in perpetual enclosure understood the social and political mechanisms that undergirded the practice of forced monachization and women’s more general subjugation. Studies have examined the convent environment in which Tarabotti lived and have illuminated both the literary value and historical importance of her works, while also showing her key role as a cultural intermediary. Critics differ on the role that the convent played in Tarabotti’s life: did it provide her a space in which – since she was free from the burdens of reproduction and childrearing – she was able to actualize herself? or do we instead need to foreground Tarabotti’s own depiction of the convent that – even if it provided her both the time and the knowledge that allowed her to write her works – she experienced as a hell on earth?

less

Bibliography

Primary (selected):

Tarabotti, Arcangela. Antisatira. In Francesco Buoninsegni and Arcangela Tarabotti, Satira e Antisatira, 67–227. Venice: Francesco Valvasense, 1644.

__________. Antisatira. In Francesco Buoninsegni and Arcangela Tarabotti, Satira e Antisatira, edited by Elissa Weaver, 56–105. Rome: Salerno, 1998.

__________. Antisatire. Edited and translated by Elissa Weaver. Toronto: Iter Press and the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2019.

__________. [Galerana Barcitotti, pseud.] Che le donne siano della spetie degli huomini. Difesa delle donne, di Galerana Barcitotti, contra Horatio Plato. Nuremberg [Venice]: Iuvann Cherchenbergher, 1651.

__________. Che le donne siano della spezie degli uomini: Women Are No Less Rational Than Men. Edited by Letizia Panizza. London: Institute of Romance Studies, 1994.

__________. Convent Paradise. Edited and translated by Meredith K. Ray and Lynn Lara Westwater. Toronto: Iter Press and the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2019.

__________. L’Inferno monacale di Arcangela Tarabotti. Edited by Francesca Medioli. Turin: Rosenberg & Sellier, 1990.

__________. Le lagrime d’Arcangela Tarabotti per la morte dell’Illustrissima Signora Regina Donati. Venice: Guerigli, 1650.

__________. Lettere familiari e di complimento. Venice: Guerigli, 1650.

__________. Lettere familiari e di complimento. Edited by Meredith K. Ray and Lynn Lara Westwater. Turin: Rosenberg & Sellier, 2005.

__________. Letters Familiar and Formal. Translated and edited by Meredith K. Ray and Lynn Lara Westwater. Toronto: Iter Inc. and Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, 2012.

__________. Paradiso monacale. Libri tre. Con un soliloqio a Dio. Venice: Guglielmo Oddoni, 1663 [1643]. Private collection.

__________. Paternal Tyranny. Translated and edited by Letizia Panizza. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

__________. [Galerana Baratotti, pseud.]. La semplicità ingannata. Leiden: Giovanni Sambix [Daniel Elsevier], 1654.

__________. La semplicità ingannata. Edited by Simona Bortot. Padua: Il Poligrafo, 2007.

__________. Women are of the Human Species: A Defense of Women. In “Women are Not Human”: An Anonymous Treatise and Its Responses, translated and edited by Theresa Kenney, 89–159. New York: Crossroad, 1998.

Archival resources (selected):

Venice, Archivio di Stato

Cong. Rel. sopp, Sant’Anna di Castello, busta 5, 15, 17

Web resources (selected):

https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/efts/IWW/BIOS/A0048.html

https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780195399301/obo-9780195399301-0328.xml

Issues with the sources.

Primary sources:

Historically, it was difficult to access Tarabotti’s writings because they were either unpublished or available only in hard-to-find early modern editions. This is no longer the case because of the numerous critical editions of her works that have been issued in the last 30 years. Many of the original early modern texts are now also available in digitized versions online.

Secondary sources:

Tarabotti has been widely studied in both Italian and Anglo-American contexts, in studies that feature careful archival research, in-depth historical analysis, and subtle literary critique. Anglo-American scholarship in general takes into account scholarship produced both in English and Italian. Some Italian scholarship, by contrast, overlooks studies not published in Italy, thereby limiting the scholarship’s scope.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully