Though antithetical to the oft-presumed linearity of progress, there was a time when women played professional baseball, and that time has now passed. Baseball is considered to be America’s pastime for a reason, but during World War II, its future was rather dicey. Many men who played ball were sent overseas to fight, leading to a lack of players and a general fear that baseball would have to be put on hold until the war was over. The solution was to have women play professionally, and play they did. For eleven seasons, the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League employed women from all over the country, as well as Canada and Cuba, to play baseball professionally, just as men were. These women came from all different backgrounds and experiences - some even were still teenagers when they joined the league - and collectively inspired the nation not just because they were helping with the war effort, but because they were women and they played baseball well. Unfortunately, the league faced administrative and financial problems that led to its collapse in 1954, and though similar efforts were made to give women a place to play professional baseball, there has since been no other opportunity. Still, the inspiration provided by the women has been enough to demonstrate that women can and should play baseball, and even today, young girls look to the work done by the AAGPBL in order to know that they are just as capable of this professional athleticism as men are.

League Setup and Rules

As baseball grew in popularity in the early 20th century, thrown-together iterations of the sport also emerged. One of these iterations became softball, and it became a popular sport for all genders. Knowing that women were playing the game and also being aware of the crisis happening in men's baseball, Philip K. Wrigley founded the All-American Girls Softball League (AAGSBL).

The league was started as a nonprofit organization, both to keep out profit-driven owners and to establish the league with high respectability. After all, a women’s league was inevitably going to be looked down upon, so they felt it was necessary to frame the league as an emblem of community support and propriety. The desire for a wholesome image, however, did not end there. In the league’s inaugural year, every woman had to participate in a charm school, where they practiced manners and all other behavior associated with being “ladylike.” Not only did these rules police the women when they were on the field, but a plethora of them also applied to women when they were not playing as well. When they were not seen in uniform, the women were instructed to be in “feminine attire.” Even in their personal lives, the players had little agency over themselves and their image, despite the fact that many were well-grown women in their 20s. The women were not allowed to drink or smoke in public, they had to wear makeup, and possibly most famously, the uniforms they wore were skirted. In her book The Origins and History of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, Merrie A. Fidler describes the original uniforms in detail:

The AAGSBL uniforms designed by Mrs. Wrigley, Mr. Shepherd, and Miss Harnett consisted of a one-piece dress with a short, full, flared skirt. They were patterned after field hockey, tennis, and figure skating outfits then popular. These sports were generally the most socially acceptable for girls and women at that time. The original AAGSBL uniforms were made from pastel shades of green, blue, yellow, and peach, complimented by accessories of a darker shade of the same color.

Obviously, there was a goal in mind with these uniforms. The light pastels are nothing if not feminine, and though the uniform was based on other female athletic uniforms of the time - albeit, the ones for “socially acceptable” sports - baseball is quite different from those sports. In the sport of baseball, there is quite a bit of sliding, diving, and even an occasional collision.

Despite the fact that skirts were an unprecedented and highly impractical choice, they were used during all eleven seasons of play, likely despite strawberries (a sports injury characterized by large patches of torn skin, often from sliding) and other injuries that could have been avoidable if they had been allowed to wear pants. At the expense of player discomfort, they prioritized an image of perfect femininity. Still, the general consensus was that the women put up with the skirts because they had to, because otherwise, they could not play baseball. They were given a chance to play professional baseball - with the uniform stipulation - and they forged on because the opportunity was too good to pass up. Considering this opportunity does not exist today, it is likely that some women baseball players would wear the skirts right now if it meant they could play at a professional level. That does not mean, however, that the women of the AAGPBL did not complain. Famously, a scene in A League of Their Own features the women turning up their noses at the sight of the short skirts; according to Fidler, player Joyce Hill Westerman called the skirts embarrassing. To play baseball now in a skirt would be almost considered dangerous - but in 1943, it was a part of the deal.

less

Team Chaperones

Another misogynistic practice that actually ended up serving some good was having a team chaperone. These chaperones followed the team around, managed player behavior and wellbeing, and ultimately made sure that league rules and respectability were being adhered to. Despite the obvious double standard (after all, no men’s teams at the time had chaperones), chaperones were quite helpful to the players. After all, some of the youngest players were mere teenagers, as young as fifteen, who were probably scared to be thrown into a league of mostly adults. Additionally, even if the practice of having a chaperone is misogynistic today, it was fitting with the standards for young women at the time, as Fidler points out: “Their presence provided the opportunity to play professional ball to many 15 to 20 year olds who otherwise would have been kept at home by concerned parents.” Likely, the chaperones also provided a sense of feminine comfort that the male managers likely did not possess. The chaperones stood in as surrogate mothers, as they spent a lot of time with the women and they often faced many challenges on the road. It was also helpful to have an extra person to take care of the players, and chaperones ended up performing team physician duties, managing player injuries and determining when the women were once again ready for play. Overall, despite the misogynistic implication that women could not be trusted to look after themselves, the chaperones were highly beneficial to player life and wellbeing, and many players look back fondly on their memories with chaperones.

less

Public Reception

When the league was first established, many were not sure about what to think - to some, it seemed purely like a gimmick. Granted, women at the time were expected to make themselves look nice, not get dirty playing baseball. And though the league was in no way a gimmick, it was accused of selecting its players based on their looks, rather than their playing ability. This could perhaps be generalized misogyny - after all, according to this mindset, it seems as though one can only be conventionally attractive or a good ball player, but not both. But, it is important to note. The league was in a precarious position, doing what no other organization had done before, and it very quickly could have turned from an opportunity for female athletes into yet another place for women to have to perform femininity to the highest standards. It did not, though, and this is partly due to the players. Though they took their playing careers very seriously, the rules they valued slightly less so, following what they needed to and breaking a few whenever they could. Despite the women being highly aware of the feminine grace they were supposed to portray, they never let the league’s expectations for their image get in the way of their athleticism. After all, many of them came from rural backgrounds, where they grew up milking cows and riding horses - probably not bothered by details such as the straightness of their posture or the propriety of their hair.

less

Dorothy "Mickey" Maguire

Name(s): Dorothy McAplin (born), Dorothy Maguire, "Mickey" Maguire, Dorothy Maguire Chapman

Date and place of birth: November 21, 1918 in LaGrange, Ohio

Date and place of death: August 2, 1981 in Ohio

Education: Graduated from North Eaton High School in 1936

Siblings:

Stanley McAlpin - Brother

Elizabeth (Betty) McAlpin (Holland) - Sister

Mary McAlpin (Scofield) - Sister

Jean McAlpin (Cobb) - Sister

Michael McAlpin - Brother

Spouses:

Tom Maguire: The two were married during the start of Dorothy’s baseball career, but were divorced before the end of it. It has been said that he asked her to quit playing baseball, but because she was making good money, she refused.

George Chapman: They married in 1948, a year before Dorothy retired from baseball. The two had six children together, but eventually divorced in 1965.

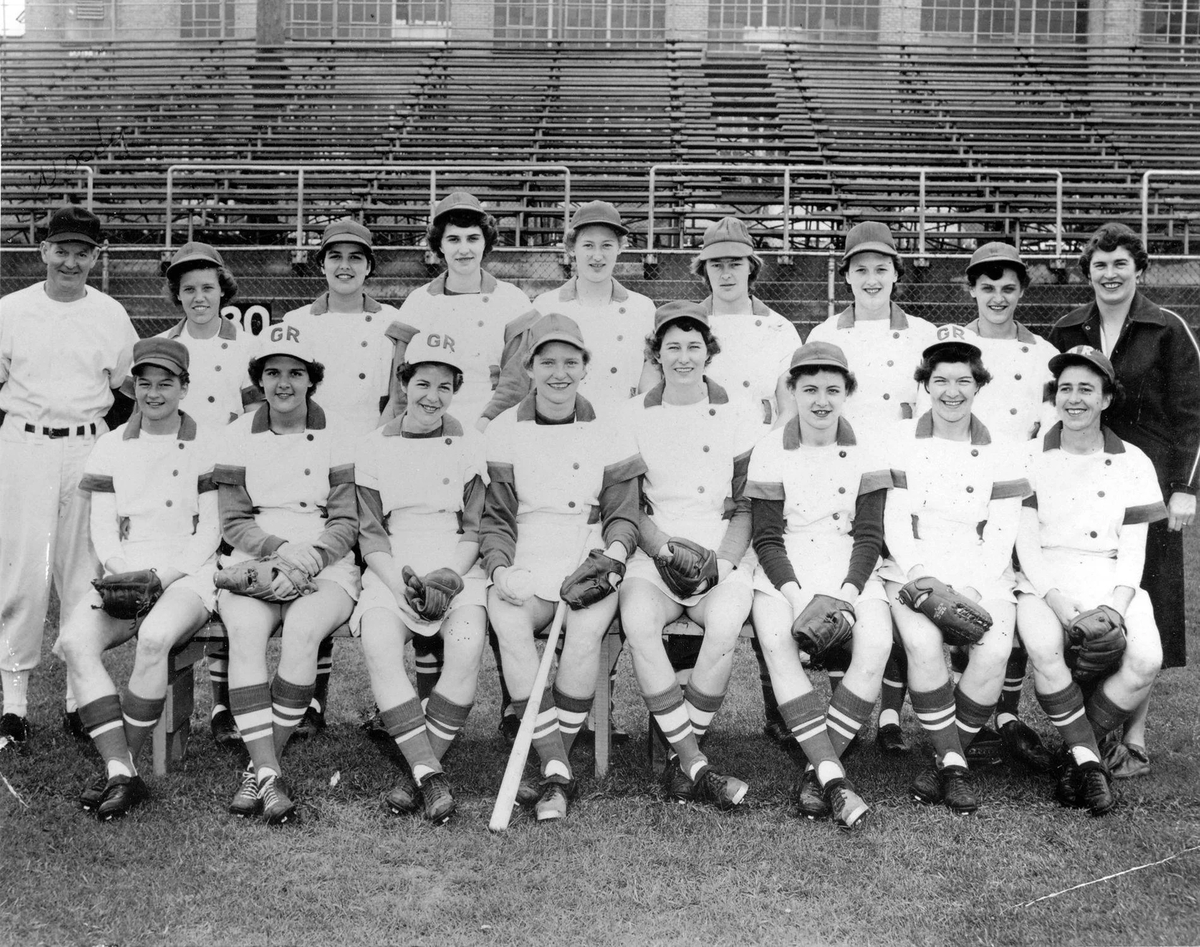

Dorothy Maguire was one of the original 60 members of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League. She played until 1949, where upon her retirement she was greeted with a standing ovation. During her career, she was a catcher for multiple teams, starting off strong with the 1943 Racine Belles, who were league champions that year. Again in 1944 for the Milwaukee Chicks and in 1947 for the Muskegon Lassies, Maguire helped lead her team to the championship title. Being an older and experienced player, Dorothy was reportedly one of the highest paid in the league. While playing baseball, Dorothy traveled to Cuba, where she participated in the league’s off-season exhibition games and got to experience things that she and most other women at the time otherwise could not have.

However, playing baseball was not always easy for Dorothy and the other women. In the league’s inaugural year, they determined that it would be necessary for each woman to participate in charm school, so that they could promote a “proper” feminine image. Seeing as Dorothy was a born and raised farm girl, this likely was not her cup of tea, but she and the other women endured these and other misogynistic practices because of the opportunity they were getting. Equipment was not made for women at the time, meaning that they had to rely on what was made for men and boys, and many doubted if these “girls” had any real playing ability at all. Still, Dorothy and the others proved them wrong, as the players were highly respected by many for their skills.

Dorothy grew up on a farm during the Depression, where she worked with a lot of animals. Eventually, she found a love for horses that lasted her entire life. As an adult, Dorothy did not mention her baseball career much at all. She taught her children to play, but when they asked her how she knew - “Because she’s a girl!” - she simply told them “I played ball.” Like many women at the time, Dorothy ended her formal education after high school. Her sports training, though, began from playing as a child, playing with her brothers and in girls’ leagues. She continued playing softball as she got older, which she did more formally for the Erin Brew team while she worked at the company. Because of this league, she had the chance to hone her skills and play even outside of the state, leading her to be an established softball player by the time of the league’s conception.

On June 10, 1944, Dorothy received word from her mother that her then-husband, Tom Maguire, had been killed in action overseas. Facing a double header that day, Dorothy chose to play, not telling anyone about Tom until after the games were played. This demonstrated an obvious commitment to her team and role as a professional baseball player, as she courageously took the field despite a great personal loss. A couple of months later, it was discovered that Tom actually was alive, just badly injured, though the couple eventually divorced. This story inspired a similar scene in A League of Their Own, as a player is notified of her husband’s passing via telegram right before a game. Though she, understandably, is taken away in tears, when that moment actually happened to Dorothy, she demonstrated her ever-present toughness in order to not leave her team hanging.

The word most often used to describe Dorothy is “tough.” As her sons Rick and George Chapman stated in an interview, she and the other women had to be, because not only were they just playing baseball, but they were also playing a huge role in the war effort. Dorothy was known for her spirited and determined nature of playing, even earning the nickname “Mickey” after Detroit Tigers Hall of Fame catcher, Mickey Cochrane; it is also said that her teammates called her “Indestructible.” Some opposing players even recalled that they were afraid to cross home plate when Dorothy was behind it. She was known for helping out the other players, especially as a catcher when the league transitioned its pitching style. Erma Bergman, a pitcher in the league, remarked to Rick Chapman that she would have quit had Dorothy, as a catcher, not helped her so much as she learned how to pitch.

Dorothy was one of the older players, which meant that she often helped out with chaperoning and coaching duties, aiding in the development of the younger players. However, she did not always act very “ladylike” on the field. According to stories from an umpire who was behind home plate with her, if Dorothy did not like a call, she would hold onto the ball for just a bit too long, letting him know that she was not pleased. On another occasion, she took a less subtle approach, stepping right on his shoe with her steel spikes. This, of course, is the nature of the world of sports, and Dorothy did not feel as though she had to shy away from her competitive nature just because she was a woman.

After baseball, Dorothy was quite well known in the Ohio horse sphere. She tamed a wild stud, Chico’s Flame, and he eventually became the Grand Champion of Ohio. Her tenacity, though, persisted throughout her life, as she was once kicked in the knee by a horse, which broke it. Despite being in a cast, she continued to show horses, just how she continued to play on through injuries and personal struggles. Dorothy died in 1981 when she was only 62 years old, meaning that she never got to see the revival of the league’s history with its first reunion in 1982 or the hit 1992 film that brought the league some recognition, A League of Their Own.

The July 1966 cover of Morgan Horse Magazine features Dorothy riding her horse, a testament to her reputation as an established and successful horsewoman. Dorothy is the star figure in the 2003 children’s book Mickey and Me by Dan Gutman. The book is part of the Baseball Card Adventure series, where a young baseball player named Joe Stoshack travels back in time to meet famous baseball players. In Mickey and Me, Joe intends to go see Mickey Mantle, but instead meets Mickey Maguire and other players in the AAGPBL. At the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, there is a statue dedicated to the women of the AAGPBL. The statue is called “Woman at Bat,” and it is based on a photograph taken of Dorothy’s batting stance. The statue was dedicated on May 14, 2006, which was also Mother’s Day. In 2010, Dorothy was inducted into the Ohio Women’s Hall of Fame for her accomplishments in the AAGPBL and as a horsewoman.

The All American Girls’s Professional Baseball League just celebrated its 82nd anniversary, though less than 50 of the original members are still alive. During the late 20th century, there was a re-emergence of the league’s history, with the first reunion taking place in 1982. The film A League of Their Own did much to bring forward the league’s history, but as of now, there is not a multitude of scholarship on the league. The All-American Girls Professional Baseball League Players Association works to maintain the league’s legacy with reunions and other archival endeavors. Though Dorothy died before the first reunion and subsequent establishment of the Players’ Association, it is the most prominent organization dedicated to keeping the league’s and players’ histories alive.

less

The AAGPBL's Impact

In an interview with Rick and George Chapman, they explained that Wrigley had connections within the midwest, and because there were a lot of defense plants scattered around making products for the war, the region was the perfect place to set up the league. The AAGPBL actually started as the AAGSBL, with four teams: the Racine Belles, Rockford Peaches, Kenosha Comets, and the South Bend Blue Sox. Eventually, the league expanded, though not tremendously. Despite the league’s size, though, they ended up being quite popular, even after World War II ended. Around the mid-1940s, attendance reached its peak, with a high of about 900,000 people attending games in a year. Despite what people might have thought when a women’s baseball league was announced, the women proved them wrong, all while playing good baseball and boosting community morale. In fact, these women played hard - they were tough, as Rick and George frequently reiterated. Somewhat thanklessly, these women joined the war effort to keep alive what mattered to America: sports and community. Though the impact of their efforts is hard to measure, it can be assured that they were not just providing entertainment but also hope and a needed sense of normalcy. Sometimes, all it took was a night at the ballpark to keep a person’s spirit alive, and when men were unable to step under the stadium lights, these women were.

Not only were the women of the AAGPBL enriching the lives of those around them, but through the league, their own lives were also being enriched through opportunities that would otherwise likely be unimaginable for a young woman in the 1940s. During the second half of the 1940s, the league did a lot of play in Latin America, especially Cuba. These exhibition games were quite popular, and the sight of American women playing baseball inspired Cuban women to form their own league, the Latin American Feminine Basebol League (LAFBBL). All it took was seeing other women play to know that they could do it also. With these games, Cuban talent ended up making its way onto AAGPBL teams, with 19-year-old Eulalia Gonzales, nicknamed “Viyalla” (the smart one), joining the Racine Belles as the first Cuban player in the league. More players from Cuba followed shortly after. The opportunities provided by these exhibition games were indescribable. Many of the players came from humble backgrounds where they would never imagine getting the chance to travel and interact with people from other cultures. These experiences likely shaped them and stuck with them throughout their entire lives, as travel outside of the country is a privilege to most, even now.

less

The End of Professional Women's Baseball

Unfortunately, the AAGPBL struggled with financial and administrative issues that eventually brought play to a halt. Throughout the league’s time, it went through multiple administrative structures, starting as a nonprofit under the Trustee Administration, then transitioning to the Management Corporation, until the decision to switch to independent team ownership that eventually brought down the league. When teams became independently owned, the league lost a lot of the practices that had once defined it. One of these practices was the unified spring training. From 1943 until 1948, the league trained collectively in one location. This provided a great opportunity for league unity, as well as socialization amongst players and other personnel. When ownership was left to manage each team and its training, it became individual. Not only did this probably personally impact players’ experiences, especially if they were used to reuniting with their peers every spring, but it also takes away a bit of the AAGPBL charm. Though the women were all fierce competitors, the teams collaborated with one another far more than is usual in professional sports. With the different exhibition tours and training opportunities, the women got to know each other even if they played on different teams. As a whole, the league functioned as a collective community, which seemed to break apart after they got rid of collective training and other travel opportunities. Additionally, at this time, financial matters were only getting worse, because the administration ignored the one thing that got the league going in the first place: publicity. As the league was taking off, it relied on ads, radio announcements, and other forms of publicity to spread the word. This was quite successful, but when thrown into financial struggles, the league was quick to cut spending for publicity and promotion. Attendance declined, and so did profits, and despite efforts to save it, the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League played its final season in 1954.

less

Looking Back, Moving Forward

Despite the fact that many who were involved with the league in some capacity are still alive, there is much to be desired in terms of scholarship and records concerning the league. Most of the players themselves continued on with their lives as though they were not professional athletes; they had kids, went to college, or got jobs that were a bit more ordinary than playing ball. Many told their stories when prompted, but only a few got the chance. It seems as though history largely forgot about the women who played baseball, though there are strong efforts being made to keep the league’s legacy alive. The first AAGPBL reunion was held in 1982, and they have been held annually since, complete with autographs, interviews, and, of course, the opportunity for old friends to catch up. 2023 marks the 80th anniversary of the league, and according to Rick and George, who also serve on the board of the AAGPBL Players’ Association, only a handful players are still able to make it. Soon enough, there will be a time when no players remain, and it will become the job of those who came after the league to work to preserve it. The Players’ Association, along with organizing the reunions, works with schools and museums like the History Museum in South Bend, Indiana and the National Baseball Hall of Fame to ensure that the legacy of the AAGPBL lives on. A good deal of hope was provided in 1992 when the film A League of Their Own was released. The movie is a fictionalized depiction of the 1943 AAGPBL season, and it captures the heart of the league and its inspiring women. Upon its release, many heard of the AAGPBL for the first time, and as younger generations hopefully continue to view the film, they too will learn that women played baseball and that history needs to be told.

less

The Hidden Powers of Professional Sports

The impacts of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League are hard to measure. At a time where many thought women ought to be in the home, these players showed that women ought to be on the field, in the stands, and in the labor force, just like men were. After either retiring or being forced to retire in 1954, many of the women used their earnings to pursue higher education. They became doctors, coaches, and teachers - and they might not have had that chance if they had not been making a salary playing baseball. These teams also created special networks of women who simultaneously shared similar experiences while also being introduced to people with lives far different than their own. To work and travel so closely with a core group of women is inevitably a beautiful opportunity for the blossoming of female friendships and camaraderie. Because while the women did have strict rules to adhere to, they certainly had fun. They played hard and played how they wanted to, breaking a little rule here and there to add in excitement. Some of the girls were so young when they joined that they practically grew up in the league - and what an amazing experience that is. Not held back by the traditional confines of female adolescence, they were able to travel, seek advice from older women, and form a community that was undeniably valuable during those teenage years. Female companionship is precious, and often underappreciated, meaning that there is minimal focus on the interpersonal relationships between the players in the existing scholarship. Still, these women were spending lots of time with one another, each connected by their love of baseball and the team families they now found themselves in.

The most important thing that the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League was able to accomplish was to show girls and women that they could play baseball too. It is evident from the founding of the Latin American Feminine Basebol League that sometimes all it takes is to see another woman playing to show a hesitant young athlete that she could also play ball professionally. There is a beauty in the reassurance of visibility - though these women likely did not doubt themselves before, they probably did not know that over in America, women were getting to play baseball. As soon as they found out, however, they knew it was something they could ask for, something they could achieve. This does not only apply to other female baseball players, either. In general, there was an increase in women in the workforce during World War II, but it appears that the AAGPBL might have played its own special role in labor force participation. When studying the relationship between women in the workforce and cities with AAGPBL teams, Margo Beck and Sarah LaLumia find that “the presence of an AAGPBL team is associated with a 1.8 percentage point increase in the female labor force participation rate, and with a 1.9 percentage point increase in the probability that a woman is employed.” Even if a woman did not play baseball, she still likely found herself inspired by the women and their simultaneous participation in the workforce and war effort. Now, if a woman wanted to work outside the home, but perhaps had an unmoving husband, she had yet another reason: the women of the AAGPBL are working, and they are doing mens’ work - is there any reason why she cannot do the same? Though less tangible than the other effects of the AAGPBL, the visibility given to these and other women athletes is infinitely beneficial, because even today, there is no opportunity for women to play baseball professionally. It is quite bizarre that 80 years ago, these women were given an opportunity that is nonexistent for women today. Though we like to imagine that the world today is more progressive than the one that existed in the past, things are not that easy. The first step towards professional women’s baseball in the 21st century is merely to call out the fact that women could somehow play professional ball in 1943, but not in 2023. This fact alone shows how relentless misogyny is, and how when something is given, it can certainly be taken away.

less

Remembering the League

Though it only existed for eleven years, the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League was a triumph. For the first time ever, women were playing the sport they loved and getting paid for it, much to the support of their fans, who very quickly learned just how talented these athletes were. Beginning as a response to the war-caused personnel problems in the men’s major leagues, the AAGPBL blossomed into its own sport with its own fan base that is still alive today. With an emphasis on community strength, these teams not only provided entertainment but also served their country in the best way that they could. Paving the way, the women of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League showed the world that women can knock one out of the park just as well as any man could. In a society that does not currently offer professional women’s baseball, sharing the history of the AAGPBL is crucial, so that when women ask to be able to play professional ball, they know that they are not asking for anything new or preposterous. Rather, we know that eighty years ago, sixty women from all over the country embarked on a journey to do what they loved - and they got paid for it. Though they did not know how people would react to them playing baseball as “girls,” their bravery demonstrates to us now that the world not just wants, but needs, the joy and brilliance of women’s baseball.

less

Update: The Women's Professional Baseball League is Ushering in a New Era for Women's Baseball

The Women’s Professional Baseball League proves that women’s baseball never truly ended, but was merely on hiatus. Co-founded by Justine Siegal and Keith Stein, the WPBL will launch its inaugural season in summer 2026. The seven-week season will consist of 7-inning games played at a central venue. Similar to the AAGPL’s first season, there will be four teams in 2026, but rather than the central cities selected for the AAGPBL, the chosen cities are coastal: New York, Boston, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. With expansion as the goal, the starting cities possess the four largest MLB consumer markets.

In another evocation of the AAGPBL’s opening season, the WPBL held initial tryouts in Washington, D.C., in August 2025. Over 600 women attended, and 130 athletes were eligible for the draft. Numerous prospects have already made waves, including catcher Hyeonah Kim and pitchers Mo’ne Davis, Rakyung Kim, Jaida Lee, Raine Padgham, Ayami Sato, Alli Schroder, and Kelsie Whitmore. The draft takes place on November 20, 2025, with prospective players fighting for one of approximately 15 spots available on each of the four teams. If selected, they will have the opportunity to play in the regular season, and the potential to participate in the playoffs and all-star game, which the league has already announced.

Despite a new name and setup, the Women’s Professional Baseball League acknowledges its deeply rooted history in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League. The all-female advisory board is led by honorary chair Maybelle Blair, who was an AAGPBL pitcher in 1948. After her time in the league, Blair played softball and became a strong advocate for women’s baseball, appearing in news outlets and leading multiple projects for the advancement of professional women’s baseball. She is set to throw the first pitch at the WPBL’s season opener in 2026 and stated, “We have been waiting 70 years for a women’s professional baseball league and it means so much for the girls.”

Blair is not the only league leader to acknowledge the AAGPBL. WPBL co-founder Dr. Justine Siegal said “I have so much respect for Maybelle and all of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League players. The All-American Girls Professional Baseball League set a precedent on what’s possible in women’s professional baseball. It is important to me, and the WPBL, that we honor the legacy and impact of their league while building a new future for today’s players who dream of playing professional baseball.”

In addition to Siegal’s remembrance of the AAGPBL, numerous news outlets, including the New York Times and the Associated Press, have included the league in their reporting on the WPBL. The New York Times called it “the second attempt at a women’s professional baseball league in the U.S.,” with the Associated Press referring to the league as “the first pro league for women since the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League.” As the two leagues’ histories become intertwined, the Women’s Professional Baseball League will hopefully find success and longevity, helping new generations learn about the women who paved the way for professional baseball.

less

Bibliography

Beck, Margo, and Sara LaLumia. “Female Role Models and Labor Force Participation: The Case of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League.” Eastern Economic Journal 48, no. 4 (June 30, 2022): 488–517. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41302-022-00219-w.

“Dorothy (McAlpin) Maguire & Chapman (,” n.d. https://aagpbl.org/profiles/dorothy-mcalpin-maguire-and-chapman-mickey/214.

Fee-Platt, Jordy. 2025. “Women’s Pro Baseball Is Here — and New York, Los Angeles Get the First Teams.” The Athletic, October 21, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/athletic/6734910/2025/10/21/womens-baseball-league-ny-la/.

Fidler, Merrie A. The Origins and History of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, 2006.

Ohio Women’s Hall of Fame. “2010 Inductee: Dorothy McAlpin Maguire Chapman,” August 26, 2010.

Stewart, Milo, Jr. “Woman at Bat.” n.d. “Woman at Bat” Statue Found in Cooper Park, Outside the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Thames, Alanis. 2025. “Women’s Pro Baseball League Selects Cities for Inaugural Season | AP News.” AP News. October 21, 2025. https://apnews.com/article/wpbl-womens-pro-baseball-league-66d5b97cb6ef7a9b0685b217c045baa2.

There’s No Place Like Kenosha. 2023. All-American Girls Professional Baseball League Players’ Association. https://aagpbl.org.

Wiles, Tim. “A Catcher’s Courage: AAGPBL’s Mickey Maguire Embodied Grace under Pressure.” National Baseball Hall of Fame, 2010. Accessed October 4, 2023. https://baseballhall.org/discover-more/history/catchers-courage.

WPBL Women’s Pro Baseball League. n.d. “WPBL: Women’s Pro Baseball League.” WPBL: Women’s Pro Baseball League. https://www.womensprobaseballleague.com/.

less

Bio

Emma Bauman is a recent graduate of The New School Eugene Lang College of Liberal Arts. She was the recipient of the Lang Ann Snitow award in 2025 and is dedicated to advocating for underrepresented voices in rural America.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully