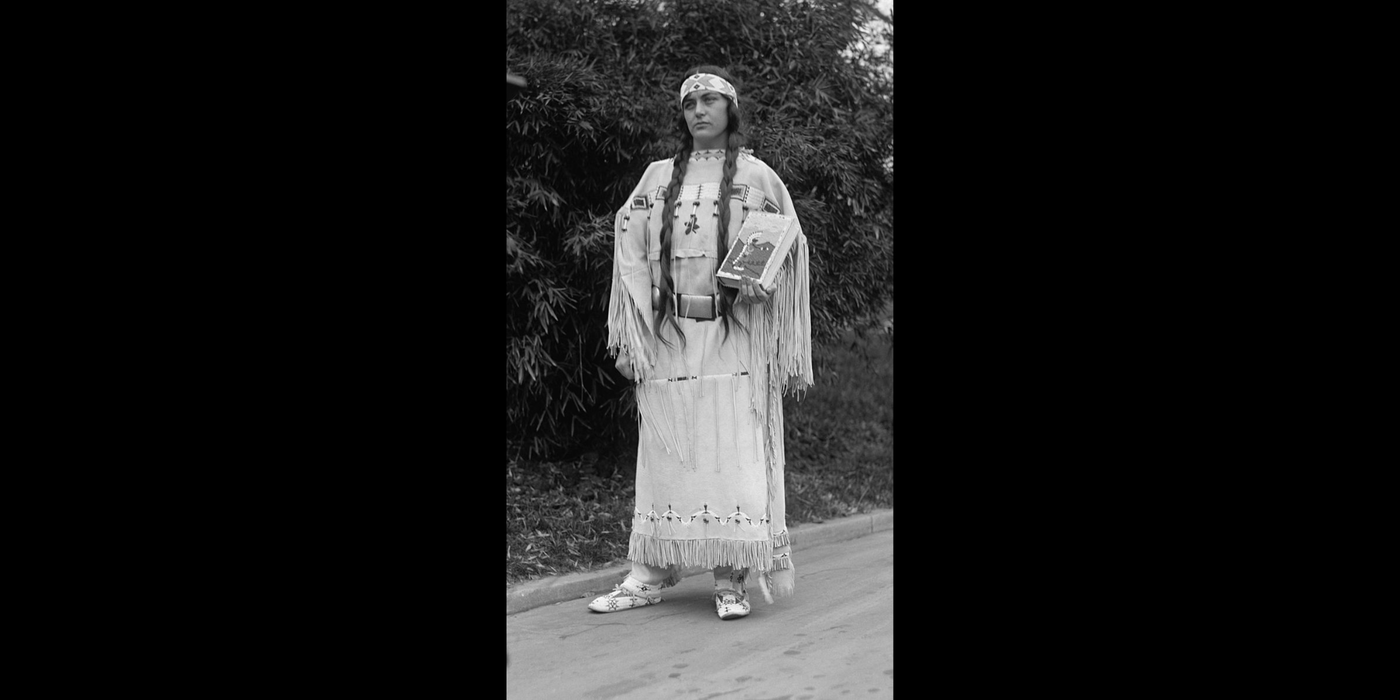

Ruth Muskrat Bronson (1897-1982) was a Cherokee author, educator, poet, and activist. Her short story, “The Serpent,” was brought to the attention of The New Historia by Nicole Richards, a student of Professor Gina Luria Walker’s, TNH’s Founder and Director, in her graduate course “Becoming Visible.”

“Becoming Visible,” like The New Historia, seeks to make the “missing matter” of history, meaning women, known and visible within the story of human culture. Students in this course not only learn about the essential contributions of women, but they take part in the recovery process themselves, restoring the fascinating accounts of individual women, including Ruth Muskrat Bronson.

“The Serpent” was written for the Mount Holyoke Monthly, a student publication at Mount Holyoke College, which is the women’s only liberal arts school where Muskrat Bronson was part of the class of 1925.

I

The old Cherokee woman sat stiff on the hard splint-bottom chair beside the outer door of the Indian Agent's office. Her hands lay motionless in her lap, folded one over the other on her faded calico apron. Her face was a deep network of wrinkles, seam on seam of hard brown skin. Her body was incredibly thin, so thin that she was only a little stooped wraith of a woman. Her eyes were tired and old. There was a vague baffled look in them. Only her chin and her erect shoulders seemed firm and resolute. It was as if her chin would defy the hopelessness that her eyes admitted.

She had been waiting on this same chair all the long morning. It was almost noon now, and still she did not force her way up to the Indian Agent's desk. All forenoon other Indians had passed through that door, crowded up to the desk, gained an audience and gone out again. A steady stream of Indians flowed past her, in and out. Still she waited.

At last the stenographer came up to the Indian Agent, sprawling in his swivel chair, his feet propped up among the litter of papers on his desk.

"Old Nancy Qualate has been sitting out in that office all morning. I think she wants to see you."

The Agent dropped his feet with an angry thud. A swift malignant gleam narrowed his slinky green eyes to mere slits in his long heavy face. His full, puffy underlip stuck out like a pouty child's.

"What does that old she-devil want with me now?" he raged at the stenographer. Bring her in here. I'll make quick work of her."

"Well," he bellowed at Nancy Qualate when the steographer had brought her in. "What do you think you want now?"

The old woman answered him patiently, halting over the unaccustomed English. "I no want my girl home from the school."

"Is that so !" The Agent was suddenly beside himself with anger. "That's just like you red skinned fools! You didn't want me to send her away in the first place, six years ago. Now you don't want her to come home." Suddenly he shot out his thick bull-like neck at her. "Why ?"

The old woman did not move. She did not take her eyes from his face. She had almost exhausted her supply of English, but she had her answer ready for him, fumbling it clumsily. "Educash." The words came haltingly from her tongue, as if she were experimenting with it, uncertain as to its meaning.

The Agent laughed harshly. "Education!" He laughed again. "You don't have the first conception of 'educash.' And further-more, it's a lie!" And he laughed in her face, a loud, harsh laugh.

The old woman did not flinch. Not once had she moved her position, nor shifted her eyes from his face. Now she only repeated her words again, patiently, flatly.

"I no want my girl home. I want her to the Government school."

"Well, you know how much good it does you to want!" he sneered at her. "I was down at the school the other day and I saw Lucinda. She's a big girl now, and a good looking girl, too.''

He rubbed his hands over his heavy chin with an air of complacent satisfaction. "And she ought to be home now, helping you-and Charlotte." His voice flickered out Charlotte's name maliciously. "And so, I have given orders for her to be sent home."

The old woman's hands clinched under her apron. That was all. Her face remained expressionless, unguessable. Her voice was swept clean of all emotion.

"I have said. I no want her brought home.''

"And I have said!" The Agent slammed his fist down on the desk. Books bounced from the jar of the blow. A paper weight rolled with a crash to the floor. "I've said that she comes home, and home she will come! I'm still boss on this reservation ! Now get out of here!" If his insolence had angered her, his domineering humiliated her, there was no one to know. With the same stern dignity, the same inscrutable expression, she turned and left the office. Stumbling, she groped her way through the dark hall and slowly hobbled down the stairs out into the street again.

The stenographer came into the room where the filing clerk was at work. Her face was white and drawn with anger.

"Sometimes," she said, her voice full of restrained anger, "I'd give my whole life to take a horse whip to J aim Roydan just once. He treats these Indians like they were dogs !" She pressed her hands to her temples. There were hot angry tears in her eyes.

"God, how I hate him!"

The filing clerk left her desk to come over to the window where the stenographer stood. "There's some others here that hates him as much as you do, if that's any comfort to you," she volunteered. "Do you reckon that if I didn't have to stay out here for my lungs I'd work for such a brute? You just wait." A distinctly cheerful note crept into her voice,-"somebody will stick a knife in his back some fine morning. They tell some pretty wild stories about him. Women, and-"

"Oh, he's got an eye for girls, all right," the stenographer cut in bitterly. "They say all over the Indian country there are dirty little half-breeds with the Roydan look stamped on them."

"Why don't the Gov'ment put him out of office?"

"Him? Huh. Ask the local politicians why he ain't put out of office. Ask the oil men. He's too useful where he is."

The girls were silent for a long time. The stenographer stood staring stiffly out of the window.

"What did old Nancy want? Was it about Charlotte?" this from the filing clerk.

"No, I guess it's too late for that. She didn't want Lucinda brought home from the school."

"Lucinda?" The filing clerk's voice was a mixture of surprise and comprehension, with an unclernote of horror. Then it flatted. "Charlotte was brought home three years ago, wasn't she?"

"Yes."

And again both girls fell silent, staring at each other.

II

In a way Lucinda Qualate was glad to come home from the Government school. It would be good to see her mother and Charlotte again. She wondered if her mother had changed in the six years she had been away from home. And Charlotte, the older sister she had been so proud of-it had been three long years since she had seen Charlotte. Yes, it was good to be coming home. Still, Lucinda could not help wishing the Indian Agent had let her finish her year at the Government School. And she wondered what sudden emergency had arisen at home that he thought she needed to come back to the reservation. Perhaps after a while she could go back again. Full of these thoughts and others like them she climbed clown out of the mail-car, lifted out her heavy suitcase and started off toward her mother's home.

Would she knock at the door and pretend she was some strange caller as she and Charlotte used to clo, or rush in and surprise them with her shout of greeting? She decided to knock. It would be such fun to play the old game over again with Charlotte.

Charlotte came to the door in answer to her knocking. Lucinda forgot her game of pretense and stood staring up at her. The change she saw in this older sister was startling. This was not the slender, imperious Charlotte who had left her at the school to come home three years ago. It was a stolid, changed Charlotte who stood holding the door open for her, a dull-faced Charlotte with a half-breed baby clinging to her skirts.

"Why, whose baby?" The words forced themselves from Lucinda.

"Mine." Charlotte's voice was sullen.

"Why Charlotte," Lucinda cried out reproachfully, "You didn't write me you were married!"

"I'm not," Charlotte answered her shortly, and turned toward the kitchen, leaving her standing with her suitcase m the open doorway.

"Lucinda," she heard her mother call, her voice as still and calm as if this were a thing which happened every day, "Is that you? Put your suitcase in the back bedroom and come on out here."

Dinner that evening was a nightmare, and all through the meal Lucinda sat and grieved at the change in Charlotte. Her mother seemed old, but then her mother had always been old, since she could remember. It was Charlotte that made it seem as if tragedy were stalking them all. Her tall proud elder sister! She was stolid and heavy now. And that baby! Lucinda could not force herself to touch it. She hated the green eyes that shifted and slinked up at her, and the odd mishapen mouth. She talked of everything she could think of to keep Charlotte from seeing that she noticed. And she tried hard to make the two of them smile. It seemed to her as if they had never laughed, as if all the springs of laughter in them had dried up. All the funny stories she remembered from school, and the jokes about the girls there whom Charlotte knew, she thought up and repeated. It was no use. The evening wore on, and Lucinda felt spent and tired, as if she had dragged some heavy burden across miles and miles of rough mountain road. She was glad when Charlotte took the baby to bed and she was left alone with her mother.

She wheeled on old Nancy. "Whose is it, mother?"

"The Agent's."

"Mother!" It was a stricken cry.

The old woman's voice went on, low, expressionless, and utterly weary, as if it must forever stay on this one level.

"And she's not the only Indian girl around here. The Indians are helpless. Charlotte was helpless." Her old eyes rested on her daughter's head like a hand laid there in blessing. Then they blazed with a sudden fierce glow. For one instant life woke in them and rebelled, then died; and her eyes added, from deep wells of pain, "you will be helpless, too." But her lips were silent.

"Oh," the girl's voice was desperate,-"why don't someone do something? Where's the chief? Why don't someone report him to the Government ?"

The old woman answered in her flat toneless voice. "There isn't anything anybody can do. The old Chief is blind and half paralyzed. Most of the young men who have grit enough to do anything have gone from the reservation. The Indians are just his property, like dogs. He's got the men of the state back of him. The Government won't believe an Indian against them."

"Then, why don't somebody kill him?" The girl's voice was bitter and hard.

Her mother was not startled. "They will, child, soon," she answered quietly, as if she were making a prophecy. "Now, go to bed. I will come in soon."

But Lucinda knew that it was far into the night before her mother knocked the ashes from her pipe and came in from the porch where she had been sitting, silently watching the black outline of the hills.

III

Lucinda had been at home a week when the letter from the Indian Agent came. It was a very short business letter, saying that she would have to come into Tahlequah the following Saturday to sign some papers that had to do with her allotment. He would come for her himself in the Government car. That was all. But it woke terror in the girl's heart and she rushed with it to her mother. Very carefully she translated it into Cherokee so that old Nancy might understand the whole of it. For a long time the old woman drawing slowly at her pipe did not answer.

Lucinda thought she had not understood. She read it again, more slowly.

"What does it mean, Mother?"

"It means you will have to go."

"I won't go!" Lucinda sprang up. Her eyes flashed defiance.

"I don't have to go. I am not a slave." Then she blurted out the thing she feared. "You know there are no papers to sign."

The old woman did not answer her.. She repeated it again, this time as a question, panic in her voice. "There are no papers to sign, mother?"

The old woman drew a long puff at her pipe before she answered. "No there are no papers to sign."

Then all the spirit left the girl, the terror overwhelmed her, and she dropped to the porch floor, catching at the old woman's knees. "Oh, mother, I won't go. I don't have to go, mother. Don't let me go!"

The old woman softly stroked her hair as she answered in her tired old voice: "I reckon you will have to go, child."

Three days until Saturday, then two, then only one. Like some caged thing waiting to be slaughtered Lucinda planned first one way of escape and then another. She would run away, leave the reservation. But where would she go? She knew what happened to Indian girls who found themselves in the white man's city without anyone to protect them. Where could she go ? And her mother, as if reading her thoughts, told her of Talina Wolfe's daughter who had tried to hide on the reservation. It was not a pleasant story.

The night before she was to start for Tahlequah Lucinda pressed the dress she was to wear. She took out her best pair of shoes and started polishing them. Her mother sat with Charlotte and the baby out on the porch. The baby played at Old Nancy's feet while she sat motionless and stiff, drawing at her pipe. Lucinda wondered whether her mother hated the baby as she did, whether now as she sat so motionless, she did not want to snatch up the child and fling it far out into the night. With the half polished shoe hugged in her lap, Lucinda put her head. on her knees and sobbed.

"Did you call me, Lucinda?" came the old woman's voice from the porch.

The girl forced the sobs deep back into her throat. "No, mother, I didn't call you."

IV

Saturday was a brilliant day. Lucinda, unable to sleep, was up almost at her and away from the house. About ten o'clock old Nancy returned. Her skirts were bedraggled and wet. Strings of the wet marsh-grass hung to her shoes.

"Why, mother, you have been to the marsh!" Lucinda exclaimed in astonishment. "Whatever did you go there for?"

Old Nancy did not answer her question. She made no sign that she had heard. She went to her chair on the porch, put the little covered basket that she carried down beside it, and drew out her pipe. Lucinda stood waiting in the doorway, irresolute. Finally she spoke.

"It is getting late, and the drive to Tahlequah is so long. We will be in the night if he does not come soon. We. can't make it before night now, can we, Mother?"

"No."

Again the girl hesitated. Then, "I would not like to be out in the night with him."

The old woman did not answer.

"Mother, there are no houses along that road, if-if-if the car should break down or anything happen. It would be terrible in the dark. Perhaps he will not come for me until tomorrow.

"He will come," the old woman answered her almost roughly.

"He came for Charlotte."

It was nearing sunset when he came. Old Nancy was sitting in her chair on the porch when he drove up to the house. She was so still that she might have been carved out of stone. She had been sitting like this all afternoon, ever since her return from the marshlands. Waiting-. Only the glow from her pipe showed that she moved or was alive. Close beside her chair on the porch sat the little covered basket.

Lucinda came to the door when the car drove into the yard. "Are you ready?" the Agent greeted her, paying no attention to old Nancy who answered him.

"It bees late too start so long journey over rough roads. Wait for morning. It bees too late now."

The Indian Agent laughed at her insolently. His greedy gaze took in the fair slender form of the Indian girl, it washed around her neat trim ankles, up over her firm sloping hips, up, up, until it rested greedily on the soft brown of her neck. The girl blushed painfully.

"I've been out later than this more than once," he answered the old woman. The rougher the roads the better. Get your hat, girl."

The old woman did not move. "You no will wait?"

"You know I will not wait," he sneered at her.

"Get your hat, child," she said to Lucinda, still not moving. Then as the girl turned into the house she saw her mother stoop to lift the small covered basket by her side.

It was a very little while that Lucinda was inside the cabin putting on her hat. When she came outside again, the Indian Agent was sprawled on the ground at the edge of the porch, clawing at his wrists and writhing in agony. And his whole body was beginning to swell with great puffy black swelling. Fastened around his wrists with a grip he could not claw free was a little yellow snake, the kind whose bite is instant death, and which, the Indians say, will not loosen its fangs from its victim until the sun has set. It was the little yellow Eet-o-wah found only in the Spavinaw marshlands.

On the porch the old Cherokee woman sat, still motionless and without expression on her seam-lined face. There was no sign that she had ever moved. She did not see the horrible writhing figure on the ground beneath her feet. Still puffing at her pipe she looked far off toward the Cherokee hills.

Ruth Muskrat, from the March 1925 issue of MOUNT HOLYOKE, page 160