Somewhere, speaking under her breath in a bedroom two blocks or ten time zones away, a girl is asking a question, proposing a past, supposing a witch–her thought is her spell.

Tiktok has quickly emerged as debatably the most popular social media platform amongst children, teenagers, and young adults. Through its pithy and creative format, it has solidified itself as an enduring force of information. In contrast to the mulled over and slower pace of older platforms, such as Instagram and Facebook, Tiktok finds itself at the tip of the tongue.

Its very formula is uniquely breathless, pressed to the clock, to the present, running out of time to convey a message, joke, or tale that regardless of its content– feels urgent. Through an algorithm that meticulously braids highly-particular subcultures and communities, Tiktok reimagines early practices of storytelling: sharing news and daily-fables, with care, by word of mouth. Tiktok’s distinctive blackbox functions according to patterns in the language and names these subcommunities ascribe to themselves. The particular hashtag “Witchtok'' has seen 30.1 billion views to date, translating to millions of curious visitors. These numbers only skim the surface of this digital world. Seeing as much content goes untagged, this represents just the fraction of videos we are able to count.

Though October has always been a witch-centric month,“witchy-ness” permeating popular culture throughout the year is not a new concept. The early 2010’s saw the wisps of witch-like themes growing in our collective consciousness with the onset of American Horror Story’s Coven, crystals and divination decks in Urban Outfitters, pick-a-card tarot readings on youtube, and the burning of indigenous sage, a stolen and misused practice.

The draw of the ethereal is not a novel cultural ornament. However, beyond the continuation of these themes, something is drifting through the ether and reclaiming its realm: women of their own magic, wisdom as divination.

Witchtok provides a place to celebrate and bridge those who were and are condemned for possessing knowledge, or any practices that diverge from sleepy preordained world-perspectives and structures.

The origin of the word “witch” (much like the elusive individuals who have historically been marked by the term) is an enduring question mark. Without a complete picture of its composition, we must do what all New Historians do, we learn from its parts. Some elements around the term suggest connection to the Old English terms wigle and wih, meaning “divination” and “idol.” Others think there may be a possible beginning in the Proto-Germanic term wikkjaz, meaning necromancer, or one who wakes the dead, and the root weg, “to be strong, be lively.” Here is where we often find ourselves – waking and invoking those strong and lively voices of the past.

There is evidence to suggest that the original form of the witches name, “wicce,” may have had broader early meanings. If this is the case, somewhere down the line, magic and women were intertwined indefinitely and condemned as wicked. One of the earliest instances of this association can be found in the Laws of Ælfred (c. 890), more simply known as the “doom book.” The section writes: “Ða fæmnan þe gewuniað onfon gealdorcræftigan & scinlæcan & wiccan, ne læt þu ða libban.”

The important words from this fragment are the descriptors preceding “wiccan.” They are “gealdricge,” meaning a woman who practices incantations, and “scinlæce,” to mean a woman wizard or magician. “Scinlæce” derives from a root that means phantom or evil spirit, making it one of the earliest ghostly records in which witchcraft is designated a woman’s craft, and in its context, poisons this concept.

One other early connection between woman and the term witch comes from the word “Lybbestre,” which implies a sorceress with a proclivity for working with medicines or controlled substances. Witches were often historically women who transformed their pain and soothed the wounds of others. Local women who practiced early homeopathic medicine were often perceived as the utmost threat; the knowledge they harbored and the care with which they shared and protected it inspired fear, which later turned to violence. Witches teach us that knowledge is sacred, even to death's end. The alchemy of wisdom arises not just from within women, but when shared between women.

Our archive in this way could be classed as a coven, devoted to inventing new cauldrons of knowledge-ordering systems to hold every ounce of our elixir, incantations of our lineage, our grandmothers. The work of interpreting and imagining women from the past into the present is a part of our play. Thus, it feels only natural to join the conversation.

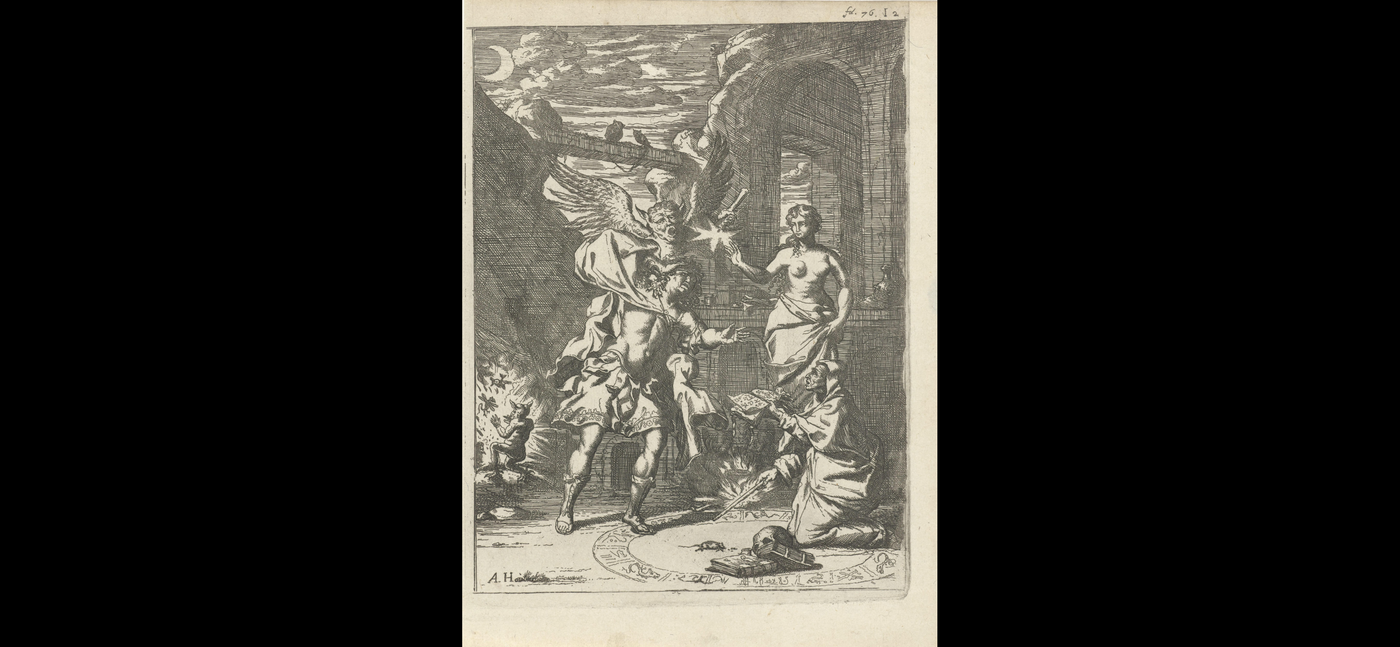

We set out to begin thinking about how we might visualize the witch as we regalled her tale. How do you dream of a famously elusive figure? How would you place the long protected and reclusive magic of a sorceress into the present of a New York City block? We often found her in the details: the brush of silvered branches against the dark, the gingerly glow of a waxing moon, a wintered street. To tell their stories visually, we considered the peculiar and gossamer thin line between what is mysterious and what is familiar. The witch past and present, more than anything, is an established bond of trust, a long hushed vow of secrecy. These are groups bound by their shared knowledge. Familiarity within these communities is imperative to protecting their past, and historically their very lives. From an outer perspective however, these groups are devoutly private and shrouded in lore.

To speak to this tension, we worked closely with both markers of mystery and allusions to close bonds. This was how the idea of “witch walks'' as a visual for the series first emerged. Contemplative and familiar at once–walking in the park with a friend. We turned later to featuring the exquisite wood relief portrayals of one of the early accused witches in Puritan New England, Tituba, created by New Historia artist Serra Kook. The indelible story of the sorceress carves herself into our time year after year like tree rings.

Many of the traditional markers of the witch are symbols of domesticity turned inside out. Out of the kitchen, the cauldron froths and brews a concoction of individual will, recipes of resistance. Cut from the wood of a laurel tree are brooms of flight rather than tools of servitude.

Through this series, we call upon a tradition of women who wanted to know, who were burned because they knew, consumed by the smother and cinder, by their weight of wondering– who knew the embers of their own eternity. May we never snuff their light.

Lauren E. McCarthy is a senior undergraduate student at Eugene Lang College of The New School, where she is pursuing a dual BA in psychology and literary studies. Her research focuses on thought and language mapping, memory organization in early childhood trauma, and interdisciplinary applications of neuroscience, as well as dissociation and comorbidity in the clinical realm. She works within The New Historia as an information-alchemist, using cognitive-minded spectacles to galvanize the data of the archive within public spaces.