Women writers have often endeavoured to create a historical archive of one another’s voices and achievements. Madeleine de Scudéry (1605–1701), alias Sapho (her salon name); Marie-Catherine Desjardins (1640–1683), alias Mme de Villedieu (her lover’s name); and Anne Louise Germaine de Staël-Holstein (1766–1817), née Necker, alias Mme de Staël, are among them.

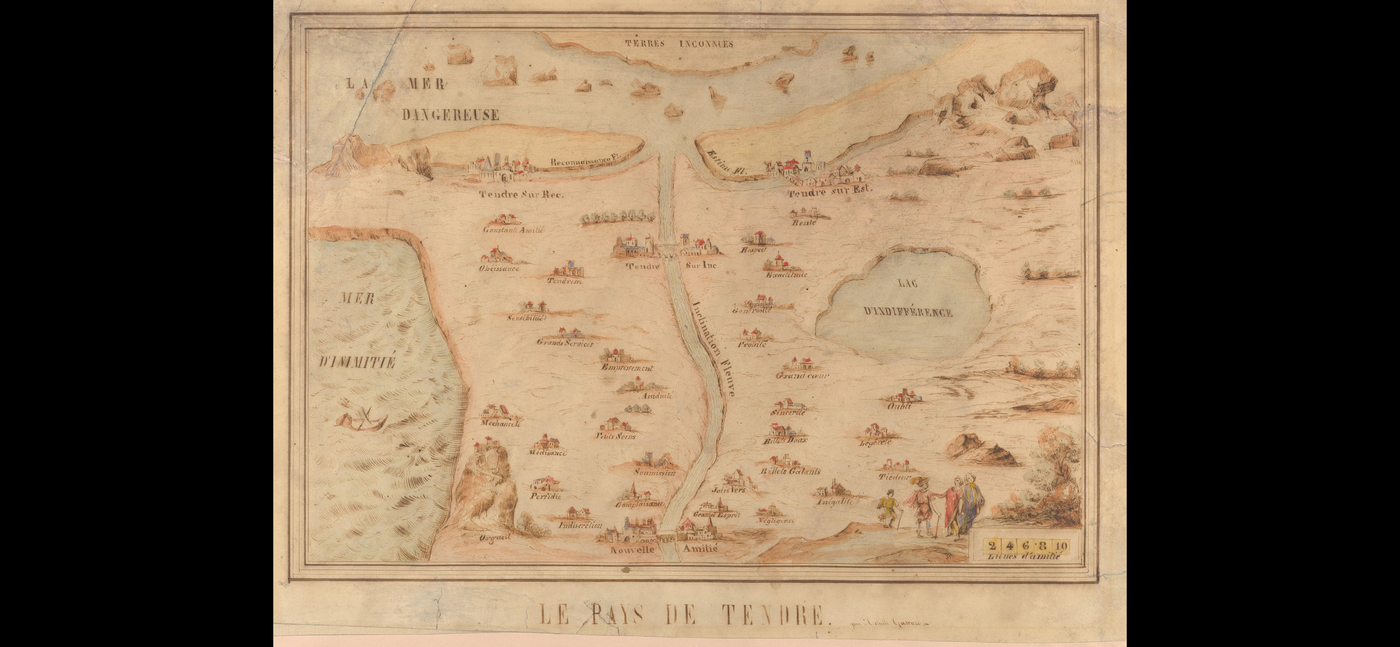

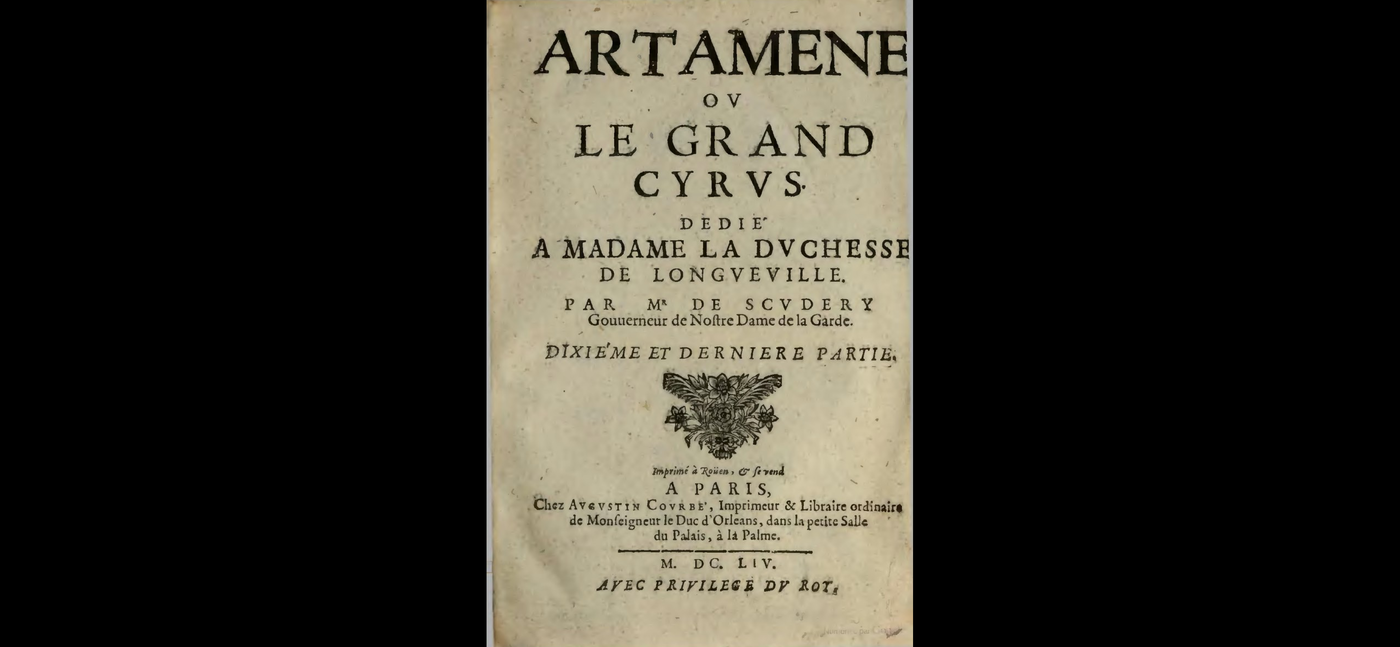

Madeleine de Scudéry became famous for her European best sellers, Artamène ou le Grand Cyrus (1649–53) and Clélie (1654–1661), the Harry Potters of the day, but she is now mainly remembered for her Carte de Tendre. This allegorical map of the human heart represents Scudéry’s philosophy on relationships, laying emphasis on mutual respect and equality of the sexes. The map embodies a new type of sociability, allowing women to be intellectually on a par with men.

Scudéry was at the heart of 17th-century intellectual life and was a great inspiration to her female contemporaries.

She corresponded with Catherine Descartes, Queen Christina of Sweden (her patron), Anna Maria van Schurman, and Sybille Ursula. As late as 1724, Madeleine-Angélique de Gomez testified to the far-reaching influence of Scudéry and the literary network she had set into motion: women writers like Villedieu, Lafayette, Murat, and D’Aulnoy had all gravitated around the literary queen.

Scudéry published under the name of her brother Georges, which has sparked some debate among scholars regarding, especially, the authorship of her earlier work Les Femmes Illustres (1642). Now widely accepted as coauthored by the two siblings, the collection presents speeches in which legendary women from antiquity tell their own stories. Sapho to Erinne, which closes the first volume, is remarkably innovative, shifting the focus from the traditional depiction of the strong woman warrior to that of the intellectual amazon. In this piece, Scudéry as Sapho urges women not to shy away from study, and to ensure they make one another’s names and talent known. This was the beginning of a literary career dedicated to her celebration of women. In her novels, Scudéry animates a constellation of female personalities, from queens to princesses and socialites, including Christina of Sweden and Ninon de Lenclos—both renowned for their intellect and unconventional ways of life.

In this hall of convex mirrors blurring the boundaries between reality and fiction, Scudéry’s contemporary, the poet Henriette de Coligny, Comtesse de La Suze (1618–1673), stands out. La Suze reinvented and refined the male-authored genre of the elegy. Her talent was immediately acknowledged and promoted by Scudéry, her close friend. In volume 8 of Clélie, Scudéry inserted an original European history of literature from antiquity up to the period in which she was writing her novel. This text ends with the prediction that La Suze “will write such beautiful, such passionate Elegies,” and “will excel all those who preceded her and all those who will strive to imitate her.” This is a notable example of a performative act, showing a woman writer consciously rewriting history by creating an archaeology of knowledge for her contemporaries to internalize and pass on to the next generations.

Two decades later, Villedieu includes an obituary for La Suze in her semi-fictional Mémoires de Henriette-Sylvie de Molière (1672–1674). La Suze is praised for her poetic genius. What’s more, Villedieu cites an unpublished elegy by La Suze, which she describes as “such a lovely and admirable piece.” The insertion of this real document in the midst of fictional news lends itself to a double interpretation. On the one hand, the elegy, which talks about the fear of one’s own sexual attraction to the opposite sex and criticizes the inconstancy of men, can be read as a way of portraying the fictional narrator’s life story as a historical document. On the other, making this elegy public, and thereby publishing it for the first time, is also a performative act whereby Villedieu endorses female authorship.

Like Scudéry, Villedieu uses her fiction as a way of archiving female knowledge and recording women’s voices—creating a sense of literary sisterhood in which women’s utterances are bound by similar experiences.

De Staël, in her novel Corinne ou l’Italie (1807), also creates a complex genealogy of connections, continuing the feminist work of Scudéry by extending it to a celebration of the Celtic female bards of Ossian’s epic. The commonalties between Scudéry’s and De Staël’s respective desires to revive women’s voices are striking. De Staël transforms Scudéry’s “prophetic dream” into a coronation scene—a poetic performance at the end of which the narrator states: “The same mythological images and allusions could have been addressed to all the women who have shone through their literary talent from the days of Sappho to our own.” Through this statement, De Staël emphasizes that her female character is not an exception; she belongs to a well-established cultural sisterhood of art.

Thus, when Simone de Beauvoir wrote in The Second Sex, “Mme de Staël fought for her own cause, rather than her sisters’,” she was to some extent still reliant on a masculinist narrative of women’s history. Had she, and Virginia Woolf before her, deciphered De Staël’s images and allusions to their foremothers, had they searched the archives to restore women’s voices into the official narrative, the history of feminism might have been a different one. Rewriting the literary history of women, and of feminism, is a task that involves not only detective work, but also connecting interweaving memories and keeping these memories alive for future generations of women and men. When Scudéry wrote her European literary history, she showed the way forward.

Séverine Genieys-Kirk is a lecturer in French at the University of Edinburgh, and has published widely on early modern women writers. She is the author of the forthcoming edited volume Recovering Women’s Past: New Epistemologies, New Ventures (Nebraska University Press) and is now working on her monograph, “Female-authored prose in early modern Europe (1500–1700): a cross-cultural study.”