Birth

c. 401, Athens

Death

460, Jerusalem

Aelia Eudocia Augusta was a fifth-century Byzantine empress and poet who transformed from an Athenian philosopher's daughter into a pioneering Christian literary figure. Born around 401 as Athenaïs, she converted to Christianity and married Emperor Theodosius II in 421. Eudocia revolutionized Christian literature by creating the first complete Christian Homeric cento—2,400 lines retelling biblical stories using Homer's verses—establishing herself as a cultural bridge between classical and Christian traditions. Her works included hagiographical poetry and biblical paraphrases that blended classical Greek literary forms with Christian theology. Beyond literature, she was a significant patron of public works, churches, and charitable programs in Antioch and Jerusalem. Though subjected to court intrigue and accusations that modern scholars recognize as politically motivated fiction, Eudocia wielded substantial religious and cultural authority throughout the Christian East.

Personal Information

Name(s)

Aelia Eudocia Augusta (Greek: Αἰλία Εὐδοκία Αὐγούστα); born Athenaïs

Date and Place of Birth

c. 401, Athens

Date and Place of Death

460, Jerusalem

Family

Father: Leontius, a noted pagan philosopher and rhetorician of Athens

Mother: Name unknown

Marriage: Married to Emperor Theodosius II (r. 408–450 CE) in 421 CE

Children: Two daughters. Licinia Eudoxia (422- c. 493) who became empress of the Western Roman Empire as wife of Valentinian III (m. 437); Flacilla (named after her great-grandmother) who died in 431. Evidence for a son (who, if he existed, died in infancy) is not compelling.

Aunts: Eudocia’s mother’s sister and her father’s sister were important to her; they looked after her when she was orphaned.

Brothers: Valerius and Gesius.

Education (short version)

Educated in Athens in classical Greek rhetorical tradition, with training in philosophy, poetry, and rhetoric.

Education (longer version)

Eudocia’s early education, under her father’s direction, was steeped in the traditional Greco-Roman paideia. She mastered Homer, the tragedians, philosophy, and rhetoric, skills which later informed her Christian literary works. Her expertise with Homer was impressive: she adapted the epic poet’s diction and hexameter to Christian themes, creating works that blended classical literary authority with Christian theology.

Religion

Raised in the pagan traditions of late antique Athens, she converted to Christianity before her marriage to the Roman emperor Theodosius II, taking the baptismal name Aelia Eudocia (a variation of the Greek name of her mother-in-law, Aelia Eudoxia). Her poetry reflects a synthesis of Christian devotion with the language and forms of classical Greek literature.

Transformation(s)

Eudocia transformed from an Athenian philosopher’s daughter into a Christian empress, and from a student of pagan classics into a poet of Christian epic. Her literary career represents an act of cultural mediation: she retooled Homeric verse to tell biblical and hagiographical stories, asserting a female authorial voice in both imperial and theological domains.

Contemporaneous Network(s)

Eudocia’s position within the imperial court afforded her close ties to influential ecclesiastical and political figures, including Cyril of Alexandria, who corresponded with her directly. She was actively engaged in the theological debates that shaped Constantinople’s religious landscape. Even after her departure from the court, Eudocia sustained a vibrant network in Jerusalem, forging connections with monastic leaders, bishops, and pilgrims. Among her most notable relationships was her reported friendship with Melania the Younger, a revered ascetic who was later canonized—an association that further underscores Eudocia’s deep integration into the spiritual and intellectual life of the Christian East.

less

Significance

Works / Agency

Written Works:

- Homeric Cento (Homeric Verses on the Life of Christ). This is a biblical epic composed entirely of verses from Homer, rearranged to narrate the Christian story from Genesis to the Resurrection. This cento repurposes the prestige of Homer for Christian theology, making Eudocia a cultural bridge between classical and Christian traditions. Eudocia’s cento comprises 2,400 lines of verse and survives complete. This work demonstrates her mastery of Homeric language and her ability to weave a coherent Christian narrative out of inherited pagan verse.

- Martyrdom of St Cyprian (Cyprian and Justa). This is a hexameter poem retelling the story of the conversion and martyrdom of Cyprian, a pagan magician turned Christian bishop, and the steadfast faith of the virgin Justa. The work emphasizes divine triumph over pagan magic, resonating with Eudocia’s own life story. It does not survive complete: about 800 lines are extant, along with a paraphrase by Photius. The poem highlights Eudocia’s engagement with hagiography and the Christian moral ideal of steadfastness under persecution.

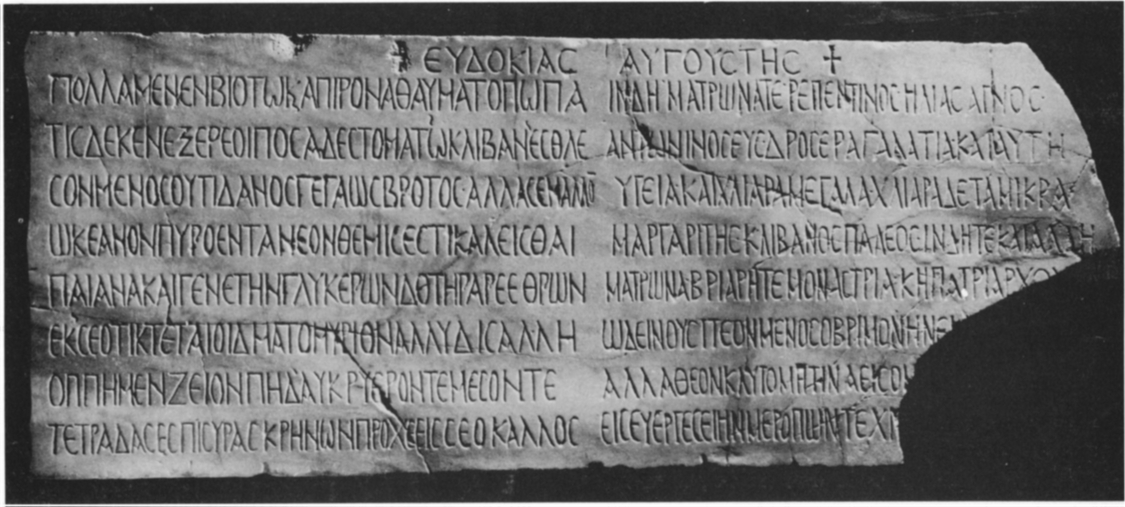

- Poem on the Baths at Hamat Gadar (Ancient Greek city of Gadara). A descriptive poem in hexameters praising the beauty and qualities of the springs that feed the baths. This gives a rare example of Eudocia’s occasional poetry; the work was inscribed on a plaque found in situ in the archaeological remains of the baths.

- Other Known Works which have not survived

- A poem on the Roman victories of her husband over the Persians in 421 and 422.

- A verse paraphrase of the Octateuch (the first eight books of the Old Testament).

- A paraphrase of the books of the prophets Zechariah and Daniel.

- An encomium in praise of Antioch, delivered there in 438 (one line of this survives).

Other Works of Social and Cultural Significance

Building works and welfare:

Eudocia was far more than a literary figure; she was a prominent member of the imperial family whose legacy extended into public welfare and civic development. Celebrated for her independent acts of euergetism, Eudocia played a vital role in improving the lives of her subjects. In Antioch, she was credited with initiating a welfare program to provide food for the poor and financing major infrastructure projects, including the construction of a basilica, the restoration of a bath complex, and enhancements to the city’s fortifications. Her contributions to Jerusalem were equally significant: she commissioned the building of a basilica dedicated to St Stephen, where she enshrined some of his relics.

Religious relics:

Eudocia’s acquisition and veneration of sacred relics, such as the chains of St Peter and the bones of St Stephen, were notable achievements in the Christian world of her time, underscoring her spiritual devotion and political influence.

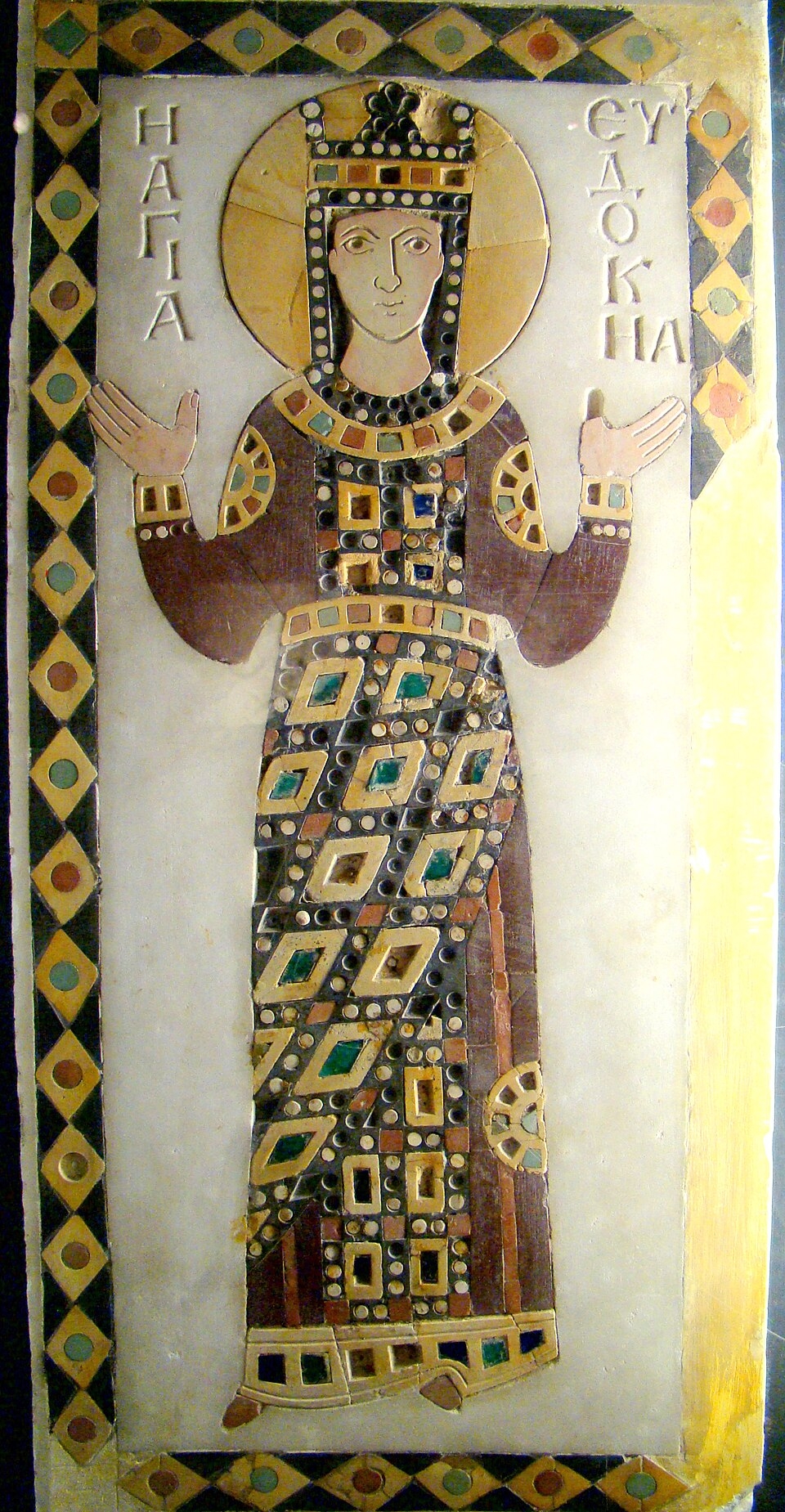

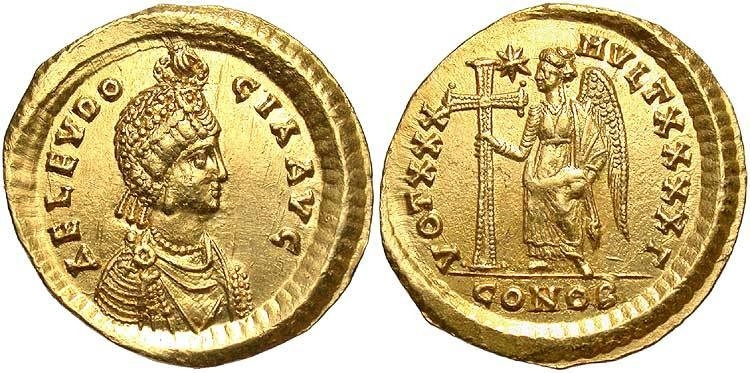

Contemporaneous Identifications

Contemporary sources depict Eudocia as an exemplar of classical learning in a Christian empire. Priscus and John Malalas recount her imperial activities, while the Chronicon Paschale notes her pilgrimage to Jerusalem and charitable works. She was recognized as Augusta and commemorated on coinage, projecting both imperial authority and literary identity. The city of Antioch honoured her by erecting two statues of her in important public buildings, one made of bronze and one of gold. She was later named a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Reputation

Eudocia’s reputation was mixed in her lifetime. She was praised for learning and piety, yet subject to accusations of political intrigue and adultery. These accusations have been seen as grounds for her withdrawal to Jerusalem. However, it is more likely that the accusations are later fictions, and she went to Jerusalem to pursue her work there: she was an active Christian patron of church construction, monasteries and other charities. Modern scholarship has reevaluated her as a key figure in the transmission and Christianisation of classical Greek literary forms.

Legacy and Influence

Her works were included in Byzantine anthologies and influenced later Christian poets using classical metres. The Homeric cento tradition continued in both Greek and Latin, and her blending of biblical narrative with epic style anticipates medieval Christian epics. Eudocia’s life and works demonstrate how a woman could claim literary authority within—and sometimes against—the political constraints of an imperial court and a patriarchal church.

less

Controversies

Controversies

The controversies surrounding Eudocia reveal far more about ancient anxieties toward powerful women than about her own conduct. When she left Constantinople for Jerusalem around 443 CE, ancient historians explained the move in ways that undermined her agency. Some claimed rivalry with Theodosius II’s sister Pulcheria; others spread rumours of an affair with Paulinus, the emperor’s close confidant. These stories—preserved in Malalas and later chroniclers—are now widely recognized as gossip, fiction, and folktale motifs rather than reliable biography. The famous anecdote of the exchanged apple, supposedly proving adultery, bears all the hallmarks of a narrative designed to question a woman’s sexual honour and destabilize imperial authority.

In antiquity, accusations of female sexual misconduct functioned as political weapons, used to discredit women and reassert male control. Roman history abounds with such examples: Cicero’s attack on Clodia (Pro Caelio 31), Tacitus’ scandalous depiction of Messalina (Annals 11.26), and the biblical story of Susanna (Dan. 13). Origen even notes slanders against Mary, the mother of Jesus (Against Celsus 1.28–32), showing how deeply entrenched this tactic was. Seen in this light, the charges against Eudocia reflect less her lived reality than a discursive strategy aimed at silencing her authority.

Equally revealing are the ‘Cinderella’-like motifs woven into her biography. Malalas reports that Eudocia boldly contested her inheritance, appealing directly to the imperial court; her courage impressed Pulcheria, who arranged her marriage to Theodosius. Later tales of Pulcheria’s jealousy reduce both women to caricatures of courtly rivals. As Julia Burman has shown, these stories rest on “stereotypical prejudgements about two strong women with a weak man,” rather than on credible evidence. Such traditions reveal not history, but the ways historiography itself worked to erode female authority in Constantinople.

Beyond these palace intrigues, Eudocia’s own actions present a different picture. She remained a politically engaged and theologically influential Christian leader. Even after leaving court, she played a central role in doctrinal debates, lending support to the Monophysite view that Christ’s nature was wholly divine. Her prominence was such that Pope Leo I addressed her directly in 453, urging her to defend orthodoxy. That the bishop of Rome sought her support speaks volumes about her standing in shaping theological discourse.

The “controversies” around Eudocia are thus less evidence of scandal than of the cultural mechanisms by which women’s power was reframed, distorted, or curtailed. She emerges not as a disgraced consort, but as an empress and poet who wielded religious, cultural, and intellectual authority in both Constantinople and Jerusalem.

New and Unfolding Interpretations

Recent scholarship has redefined our understanding of Eudocia’s later life and writings. Her move to Jerusalem, long cast as a fall from grace, appears instead as a continuation of influence through new forms of authority. There she reshaped her imperial role by sponsoring churches, monastic communities, and literary projects. Free from the demands of palace politics, she composed some of her most important works, including the Martyrdom of St Cyprian and the biblical paraphrases noted by Photius.

This was not a retreat into obscurity, but a deliberate reorientation of power. By relocating to Jerusalem, Eudocia entered a different sphere of influence, one grounded in pilgrimage, theology, and literary creation. She fashioned herself as a cultural mediator between the imperial centre and the Christian East. Her poetry, blending Homeric form with biblical narrative, can be read as a bold act of self-definition, establishing her as an authoritative voice in Christian literature.

These reinterpretations highlight her agency in reconfiguring the spaces of power available to her. Rather than being silenced by displacement, Eudocia harnessed her education, piety, and prestige to forge a legacy independent of court intrigue. Seen in this light, her so-called exile was not a defeat but an opportunity, transforming marginalization into enduring cultural and spiritual influence.

less

Bibliography

Primary Sources:

Eudocia’s Works

- Homerocentones (ed. E. Heitsch, Leipzig, 1963)

- Martyrdom of St Cyprian (ed. A. Garzya, Naples, 1970)

- Paraphrase of the Octateuch, Paraphrase of Zechariah and Daniel, and On Cyprian the Martyr in Photius Bibliotheca 183, 184

- On the Baths at Hamat Gadar (Green and Tsafrir, 1982)

Contemporary Sources

- Leo, Letter 123

- Socrates, History of the Church 7.21

- Cyril of Alexandria, Oratio ad Pulcheriam et Eudociam augustas de fide CPG 5220; ACO1.1.5.

Later Ancient Sources

- John Malalas, Chronicle 353-8 (14.3-8)

- Chronicon Paschale s.a. 420-423, 444

- Theophanes, Chronicle AM 5911, 5940-2

- Georgius Cedrenus, Compendium Historiarum I 590

- Zonaras, Epitome of Histories 13.22-25.

- Evagrias, Ecclesiastical History 1.20-22

- Marcellinus Comes s.a. 422, 431

- Life of Melania the Younger 56-9

Examples of women branded as adulterous

- Cicero (Clodia) Pro Caelio 31

- Tacitus (Messalina) Annals 11.26

- Anon. (Susanna) Book of Daniel 13

- Origen (Mary) Against Celsus 1.28-32

Secondary Sources:

- Burman, J. 1994, ‘The Athenian Empress Eudocia’, in Castrén, P. (ed.), Post-Herulian Athens. Aspects of Life and Culture in Athens A.D. 267-529, Helsinki: Finnish Institute at Athens, 63-87.

- Cameron, Alan. 2015, ‘The Empress and the Poet’, in Wandering Poets and Other Essays on Late Greek Literature and Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 52-99.

- Green, J. and Tsafrir, Y. (1982), ‘Greek Inscriptions from Ḥammat Gader: A Poem by the Empress Eudocia and Two Building Inscriptions’, Israel Exploration Journal 32.2/3, 77-96.

- Holum, K. G. (1982), Theodosian Empresses: Women and Imperial Dominion in Late Antiquity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Skinner, M. B. (2005), Sexuality in Greek and Roman Culture. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Sowers, Brian P. 2020. In Her Own Words: The Life and Poetry of Aelia Eudocia. Hellenic Studies Series 80. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_SowersBP.In_Her_Own_Words.2021.

- Usher, M. D. (1998), Homeric Stitchings: The Homeric Centos of the Empress Eudocia. Lanham, Boulder, New York and Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Issues with the Sources

Issues with the sources surrounding Eudocia’s life and works present significant challenges. While her Cento survives in full and her epigraphic poem on the Baths at Hamat Gader was found (nearly complete) in situ, her other writings are preserved only in fragments or summaries. Much of the biographical information comes from sources that are either unreliable or overtly hostile, requiring cautious interpretation.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully