The New Historia asks, how does evidence and information about women’s experiences change our reactions and our actions?

How can the new knowledge allow us to make a difference in every woman’s life?

How do we change the laws of men to protect and champion the lives of all women?

Rape in Hittite Law

The Hittite Laws, a collection of 200 paragraphs of legal texts, were composed during the Old Kingdom (ca. 1650–1400 BCE) of the Hittite Empire, and remained in use by its ancient Indo-European people for some 500 years.

- Law 197: “If a man seizes a woman in the mountains [and rapes her], it is the man’s offense, but if he seizes her in her house, it is the woman’s offense: the woman shall die.”

- Law 64: “If the woman’s husband discovers them in the act, he may kill them without committing a crime.”

The Hittite Law text 197 dealt with the issue of female rape. It stipulated that if a woman was raped in the mountains, the fault was the attacker’s and he became an outlaw. However, if the rape occurred in the home of the victim, the fault was then laid upon her. This suggests that a woman was either never left in her home alone, or that submission in an attack was not tolerated, even if it was a matter of life or death. In the time period classified as the New Kingdom, women who chose to live a single life could be given a male slave through royal channels. A prayer recited by Queen Puduhepa to the goddess Lelwani when King Hattusili III was intensely ill discussed the allocation of a prisoner of war to the home of each single woman to assist her with heavier tasks.

less

Biblical Rape

Members of the priestly Hebrew tribe of Levi, the Levites were in power for more than 1,000 years. In an incident described in the Book of Judges, after a Levite’s concubine has been raped to death by Benjamite tribesmen, the Levite takes her body home and chops it into 12 pieces, which he sends as an announcement of the crime to the 12 tribes of Israel (Judges 19:21–29).

less

Heroic Rape

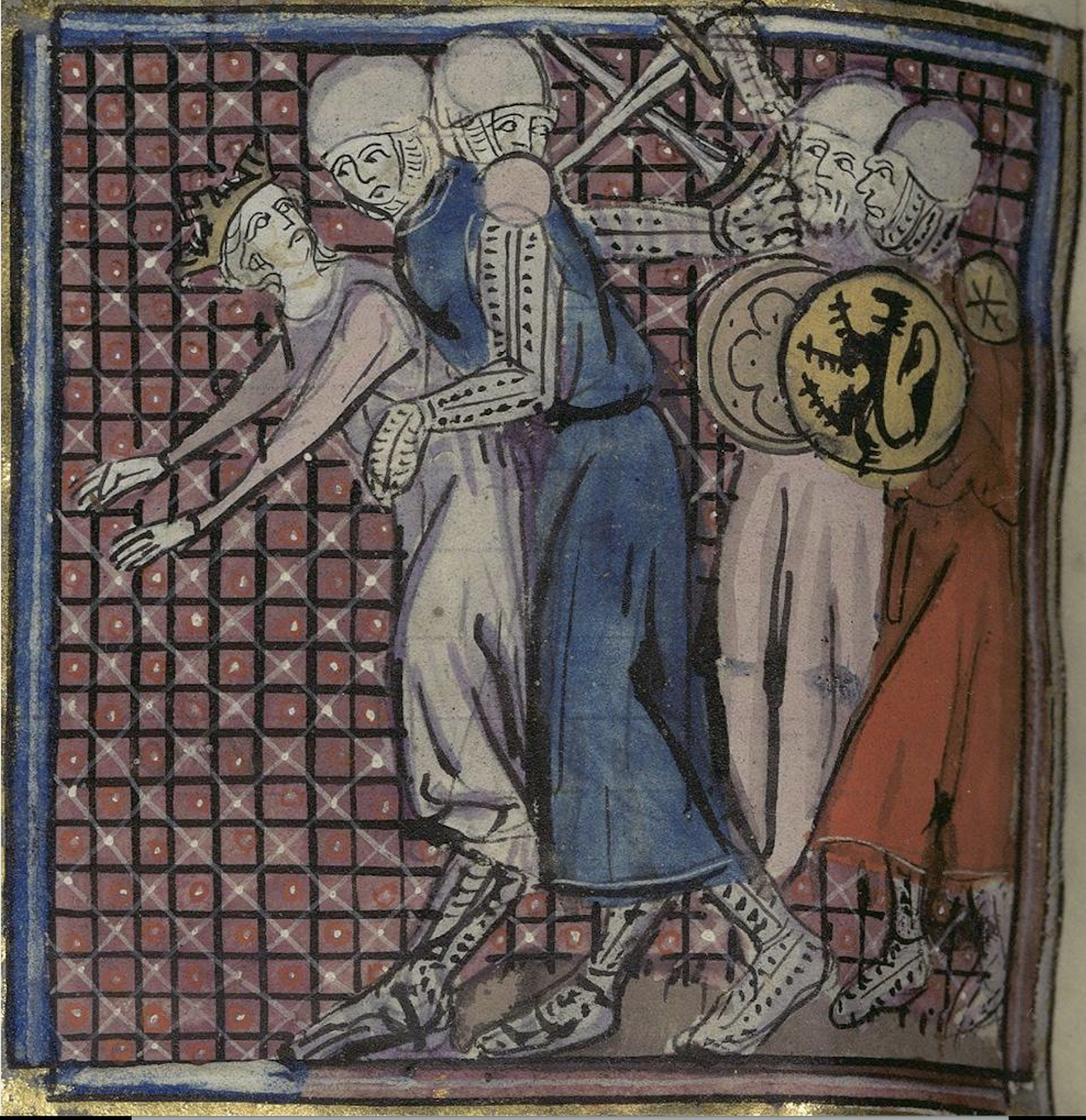

The cultural style of “heroic rape” was popular in the West from the 15th through the 17th centuries. Male artists depicted “heroic rape” to illustrate the importance of marital discipline, erotic stimulation, and the political power of great patrons.

less

The Romance of Rape

Ovid, Virgil, St. Augustine, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Percy Bysshe Shelley, William Butler Yeats—all wrote about rape, and great artists like Poussin and Titian painted and sculpted sexual violence. Their words and images formed an important part of classical education for boys and men. We still study and exalt these works as part of the foundations of human culture.

less

What of the women who lived the rapes?

Rape was a constant threat to all women, including widows like Christine de Pizan, nuns, and holy figures.

In her feminist history, The Book of the City of Ladies (1405), Christine de Pizan (1364–ca. 1430) describes rape as “douleur sur toutes autre”—“the greatest possible sorrow” for women. In her texts and the illustrations she chose to be illuminated in her printed works, Christine disrupts the traditional rape script, first by refusing to imagine women as victims of sexual violence and then by visualizing them as forceful avengers.

less

Classical Rape and Female Suicide

The tragedy of the legendary heroine Lucretia of ancient Rome was a popular trope about a pagan woman of virtue who committed suicide after being raped, in Lucretia’s case by the Roman Prince Tarquin.

According to Christine de Pizan in The Book of the City of Ladies, Lucretia’s final words were: “This is how I absolve myself of sin and show my innocence.... From now on no woman will ever live shamed and disgraced by Lucretia’s example.” (Pizan 162)

In a poem addressed to Lucretia, Juana Inez de la Cruz, the Spanish nun and philosopher (ca. 1648–1695), shares the view that Lucretia’s suicide was meant to preserve the honor and pride of the wronged woman by ending the many ills that plagued her. Yet Sor Juana questions Lucretia’s choice of death because suicide is considered a sin in the Catholic faith. The prize of honor is one which merits such sacrifice. Sor Juana celebrates Lucretia’s choice of taking her own life in order to protect her reputation, while maintaining that the choice itself by suicide is wrong and even dishonest.

Sor Juana writes, “¡Oh providencia de Deidad suprema! / ¡Tu honestidad motiva tu deshonra, / y tu deshonra te etemiza honrada!” (poem 154,1:282, 12–14)

“Oh providence of the supreme Deity! / Your honesty inspires your dishonor, / and your dishonor eternalizes your honesty!”

less

The War Against Women and Women at War

“Gentileschi’s painting can be read as a transposition of silence, threatening the man with the violence that is regularly enacted on women, showing what that violence looks like, making it visible by inverting the gender of its agents. In that shock, that disorder, that world upside-down, a woman’s voice is made.”

—Griselda Pollock, THE ART BULLETIN, SEPTEMBER 1990, VOLUME LXXII, NUMBER 3

“If women set themselves to transform History, it can safely be said that every aspect of history would be completely altered. Instead of being made by men, History’s task would be to make woman, to produce her. And it’s at this point that work by women themselves on women might be brought into play, which would benefit not only women, but all humanity.”

—Hélène Cixous, “Castration or Decapitation,” Signs, vol. vii, no. 1, Autumn 1981, 43

less

Is Consent Possible?

In the New World, rape was a tactic of the British and Hessian troops during the American Revolutionary War.

less

Canonical Contexts: Present and Future

Recent feminist scholarship considers Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet (1595) within the context of ancient and contemporaneous male writings about rape that draw upon, but omit, women’s actual accounts of abuse.

The tale of Harvey Weinstein and the #MeToo movement is part of this trajectory. So is the belief that women’s apparent silence signals consent. In fact, there is a lineage of women’s responses to the threats and realities of rape, and documents that reveal their unknown subversive strategies, which, at last, are being recovered.

Court cases, letters, and imaginative re-creations such as the art of Artemisia Gentileschi and others, through time and around the globe, now tell the real story.

Knowing this new history can make a difference in our time.

To this day, definitions for consent, legal and social, vary state by state and country to country. Understanding the complexities of consent is muddied by the long history of atrocities enacted upon women that were once legally acceptable.

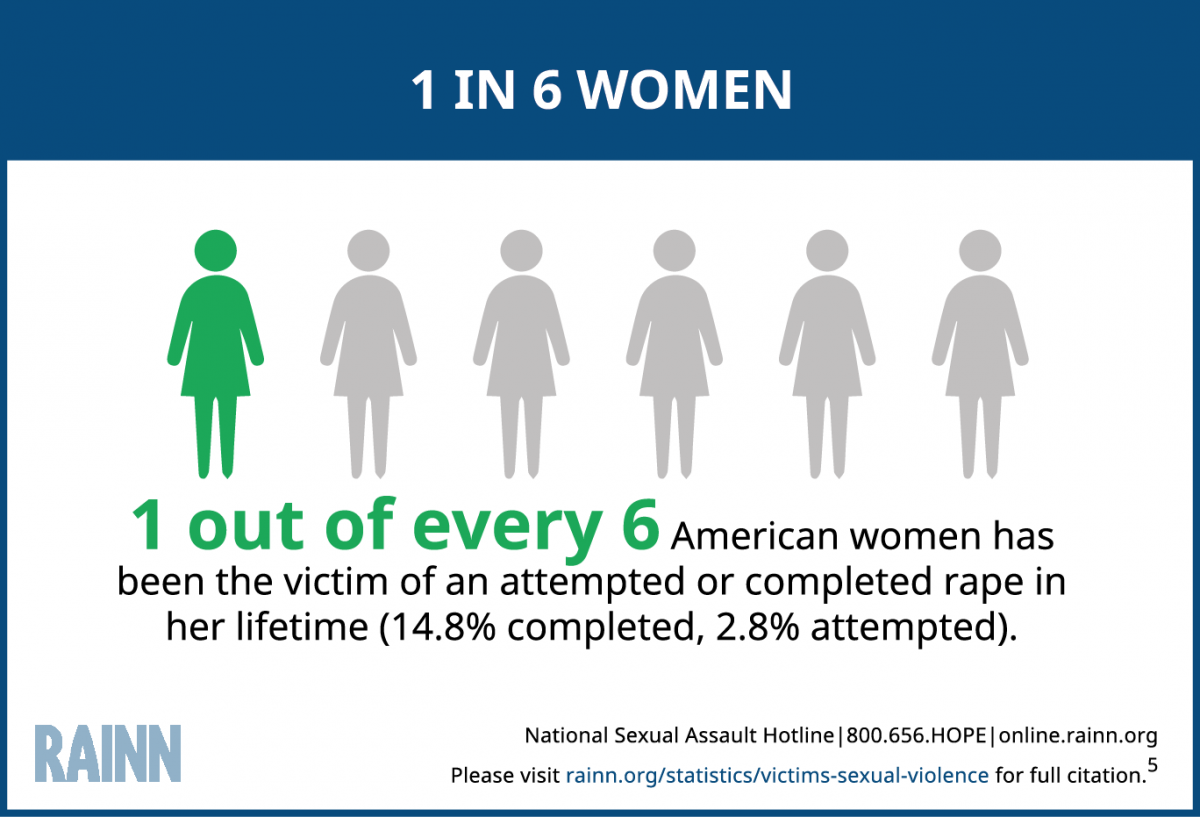

- See Rape statistics

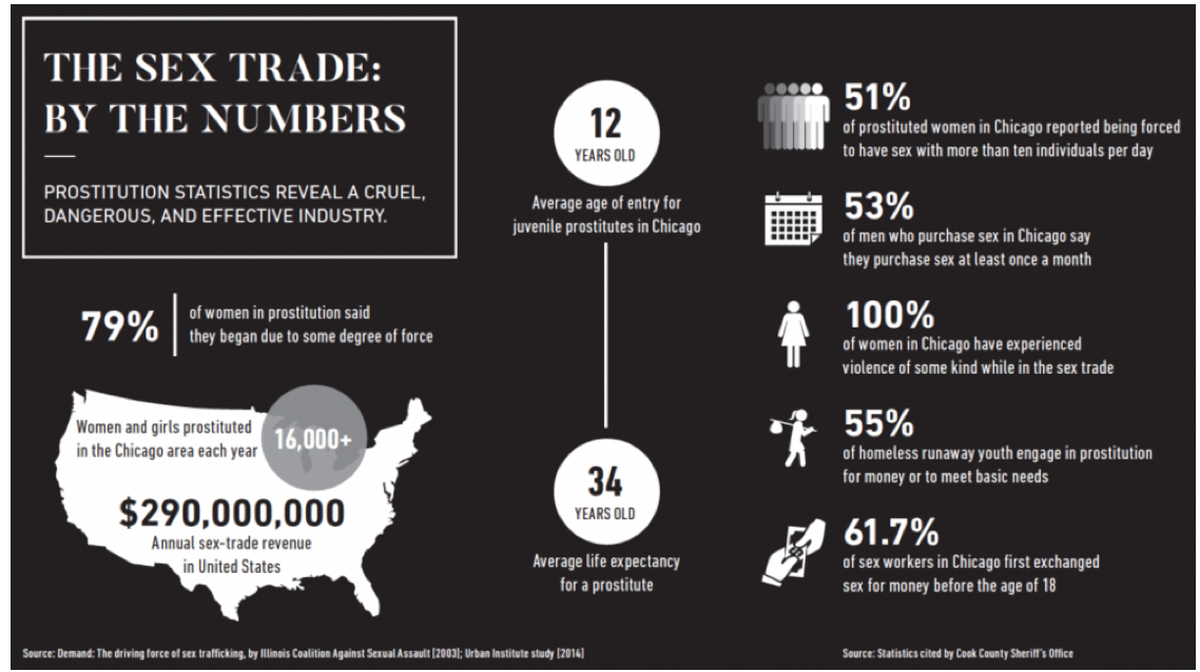

- See Sex trade statistics

Until 1975, sexual harassment was a nameless misery

The American educator Melvil Dewey (1851–1931), considered the father of modern libraries and who devised the Dewey Decimal System, was a serial sexual harasser.

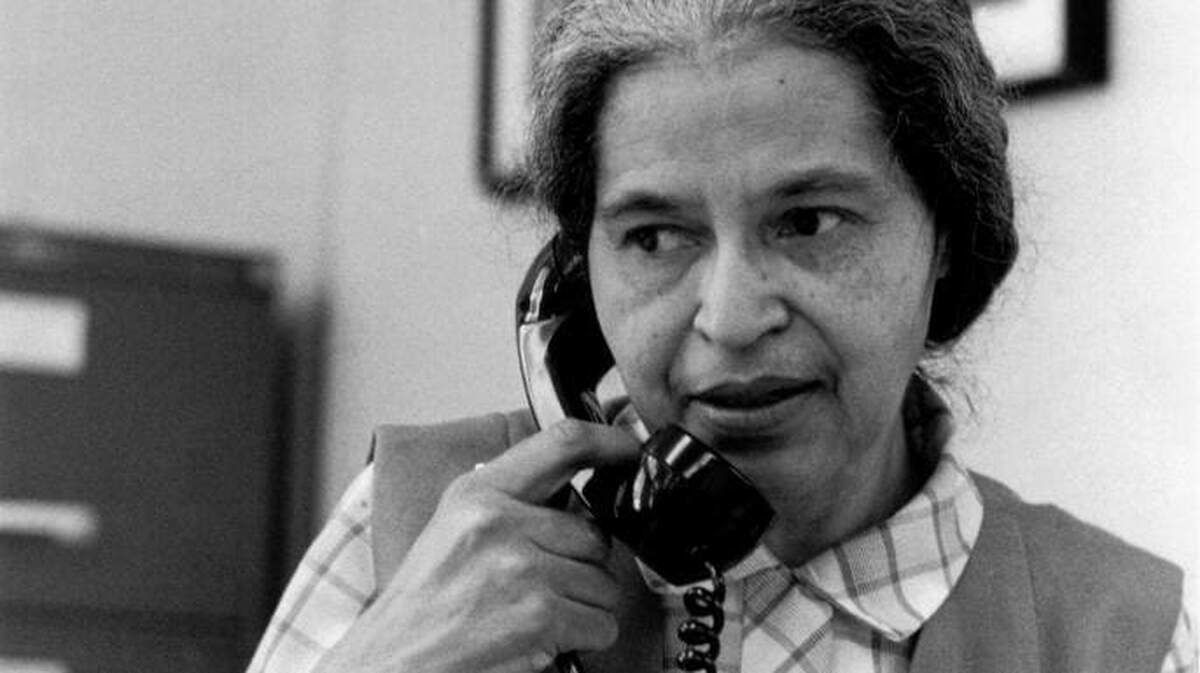

“People always say that I didn’t give up my seat because I was tired, but that isn’t true. I was not tired physically… No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.”

—Rosa Parks, Rosa Parks: My Story (1992)

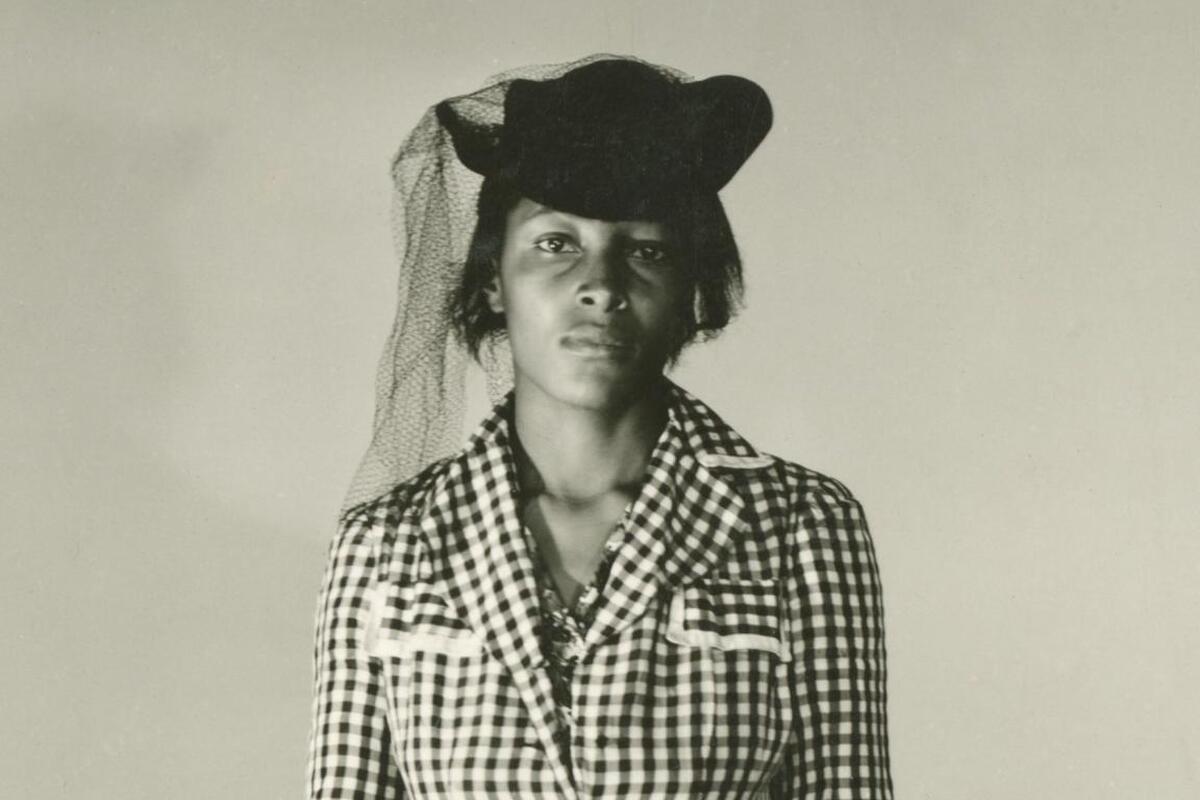

On December 1, 1955, the Black seamstress Rosa Parks (1913–2005) was arrested for failing to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama, city bus to a white man, breaking existing segregation laws. Largely unreported was that 12 years earlier she had been a sexual assault investigator. Throughout her career, she was determined that Black people, primarily women, who had been sexually assaulted by white men would get their day in court, as these crimes were often dismissed. She also worked to protect Black men from false accusations and lynchings. This work was personal to her because in 1931 a white male neighbor attempted to sexually assault her.

In 1944, Mrs. Parks was assigned the case of Recy Taylor (1919–2007), a woman who was determined to fight for justice in her own rape case and, in these ways, affected the course of civil rights. Tragically, Recy Taylor never saw justice: none of the six young men whom she identified were ever charged.

less

Laws

In the United States, it was not until 1993 that laws in all 50 states were changed to find marital rape a crime.

Today, only half the states have abolished all difference between marital rape and nonmarital rape.

The first known rape-related law emerged from Babylon ca. 1900 BCE, called the Code of Hammurabi. The law stated that any man who forced sex upon another man’s wife, or upon a virgin woman who was “living in her father’s house,” should be put to death. This was a property damage law.

Rape of a woman with no strong ties to a father or husband was of no concern.

English law in the 1600s created the first shift in society’s perception of rape by redefining the criminal act as “the carnal knowledge of any woman above the age of 10 years against her will.”

Common law in the U.S. declared that “a person commits rape when he has carnal knowledge of a female, not his wife, forcibly and against her will,” exposing the Babylonian underpinnings of legal interpretations and societal understandings of rape, reinforcing women as male property.

In 1954 the outcome of the Copeland v. State trial declared: It is rape only if penetration can be proved.

According to U.S. law, the court had to see that a woman had been violently forced with visible injuries, and convinced that she in no way desired sexual intercourse at the time.

Society and juries frequently dismissed women in rape trials as promiscuous and “asking for it.”

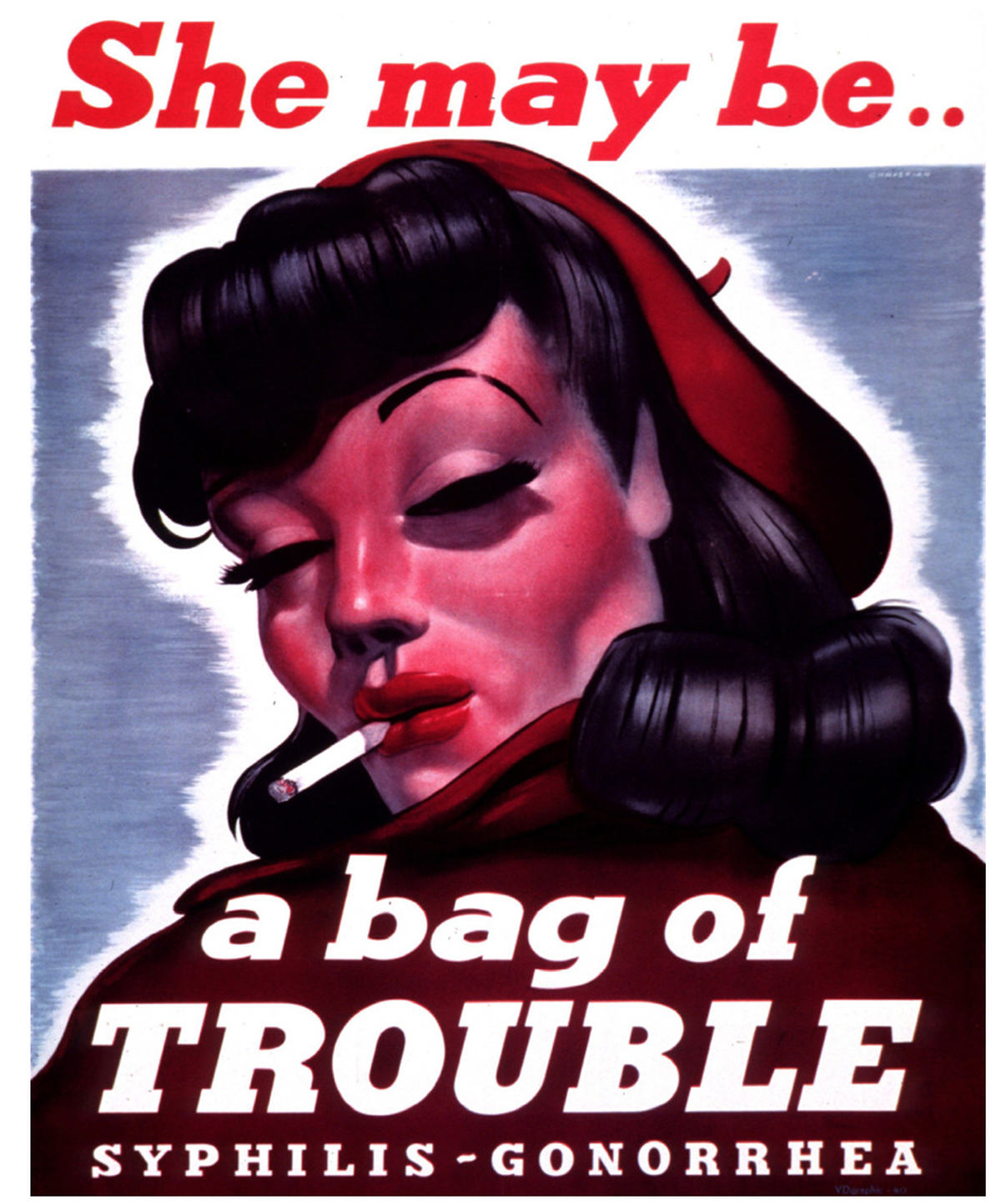

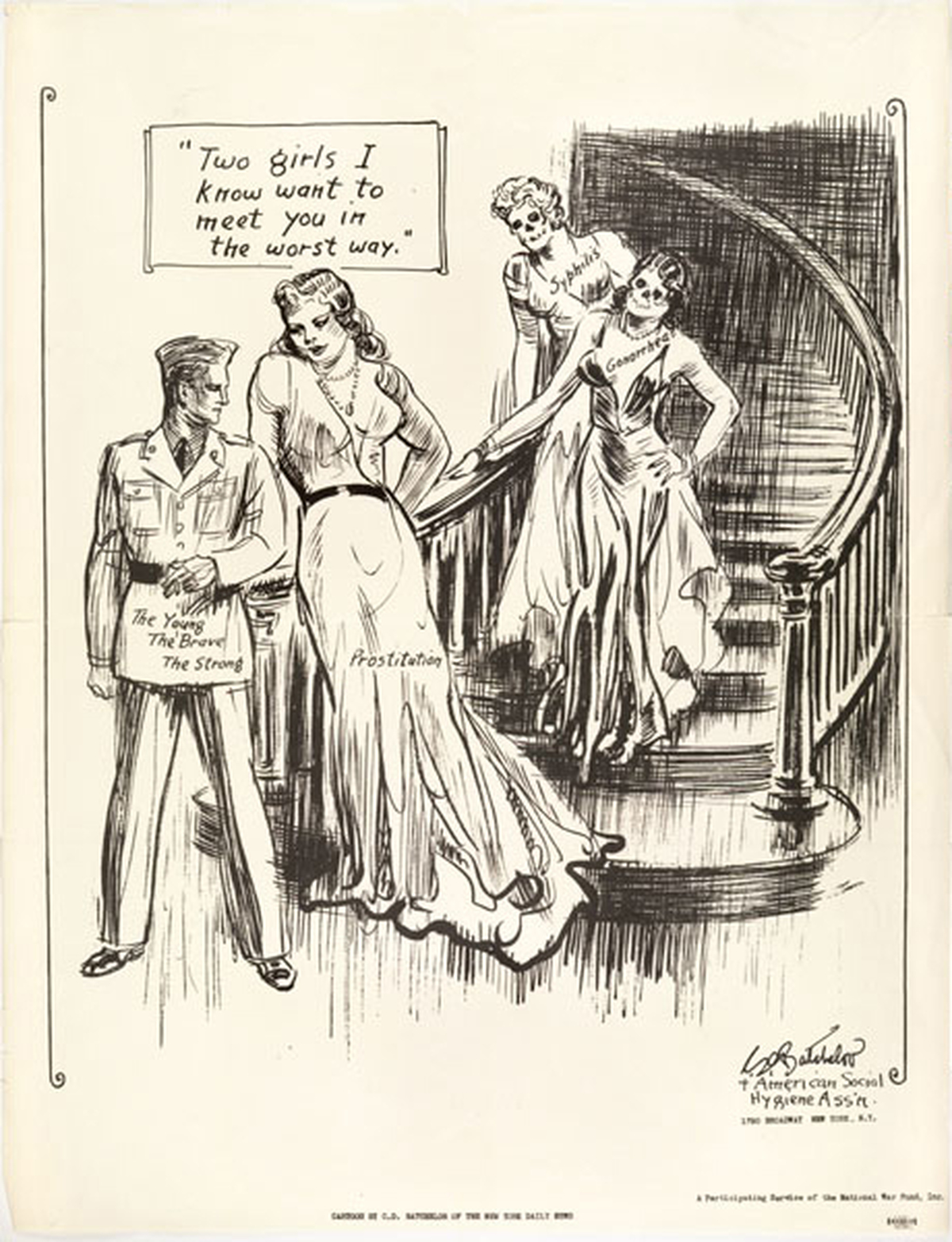

Under the Chamberlain-Kahn Act, which became federal law in 1918, women perceived as “sexually promiscuous” could be charged with a prosecutable crime. In the U.S., during most of the 20th century, an obscure program called the American Plan allowed for the mass imprisonment of women presumed to be “sexually immoral.” A woman might be detained for eating alone in a restaurant, walking to the drugstore, transferring to a new job, or for no reason at all. Suspects were imprisoned without trial and forced to submit to poisonous “treatments” based on the pretext that they had STDs. Propaganda posters such as the ones below were commonplace.

In 1919, nearly two dozen women were apprehended by authorities of Sacramento, California’s “morals squad” in a single day for no reason; this day was known as the Sacramento Sweep.

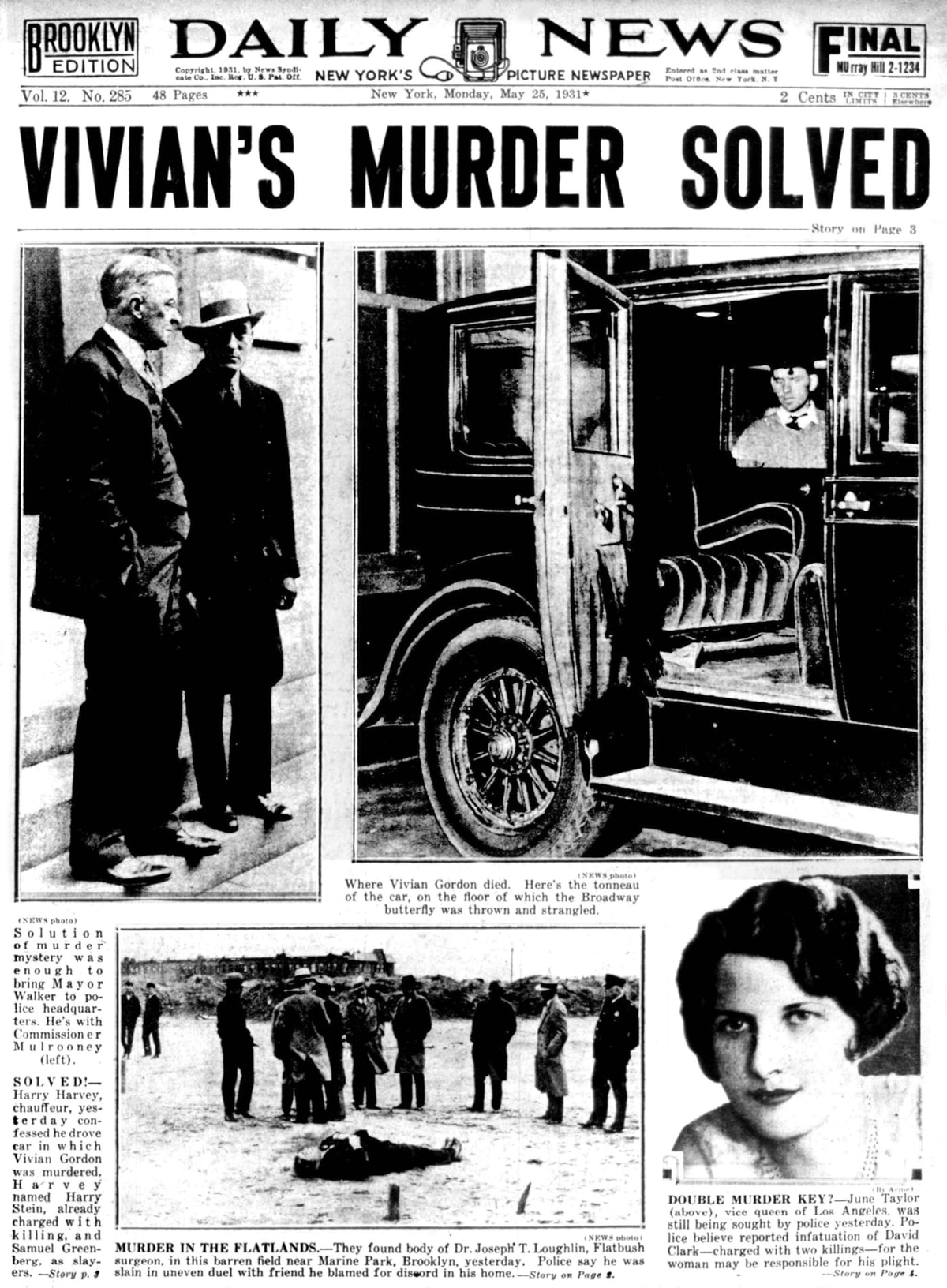

In New York City, in the early 1930s, when women were frequently charged with being sex workers, mob-affiliated police officers and judges stood to profit. Any mere whisper of a woman being perceived as promiscuous was so detrimental to her reputation that these “frame-ups” continued for years without question. In many instances, women were known to be arrested if they refused to have sex with the officer who apprehended them.

less

Rape as a Military Tactic

Women’s bodies have long been treated as terrains of war. According to recent reports released by Amnesty International, rape has become a deliberate, orchestrated military strategy.

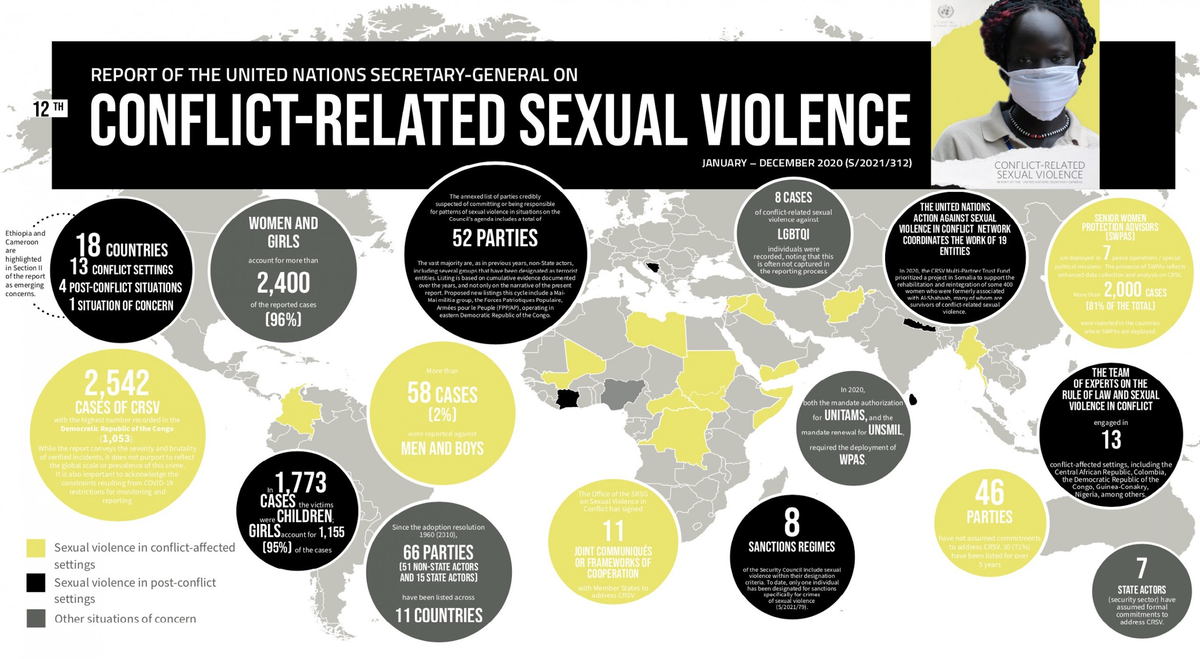

See conflict-related sexual violence statistics:

U.S. military men sexually assault one third of their fellow female soldiers.

LaVena Lynn Johnson was an E3 Private First Class in the United States Army. On July 19, 2005, while stationed in Iraq, she was discovered dead in her tent, and her death was ruled a suicide. Evidence of rape and battery led her family to believe that she had been assaulted and murdered by fellow soldiers, and that the Army covered it up to protect their reputations.

Vanessa Guillén was a soldier at Fort Hood, Texas, when she went missing on April 22, 2020. Her partial remains were discovered near the Leon River in Bell County, Texas. She had previously reported sexual harassment, and her murder sparked a wave of women in the U.S. military sharing their stories of sexual abuse, harassment, and assault.

From the official transcript of a 2008 hearing before the Subcommittee on Human Rights and the Law, of the U.S. Senate’s Committee on the Judiciary:

“It is not a crime under U.S. law for a non-U.S. national to perpetrate sexual violence in conflict against non-U.S. nationals, so the U.S. Government is unable to prosecute such perpetrators of wartime rape who end up in our country. There is also no U.S. law prohibiting crimes against humanity, one of the most serious human rights violations, which includes mass rape and other forms of sexual violence.” —Sen. Richard Durbin, chairman of the Subcommittee

less

The Rape of Nanjing

Beginning on December 13,1937, and continuing for six weeks, soldiers of the Japanese Imperial Army raped and murdered hundreds of thousands of unarmed Chinese citizens after capturing the city of Nanjing. Records of the campaign, also known as the Nanjing Massacre, were kept secret or destroyed. This egregious event still reverberates throughout relations between China and Japan.

A still from City of Life and Death, Lu Chuan’s 2010 fictional portrayal of the Nanjing Massacre.

From 1932 through 1948, women from China, Korea, and various other countries occupied by Japan were forced to be military sex slaves for the Japanese Imperial Army. Often under the age of 18, these women were referred to as “comfort women.”

less

Genocidal Rape

The UN has accused the Janjaweed militia in Sudan of using mass rape as a warfare tactic. The group’s actions have been described as “genocidal rape.”

Women of Darfur sacrificed their own bodily safety by collecting firewood, knowing that they were likely to be raped or assaulted, in lieu of the men of Darfur fetching the wood and being murdered. The women undertook this enormous act of courage and self-sacrifice in order to keep their communities and children alive and safe.

Women who survived the rapes were told by the perpetrators that they should feel “happy” and “lucky” to have the privilege of carrying a child of a different ethnic background. Or the assailant would tell the woman that she could return home and tell her husband that he “wasn’t man enough” to look after her.

In 1994, 100 days of mass rape and genocide took place in Rwanda; 800,000 Rwandans were murdered by ethnic Hutu extremists.

We must widen our understanding of rape during and outside of wartimes. NORCAP (Norwegian Capacity, provider of global expertise to the Norwegian Refugee Council) expert Katia Urteaga Villanueva, speaking of Ukraine as an example, has said, “We need to widen our understanding of sexual violence. Sexual violence is not happening only when someone points at you with a gun and then rapes you. If you have lost everything in an emergency and the only thing you have to negotiate with in order to survive is sex, then you may see no alternative but to swap sex for food, protection, and other survival needs.”

In August 2014, the Yazidi people of Sinjar in Northern Iraq were targeted by members of ISIS who sought to annihilate the community through murder, torture, and systematic, premeditated rape and kidnap in order to subject Yazidi women to sexual slavery. Many of the girls who were brutally attacked were as young as 12.

As the community in Northern Iraq pursues healing, instances of PTSD have been reported in up to 90% of the women, many of whom suffer illness, depression, anxiety, dissociation, and severe flashbacks.

One of the most extreme instances of conflict-related sexual violence occurred in Germany during World War II. Between the months of January and August in 1945, it is estimated that roughly two million German women were raped by Soviet Red Army soldiers, making this the largest incident of mass rape that we know of in history.

Rape as a tool of war and violence is born of and deeply rooted in misogyny. Boys are taught destructive lessons in masculinity tied to violence, and this harms men as well as women. Conflict-related acts of sexual violence are carried out against men, too. Sexual violence can be used as punishment for stepping out of line, or expressing views that fall outside of what it means to “be a man.”

Understanding this may help in efforts to liberate women from the confines of gender definitions associated with docility, objectification, and subjection to violence, and to unlearn lessons about masculinity that are taught to young boys and that harm them while also facilitating women’s oppression.

The reverberations of rape as a tool of war echo in the destruction of families and communities, and are felt throughout generations of subsequent trauma, long after the original conflict has ended.

less

Mental Health and Medical Abuse

In Ireland and the United Kingdom, from the mid-1700s until as late as 1996, pregnant women who were presumed to be “promiscuous” or otherwise “fallen” could be confined for life and made to work without pay in one of the Magdalene Laundries, a system of Roman Catholic asylums that also held orphans and abused children. Magdalene asylums were also established in Australia, Sweden, and the United States.

In 1993, a mass grave containing 155 corpses was uncovered on the former grounds of the Donnybrook laundry in a Magdalene convent in Dublin, which operated from 1837 to 1992. Over the decades, some 10,000 to 30,000 women (the number is debated by scholars) are estimated to have been kept there.

In 1855, J. Marion Sims founded the Women’s Hospital in New York, the first hospital devoted solely to women’s health, and is considered the “father of modern gynecology.” Many of Sims’s most notable medical discoveries were found to be the direct result of experimentation he performed on enslaved Black women and poor Irish women without their consent. He conducted the first artificial insemination on a woman who could not conceive due to her husband’s low sperm count. During what was meant to be an examination, in front of six medical students, without her knowledge or consent, he knocked his patient out with chloroform and inseminated her with the sperm of one of the medical students in the room who was thought to be the most conventionally “attractive.” Following the birth of the child, Sims informed the woman’s husband, and the two men decided that it would be in her “best interest” not to inform her.

In the 1970s, Susan Griffin wrote that rape was a “form of mass terrorism.”

Women are often imagined in parts; intersectional feminism attempts to understand the aspects of identity that frequently intersect at multiple systems of oppression, whether of race, sexuality, poverty, disability, religion, or otherwise. Transgender women, for example, face dual gender oppression in the form of misogyny and transphobia.

The singular access through which we typically view these women segments them into isolated parts of their experience. There are studies that may show violence against women, violence against transgender people, and violence against the Black community, but to make visible the experience of a Black trans woman, in familiar historical recovery fashion, we must gather the available glints of this data and imagine a cohesive picture.

Which is to say, navigating the brambles of these statistics and how they interact can be challenging.

RAINN (Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network) describes the complexities behind their data as such: “As a community, LGBTQ people face higher rates of poverty, stigma, and marginalization, which put us at greater risk for sexual assault. We also face higher rates of hate-motivated violence, which can often take the form of sexual assault. Moreover, the ways in which society both hypersexualizes LGBTQ people and stigmatizes our relationships can lead to intimate partner violence that stems from internalized homophobia and shame.”

Studies suggest that around half of transgender people and bisexual women will experience sexual violence at some point in their lifetime.

Transgender women face great risk of violence, oppression, and abuse in many forms.

According to RAINN, 21% of transgender, genderqueer, and nonconforming college students have been sexually assaulted, compared with 18% of non-TGQN females, and 4% of non-TGQN males.

Transgender women are still incarcerated with men, putting their lives in imminent danger, and often facilitating environments rampant with sexual abuse.

Fifty-nine percent of transgender inmates reported having been sexually assaulted within a California correctional facility, compared with just 4.4% of the incarcerated population as a whole.

A study from 2007 suggests that transgender prisoners are, on average, 13 times more likely to be sexually assaulted than cis-gendered male prisoners.

Jasmine Rose Jones is a woman who has spent much of the last 23 years incarcerated in a men’s prison, subjected to years of gender-based violence.

Dee Deidre Farmer, the first transgender plaintiff in a Supreme Court case, was convicted of credit card fraud in 1986 and imprisoned with the general male population at the Federal Correctional Institution, Oxford, in Wisconsin.

Although the Supreme Court denied Farmer’s request to adopt an objective test for “deliberate indifference,” the landmark decision in Farmer v. Brennan found that deliberately failing to protect incarcerated transgender people from violence or abuse of any variety behind bars qualifies as cruel and unusual punishment. Despite this, incarcerated transgender people, particularly women, are willfully endangered every day by way of these transphobic imprisonment practices.

Recently, global uprisings protesting sexually motivated femicide have brought this accumulating history of violence to the forefront.

In Canada, along a highway colloquially referred to as “The Highway of Tears,” dozens of indigenous women and girls have been murdered or have vanished without a trace. These crimes are often sexually motivated and carried out by workers moving through logging towns under the presumption that they will never be caught, and that no one will care to look for these women.

As of 2016, the most recent year for which figures are available, Canada’s National Crime Information Center has reported 5,712 cases of missing and murdered indigenous women. In the U.S., the National Missing and Unidentified Persons database reports only 116 cases, a number widely recognized as a gross undercount.

less

Bios

Lauren E. McCarthy is a senior undergraduate student at Eugene Lang College of The New School, where she is pursuing a dual BA in psychology and literary studies. Her research focuses on thought and language mapping, memory organization in early childhood trauma, and interdisciplinary applications of neuroscience, as well as dissociation and comorbidity in the clinical realm. She works within The New Historia as an information-alchemist, using cognitive-minded spectacles to galvanize the data of the archive within public spaces.

Gina Luria Walker is the director of The New Historia.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully