A Monumental Lack of Representation

The Lincoln Memorial. Mount Rushmore. Marble renderings of George Washington just about everywhere. For many, these are the first to come to mind when considering honorary statues in public spaces—all men. The sculpted monuments that make up the United States’ landscape are predominantly male, despite women's vast accomplishments and contributions in American history. One may point to the Statue of Liberty in opposition to this, one of the most striking monuments in the country. However, Lady Liberty’s image, after a Roman Goddess, is one based upon a mythologized, symbolic ancient figure, not a woman who directly impacted the course of American History.

According to the Monument Lab, only 6% of the “Top 50” memorialized in monuments are women, a staggering number considering the influence of women in just about every sphere, despite the gender-based roadblocks they encountered. Frequently, statues of women are abstracted and feature fictional/mythological figures (such as Lady Liberty). As Gillian Brocknell reported for the Washington Post, there are more public statues of mermaids than congresswomen in America—an overall presence of female monuments far from the valiant, wisened depictions of men.

Just as the achievements of women have been overlooked and ignored in American history, so has their right to take up space in public spaces— their right to be honored as their male peers have.

Meet Patience Lovell Wright, Monumental Woman.

When reflecting upon crucial players in the American Revolution, history’s celebrated patriots are overwhelmingly male: Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, and Paul Revere, to name a few. One might envision quintessentially “masculine” images of the fight for liberty, of soldiers valiantly carrying American flags on battlefields, or Leutze’s mammoth painting of Washington confidently crossing the Delaware. But, women also played important roles within the Revolutionary landscape, dedicating their efforts to the patriot cause.

Art can inspire and mobilize its viewers, causing them to take action. As sculptor and revolutionary spy Patience Lovell Wright proved, however, action can also physically exist within art itself. A staunch American patriot and wax sculptor living in 1700s London, Wright used her status as the portraitist of Britain's elite to obtain information about the British military's movements, passing it to figures such as Benjamin Franklin.

Like many aspects of Wright’s life, her spying took an unconventional form. She allegedly hid messages inside her wax sculptures before they were shipped to America— chronicling tidbits she overheard among the British nobility. Along with this, Wright also subverted gender and class expectations of an American farmer’s daughter, living abroad and interacting with British high society.

An Early Innovator

Background Image Credit: Devry Becker Jones (CC0), November 14, 2020. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=152759

Born in 1725, Patience Lovell was a member of a Long Island Quaker family and later resided in Bordentown, New Jersey. Her family also followed Tryon beliefs, such as vegetarianism, defying mainstream culture at the time. Wright and her sisters wore veils from seven onward and only white garments. Even from a young age, Wright defied larger social expectations of how a girl/woman should present herself. She was educated in spheres such as agriculture and was taught to read and write. Such an intellectual advantage was not afforded to many women in 1700s America, providing Wright with the confidence and academic backbone to exist in spheres that historically frowned upon women.

The nine Lovell sisters experimented with artistic forms in childhood. Using resources around them, such as herbs, tree gum, and earth, they created paints to make pictures. Patience, always the trailblazer, began sculpting figures from dough and clay.

A Career Woman

Patience Lovell Wright married an older man, a Philadelphia farmer named Joseph Wright, in 1748. They had four children together, and when Wright was pregnant with her fourth, Joseph died, leaving Patience a widow with few resources to support her family. Joseph’s finances had been declining since the death of his father, leaving Wright in a difficult position. In the 1700s, perhaps other women would adopt the archetypal ‘helpless’ widow role. Wright defied gendered expectations, taking her childhood hobby of sculpting, which she also did in adulthood with dough to entertain her children, and turned it into a career.

Wright and her sister Rachel created commissioned work, mementos for grieving families of the deceased, and mythical/Biblical imagery. Such work defied Quaker notions regarding idolatry, but Wright created art nonetheless. Wright also made life-size wax figures, complete with hair and clothing. Due to the intrigue of these sculptures, Wright and her sister opened multiple waxwork studios in America. The sisters achieved great success: the studios offered a more affordable, accessible way for people to see wax art.

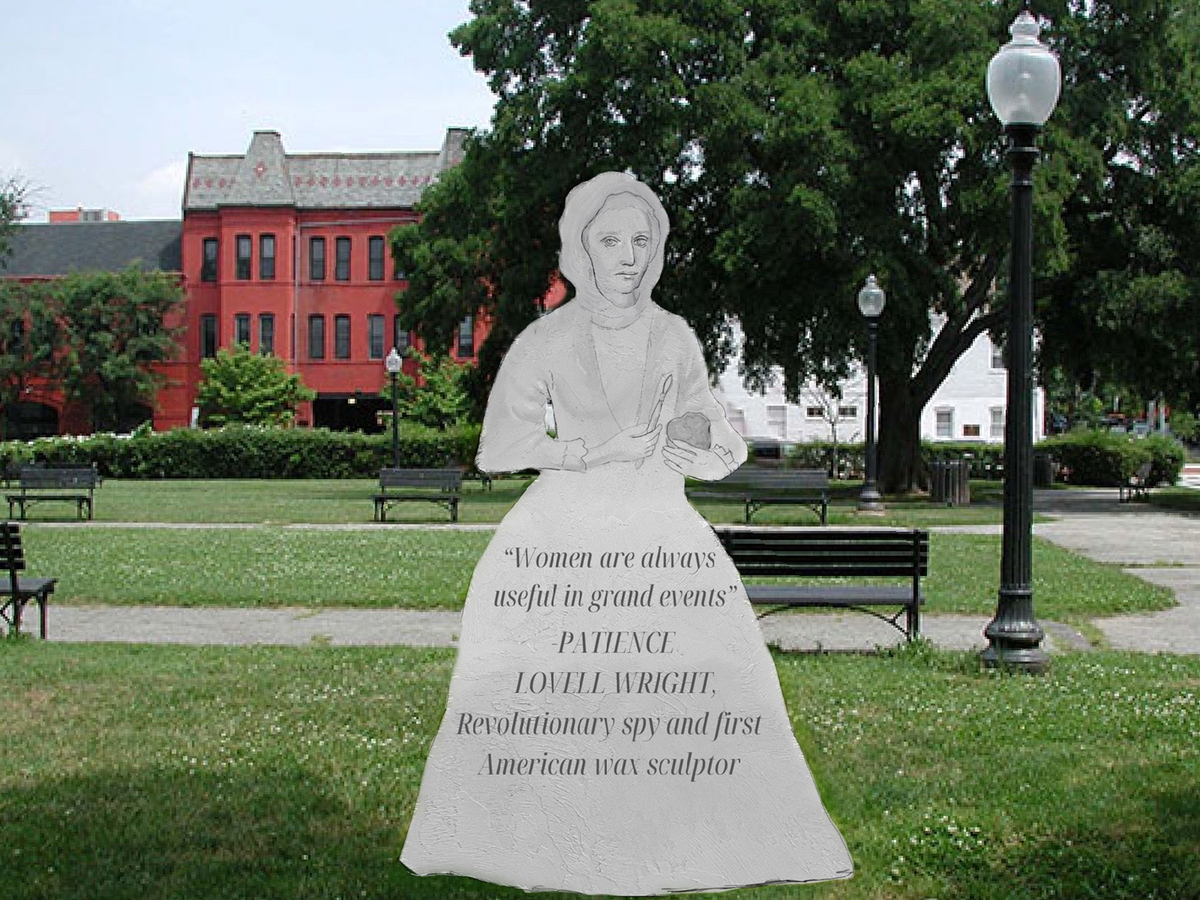

One of these waxwork studio locations was on Queen Street in New York City. Though Queen Street no longer exists, its location can be traced around the Wall Street/Pearl Street area on the south side of Hanover Square. The above image imagines a monument to Patience Wright in Hanover Square, depicting her profile similarly to her “Bustos” of sitters. The visual homage is adorned with a “Betsy Ross” version of the American flag, sculpting tools, and a recreation of Wright’s own signature. The piece loosely references a surviving John Dowman 1777 study of Wright, copyright The Trustees of The British Museum. Amid the contemporary hustle and bustle of city life, Wright’s monumental image would serve as a testament to the women who came before.

An Eccentric Performer

Background Image Credit: National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/articles/600076.htm

Wright’s successful waxworks studio was destroyed in a 1771 fire, and much of her work with it. Faced again with a tribulation, Wright persevered. With the assistance of friend Jane Mecom, Benjamin Franklin’s sister, Wright traveled to London and integrated herself within elite circles—both as a talented wax portraitist and an all-American novelty.

Her commissioned work soon turned into performance art. Wright would ramble and warm wax suggestively between her thighs. She would recall stories from American life with dramatic flair and kiss each American she encountered abroad. Patience would outright critique King George (whom she merely called “George”) on his handling of the American situation as she sculpted him, making her patriotism known. Eccentricity was innate in Wright’s persona. Some, like Abigail Adams, found it off-putting, while many found it entertaining. Wright’s list of connections during this time was extensive. King George III, Queen Charlotte, Benjamin Franklin, John Dickinson, members of Parliament, and Lords, among other prominent Americans and Brits, made up Wright’s significant network.

The sculpture rendering above depicts Patience Lovell Wright amid one of her eccentric sculpting performances, a heap of wax and sculpting tool in hand. “Carved” into her skirt, inspired by the role skirts would play in her performance, is a quote found through Charles Coleman-Sellers' research. The sculpture’s proposed location is Folger Park in Washington, D.C., a city with numerous monuments to male revolutionary figures (a handful of whom Wright herself corresponded with) but not as many of women.

A Revolutionary Spy

Wright did more than vocalize her patriotic opinions when abroad. She is also believed to have taken action, smuggling information overheard from her time amid British aristocracy. Further, not only did she spy, she did so by hiding knowledge within her sculptures, sending them ‘across the pond’ to people such as (allegedly) Benjamin Franklin or the Continental Congress. Some have theorized that Wright’s first information-smuggling was through the Earl of Chatham’s wax head, with sister Rachel Wells on the receiving end, passing the information to the Continental Congress (Coleman Sellers 69). In a surviving letter to a New York Reverend, Wright bluntly describes her disapproval of the British government: “All [the Parliament’s] schemes is to Inslave you all. Don’t be decevd. No honesty nor Honor is Expected from ths side of the watter — Stuped Ignorance is taken place, the Poor opresd, the Rich Proud and Impedent and [no] fear of god or men.” (Coleman Sellers 71).

As the severity of the Revolutionary War increased, however, Wright was effectively shunned by British high society due to her consistently outspoken patriotism.

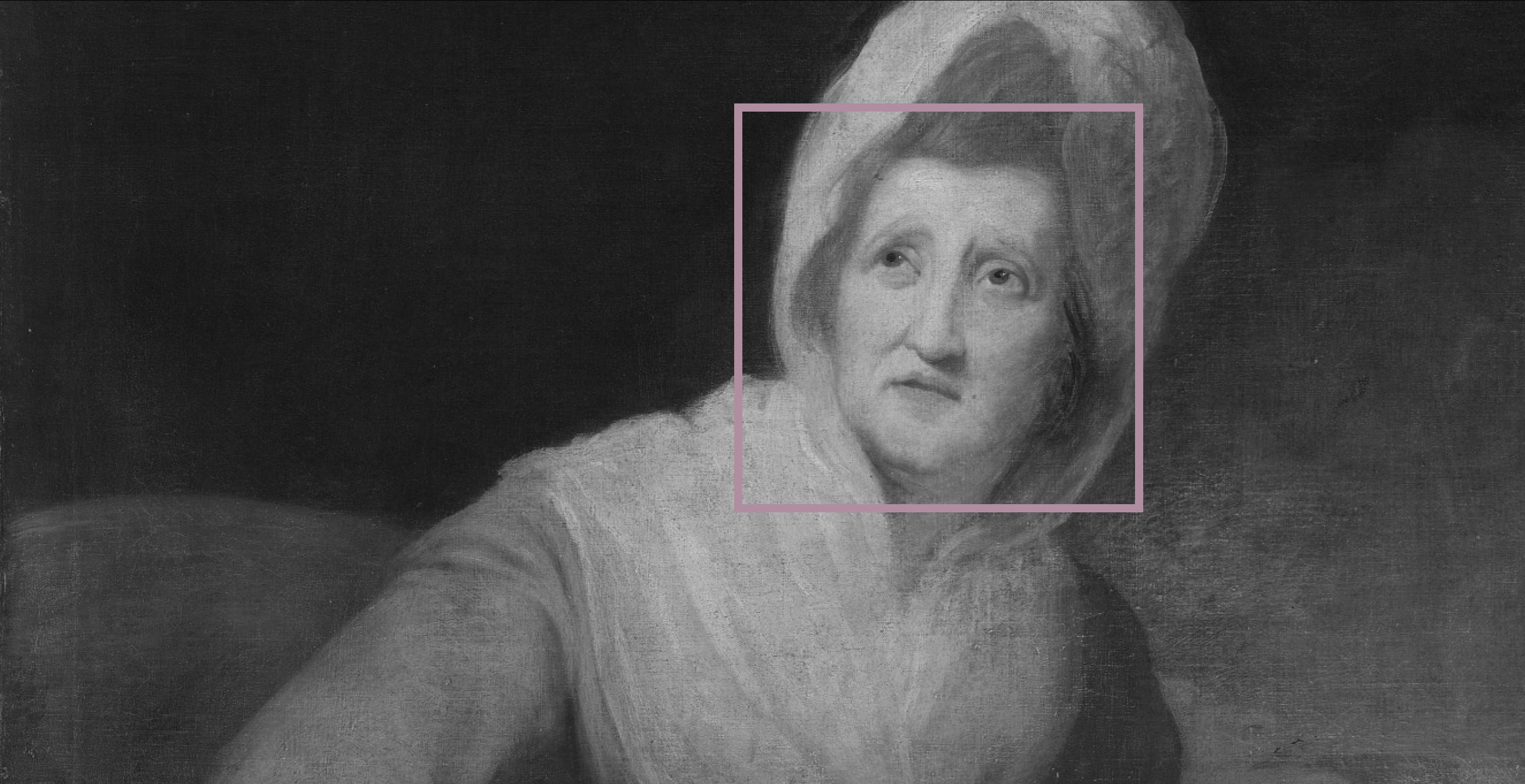

The above rendering visualizes Wright holding a bust of Benjamin Franklin and a scroll as a symbol for her information-smuggling. Her visage is loosely inspired by a portrait of young Patience Wright, housed by the National Portrait Gallery, and Wright’s ca. 1775 profile Bust of Benjamin Franklin, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Jefferson Square in Philadelphia, PA, serves as the backdrop, the location of one of her studios, and the receiving end of her spy information (i.e. Benjamin Franklin).

"I have travild through all the difirent ways of providence to Bring about the grand and most Extrordary Revolutions by the most unlikly means [sic]."

-Patience Wright, in a letter to Franklin, via Kokai’s article.

I. Overview

Patience Lovell Wright is considered the first American-born sculptor. She is also believed to have been a spy during the Revolutionary War, smuggling information from London to America inside her sculptures while serving as a wax portraitist to the British elite. An outspoken patriot and eccentric figure, Wright played a fascinating and underappreciated role in colonial American history.

less

II. Personal Information

Name(s): Patience Wright (née Lovell)

Date and place of birth: 1725, Long Island, NY

Date and place of death: March 23, 1786, London, England

Family

Mother: Patience Lovell

Father: John Lovell

Marriage and Family Life

Wright had nine sisters and one brother, one being fellow sculptor Rachel Lovell Wells (1735–1796), who married James Wells (Philadelphia shipwright) in 1750. Other known siblings included Rezine Anderson, Sarah Harker, Anne Farnsworth (also widowed young), and John Lovell Junior. Patience married Joseph Wright on March 20th, 1748, an older Quaker man, Philadelphia resident, and farmer. She was widowed in 1769 while pregnant with her youngest child, Sarah. Together, they had four children: Elizabeth “Betsy” Wright (1749–1792); Joseph Wright Jr. (July 16, 1756–1793), Phoebe Wright (August 22, 1761–1827), and Sarah Wright (b. 1770). Wright taught her son Joseph Jr. the art of sculpture. Wright’s son shared this knowledge with William Rush, who eventually founded the first art school/museum in the United States, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

Education (short version): Self-taught artist, able to read and write.

Education (longer version): Wright was taught to read and write. In her own account, according to biographer Charles Coleman Sellers, she and her sisters were taught “the Arts of Dairy, of Agriculture, and every branch of such useful and Pastoral knowledge.” Patience Wright did not receive a formal artistic education, a fact which critics and historians have argued hindered her full potential. A London Magazine notice referenced in an 1800s piece on Wright stated: “Her natural abilities are surpassing, and had a liberal and extensive education been added to her innate qualities, she would have been a prodigy.” Wright was self-taught, and her love for sculpting stemmed from a childhood hobby of making figures with wet flour and plants.

Religion: Growing up in a well-off Quaker family who also followed the teachings of trailblazing author Thomas Tryon, Wright was taught era-unusual contemporaneous values such as vegetarianism and wearing only white. She was also veiled in public from the age of seven onward. Later on, however, Wright began to defy values within the Quaker/Tryon ideologies through her art performances: contradicting the Tryon dictate against long, rambling speeches and the sexual conservatism in Quaker belief systems.

Transformation(s): One of the first turning points in Wright’s life was when she left home in New Jersey to marry an older man in Pennsylvania, despite strict Tryon beliefs.

The 1769 death of Wright’s husband marked a significant turning point in her life and endeavors. She was only in her 30s when she became a widow. With three children and one on the way, Wright faced financial difficulty, as Joseph’s finances had been declining since the death of his own father. Opposed to adhering to historical gendered assumptions of female widows as helpless, resigned, and dependent on other male-adjacent figures, Wright took matters into her own hands. She was encouraged by Francis Hopkin (neighbor and signer of the Declaration of Independence) to create sculptures for profit. She revived the childhood hobby, something she explored with her sister Rachel Wells in youth. Wright and Wells, in adulthood, began sculpting busts of Biblical figures from animal/tallow wax and commissioned portraits.

Another transformation occurred when her New York waxwork studio was destroyed in a fire on June 3, 1771. It was more financially successful than her Philadelphia location, and much of her work was lost along with it. She brought her talents to England, taking her family by ship on February 1, 1772, to a new life.

Wright was deeply passionate about America gaining freedom from British rule. In a 1774 letter written from London, Wright wrote: “All [the Parliament’s] schemes is to Inslave you all. Don’t be decevd. No honesty nor Honor is Expected from ths side of the watter — Stuped Ignorance is taken place, the Poor opresd, the Rich Proud and Impedent and [no] fear of god or men (sic).” Wright’s eventual, alleged, use of wax-sculptures to ‘smuggle’ messages to American patriots, working as both artist and spy, was sparked by the contemporary circumstances in Colonial America. Wright abandoned passivity on the situation when friction ensued, vocalizing her staunch support for the patriot side. The assumed stereotype of Americans as bold and uncivilized initially shielded her from backlash regarding her comments.

Contemporaneous Network(s): In London, Wright integrated herself in an elite social circle through the assistance of Benjamin Franklin’s sister, Jane Mecom, whom she was acquainted with in Boston by mere coincidence and took a liking to. She was good friends with Benjamin Franklin himself, who also gave Wright connections by recommending her to prominent clients through letters. Wright became acquainted with prominent, high-society figures of her time. She sculpted Parliament members, lords, and royalty—including King George III and Queen Charlotte, after which her popularity increased. While in London, she maintained contact with important historical figures such as Benjamin Franklin and John Dickinson, allegedly smuggling information about the British Military inside wax sculptures, which she obtained by integrating into elite social circles. After war erupted, however, Wright was pushed away by British nobility, refusing to conceal her staunch loyalty to the patriot movement. After her suggestion for rebellion on British turf, Benjamin Franklin also distanced himself from Wright. After being isolated from the aforementioned networks and finding an unsuccessful career in Paris, she returned to London. After the Revolutionary War, Patience was in contact with George Washington, thanking him for commissioning her son to create a wax bust. At one point in a surviving letter, Wright touches upon her desire to create more waxworks: “it has been for some time the Wish and desire of my heart to moddel a Likeness of generel Washington, then I shall think my Self ariv’d at the End of all my Earthly honours and Return in Peace to Enjoy my Native Country.” Washington responded: “If the Bust which your Son has modelled of me should reach your hands, and afford your celebrated Genii any employment that can amuse Mrs Wright, it must be an honor done me.”

less

III. Intellectual, Political, Social, and Cultural Significance

Works/Agency: In earlier stages of experimentation with waxwork, Wright and her sister sculpted mythological creatures and busts from the shoulders up. Her work was frequently created with animal fats such as tallow, though she used materials like bread dough to sculpt for her children’s entertainment. Wright first began creating works for profit by leveraging her role as a woman in Colonial America, and thus the more “sympathetic” gender, by creating commissioned portraits of families of their deceased children as mementos. Along with her sister Rachel, Wright created a prosperous wax-portrait business and eventually opened a New York wax museum in 1770, funded by financial assistance from lawyer Francis Hopkinson. Many of the exhibited portraits were of well-known figures, displayed in authentic clothing. Wright’s lifesize wax sculptures gained traction in America, with people captivated by her dressed figures, held up by metal frames. Oftentimes, these figures were staged in person-appropriate scenes, years before Madame Tussaud opened her wax museum. When a fire ravaged much of her impressive waxwork, she made her way to London, where she created a successful reputation as an artist, being commissioned by figures such as King George III, Queen Charlotte, John Wilkes and William Pitt, also becoming known for her sculpture performances.

Examples of Surviving Works:

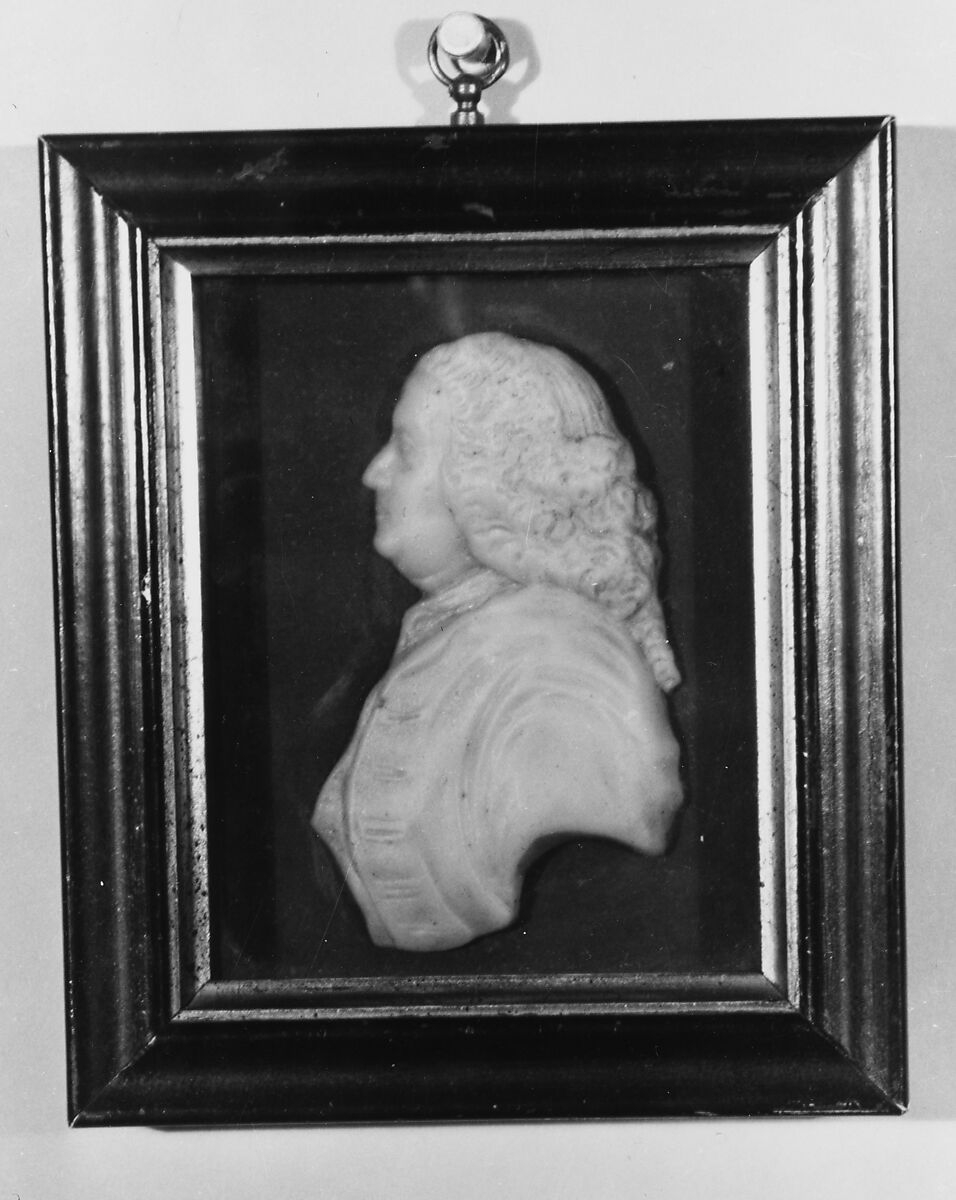

- Patience Wright, Profile Bust of Benjamin Franklin, 1775. Wax, glass, wood, and paper. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Patience Wright, Admiral Richard Howe, 1770. Wax and wood. Newark Museum of Art.

- Patience Wright, Wax Model Portrait of William Pitt, Earl of Chatham, 1779. Wax, glass, fabric. Westminster Abbey.

Contemporaneous Identifications: Patience Wright is typically acknowledged through the lens of the American Revolutionary War and art within colonial America.

Reputation: During her life, Wright established herself as both a successful artist and an enthusiastic performer. While focused on appealing to the upper class in America, she adopted a generic persona of an 18th-century mother after relocating to London. However, her departure from traditional expectations of a widowed woman in 1700s society led to a contentious reputation. Wright, in her performances, would, as observer Elkanah Watson stated via Kokai’s article, “[pour] forth an uninterrupted torrent of wild thought, and anecdotes and reminiscences of men and events.” Other elements contributed to her eccentric persona, such as her vegetarianism and kissing of people regardless of their gender. Further, she defied notions of modesty: putting slabs of clay up her dress, using her thighs to warm them. The added sexual suggestiveness of her performance diverged from her status as a modest farmer’s widow.

Despite being abroad when the Revolutionary War began and even knowing King George III (whom she referred to merely as “George”), Wright was undeniably a staunch patriot, staying in contact with Benjamin Franklin. Wright housed American prisoners of war in her London dwelling and even cautioned “George” against his behavior towards America. She is rumored to have worked as a spy for Franklin, gaining insight into British military information through her connections with London society. It has also been theorized that Wright was in contact with the Continental Congress, smuggling information inside of her wax figures. Some have speculated, such as biographer Charles Coleman Sellers, that Wright’s first information transmission was through the Earl of Chatham’s wax head, with sister Rachel Wells on the receiving end, passing the information to the Continental Congress. Ultimately, Wright’s pro-American attitude led to the demise of her reputation in London, and she moved to Paris in a failed attempt to revive her career, then eventually returned to England.

Legacy and Influence: Despite being well known among upper-crust circles during her life, Patience Wright is relatively unknown in contemporary popular culture. However, her legacy has prevailed. A children’s book about her in 2007. She is also the namesake of a Daughters of The American Revolution chapter in California. She has also been documented in Revolutionary War academia, though not as thoroughly as male figures from the period. Her home in Bordentown, New Jersey, has a plaque acknowledging her role as “First American modeler in wax and female spy.” However, the plaque’s content does not solely celebrate her accomplishments, instead adding her role as mother to Joseph Wright, “Designer of original U.S. coins.” Wright is also featured on the New Jersey Women’s Heritage Trail, with a marker describing her life's hallmarks. Unfortunately, Wright’s burial site in London remains unknown.

less

IV. Controversies

Controversy: Wright’s sexually suggestive sculpting performances challenged preconceived notions of gender in 1700s society, and hence sparked controversy. Such behavior contradicted surface-level notions of Wright as a humble Quaker widow and mother. Modern scholarship also points out Wright’s defiance of Quaker/Tyron rules, for instance, using animal fat to create sculptures despite a belief in vegetarianism. Wright's authenticity and self-contradictions ultimately added to her novelty in London. However, not all were entertained: Wright’s tone of voice during performances appeared unhinged, turbulent, something that observers like Abigail Adams found unpleasant, remarking: “her tongue runs like Unity Bedlam's.” . Adams also referred to Wright as the “Queen of Sluts” and “overfamiliar.” Contrary to the rigid class system of 1700s England, Wright did not change her behavior based on class and treated members of high society informally (i.e., referring to King George as “George” and unabashedly critiquing his decisions towards America). Wright’s unusual practice of kissing both men and women also caused discussion, specifically her desire to kiss every American she encountered in England. Such an outward display of patriotism would spark intense controversy in Wright’s lifetime. As an outspoken American patriot in England, this tension culminated when the Revolutionary War commenced. While her reputation as an eccentric American let her get away with outward critiques of British rule previously, her continued and unrelenting disdain for the Loyalist group led to her exclusion from London society as war began. After 1776, Wright’s name stopped appearing in British newspapers, and she was effectively shunned due to her political beliefs. Further, Wright was also eventually cut off from some American connections, such as Benjamin Franklin, due to her urgent desire to start another revolution in Britain to help the “poor and oppressed.”

New and Unfolding Information and/or Interpretations: Much of Wright’s work has been destroyed due to wax’s delicate nature and moldability. However, her work has circulated in online auction houses recently (i.e. a wax portrait of Washington in 2017), providing a more expansive look into the breadth of Wright’s sculpture. Much of the unfolding interpretations of Wright, such as her defiance of gender roles, have been built on already-known sources and accounts, including her letters and the written accounts of witnesses.

less

V. Clusters & Search Terms

Current Identification(s): wax sculpture, espionage, performance art

Clusters: woman artists, American revolutionaries, sculpture artists (ex. Madame Tussaud)

Search Terms: Patience Lovell Wright: American spy, artist, Quaker, 1700s, American Revolution, George III, George Washington, Colonial America

less

VI. Bibliography

Sources

Primary (selected):

Sellers, Charles Coleman. Patience Wright: American Artist and Spy in George III’s London. Wesleyan University Press, 1976.

Hart, C. H. "Patience Wright, Modeller in Wax." Connoisseur (Archive: 1901-1992), September 1907: 18-22. ProQuest.

Washington, George. “Letter.” Founders Online, National Archives. 13 January 1785. Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Confederation Series, vol. 2, 18 July 1784 – 18 May 1785, edited by W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1992, pp. 299–300. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-02-02-0218.

Waska, Frank E. “Mrs. Patience Lovell Wright. A Famous Modeler in Wax.” JSTOR. Brush and Pencil 2, no. 6 (1898): 249–52. https://doi.org/10.2307/25505303.

Wright, Patience Lovell. "Letter.” Founders Online, National Archives. 8 December 1783. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-12156.

Archival Resources (selected):

Brady, J. D. “REDISCOVERY OF JOSEPH WRIGHT’S MEDAL OF GEORGE WASHINGTON.” Museum Notes (American Numismatic Society) 22 (1977): 241–65. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43573555.

Felder, Deborah. "Patience Lovell Wright (1725–1786)." In The American Women's Almanac: 500 Years of Making History, Visible Ink Press, 2020. https://search.credoreference.com/books/Qm9va1R5cGU6MjI4Mw==

Kokai, Jennifer A. "Molding a Heroine: Patience Wright and Transatlantic Notions of American Female Patriotism." The Journal of American Drama and Theatre 21, no. 2 (Spring, 2009): 49-66,115, https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/molding-heroine-patience-wright-transatlantic/docview/197724776/se-2

Web Resources (selected):

Battlefields.org. "Patience L. Wright." https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/patience-l-wright.

Bordentown Historical Society. "Patience Lovell Wright (1725-1786)." https://bordentownhistory.org/patience-lovel-wright-1725-1786/.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. "Patience Wright." Encyclopedia Britannica, January 1, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Patience-Wright.

Marley, Anna O. "Patience Lovell Wright." AWARE Women artists / Femmes artistes, 2024. https://awarewomenartists.com/en/artiste/patience-lovell-wright/.

McCormick, David. "Sculptor Patience Wright Was the 'Madame Tussaud' of America." Antique Trader. https://www.antiquetrader.com/art/sculptor-patience-wright-was-the-madame-tussaud-of-america.

Serratone, Angela. "The Madame Tussaud of the American Colonies Was a Founding Fathers Stalker." Smithsonian.com, December 23, 2013. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-madame-tussaud-of-the-american-colonies-was-a-founding-fathers-stalker-180948610/.

less

Sculpting (W)right Sources

Brockell, Gillian. “America’s 50,000 Monuments: More Mermaids than Congresswomen, More Confederates than Abolitionists.” Washington Post, 2021.

Sellers, Charles Coleman. Patience Wright: American Artist and Spy in George III’s London. Wesleyan University Press, 1976.

Kokai, Jennifer A. "Molding a Heroine: Patience Wright and Transatlantic Notions of American Female Patriotism." The Journal of American Drama and Theatre 21, no. 2 (Spring, 2009):49-66,115. https://monumentlab.com/

Serratone, Angela. "The Madame Tussaud of the American Colonies Was a Founding Fathers Stalker." Smithsonian.com, December 23, 2013.

Images:

Dowman, John. Study for a portrait of Mrs Wright. 1777. Charcoal and black chalk, touched with red chalk, British Museum, © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Patience Lovell Wright by Robert Edge Pine, c. 1782. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Patience Lovell Wright (née Patience Lovell) published for London Magazine, line engraving, published 1 December 1775, National Portrait Gallery.

Profile Bust of Benjamin Franklin, Attributed to Patience Wright, ca. 1775, Wax, glass, wood, paper, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Young Patience Wright. National Portrait Gallery.

less

Bio

Lena Bramsen recently graduated from The New School with a degree in Creative Writing and was a member of the Writing and Democracy Honors Program. Her work frequently sheds light on the eccentric and dissident aspects of womanhood. She is presently part of The New Historia team, contributing to the feminist historical recovery of underrepresented women.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully