Anyone visiting centenarian Julia Lobotsky knows to come bearing blueberry muffins. Having been alerted to her limited hearing and mindful of the effects of advanced age on short-term memory, I gingerly enter her room at the assisted living center and justify my presence by displaying a box of them. She is holding court from under a soft blue blanket atop a reclining chair, and the muffins are waved over to the kitchenette. I stack them atop the other boxes filled with baked offerings.

Julia is not a goddess, though if merit and vitality could a mythic figure make, she’d be in the running. 101 years-old with a blisteringly sharp mind, she’s critical in her initial perception of me. She asks repeatedly why I need more information from her. Did I not, she wonders aloud, do my research on the internet before coming? I assure her that I did, but my explanations don’t reach her as intended. After ten minutes of fruitless back and forth, during which I internally debate the most polite way to slink out, she says impatiently, “I think you just want to know what it was like back then!”

I’m relieved. This is exactly what I want to know. I’m not looking for answers to specific questions, though I have prepared a few. I would much rather be transported into the earlier eras of Julia's life by following the natural flow of her reminiscences. I answer affirmatively and she’s satisfied. “Why didn’t you just say so?” she asks.

She begins to speak about herself, weaving in and out of the decades of her life, peppering her stories with flecks of information collected along the way. The range is striking—from the history of Dutch settlements along the Hudson River to the mothers in her hometown who were taught to spot enemy aircraft in WWII. She describes the Japanese doctor she met in the 1950s who bemoaned the generation of short adults emerging from wartime malnutrition. He declared he was looking for a sizable wife to avoid short children of his own. Time had been on his side: the war ended right as he was been assigned to the Kamikaze. She tells me about the ad-hoc research she conducted on the dining service of the facility she’s in, about saving grease during the Depression to trade with the butcher for meat, about the superb evacuation plan of Washington’s Dulles International Airport, where she was when the towers were struck on 9/11. These are the stories, after all, that make up a life, and the breadth of hers is stunning. I settle in to listen.

*

Julia Lobotsky was born in Rhinebeck, New York in the summer of 1923. Her mother Mary had been forced to leave school at thirteen to help support her large family, finding work at a factory embroidering initials onto men’s handkerchiefs. Mary had had a difficult life, though her own mother’s had been even harder. Julia’s Grandmother left her first child in Czechoslovakia to cross the Atlantic and reunite with her first husband, who had emigrated earlier to work on the construction of the New York Central Rail-line. He had saved enough to pay her fare over and then died from work-related injuries, a common occurrence in those days, Julia tells me. Her grandmother did not find out about his death until she completed the treacherous crossing.

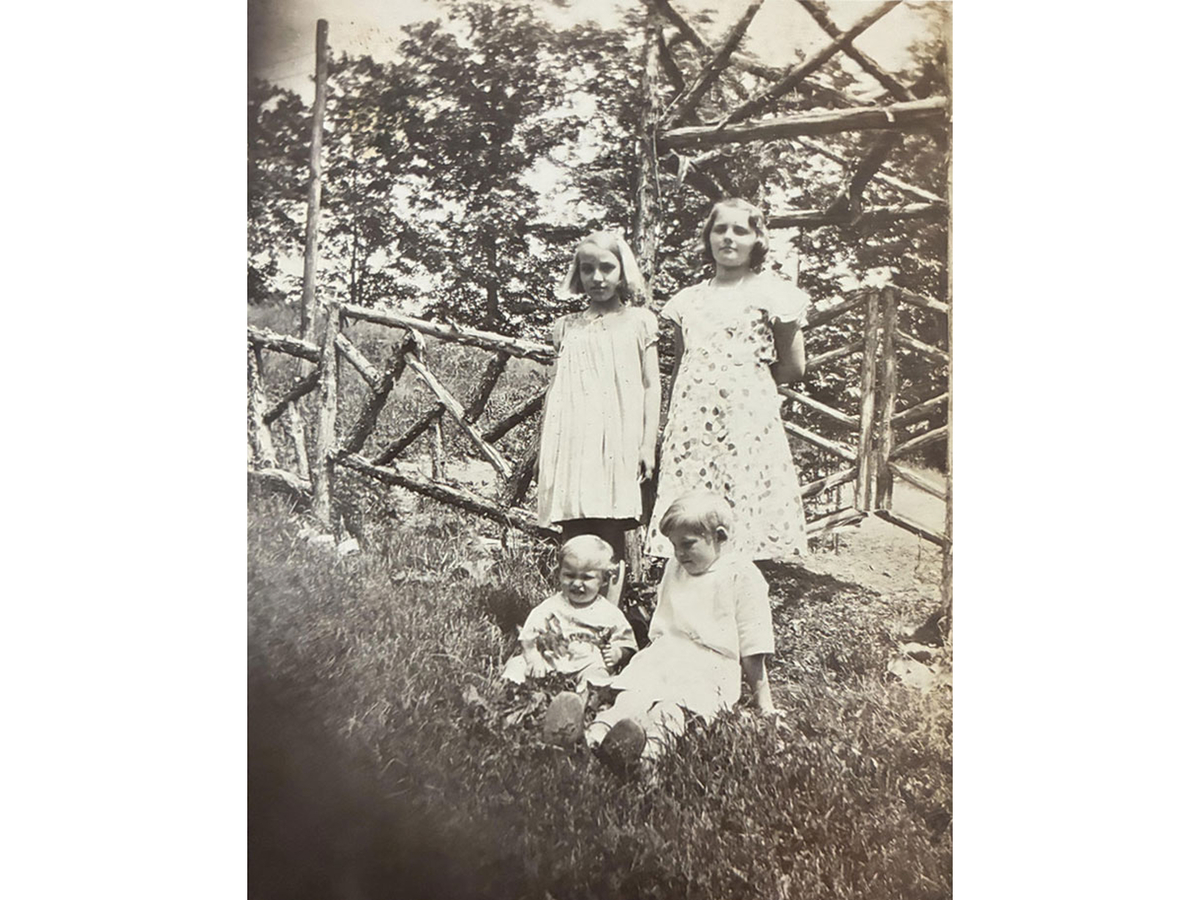

Julia’s grandmother then married one of the men who had delivered the news when she arrived, a friend of her deceased husband. He was also a rail worker who met a similarly tragic end, but not before her grandmother had bore numerous more children. Mary was the eldest from that second marriage. “This was before contraception,” Julia explained. “So everybody had families of about a dozen…once they got contraception, the next generation dropped down to about five, and so forth. It was wonderful.” Mary went on to have only four children of her own. Julia was her second daughter, followed by two sons.

Mary often spoke about regretting her truncated education, though she was pragmatic about the sacrifice. But one thing gnawed at her, and that was the lack of documentation regarding her birth. Julia recalled that Mary was frequently searching for information about herself. Back then there were no federal laws regulating birth reports; in the rural areas it was left to the churches to keep records. The railroad workers and their families were itinerant, living in caravans along the railroad and moving onward as construction advanced. Unfortunately, the church where Mary was likely registered had burned down, and with it the date and month of her birthday. Julia’s family had celebrated it sometime in October, but Mary continued to seek details of her past.

When Julia was young, she caught pneumonia several times before penicillin had been discovered. The illnesses left her with permanent lung damage and severe asthma. When she was well enough to attend school, her siblings would pull her the mile and a half to the aptly named White Schoolhouse on a sled or a wagon. There, the teacher recognized Julia’s early aptitude and often had her assist the younger kids with their learning. She remembers fondly the dictionary and the large encyclopedia in the back of the classroom, but very often she was sickly, and had to remain home.

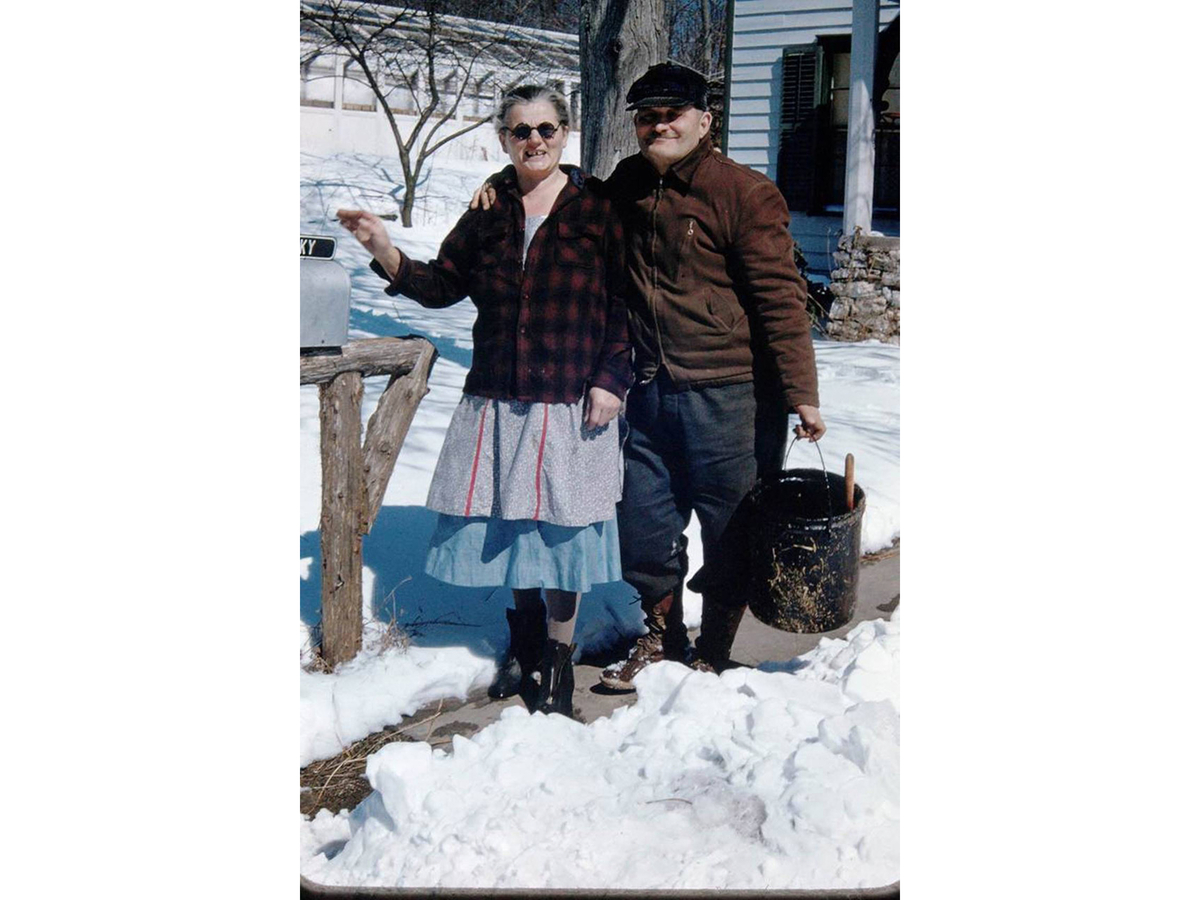

Her family of six lived on a farm they called Wonderland where they grew asparagus, a difficult crop, among other produce. Her father John was a kind-hearted refugee who had escaped czarist Russia under a wagonload of root vegetables. In addition to farming, he wrote poetry and short stories (later in life he would call himself a “revolutionary” and pen political letters to the newspapers). His cousin Peter had emigrated alongside him and helped build the family farm. During WWII, however, Peter made his way back to Europe to help smuggle Jews to safety. He was caught by the Nazis and burned down along with his operation. Peter was creative like his cousin John: a self-taught painter whose small, brightly-colored family portraits adorn a wall of Julia’s current room.

Autodidacts ran in the family. When Julia was forced to stay home from school, she would visit the neighboring farm where a woman named Gertrude Bailey and her husband lived. Gertrude had an extensive library with bookcases lining the walls and she invited Julia to borrow the books, which she eagerly did. She would take a book home one at a time and jot down in a notebook each unfamiliar word she came across. Pages became filled top to bottom with words that offered her an opportunity to discover what she did not yet know. In this way, word by word, Julia taught herself.

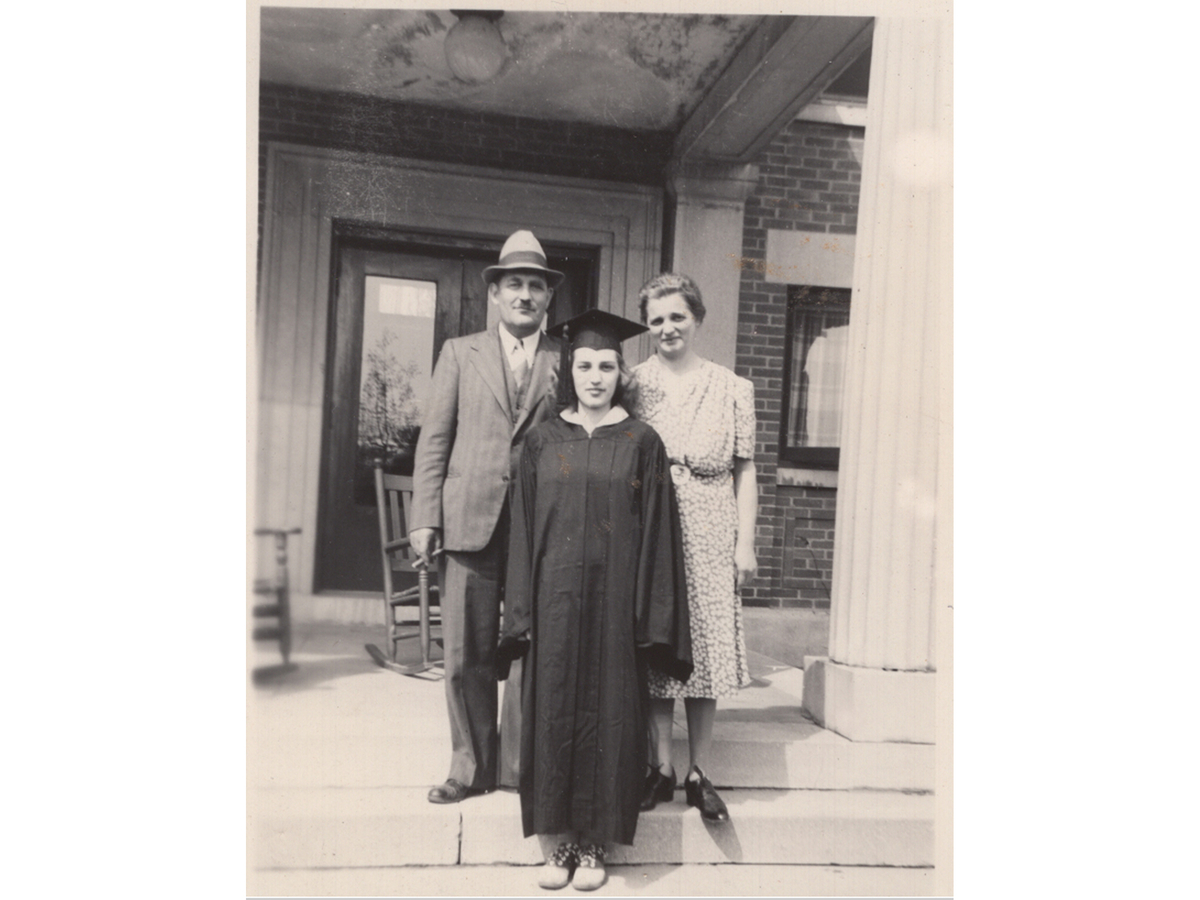

Her health improved and she attended Rhinebeck Central High School, graduating in 1939 just months before the Second World War broke out. As valedictorian of her class, she was awarded with a Regents scholarship from the state worth $100 toward further education. In those days girls who chose to go to college instead of or before marrying typically went to eighteen-month teaching programs. Julia’s parents initially wanted her to do the same. But Julia informed them that she did not want to teach; she wanted to learn. John seemed to understand this desire—he was an avid reader as well, gravitating toward biographies and philosophy. Mary, however, was worried and struggled to grasp what that would mean for Julia’s future, but neither parent ever tried to dissuade her from her intellectual pursuits.

As Julia would be the first in her family to attend college, the family sought advice from a Minister in Staatsburg. His daughter Betty attended Keuka College, a small liberal arts girls’ school about a four-and-a-half hour drive west of Wonderland Farm. As Julia tells it, a phone call was made to the school detailing her accomplishments and off she went. A similar occurrence happened later when she sought to further her studies at the University of Rochester. “Things don’t work like that anymore,“ she observes. “But they could if people had faith in each other!”

A theme that frequently arises as Julia recounts her life: achievements are not personal accomplishments but the result of the hard work and dedication of others. She likens all science to this collaborative effort, explaining that, “in Chemistry and Science, you can do things, because….nobody works alone, everyone [stands] on the shoulders of someone else.” She would discuss this when she was invited to give speeches, imploring listeners to take it upon themselves to help someone else along the way. She worries and laments that recent generations have become more self-focused and selfish, and when she speaks about her own education at Keuka College, she does so by remembering the women who supported her there.

First there was Dr. Flora Marion Lougee, the chemistry professor who “seduced” her with science. When Julia arrived at school she intended to study History, a subject she remains passionate about, but the “nice gentleman” who taught it appeared to have nothing new to teach the precocious teenager. She felt certain there was no future for her in the subject. But Dr. Lougee convinced her that she had a natural talent for chemistry, and Julia soon began assisting her. She remembers that as seniors, the young women chose to take an optional oral exam given by an outside professor, where all subjects in chemistry were fair game. They were full of nerves but wanted to impress their beloved professor and demonstrate how well she had taught them to push themselves.

There was also Ms. Hazel Ellis the Biology teacher, who had a little cottage on the lake, and on Saturdays would invite the girls for breakfast and birding. And most notably, there was Dr. Katherine Gillett Blyley, an English professor turned Dean who became the first female president of the college four years after Julia graduated. Katherine made an indelible impression on Julia, who described her multiple times as “magnificent” and “brilliant”. She was a tall woman with a penchant for blue silk dresses and heavy silver jewelry. She called Julia and the other students “her girls,” admonishing them not to sit at home but to go out into the world and do things. “This was not a woman you wanted to let down,” reflects Julia, and notes without bitterness that these women would have moved on to big universities or have become executives if only the opportunities had been available to them. “But that came later,” she adds.

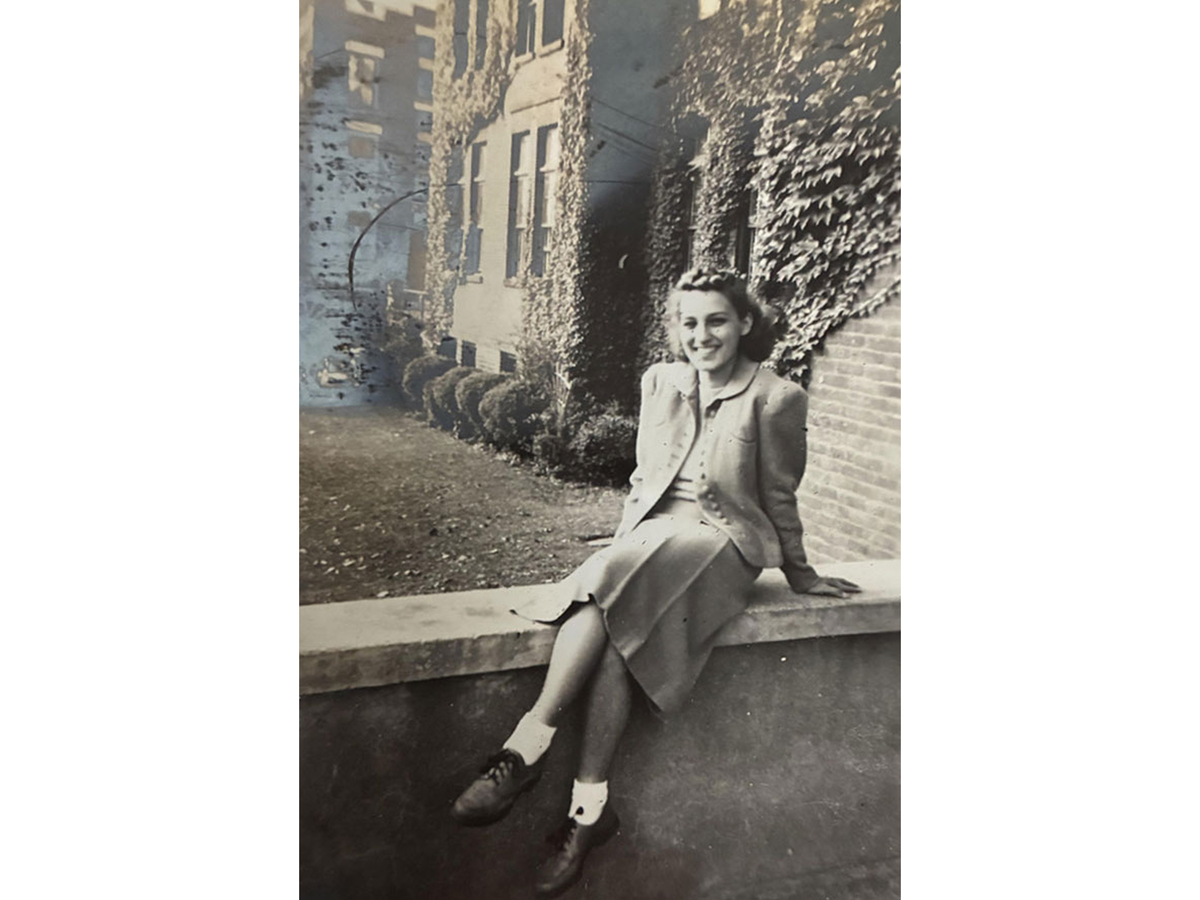

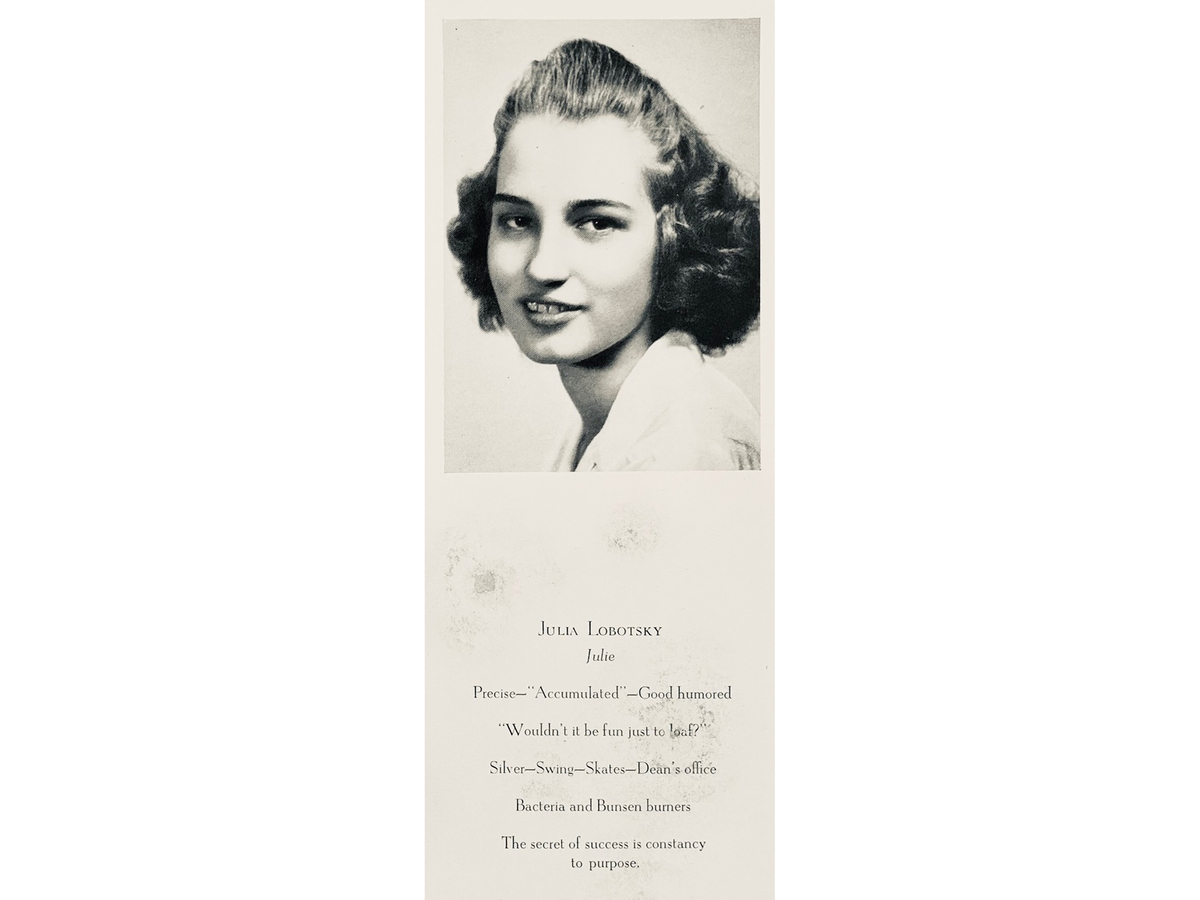

In Julia’s senior yearbook from Keuka, her favorite things at the time are listed as silver, swing, skates, Dean’s office. Just nineteen years old and in her final year of undergraduate studies, she gazes into the camera through dark, heavy-lidded eyes and a knowing, almost amused smile. There is something very soft about how she wears her youth, and even though the portraiture of the time bathed everyone in a sort of preternatural glow, the camera lends an especially ethereal radiance to Julia’s face. She is described (either by herself or observed by peers) as being Precise —‘Accumulated’—Good humored.

After graduating in 1943 as Salutatorian, magna cum laude, with a dual degree in Chemistry and Biology, Julia joined a fellow graduate at the American Cyanamid Research Laboratories, where she worked for a year as a Microbiology Assistant. The labs were located in Stamford, Connecticut and the two girls roomed on the ocean with a lovely but lonely woman who had taken over her father’s plumbing company. The landlady would serve them cereal and kugel with lemon slices for breakfast before they headed out six days a week to search for another penicillin. For three to four months, Julia searched for compounds that would inhibit bacteria, but soon felt she was stagnating—she had easily mastered the job’s necessary skills. This frustration led to an assignment on a different project within the company, where she tested the half-life of anti-staphylococcus drugs in mice. Just as before, Julia mastered the new skills quickly and came to the realization that these kinds of jobs were “dead-end roads” for her. She did not have the information needed to set up experiments herself and so she decided to go back to school.

Image source: https://www.keuka.edu/blog/keuka-college-spirit-strong-julia-lobotsky-43

As before, Julia remembers this transition happening seamlessly: she telephoned a friend who had gone directly on to the University of Rochester. This friend then called her mentor, told him about Julia, and he offered her a job and a scholarship. She spent two years there, culminating in a Masters of Science degree in Biology in 1946. An anecdote from that period: A unit of twenty WWII conscientious objectors, Julia tells me, were experimented on at the University by a professor who was interested in the effects of temperature on physiology. In the punishing cold of the Rochester winter, “you’d see [them] in their skivvies on the roof!” A dropped jaw betrays my thoughts and she clucks, assuring me no one had been seriously hurt, just, perhaps, “uncomfortable”.

After graduating, Julia was offered a fellowship by Dr. Walter Bloor, the professor and chairman of Biochemistry, whose work focused on the metabolism of fat. But in the 1940s women were not given a stipend for graduate work and Julia never considered asking her parents for help; she knew the struggles of farming and felt it was her responsibility to pay her own way. And after six years of school and work and the year of research in between, she was exhausted. At Rochester she had worked daily from 8 A.M. to midnight. Plus, by the end of the Masters program, money was so tight she skipped dinners the last week of every month. She had no choice but to decline Dr. Bloor’s offer and forgo the opportunity to earn a PhD.

*

When Julia talks, I contemplate what it means to survive as long as she has.

Seated on a folding chair next to her bed, we are surrounded by personal effects that have been whittled down over the years: fading pictures, photo gifts from family, bins of clothes and papers. Julia has lost countless friends, all her contemporaries, and finally, the last of her immediate family when her brother John died at the age of ninety-eight this past summer. They’d been very close, living together in his final years. Julia, in “good humor,” chuckles and recalls how his children had modernized his perfectly decent recliner. The new one was all but identical aside from six unlabeled buttons. More than once she had been across the room watching as he’d pressed the wrong one, slowly ejecting himself from the chair. He would call out each time, alarmed: “Julia, what’s happening?” Julia would tell him not to panic, he was just being slowly lowered down, and then she would call for help.

Along with the characters who have populated various eras, the objects that were once the fabric of our lives gradually begin to disappear with age. Even if we can attribute their absence to fate, the human life span, or a series of practical decisions made over many years, the reality remains: if we live long enough, our lives will shrink to something small enough to fit into a single room.

At least it looks like this on the outside. As tempting as it is for me—sixty years younger than Julia—to assume this external contraction reflects something internal, it just as reasonably stands that experience enriches the soul. Sitting with Julia I’m reminded of how much I like being in the presence of long-distance remembering. No matter the subject or emotional content of the stories she relays, each has a settled quality that demonstrates a deep acceptance within her. And it’s this acceptance, so often elusive when we’re younger and still in the thick of life, that offers a balm to its listener. It reminds us that while our beloved effects may fade away, that which hurt us will too.

At mid-life this is still difficult for me to conceptualize, though I do find myself getting closer to imagining it as an inevitability as the years pass. But I still cannot move far beyond the conviction that the peace I hear from Julia is merely a consolation to the mourning and loss ahead. Because someday—and this is if I’m “lucky”—what is left will no longer be the property of the physical world, but of the mind.

Perhaps that’s why for many of us, the threat of developing Alzheimer’s strikes a dark fear within our hearts. We seem to know instinctively that above all it is our memories that make and keep us who we are. And it’s alluring to use this fact to explain Julia’s incredible longevity. When appreciating the sheer quantity of episodic and semantic information she’s clocked in over her life and still has access to, it’s easy to see it as a kind of life force. She still seems to know exactly who she is.

*

After completing her studies at Rochester, a twenty-three year-old Julia rested for a bit at the family farm, luxuriating under the comfort of her mother’s nurturing wing. She then took a month-long appointment at a small place near Syracuse, NY, with a man looking to begin research in a former hospital. Julia cleaned and set up lab supplies for him before hearing from a fellow Rochester graduate. This friend knew a doctor who was setting up a lab in Syracuse. Dr. C.W. “Chuck” Lloyd was being brought on by the Obstetrics Department at Syracuse University School of Medicine and his lab was intended to function as a public service, providing assistance to women with various pregnancy difficulties. According to Julia, Chuck was the first full-time medical doctor to be hired by a university. Previously, medical schools had only hired working doctors part-time to lecture for interns. Julia met with Chuck and was quickly hired, holding her post as a Teaching and Research Assistant for the next sixteen years. Their work centered around reproductive endocrinology. It was a highly generative relationship for Julia: out of the forty-three scientific articles she co-authored during her career, she worked with Chuck on all but two.

Julia recalls women coming in with miscarriages in the fourth or fifth month of gestation. “We didn’t know anything about how to treat them,” she explains. “Because we didn’t know yet what the hormonal pattern was in pregnancy; that was primarily what the research was about.” She remembers the same women coming in repeatedly—up to nine times—with spontaneous abortions, some confiding that they would love to adopt instead, but their husbands would not allow it. Remnants of disbelief are present in Julia’s voice as she lingers on the thought of the continual suffering the women had been made to endure.

Another service performed by the lab was ectopic pregnancy testing. At the time there was no easy diagnostic tool for this often fatal condition, but if a woman had one-sided pelvic pain and a positive pregnancy test, a doctor could operate and save her life. Pregnancy tests were laborintensive and difficult to obtain back then, requiring that a woman’s twenty-four hour urine specimen be injected into a live animal. In Julia’s lab, young female rats were used. If the women’s urine contained what is now known as the pregnancy hormone hCG (hormone human chorionic gonadotropin) the dissected rats’ ovaries would be “nice and bright red”. This test was known as the Aschheim–Zondek reaction, developed in Berlin in the 1920s and performed on mice or rabbits. Later advancements led to the use of toads, and then eventually to home-test kits made available through new technology in the 1970s. Julia notes that the technology of modern testing is very simple, but that it takes time for these advancements to develop, underscoring again the collaborative nature of the researcher. “Nobody works by themselves!” she reiterates. Because the lab offered this important service seven days a week, only the extremely committed were given jobs. Julia was responsible for hiring the technicians and if they showed any hesitation about weekend shifts, she would send the applicants away. “You’re wasting our time,” she told them.

In 1962, Julia left Syracuse and followed Chuck to the Worcester Foundation for Biomedical Research Institute in Shrewsbury, Massachusetts. The foundation was established in 1944 by two brilliant researchers seeking freedom from the rules and regulations that accompanied University work. According to Julia, the foundation easily secured funds from pharmaceutical companies and the Ford Foundation, and this hotbed of explorative science is credited with fueling the advent of the oral contraceptive. Founder Gregory “Goody” Pincus and his lab-partner M.C. Chang had been continuing their “scandalous” work on in-vitro fertilization when they were approached at Worcester in 1951 by Planned Parenthood founder and birth-control activist Margaret Sanger. Sanger tasked the men with creating an oral contraceptive using funding from philanthropist Katherine McCormick, and they are widely credited as the fathers of the birth control pill, approved by the FDA in 1960 under the name Enovid.

Two years later Julia arrived on the scene as a Biochemist. She recalls how the contraceptive studies had been conducted internationally in order to circumvent U.S. regulations on human testing. Post-doctorates from other countries came to Worcester to be trained in technique and then went home to conduct the research and send their data back. This workaround continued during Julia’s time as well and she remembers training international researchers. She speaks glowingly of both Pincus and Chang, reminiscing pleasurably about her involvement in such a noteworthy era of scientific discovery. According to her, she received a phone call one day at work informing her that everyone was to meet in the auditorium. The call did not disappoint; once there, M.C. Chang showed the assembly of researchers the first ever video footage of an egg breaking the follicle and descending the fallopian tube. Another time she saw Margaret Sanger, by then an elderly woman, arrive in a limousine, bedecked with jewels.

In her last three years at Worcester, Julia served as the Editor for the newsletter Research In Prostaglandins. During this period Julia met fellow endocrinology researcher, Dr. Janet McArthur. A brilliant scientist, Janet worked at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School and would co-author 129 papers and two books over her long career. The two had a working relationship that evolved into a friendship and Julia talks warmly about her “wonderful friend”. Julia would work with Janet in the next part of her career as well, though in a different capacity.

As Julia tells it, after Pincus died suddenly of a rare blood cancer in the late 60s, money began to dry up at the foundation, and eventually she needed to move again to “secure [her] future”. Though the pharmaceutical companies had begun withdrawing research funding nationwide, public interest in the sciences had begun to skyrocket. “There was no NIH, there was no federal grant money for research…until we went to the moon in ‘69. Then suddenly there was a great interest in science…from the media to the public, and the public to their reps in congress and from money to do the research! That’s how it went,” Julia remembers. More funding meant more hiring, and in 1973 she was called by the National Institute of Health to set up an interview. Her first meeting was with a Texan, the temporary head of the reproductive unit. The unit consisted of only four or five men, and the Texan told her that he thought the job, which was administrative in nature, would be better suited for a woman. Julia bristled at his insinuation: “I thought to myself, boy, it’s gonna be a cool day before I come work for you.” But soon afterward the man was replaced and Julia was called in again. This time she felt there was compatibility between her and the new head and agreed to the position.

Julia’s official title at the NIH was Biologist—only PhD holders were designated as Scientists— but she worked as a Grant Writer. It was the “tremendous amount of writing” itself that drew her to the job, as she had always loved to write. Her department was within the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and she worked directly with researchers, assisting them with their proposals for funding. Her laboratory experience was essential to her effectiveness; she surmised that because her male colleagues had gone straight from school to government work they did not appreciate a lab’s reliance on its funds. Julia says that the men were lax about labs taking advantage of a loophole that doubled up their funding and did not care that this stole from other important research that could not, therefore, occur. Julia was not having this. By identifying the issue she helped fund thirteen more labs in the first year alone. Her boss came to rely upon her but regard from her co-workers soured; implicit to the story is that her own work performance put theirs to shame.

Nor was it pleasant being the only woman dealing with the Grant Committee itself. Julia was required to attend the meetings though was not allowed to speak beyond introducing herself. As such, the men ignored her, and she was appalled by their unchecked behavior. “I never heard such swearing and lousy language in my life…I didn’t understand how terrible people could be, how cruel! With no women on the committee…they would just make all sorts of nasty remarks”. She remembers a particularly cruel song they would sing about a woman from Galveston. The meetings upset Julia terribly, but fortunately the dynamic changed dramatically when a woman from California was added to the committee, reining in the men’s behavior.

Over Julia’s decades-long tenure at the NICHD, she was involved in six different task forces, including one on nutrition and another on genetics, and was a member of the Ovarian Workshop Committee. She recalls working on grants awarded to Dr. Shyamala Gopalan Harris for her breast cancer research, and remembers how Shyamala, Vice President Kamala Harris’s mother, would come into work on Saturdays with her two young daughters in tow. Julia also helped her good friend from Harvard, Janet McArthur, in securing funding for her own research. At that time, Julia and Janet were two of only about a dozen female members of The Endocrine Society —the oldest group of its kind and a leader in the field of hormonal research. The women were frustrated that they did not receive recognition for their contributions and were excluded from key roles within The Society. At a session in 1976, Janet gave a presentation mocking the low representation. This led to the formation of a group, Women in Endocrinology, and to Rosalyn Yalow being elected The Society’s first female president in 1978. Julia is proud but practical about the group’s accomplishments. “It shows you what women can do if they organize and figure out how to do it!” she says forcefully. “And you can do it; you can do more than you think!” She continues, “We need to get more women into government, into the congresses of the states, so they can look out for women, because evidently the men…are not going to stand up for what they know they need to do.”

Respect for Julia in her field was widespread. In 1990, she was awarded The Endocrine Society’s Lifetime Achievement Award, which praised her “tireless efforts in support of biomedical research” and her “unending empathy for investigators”. That same year she received The Society for The Study of Reproduction (SSR) Distinguished Service Award, “given to recognize ‘unselfish service’”. The chair of the SSR awards committee described Julia as:

an advocate, messenger, and advisor to many of us, [who] receives no personal recognition for our successes other than her own satisfaction in the knowledge that her efforts have advanced the field of reproductive biology” and noted that it was “her experience in the research laboratory [that] provided her with a strong commitment to excellence and the advancement of research…which has benefitted numerous members of the Society and reproductive biology as a whole.

In other words, Julia practiced what she preaches, first contributing directly to the body of scientific research and then supporting others in her grant-writing role so they could make contributions of their own.

In 1995, Julia was asked by the president of Keuka College to serve on the Board of Trustees. She was at first perplexed by the offer, having no real knowledge of undergraduate education. But at the first meeting she saw that there were few women and that the majority of trustees had neglected the Board’s fiscal responsibility. These were businessmen from nearby areas. “They put this on their letterhead, you know, ’trustee’…[but for them it was] just a big club. They were just having a good time.” She felt compelled to serve and the board benefitted from her sharp eye for nine years. Julia was awarded an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters by Keuka when she delivered the commencement address a few years later.

After twenty-five years of service and a difficult battle with colon cancer, Julia officially retired from the NIH in 1998 at the age of seventy-five. She was not ready to give up the pursuit of science, however. In her last week of work she phoned the Smithsonian in Washington D.C. and expressed an interest in teaching. The following Monday she began holding half-hour classes called The History of Science in America at the museum’s Hands-On Science Center, often for children on field trips. Julia was sometimes frustrated by the teachers’ disinterest, which she found was then mirrored by the children. Yet when she incorporated tactile and participatory elements into the experiments themselves, she saw that anyone’s curiosity could be sparked. For this reason, she was disheartened by the profit-driven changes she observed occurring during her time there, which steered the museum away from its educational purpose. Even so, she enjoyed the work and was sorry when she had to give it up thirteen years later, finding that the commute on the subway had finally become too exhausting.

*

Julia’s voice becomes fainter as the hours pass by, and it’s the only way I can ascertain that a large amount of time has elapsed. Aside from glancing over her belongings, my attention has stayed fixed on her face, animated and bright even at her age. She retains a sardonic humor and when she smiles, it is wide and luminous. In essence, she’s beguiling. I imagine she always has been. Though she insists she’s not too tired to continue, my conscience tells me otherwise. I do not depart satiated by her stories, instead finding it difficult to pull away and say goodbye. I could sit listening for hours more.

During our initial misunderstanding, I’d told Julia that I wondered what it had felt like to go to college when everyone else was getting married, about the misogyny she must have faced in a male-dominated field. Seeing her life through my own feminist lens, I told her I was there because of how impressed I was with all she had done and the rare life she had lived as a woman. She’d balked at this representation, telling me, “Life just happens. You don’t choose it…things happen!” I’d felt both shamed and puzzled by her resistance. Why did I see rebellion in her life choices where she only saw pragmatism or fate? And over the course of the afternoon, I attempted a few times but could not get her to tell me explicitly what it was that drew her into the field of reproductive endocrinology over all the other areas of science. Without her answer and despite her resistance, I can only draw inferences and see her as an unsung feminist hero in the historic struggle for parity between the sexes.

Whether or not she positions herself within a feminist framework, Julia has championed countless women and devoted nearly all of her adult life to expanding our understanding of the female hormonal system. The field of biomedical research has been unequal from its inception, with male bodies standing in as the norm. Women were excluded from clinical trials because of their “hormonal fluctuations”, leading them to be perceived as too unreliable for study. The NIH Revitalization Act of 1993, which came towards the end of Julia’s career, required that any research seeking funding from the NIH had to include women and minorities. However the earlier exclusion resulted in a massive lack of information that continues to cause a gender-gap in care today.

To achieve equality between the sexes, care and respect must be afforded to all bodies. Without people like Julia working tirelessly to prove the unique differences and needs of the female body, the NIH law and others like it might never have existed. It would be impossible to calculate how many lives have been improved or saved as a result of Julia’s contributions. In my futile attempt to grasp the enormity of this causality, I can only think of the so-called butterfly effect and imagine the millions of ripples that this single researcher’s wings have set in motion. Then again, as Julia has reminded me all afternoon, her work was made possible only through the contributions of those who came before her.

Despite the incredibly serious implications of her life’s work, Julia gives me a deceptively simple answer when I ask her why she chose to go into science: “Because you follow what you dream… what you want comes along, and it’s fun. Am I going to do something for [my] life’s work that isn’t fun?” I want something more from her response, want to understand what impelled this brilliant woman to work as long and hard as she did. Perhaps this reflects a generational difference in how we choose to think about our lives. But given her age, she’s earned the right to speak with authority. I reflect again that I’m witnessing the simplifying yet profound gift of distance. The prospect of sharing this perspective when I’m closer to Julia’s age flickers in my mind for a few seconds. But I see that I have much to do in the meantime. She assures me she will eat the muffins later as I say goodbye, and slip out the door.

Julia Lobotsky in 1990 (in frame), 2025.

Sources

Julia Lobotsky, ‘Curriculum Vitae.’

Julia Lobotsky, Interview, Conducted by Gina Walker, Sept. 2024

Julia Lobotsky, Interview, Conducted by Tamar Burrows, Nov. 30 2024

Julia Lobotsky, Interview, Conducted by Gina Walker and Tamar Burrows, Mar. 29th, 2025

Julia Lobotsky, ‘SSR Distinguished Service Award,’ Society for the Study of Reproduction, 1990. https://ssr.org/SSR/fbd87d69-d53f-458a-8220-829febdf990b/UploadedImages/Documents/Past_Award_Recipients/1990_lobotsky.pdf

John Lobotsky, Obituary, https://www.dapsonchestney.com/obituary/John-Lobotsky

Gretchen Parsells, ‘The Keuka College Spirit is Strong with Julia Lobotsky ’43,’ March 11, 2019, https://www.keuka.edu/blog/keuka-college-spirit-strong-julia-lobotsky-43

George S. Richardson, Fredric D. Frigoletto, Jr., Isaac Schiff, Beverly A. Bullen. ‘Janet Ward McArthur.’ Harvard Gazette, May 1, 2008. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2008/05/janet-ward-mcarthur/.

Lara V. Marks, ‘The Aschheim–Zondek Reaction: The First Hormonal Pregnancy Test.’ Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 107, no. 5 (May 2014): 192–93. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4275600/.

less

I. Personal Information

Name: Julia Lobotsky

Date and place of birth: July 28th, 1923, Rhinebeck, NY

Date and place of death: August 30th, 2025, Rhinebeck, NY

Family:

Mother: Mary (Stetz) Lobotsky

Father: John Lobotsky, Sr.

Marriage and Family Life:

Julia was the second of 4 children. She had an older sister, Nettie Lobotsky Brehm (September 24, 1921 – May 31, 2000), and two younger brothers, John (January 3, 1926 - June 19, 2024) and Walter (March 26, 1932 – Sept. 19, 2001). She never married or had children but has numerous nieces and nephews.

Education (short version):

Rhinebeck Central School (1939)

Bachelor of Science from Keuka College (1943)

Master of Science from the University of Rochester (1946)

Education (longer version):

Julia began her education as a young autodidact, as her severe asthma kept her home from school. She began borrowing books from a neighbor’s library, and every word she did not understand, she wrote in a notebook to later define, teaching herself. She graduated from Rhinebeck Central School in Rhinebeck, NY, at age 16, as valedictorian of her class, and won a New York State scholarship to further her education. The first of her family to attend college, she enrolled at Keuka, a small girls' school in New York. Entering first as a history student, she felt she already knew everything being taught on the subject, and was eager to expand her knowledge. A teacher noticed her aptitude for science and guided her into the field of chemistry. She graduated from Keuka in 1943, magna cum laude and salutatorian of her class, with a dual degree in Chemistry and Biology. After working for a year as a microbiology assistant at a Pharmaceutical House in Connecticut, she attended the University of Rochester, receiving a Master of Science in 1946. Julia was offered a fellowship by the Chairman of Biochemistry, but because women were not given stipends for graduate work at the time, she was unable to earn one officially.

Transformation(s):

Julia was driven by an insatiable curiosity, which found a natural home when she was introduced to the sciences in her undergraduate years. Throughout her long career and life, she was passionate about the reproductive sciences and maintained a keen interest in history.

less

II. Intellectual, Political, Social, and Cultural Significance

Works/Agency:

Julia was a biologist whose main field of study was Reproductive Endocrinology. After receiving her M.S. from the University of Rochester in 1946, she worked as a Teaching and Research Assistant in the Departments of Obstetrics and Biochemistry at Syracuse University School of Medicine for four years, from 1950 to 1962. While there, she helped provide early pregnancy tests to the public, which at the time was a laborious process involving urinalysis and rats. It was the only way to attribute abdominal pain to ectopic pregnancies, an often fatal condition if not immediately treated. From 1950 to 1962, she continued her role as a Teaching and Research Assistant in the Department of Obstetrics at the State University of New York Upstate Medical Center in Syracuse.

In 1962, she joined the Worcester Foundation for Experimental Biology as a biochemist; this center was founded by Gregory Pincus and Hudson Hoagland, and was where Pincus and physiologist MC Chang developed the oral contraceptive pill. Julia contributed to the ongoing research there, working on various aspects of adrenal androgen secretion and hirsutism. It was during this time that she met friend, colleague, and Harvard researcher Dr. Janet McArthur.

In 1973, she began working at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), in the Population and Reproduction Grants Branch of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). In 1979, she moved to the Reproductive Sciences Branch and became head of reproductive biology. She worked there primarily as a grant writer, helping other researchers secure funding for their research. It was during this time that she crossed paths with Shyamala Gopalan, the mother of Vice President Kamala Harris, and helped her secure grants for her breast cancer research.

Throughout her career, Julia co-authored forty-three scientific articles in Reproductive Endocrinology, many of which are available in the NIH archives, and from 1970 to 1973 she was editor of the newsletter “Research in Prostaglandins.” After twenty-five years at the NIH, Julia officially retired but continued working as a curator at the National Bead Museum and taught a History of Science course for the public at the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C., for thirteen years.

Reputation:

Julia received a Distinguished Service Award from the Society for the Study of Reproduction (SSR) in 1990, honoring her forty-plus years of commitment to the field of Reproductive Endocrinology; she was noted for the outsized role she played in supporting many other scientists in her field as their “advocate, messenger and advisor”. She received a Lifetime Achievement Award from The Endocrine Society, “in recognition of her tireless efforts in the support of biomedical research; relentless pursuit of excellence, and unending empathy for investigators”. She served on the Board of Trustees of Keuka College from 1994 to 2005, and in 2009, Keuka awarded her with an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters.

less

III. Clusters & Search Terms

Current Identification(s): Reproductive Endocrinologist, Biologist, Biochemist, Grant Writer

Search Terms: Reproductive endocrinologist, Shyamala Gopalan Harris, NICHD, NIH, SSR Distinguished Service Award, Society for the Study of Reproduction, Endocrine Society, Biologist, Scientist, Biochemist, Janet McArthur

less

IV. Bibliography

Sources

Primary (selected):

- Julia Lobotsky, ‘Curriculum Vitae.’

- Julia Lobotsky, Interview, Conducted by Gina Walker, Sept. 2024

- Julia Lobotsky, Interview, Conducted by Tamar Burrows, Nov. 30 2024

- Julia Lobotsky, Interview, Conducted by Gina Walker and Tamar Burrows, Mar. 29th, 2025

Web Resources (selected):

- Julia Lobotsky, ‘SSR Distinguished Service Award,’ Society for the Study of Reproduction, 1990. https://ssr.org/SSR/fbd87d69-d53f-458a-8220-829febdf990b/UploadedImages/Documents/Past_Award_Recipients/1990_lobotsky.pdf

- John Lobotsky, Obituary, https://www.dapsonchestney.com/obituary/John-Lobotsky

- Gretchen Parsells, ‘The Keuka College Spirit is Strong with Julia Lobotsky ’43,’ March 11, 2019, https://www.keuka.edu/blog/keuka-college-spirit-strong-julia-lobotsky-43

less

Bio

Tamar Burrows is a writer and night owl living in the bountiful Hudson Valley with her son. She is currently a student at The New School focusing on poetry, literature, and psychology. Her work explores the relationship between remembrance and self-liberation.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully