Her name was Enheduanna. She was a high priestess, a writer, and a chronicler of her time. She is perhaps the first human author for whom we have a name, an image, and surviving texts. A she. Not Homer, Socrates, or Aristotle, as many are taught to believe, and as many have believed for millennia. Remember her name.

Enheduanna’s father was Sargon of Akkad, often credited with creating what is sometimes called history’s first empire. Sargon’s realm encompassed over sixty-five Sumerian city-states from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean, each with its own religion and administrative tradition. How could one man rule a world so fractured? The answer was a woman. Appointing his daughter as high priestess, Sargon hoped that her learning and eloquence would unite the empire. He was right. Enheduanna’s hymns to the goddess Inanna were so influential that scribes learned their craft for centuries after her death by copying her words.

First unearthed in the 1920s and translated into two more precise English translations fifty years later, Enheduanna’s texts are many things: devotional poems, political rhetoric, and, as it turns out, the earliest first-person account of sexual assault.1

“He has turned that temple into a house of ill repute. Forcing his way in as if he were an equal, he dared approach me in his lust! He made me walk a land of thorns. He took away the noble diadem of my holy office. He gave me a dagger: ‘This is just right for you,’ he said.”2

The very first known text written by a woman is, among other aspects, a story of rape. In the final line, her assailant’s words – “This is just right for you” – suggest that she should kill herself. Rape here becomes a weapon of annihilation, a means of stripping dignity and life itself. Centuries later, Lucretia would take that dagger literally, ending her own life after assault. For others like Christine de Pizan, suicide was not the only possible response. In The Book of the City of Ladies, de Pizan imagines three paths for women after rape: suicide, mourning, and justice. Her refusal of the traditional rape script, her insistence on agency, action, and speech, renders her writing startlingly relevant today.

Our earliest history classes teach children that the roots of “Western civilization” lie in ancient Greece and Rome. They are told to praise Plato, Ovid, and Aristotle. They read Homer (who, incidentally, may not have existed) and learn philosophy from Socrates. They read and reread the ancient myths, discuss them, watch them retold in film, restaged in paintings and plays.

But what don’t we talk about when we talk about history? We don’t talk about women. And we don’t talk about rape.

Demeter, Europa, Daphne, Persephone, Antiope, Hera, Leda. Philomela, Lucretia, the Sabines; remember their names. The specter of rape haunts Western civilization, and yet the history of rape remains largely unwritten. If there is no history of rape, has rape always existed? What does its persistence – and its erasure – tell us about the past? And what might we learn by seeking out its traces?

The history of rape is elusive; its evidence scattered and evasive. Most records come from male non-victims – ancient playwrights, medieval clerics, wartime chroniclers – but women’s voices are not entirely lost. We are only now beginning to rediscover them. These records also reveal that the stereotypes we hold about the past, namely, the belief that rape did not exist as a recognized category of violence and that the notion of consent held little to no significance, are false. Ancient Near Eastern laws and medieval court cases show otherwise. Rape was debated, legislated, and resisted. It is time to take this history seriously. Only then is a different future possible; one in which women are believed, and rape is not endured but eradicated.

Historicizing Rape

The dominant narrative of history insists that women have never held power. Feminist historiography exposes this as fiction. What happens when we view the past differently, restore women’s agency, and take their words at face value? History is not static; it is a living discourse. It can erase, but it can also resurrect.

Because there was no single word for “rape” until at least the fourteenth century, early accounts use euphemisms like abduction, seizure, or adultery, effectively disguising sexual violence. Misogynistic language shaped misogynistic memory. In literature, rape was often reimagined as seduction or desire—already present in Ovid’s Ars Amatoria and amplified in medieval romances and art:

“Never would a woman dare say with her own mouth what she desires so much; but it pleases her greatly when someone takes her against her will.”3

Christine de Pizan recoiled from this logic:

“I am troubled and grieved when men argue that many women want to be raped… It would be hard to believe that such great villainy is actually pleasant for them.”4

Six hundred years later, radical feminists Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon would say the same. Rape culture, they argued, not only enables sexual violence; it teaches us to eroticize it.

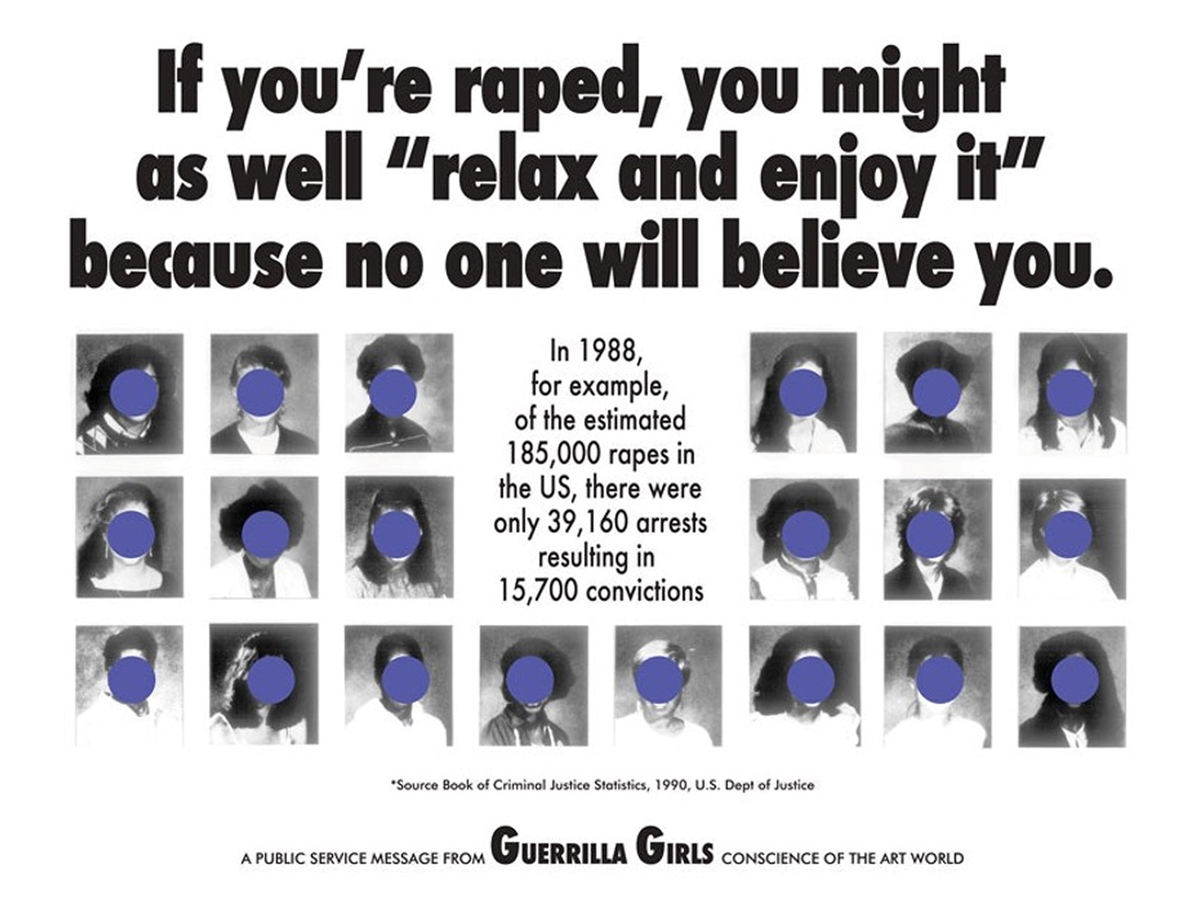

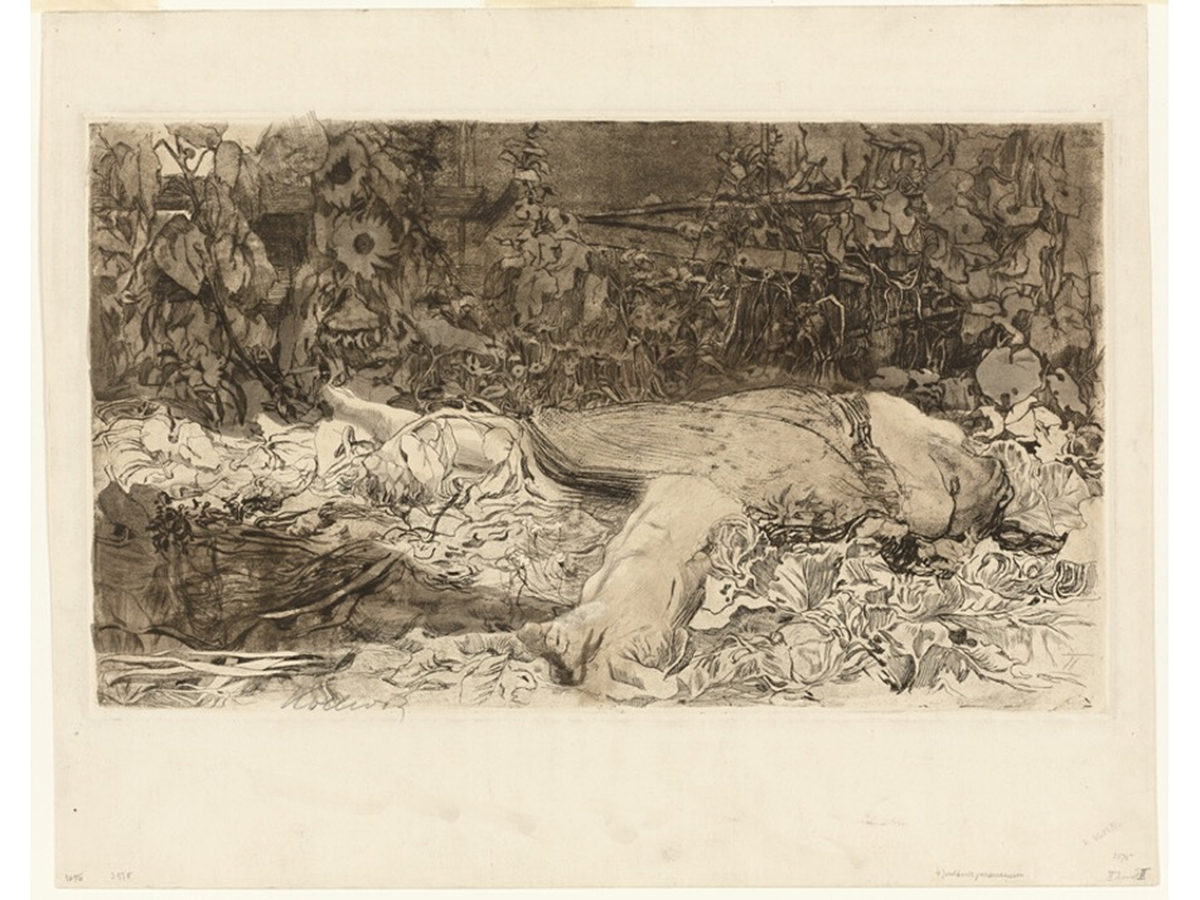

In 2014, Anastasia Powell and Nicola Henry defined rape culture as a network of beliefs and representations that normalize, excuse, or trivialize sexual violence. Art historian Macushla Robinson demonstrated its endurance in All the Rapes in the Met Museum (2021), analyzing 181 catalog entries where rape was aestheticized, never condemned.

As Lauren E. McCarthy and Gina Luria Walker argue, the sexual abuse of women is transhistorical and transcultural. From Margery Kempe’s fifteenth-century fears of nightly assault to contemporary headlines, the continuity is chilling. The language changes, the fear does not. Even medieval law reflects this ambivalence: though rape was punishable by castration or death, the legal and cultural loopholes were endless. Women were deemed lustful, deceitful, changeable; “real rape” required torn flesh, immediate outcry, identical retellings, and tears. In 1313, a woman named Joan accused “E.” of rape and became pregnant. The jury ruled her pregnancy proof of consent—“a miracle,” since “a child cannot be conceived without mutual desire.” Seven centuries later, U.S. politician Todd Akin echoed the same logic, claiming that in cases of “legitimate rape,” “the female body has ways to shut the whole thing down.”

As historian Barbara J. Baines observed, “Perhaps we think rape has no history because we mistake history for change. The legal history of rape, however, is the same old story.”

Resistance and the Right to Speak

And yet, the story is not only one of silence. Across centuries, women have found ways to resist, demand justice, and speak. In 1405, Isabella Gronowessone and her daughters ambushed Isabella’s rapist, castrated him, and were later pardoned. Christine de Pizan recounts the Galatian queen who beheaded her attacker. In the thirteenth-century case Plomet v. Worgan, Isabella Plomet sued her physician-rapist, won, and had him imprisoned. Marguerite de Carrouges insisted on a trial by combat in what became known as The Last Duel, risking her life for the truth. And in the seventeenth century, Artemisia Gentileschi brought her rapist to trial despite public humiliation, then transformed her trauma into art that shocks the viewer with vengeance and power.

Through her Judith Slaying Holofernes, Gentileschi paints not despair but defiance. Her voice and brush assert what history sought to suppress.

Why is narrativizing so essential? Because telling one’s story is itself a form of survival. As feminist theorists remind us, empowerment does not lie in reclaiming a “unified self” but in the act of narration. To study the history of rape, then, is to listen – to insist that women’s voices, long silenced, be heard on their own terms. It is to recognize that History as we know it belongs to men. But another history is possible: one written through women’s eyes and voices.

References

- There is an intimation of sexual violence in Jane Hirschfield’s translation of Enheduanna’s Hymn to Inanna. Forster’s translation likewise contains a reference to sexual violence: “A slobbered hand was laid across my honeyed mouth; what was fairest in my nature was turned to dirt.”

- Benjamin R. Foster, The Age of Agade: Inventing Empire in ancient Mesopotamia. London: Routledge, 2016; p. 334.

- Ovid quoted by Kathryn Gravdal in Ravishing Maidens: Writing Rape in Medieval French Literature and Law, p. 5.

- Christine de Pizan, The Book of the City of Ladies. Translated by Earl Jeffrey Richards. New York: Persea Books, 1998; p. 160–161.

less

Bibliography

Akard, Lucia. 2018. “A Medieval #MeToo.” The Public Medievalist. October 18, 2018. https://publicmedievalist.com/metoo/.

Baechle, Sarah, Carissa M. Harris, and Elizaveta Strakhov, eds. Rape Culture and Female Resistance in Late Medieval Literature. Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press, 2022.

Baines, Barbara J. “Effacing Rape in Early Modern Representation.” ELH 65, no. 1 (1998): 69–98.

Brownmiller, Susan. Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1975.

Chaucer, Geoffrey, and Sheila Fisher. The Selected Canterbury Tales: A New Verse Translation. New York: W.W. Norton & Co, 2012.

Cohen, Elizabeth S. “The Trials of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Rape as History.” The Sixteenth Century Journal 31, no. 1 (2000): 47–75.

Curran, Leo C. “Rape and Rape Victims In The Metamorphoses.” Arethusa 11, no. 1/2 (1978): 213–41.

Deacy, Susan, José Malheiro Magalhães, and Jean Zacharski Menzies. Revisiting Rape in Antiquity: Sexualized Violence in Greek and Roman Worlds. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2023.

Desmond, Marilynn, ed. Christine de Pizan and the Categories of Difference. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1998.

Georges Vigarello. A History of Rape: Sexual Violence in France from the 16th to the 20th Century. Cambridge: Polity, 2001.

Gravdal, Kathryn. Ravishing Maidens: Writing Rape in Medieval French Literature and Law. Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press, 1991.

Harris, Carissa. “‘For Rage’: Rape Survival, Women’s Anger, and Sisterhood in Chaucer’s Legend of Philomela.” The Chaucer Review 54, no. 3 (2019): 253–69.

Harris, Carissa. Obscene Pedagogies: Transgressive Talk and Sexual Education in Late Medieval Britain. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2018.

Harris, Carissa. “The Hypocrisies of Rape Culture Have Medieval Roots | Aeon Essays.” (2018) Aeon. https://aeon.co/essays/the-hypocrisies-of-rape-culture-have-medieval-roots.

Irigaray, Luce. The Sex Which Is Not One. Trans. Catherine Porter. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1985.

Lochrie, Karma, Peggy McCracken, and James A Schultz. Constructing Medieval Sexuality. Minnesota: University Of Minnesota Press, 1997.

Marder, Elissa. “Disarticulated Voices: Feminism and Philomela.” Hypatia 7, no. 2 (1992): 148–66.

Mardorossian, C. M. “Towards a new feminist theory of Rape.” Signs 27, no. 3 (2002): 743–775.

Matthes, Melissa M. The Rape of Lucretia and the Founding of Republics: Readings in Livy, Machiavelli, and Rousseau. Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press, 2000.

Powell, A., & Henry, N. “Framing sexual violence prevention: What does it mean to challenge a rape culture?” In N. Henry & A. Powell (eds.), Preventing sexual violence: Interdisciplinary approaches to overcoming a rape culture (pp. 1–21). London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

Scholz, Susanne. Sacred Witness: Rape in the Hebrew Bible. New York: Fortress Press, 2021.

Seabourne, Gwen. “Drugs, Deceit and Damage in Thirteenth-century Herefordshire: New Perspectives on Medieval Surgery, Sex and the Law,” Social History of Medicine 30, no. 2 (2017): 255–276.

Seabourne, Gwen. Women in the Medieval Common Law c.1200–1500. London: Routledge, 2021.

Winkler, Elizabeth. “The Struggle to Unearth the World’s First Author.” In The New Yorker, online first November 19, 2022. Accessible at: https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-struggle-to-unearth-the-worlds-first-author. Last accessed December 4, 2025.

Wolfthal, Diane. “Douleur Sur Toutes Autres’: Revisualizing the Rape Script in the Epistre Othea and the Cité Des Dames.” In Christine de Pizan and the Categories of Difference, edited by Marilynn Desmond, 41–70. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1998.

less

Bio

Maria Markiewicz is a writer, researcher, and curator exploring posthuman approaches to sexuality and relationality. Her work spans asexuality studies, critical posthumanities, and queer and feminist theory. She holds an MA in Contemporary Art Theory and a BA in Culture, Criticism, and Curation, and is currently completing an MA in Liberal Studies at The New School. Her publications include a chapter on posthumanist asexuality (Routledge, 2024), with forthcoming work on psychoanalysis and art (Routledge, 2026). Outside of academia, Maria is a founding member of the curatorial collective Post-Sexual Futures.

Comment

Your message was sent successfully