Birth

Anna was born sometime in the 1020s, either in Kyiv (Kiev) or Novgorod.

Education

Anna very likely received some formal education. As a literate woman, Anna would have been remarkably well-educated for the eleventh century.

Death

Her place of death and burial remains unknown.

Religion

Latin ChristianityAnna Yaroslavna (Anna de Kiev) was a princess of Kievan Rus' who became Queen of France when she married King Henri I in 1051.

Following her first husband Henri’s death in 1060, Anna ruled France as part of the regency council with her brother-in-law on behalf of her son Philippe I until his majority in 1067. During her reign, Anna patronized a number of churches and monasteries in France, such as the abbeys of Saint-Maur-des-Fossés and Saint-Martin-des-Champs. In the 1060s, she re-founded the Abbey of Saint-Vincent in the royal city of Senlis, restoring it from ruin after Viking invasions. Her Cyrillic signature on the charter for the Abbey of Saint-Crépin-le-Grand around 1063 is the only known example of a Capetian queen’s signature on parchment and the only known signature of a member of the ruling clan of Rus'.

Personal Information

Name(s)

Anna Yaroslavna; Anna of Kyiv (Kiev) (known in French historiography as Anne de Kiev).

Date and place of birth

Anna was born sometime in the 1020s, either in Kyiv (Kiev) or Novgorod.

Date and place of death

The Abbey of Saint-Vincent in Senlis which Anna re-founded from ruin in the 1060s, celebrated an annual obit (memorial service) for Anna on 5 September until the French Revolution. Based on the dating of the last surviving charter to which Anna subscribed (1075) and the dating of a donation charter made by her eldest son Philippe I in 1079 for the soul of his parents as well as the date of the obit, Anna must have died on 5 September, between 1075 and 1079.

In an article published on 22 June 1682 in the Journal des Savants, the Jesuit Claude-François Menestrier claimed to have discovered Anna’s tomb in the Abbey of Villiers, forty kilometres from Paris, in the town of Serni (Department of Essonne). He alleged that the inscription on the tomb read, “Here lies the lady Agnes, once the wife of King Henri.” An earlier description of the tomb noted by one Magdelon Theulier in 1642 refutes this theory, however, by proving that the key words “quae fuit uxor Henrici” (“who was the wife of Henri”) were added at some subsequent point after Theulier’s description in this year. Thus, the tomb never contained the inscription (“Hic jacet domina Agnes, uxor quondam Henrici regis”) claimed by Menestrier that would identify this tomb with Anna’s.

One medieval chronicle, the early twelfth-century Historia Franciae, states that Anna Yaroslavna returned alone to Rus’ after the death of her second husband, Count Raoul of Crépy-en-Valois (d. 1074).

Her place of death and burial therefore remains unknown.

Family

Mother: Anna’s mother was Princess Ingigerd-Irene of Sweden (d. 1050), the daughter of King Olof Eriksson Skötkonung (r. 995-1021/1022) and a captive Oborite woman named Estrid.

Father: Anna’s father was Prince Yaroslav the Wise (d. 1054) of Rus’, the son of Prince Vladimir (or Volodimir) Sviatoslavich (d. 1015) and a Scandinavian woman, Rogned / Rogneda (or Ragnheid, d. 1000). Vladimir repudiated Rogned upon his conversion to Byzantine Christianity in 988/989 as well as upon marriage with the Byzantine princess Anna Porphyrogenita (d. 1011?), the sister of the Emperor Basil II (r. 976-1025). Yaroslav succeded to the throne in 1019, the year of his marriage to the Swedish princess Ingigerd, after a bloody succession struggle with his brothers following the death of Vladimir. Yaroslav became sole ruler of Rus’ in 1035/1036 following the death of his brother Mstislav.

Marriage and Family Life

Anna married King Henri (Henry) I of France in 1051 and had three sons with him: Philippe (Philip; b. 1052; d. 1108), Hugues (Hugh; b. 1053; d. 1101), and Robert (b. 1053, d. shortly after 1053). After Henri’s death in 1060, Anna took as her second husband Count Raoul de Crépy-en-Valois (d. 1074). The precise date of Anna’s marriage to her second husband is not known, but occurred in 1061.

Anna’s sisters also became notable queen-consorts of medieval Europe: her sister Anastasia Yaroslavna (d. after 1074) married King Ándrás I (Andrew) of Hungary (d. 1060), while her sister Elizabeth Yaroslavna (d. after 1066) married King Harald Sigurdsson Hardrada of Norway (d. 1066).

Many of Anna’s brothers also married royal and noble brides. Her brother Iziaslav Yaroslavich (d. 1078) married Princess Gertruda of Poland (d. c. 1108?), her brother Sviatoslav Yaroslavich (d. 1076) took as his second wife the German noblewoman Oda of Stade (d. after 1076), and her brother Vsevolod (d. 1093) married a Byzantine princess of unknown name (d. 1067), of the house of Monomachos. Vsevolod’s daughter by a second wife, Eupraxia Vsevolodovna (d. 1109), became the second wife of Emperor Henry IV of Germany (d. 1106).

Anna Yaroslavna may also have had a third sister, Agatha (or Agafia), whose genealogy is, however, highly debated. She married the Anglo-Saxon Prince Edward the Exile of England (d. 1057), the son of King Edmund Ironside (d. 1016). Following the Norman invasion of England in 1066, Agatha/Agafia fled with her children to Scotland in 1067 or 1068 where they were received by King Malcom Macduncan III Canmore of Scotland (r. 1058-1093). Agatha/Agafia’s daughter, Margaret (d. 1093) married King Malcom and became revered as one of Scotland’s national saints.

Education

Anna very likely received some formal education. Her literacy is suggested by the fact that her signature appears in Cyrillic script on a charter from the 1060s (probably 1063) in favour of the Abbey of Saint-Crépin-le-Grand in Soissons. In this charter, Anna signs as “AHA РЪИНА” (“Ana reina”, i.e. “Anna regina,” “Anna, the Queen”). As a literate woman, Anna would have been remarkably well-educated for the eleventh century.

Religion

Anna was raised as an Orthodox Christian, but adjusted to Latin Christianity (medieval Roman Catholicism) following her marriage.

Transformation(s)

Anna’s coronation ceremony in Reims Cathedral in 1051 elevated her to the position of consort, a sharer in royal dignity. Anna successfully adapted herself to the roles and expectations of a queen-consort in France, holding the throne on behalf of her son Philippe I and ensuring his succession after her first husband Henri’s death.

Contemporaneous Network(s)

As queen-consort and then queen-mother, Anna was at the centre of French royal power. Her sisters, as noted above, also became queens.

less

Significance

Works/Agency

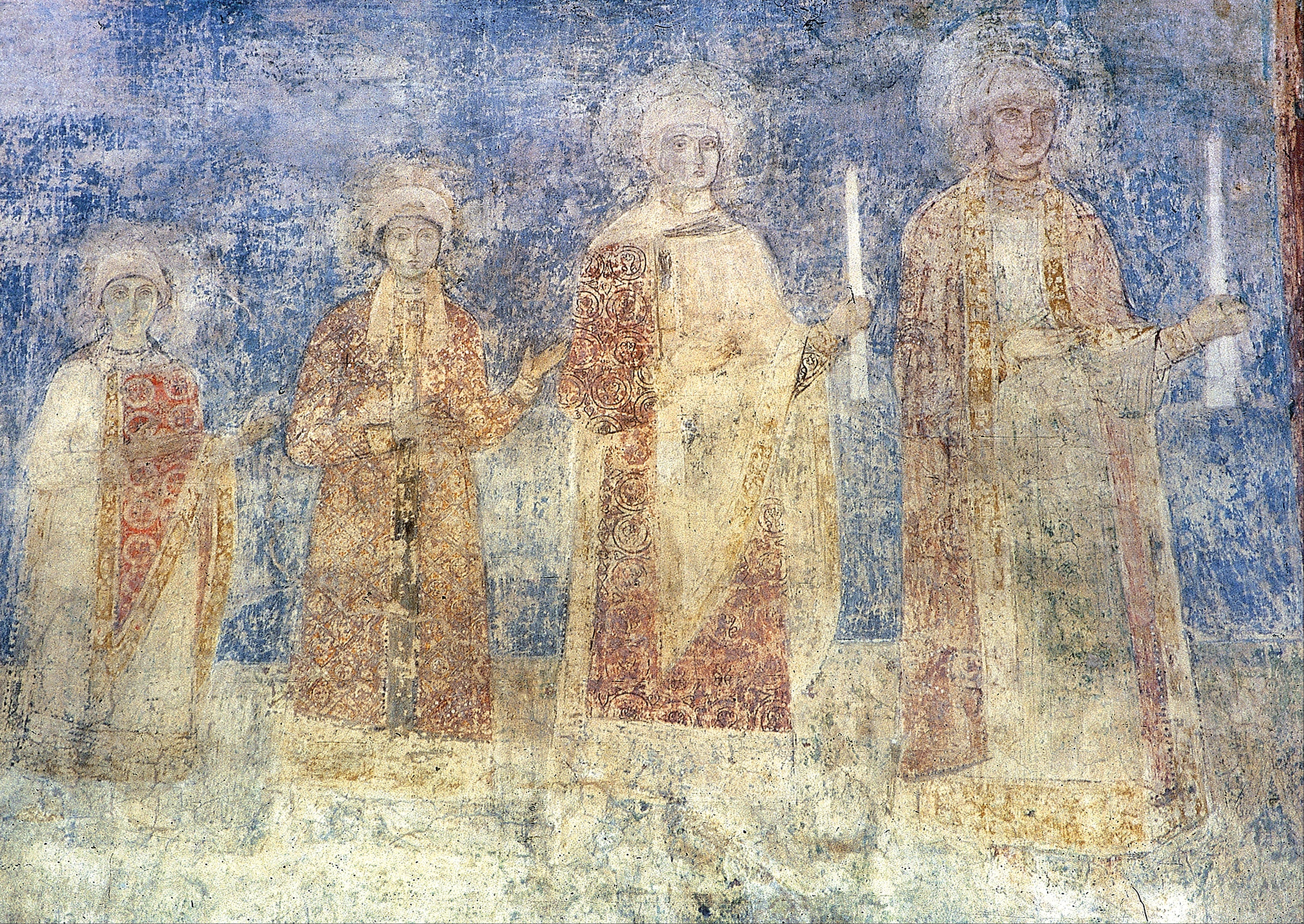

No Rus’ source records Anna’s presence. However, the donors’ fresco in the nave of Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv, painted around 1045/1046, depicts four or five members of Yaroslav the Wise’s family. These may well represent Anna and her sisters, or sisters and mother.

In 1051, Anna became the first French queen to be crowned in Reims Cathedral. It is also likely that she was responsible for introducing the name “Philippe” (Philip) into the French royal dynasty. In an age of high infant mortality, children’s names among royal and noble families rarely changed; they became markers of belonging to a certain dynasty. Thus Anna and Henri named their second son Robert, after Henri’s father and brother and their third son Hugues (Hugh), after Henri’s grandfather. Prior to 1052 when Philippe was born, the name was hardly known in France. Among the inspirations for the name which the scholar Jean Dunbabin suggests is the Apostle Philip, who was said to have converted the Scythians. French sources identified Rus’ with ancient Scythia; the name thus perhaps stressed connections between Rus’ and France.

Following her first husband Henri’s death in 1060, Anna ruled France as part of the regency council with her brother-in-law, Count Baldwin V of Flanders, on behalf of her son Philippe I until his majority in 1067.

During her reign, Anna patronized a number of churches and monasteries in France, such as the abbeys of Saint-Maur-des-Fossés and Saint-Martin-des-Champs. In the 1060s, she re-founded the Abbey of Saint-Vincent in the royal city of Senlis, restoring it from ruin after Viking invasions. This abbey still survives today and currently houses a private school, the Lycée Saint- Vincent (http://www.lycee-stvincent.fr). Anna’s patronage was praised by no less a person than Pope Nicholas II (r. 1059-1061) in a letter he sent in 1059 or 1060.

Her Cyrillic signature on the charter for the Abbey of Saint-Crépin-le-Grand around 1063 is the only known example of a Capetian queen’s signature on parchment and the only known signature of a member of the ruling clan of Rus’.

Abbot Suger in his twelfth-century The Deeds of Louis the Fat, written about Anna’s grandson, mentions that this French king donated to the Abbey of Saint-Denis a red gem that had belonged to Anna. This gem was so precious that it was used to enclose one of the most important relics belonging to the Abbey, a thorn allegedly from the Crown of Thorns worn by Christ at the crucifixion.

Reputation

Contemporary French chronicles record Anna’s marriage without much comment or surprise, although one text, the Annals of Vendôme, calls her a “Scythian” queen, identifying her Rus’ origins with an ancient Eurasian people first discussed by the Greek historian Herodotus (d. c. 420s B.C. E.) The general silence of French chronicles should not be interpreted to mean, however, that Anna’s marriage to Henri was seen as unimportant. Documentary evidence from royal charters show that Anna was politically active, especially in the first year of her son’s minority (1060-1061).

Anna’s reputation was dealt a blow upon her second marriage in 1061with Raoul, Count of Crépy-en-Valois. The marriage was condemned by French clerics because it was bigamous: Raoul had repudiated his wife Aliénor in order to marry Anna. Despite the scandal, however, Anna was not permanently excluded from the royal court, and remained active as queen until Philippe’s own first marriage in 1072 to Berthe of Holland (repudiated in 1092).

Legacy and Influence

Though little has been written on Anna in English scholarship, she has fascinated Russian, Ukrainian, and Soviet historians and popular writers for centuries.

In the alliance between France and the Russian Empire in 1891, Anna Yaroslavna was cited as a symbol of Franco-Russian friendship and when Tsar Nicholas II visited Paris in October 1896 he received a facsimile copy of the charter of Soissons containing Anna’s signature. In the Soviet period, Russian interest in Anna continued. For example, in 1978, Anna’s betrothal and journey to France was the subject of a Soviet film directed by Igor Maslennikov, titled Yaroslavna- Koroleva Frantsii (Yaroslavna, Queen of France).

From the early twentieth century onwards, Anna has also been claimed as part of Ukraine’s heritage, in particular to stress Ukraine’s ties with and aspirations to become part of the Western European community. For instance, Anna was the subject of a Ukrainian opera, titled Anna Yaroslavna, that premiered in Carnegie Hall in 1969 (libretto by Leonid Poltava, music by Antin Rudnitz’kyi). She has been featured on Ukrainian stamps, and has a French language school in Kyiv named after her, the Lycée Français Anne de Kiev (http://lyceeadk.com/). More recently, her life formed the subject of Ukrainian television biopics, the most recent in 2019.

In 2005, a new monument to Anna Yaroslavna was unveiled in the Place des Arènes, Senlis, by father and son sculptor team, Mykola and Valentyn Znoba. An older monument to Anna also stands within the walls of Saint-Vincent de Senlis, which commemorates her foundation of this institution. A children’s preschool (École Maternelle Anne de Kiev) and cultural institute (https://www.facebook.com/AnnedeKyiv/) are named after her in Senlis.

Current Identification(s)

Anna Yaroslavna’s life is included in surveys of Rus’ “foreign relations,” in genealogies of the Capetian dynasty of France, and in works on French queens. Her life has been referenced in works examining French queens by authors such as Marion Facinger, Robert-Henri Bautier, Philippe Delorme, and Emily Ward, as well as by those studying medieval French-Rus’ ties such as Roger Hallu, Wladimir Bogomoletz, Christian Raffensperger, Vladimir Vladimirovich Shishkin, Alexander Musin, and Talia Zajac.

less

Controversies

Controversy

In Anna’s own lifetime, her second marriage to Count Raoul caused a scandal, because Raoul was already married at the time. Anna was able to recover her position, however, and there is no direct evidence that she was excommunicated or permanently excluded from the French royal court, as has been previously suggested in older scholarly literature.

With respect to foreign relations, Anna’s legacy has become a focal point of tensions between Russia and Ukraine, as each have claimed her as their own. In May 2017, following President Vladimir Putin’s state visit to France in which he referred to Anna Yaroslavna by an affectionate nickname as “Russian Ani,” the Ukrainian embassy formulated an official protest. Conflicting claims to the legacy and heritage of Rus’ in general and Anna Yaroslavna in particular continues in the Russian and Ukrainian popular press and in diplomatic relations.

less

Bibliography

Primary (selected)

Caix de Saint-Aymour, Amédée, Comte de. Anne de Russie, Reine de France, et Comtesse de Valois au XIe siècle. 2nd ed. Paris: Honoré Champion, 1896. < https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k852030d>

Pseudo-Clarius, Chronique de Saint-Pierre-le-Vif de Sens, dite de Clarius: Chronicon Sancti Petri Vivi senonensis, ed., trans., and annotated Robert-Henri Bautier and Monique Gilles, with the collaboration of Anne-Marie Bautier (Paris: Centre national de la recherche scientifique, 1979).

Recueil des actes de Philippe Ier roi de France (1059-1108), ed. Maurice Prou (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1908).

Recueil de chartes et documents de Saint-Martin-des-Champs: monastère parisien, ed. Joseph Depoin, Vol. 1, Archives de la France monastique, vol. 13 (Paris: Jouve, 1912).

Recueil des Historiens des Gaules et de la France, vol. 11: contentant principalement ce qui s’est passé sous le règne de Henri Premier, fils du Roi Robert le Pieux, c’est-à-dire, depuis l’ans MXXXI, jusqu’à l’ans MLX par les religieux bénédictins de la Congrégation de Saint-Maur, rev. ed. Léopold Delisle (Paris: Victor Palmé, 1876).

Recueil des pièces historiques sur la reine Anne ou Agnès, épouse de Henri Ier, Roi de France et fille de Iarosslaf Ier, grand duc de Russie, ed. A. Labanoff de Rostoff (Paris: Firmin Didot, 1825).

Soehnée, Frédéric. Catalogue des Actes d’Henri Ier Roi de France (Paris: Honoré Champion, 1907).

Archival resources (selected):

Amiens

Cartulaire I, Archives départementales de la Somme 4 G 2966.

Beauvais

Archives départementales de l’Oise, H 946, 18 and 169.

Blois

Archives départementales du Loir-et-Cher, 16 H 113.

Archives départementales du Loir-et-Cher, fonds de Pontlevoy, 17 H 1, no. 2.

Chartres

Archives départementales d’Eure-et-Loir H 399.

London

British Library, Add. MS. 11662.

Paris

Archives nationales de France, AE II 101; formerly K 19 no. 5/2.

Archives nationales de France, K 20, no. 1.

Archives nationales de France, K 20, no. 2.

Archives nationales de France, LL 46 (formerly LL 112), Livre noir of Saint-Maur-des-Fossés.

Archives nationales de France LL 1156.

Archives nationales de France, LL 1157.

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Collection Baluze, vol. 47.

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Collection Clairambault, vol. 1225 (formerly Mélanges 115).

Biblothèque nationale de France, ms. Lat. 10977.

Bibliothèque nationale de France, ms. Lat. 12878

Bibliothèque nationale de France, ms. Lat. 5441

Bibliothèque nationale de France, ms. Picardie, vol. 294, no. 38.

Reims

Bibliothèque Carnegie de Reims, ms. 85.

Web resources (selected):

“Anne of Kiev,” in Epistolae. Medieval Women’s Latin Letters, trans. Joan Ferrante et al.

“Lycée Français Anne de Kiev.” < http://lyceeadk.com/> (Website of Ukrainian school named after Anna).

Maslennikov, Igor, dir. Yaroslavna- Koroleva Frantsii, 1978. Lenfilm Studio. Distributed online 19 February, 2018. < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qTMxsGDE8rY > [last access 31 August 2021] (Soviet fictional adventure film about Anna)

Raffensperger, Christian. “The Princess of Discord: Anna of Kyiv and Her Influence on Medieval France.” Krytyka. Thinking in Ukraine. June, 2017.

Rusian Genealogy Web Map. Compiled by Christian Raffensperger, with technical assistance by David J. Birnbaum. Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute (HURI), with technical support provided by HURI and the Center for Geographical Analysis at Harvard University.< http://gis.huri.harvard.edu/rusgen/> (Website with genealogical data on Anna’s family and map showing marriages of Rus’ women across Europe).

Sarycheva, Dar’ia, dir. “Taiemnytsi velykykh Ukraïntsiv. Anna Kyïvs’ka.” Telekanal 1+1. 2019. < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kG4mLdcpqwM> [last access 23 March 2021] (popular Ukrainian television biopic).

Ward, Emily Joan. “Anne of Kiev (c.1024–c.1075) and a Reassessment of Maternal Power in the Minority Kingship of Philip I of France.” In Historical Research 89.245 (Aug. 2016): 435-453. Open Access: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2281.12139 (article showing Anna’s important role as guardian of her son during his minority).

Zajac, Talia. “Gloriosa Regina or ‘Alien Queen’? Some Reconsiderations on Anna Yaroslavna’s Queenship (r. 1050-1075).” In Royal Studies Journal 3.1 (2016): 28-70. Open Access: < http://www.rsj.winchester.ac.uk/index.php/rsj/article/view/88>

(article arguing against the perception of Anna as an “exotic” queen, showing her successful adaptation to the role of queen-consort and queen-regent in France).

Comment

Your message was sent successfully