From the start of Professor Luria Walker’s Enlightened Exchanges course, I found myself inspired and overwhelmed. Entering this class having just discovered Mihri Hatun, I felt fortunate to be in this academic space. The class provided me with insight into how to approach Mihri’s life and the lives of other historic women. In producing my final, I focused primarily on the themes of performance and subversion in relation to the women we discussed in class. I found that Mihri was similar to Margaret Cavendish in some ways. Both women broke into overwhelmingly male-dominated spaces, using their words to enter and subvert them. I also found an interesting parallel in the use of satire and humor by both women. Neither of these women was convinced by the systems of the world and questioned sociocultural structures within their works.

I. Personal Information

Name(s): Most commonly known as Mihri Hatun (Lady Mihri). Her real name might have been Fahrünnisâ or Mihrünnisâ. Mihri is believed to be her pseudonym. Hatun was her title, which translates as “a woman whose importance is as great as a man's.”. She has also been nicknamed “Kelimelerin Sultani,” which translates to “the Sultan of words.”

Date and place of birth: Mihri Hatun was born in Anatolia in Amasya. Noevidence states her exact birthday. Mihri is mentioned taking part in Bayezid II’s Meclis, a gathering for social purposes or entertainment, where poetry was often performed. Bayezid II was the eighth Ottoman Sultan, ruling from 1481-1512. Hence, it is assumed that Mihri Hatun was born between 1456 and 1460. She is also believed to have grown up with another poet from Amasya, named Hâtemî (Müeyyedzâde Abdurrrahman), and there is evidence that he was born in 1456. The two poets wrote parallel poems to one another, and it is speculated that they were lovers.

Date and place of death: According to Amasya’s historical records, Mihri Hatun died there. However, the date of her death cannot be confirmed. Some sources claim she died in 1506. Others stateshe may have lived until 1512. Her grave was possibly placed in the tomb of her great-grandfather (Pîr Şücâaddin İlyas) located in the neighborhood of Savadiye. The occupants of the tomb are known to be Pîr Şücâaddin İlyas, his son-in-law (Pîr Celâlüddin Abdurrahman Çelebi), and his grandson (Pîr Hayrüddin Hızır Çelebi). There are four unmarked graves among them, perhaps their wives or daughters. It is believed that Mihri’s grave is amongst these four. There are no documents that can confirm which grave specifically belongs to Mihri.

Family: Mother unknown. Mihriwas a part of a respected, wealthy upper-class family. Her father, Yahyazade Mehmet Çelebi, was the kadi (judge) of Amasya. He was also a poet, writing under the pseudonym Belâyî.

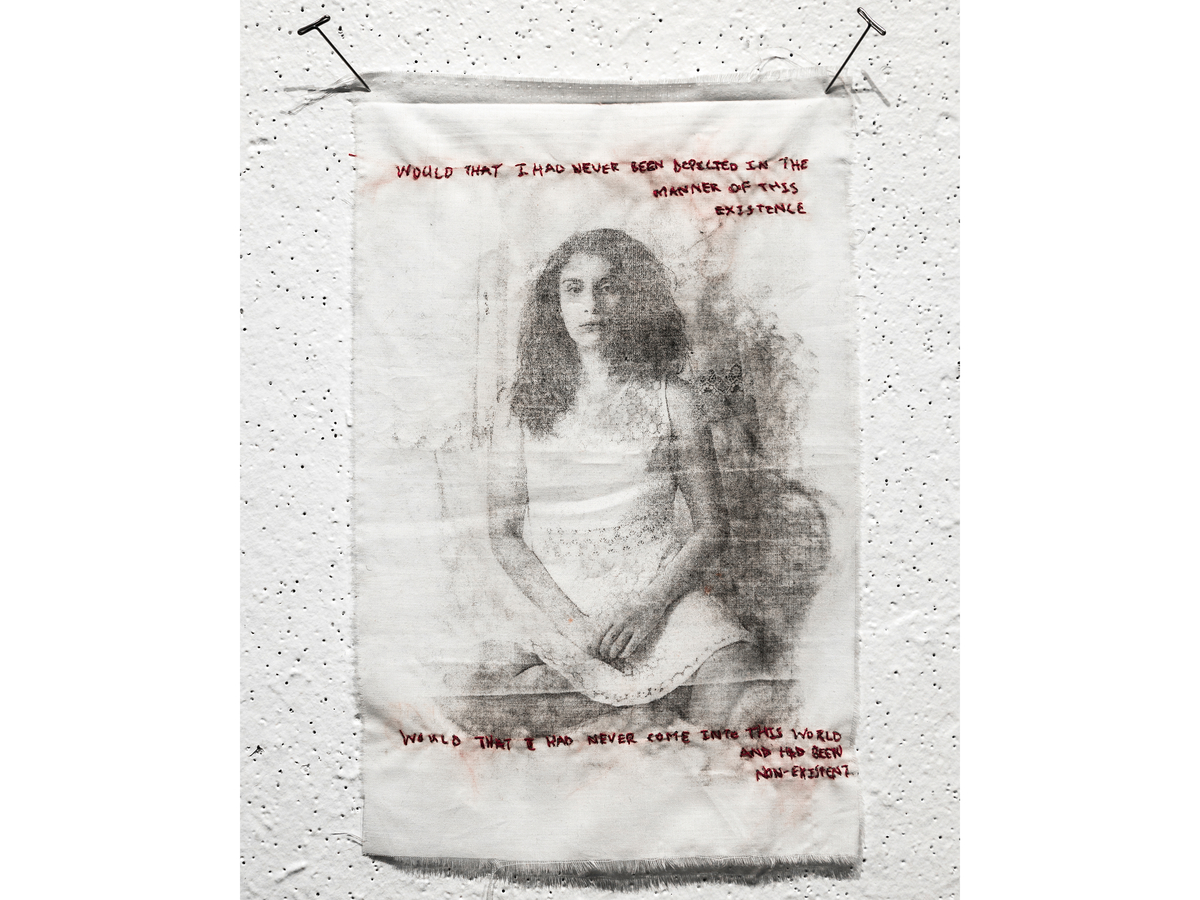

Marriage and family life: Mihri was never married and rejected marriage altogether. Although she writes about being in love with multiple men, she never married. She is imagined to be a virgin; which became a way to reiterate that her chastity made her closer to being a man, because she rejected motherhood.

Education: Her father encouraged her to write poetry and provided her with a private education in Science and Literature. She knew both Arabic and Persian and was known primarily for her expertise of Islamic law and women's issues.

Religion: In her poetry, she references specific gendered mythsestablished within Islam. It is unclear whether she practiced Islam, but she was well educated on the subject. She was interested in the story of Yusuf and Zuleyha. Zuleyha was the wife of Aziz and pursued the Prophet Joseph. Her actions are deemed “whore-ish” and “scandalous.”There are moments in Mihri’s poems where she relates her own actions to Zuleyha’s. Mihri shows a sophisticated comprehension of religion being used as an oppressive tool, subverting and questioning it. The following is an excerpt from a poem where she references Zuleyha.

“I’ve come, rubbing my face in the dirt, making my way right to you

Oh monarch, I wish I might reveal my sorry plight to you

Of all world’s kings, you are the king so famed for justice

That the sun comes to your door each day in service to you

O you rose-cheek, the nightingale of the soul recites

Praises day and night, at dawn and dusk to you

O my lord, the fire of jealousy has consumed this thirsty heart in flames.

Don’t leave me in the darkness of grief, let Hizr be a companion to you

O Mihri, let it make you as youthful as Zuleyha

Should the monarch turn his Joseph-like gaze to you”

less

II. Intellectual, Political, Social, and Cultural Significance

Reputation: Receipts indicate that she was compensated for her poetry in a study of Bayezid II’s gift registry, conducted by Hilal Kazan. She was paid a total of 10,500 Akce. Mihri was recognized for her poetry during her lifetime by famous male Ottoman poets, such as Necati and Makami, who wrote parallel poems to hers. She was known for her manliness and her virginity. She has been intentionally excluded from Turkish intellectual history. She is not mentioned outside of Amasya, her hometown, and there is likely no mention of her existence in Turkish education.

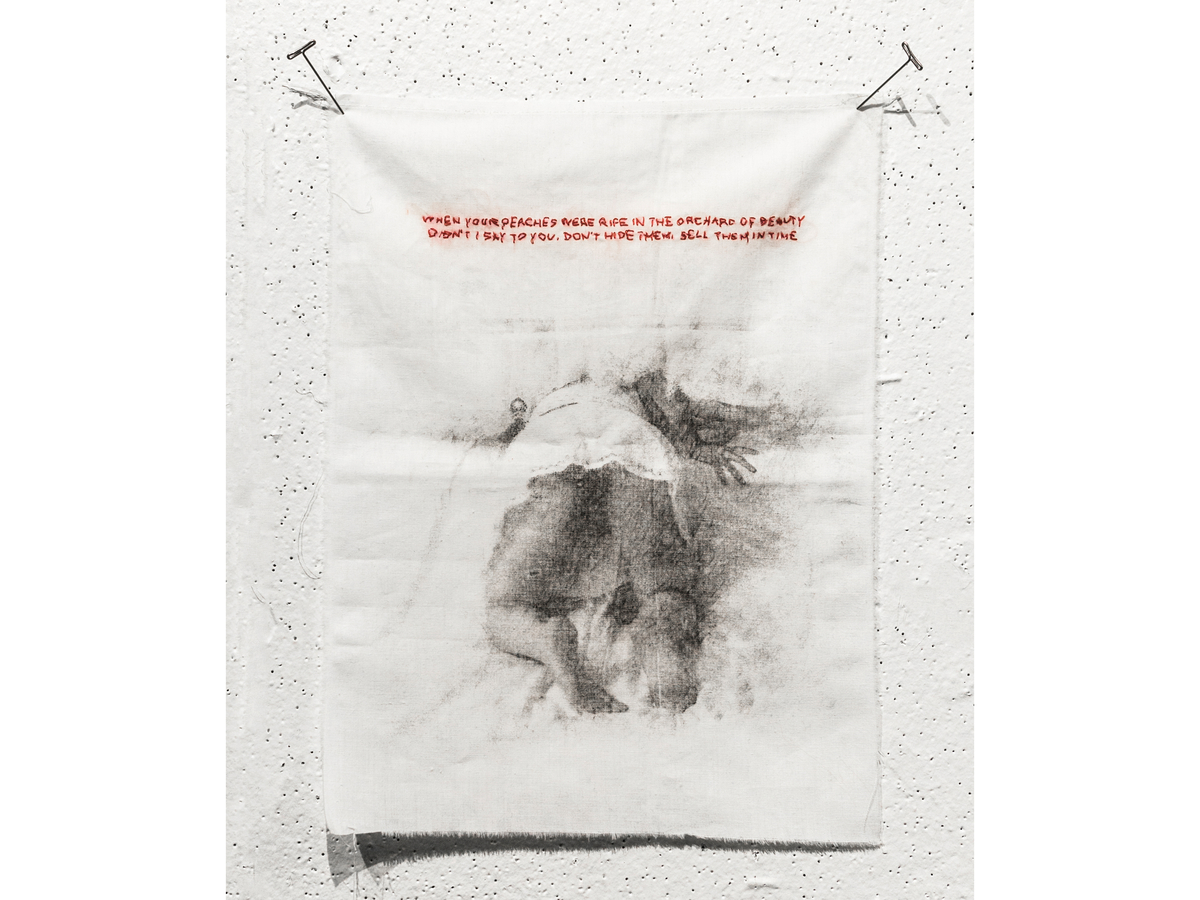

Transformation: Mihri transformed the battlefield of poetry by using her marginal position as a tool of subversion, claiming herself to be equal. She performs masculinity by showing courage and fearlessness. An excerpt from one of her poems states

“They say your rival boasts and says, “I’ll kill her one day”

If he’s a man, let him come and I’ll show manliness to that unmanly coward

What matter, if Mihri should risk her life on the battlefield of love for you

At times your glance was sword to her and your curl made a hoop”

Legacy and influence: In the poet’s hometown of Amasya, institutions and sites have been dedicated to Mihri in memoriam. A primary school in Suluova, a town in Amasya, is named after Mihri.

An annual poetry contest in Amasya, established in 2010, was also named in Mihri’s honor. The Mihri Hatn Culture House is also located in Amasya.

Contemporary identifications: 21st century studies on Mihri Hatun include:

- Türk Safosu Mihri Hatun by Sennur Sezer (2005)

- Kelimelerin Sultani Mihri Hatun (2015)

- Mihrî Hatun: Performance, Gender-Bending, and Subversion in Ottoman Intellectual History (2017)

Networks: Zeyneb Hatun and Ayse Hubbi Hatun were also poets at this time, but ceased participating in poetry after marriage. She was also known to have close relations with Gülbahar Hatun, who was the mother of Bayezid II.

Clusters: woman poets (ex. Sappho), Turkish poets (ex. Mihri Müşfik Hanım).

less

III. Controversies

Controversy: There is controversy surrounding her love affairs. She wrote about her sexual desires for men. Although there is no evidence to support this, her poems may have been metaphors and imagined spaces. Some believe that she has copied many of Necati’s poems, a claim that warrants further investigation.

Feminism/social activism: Mihri’s existence at large was inherently an act of Feminism and Social Activism. In the Ottoman Empire, poetry was reserved for men. It was believed that both the lover and the beloved were positioned as male, with the beloved perceived as either a man or God. Poetry was commonly not written about women, because women were seen as coming between a man’s love for God. Poetry was meant to be performed in public. Since women were confined to the private domestic sphere, a public-facing woman was uncommon. As Didem Havlioglu states, “By simply being clear about her gender as a woman and doing something unexpected, such as composing love poetry for the beloved, she creates a rupture. When she uses this prestigious language and enters the literary space as a woman, it is no longer the same language or space.”

Issues with sources: The divan (archive of poems) consulted in this research, and the version referenced in numerous secondary sources, was written and interpreted by a male scholar, Dr. Mehmet Arslan. A question arises: Does his position as a man change how the work has been reinterpreted and delivered to the world? Mihri wrote in the Ottoman language, which borrows from Arabic and Persian. Mihris poems were translated from Ottoman to Turkish. It is essential to address the potential loss of meaning and context in this translation. Arslan presents readers with the language of the original poems, but then translates them and provides analyses in Turkish. Since the Ottoman language is not commonly practiced, it is difficult to determine whether the translation reflects what Mihri meant, particularly with respect to the period in which she lived. The language used at that time may not have had the same meaning as it does today.

less

IV. Bibliography

Primary Sources:

Havlioğlu, Didem. "On the margins and between the lines: Ottoman women poets from the fifteenth to the twentieth centuries," Turkish Historical Review, 1 (2010) 25-54.

Havlioğlu, Didem Z., and Mihri Hatun. Mihrî Hatun Performance, Gender-Bending, and Subversion in Ottoman Intellectual History. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 2017.

_____ (2006) “Naming the Beloved in Ottoman Turkish Gazel: The Case of İshak Çelebi (d . 1537/8),” in Ghazal as World Literature II. From a Literary Genre to a Great Tradition. The Ottoman Gazel in Context. ed. by in Angelika Neuwirth, et.al. Beiruter Texte und Studien 84. Beirut/Würzburg. 163-173

Archival resources:

Arslan, Mehmet. Mihri Hatun Divani. Ankara: Uyum Ajans.

Web resources:

http://www.biyografya.com/biyografi/9372

http://ekitap.kulturturizm.gov.tr/Eklenti/58679,mihri-hatun-divanipdf.pdf?0

http://ekitap.kulturturizm.gov.tr/TR-208575/mihri-hatun-divani.html

less

Bio

Meltem Saricicek is a multimedia artist based in New York who works with photography, video, performance, and textiles to investigate her hybrid identity as a Turkish American woman. In 2019, she received a BFA in Photography from Parsons School of Design at The New School.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully