More than 60 years ago, Rachel Carson published Silent Spring (1962) in which she sounded the alarm about the disasters chemical pesticides were wreaking on the planet – on birds, fish, plants, humans, and ecosystems. Carson was already a well-respected biologist and writer by the time Silent Spring appeared, having published two award-winning books, including The Sea Around Us (1951), which won the National Book prize in 1952. But Silent Spring catapulted Carson into public awareness in ways she had not anticipated: she testified before Congress about the dangers of using pesticides indiscriminately, stood her ground against the chemical industry that sought to discredit her work, earned the admiration and respect of President John F. Kennedy, and launched the environmental movement as it is understood today.

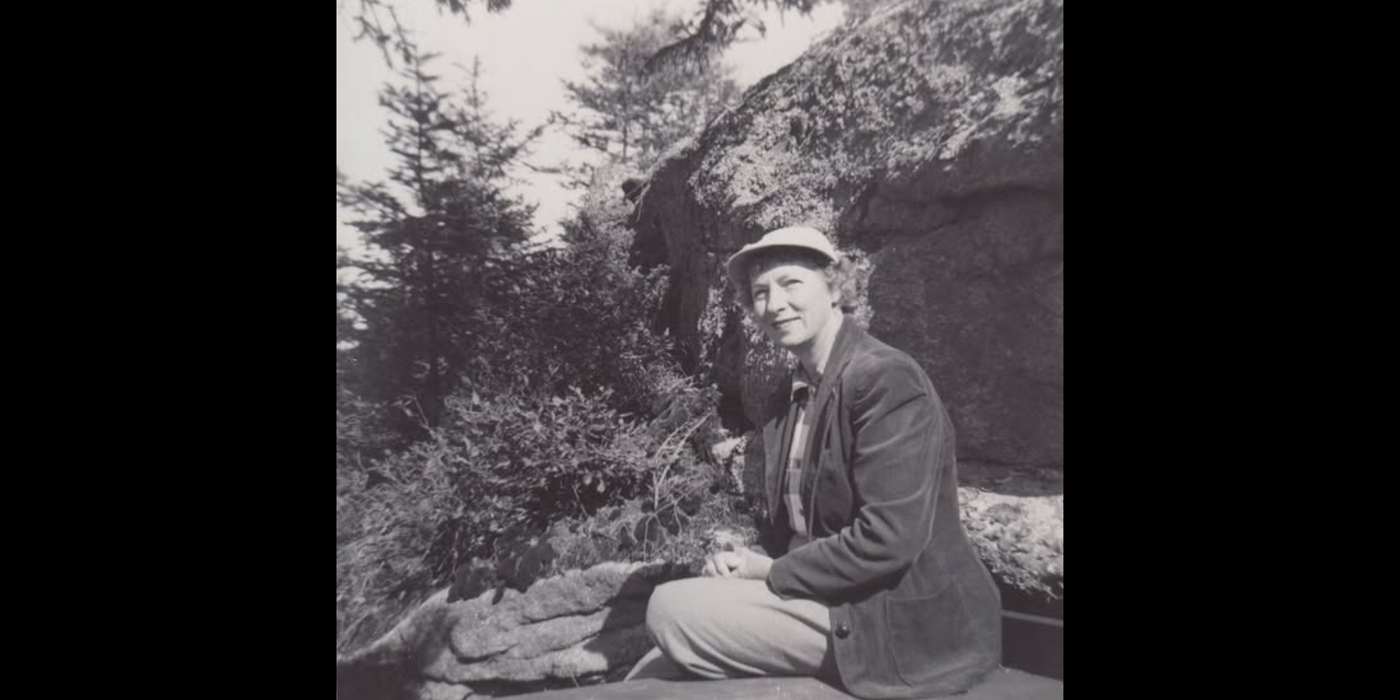

A photograph of Rachel Carson, c. 1940. Courtesy of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, via Wikimedia Commons.

Most accounts of Carson’s life correctly emphasize her training as a biologist, her work with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and her complicated family relationships. However, few accounts mention or explore the meaningful friendships she maintained with women – and men – and the role those friendships played in developing her views on the natural world. One such connection was her extraordinary friendship with Dorothy Freeman, whose summer cottage in Southport, Maine, was steps away from her own. Freeman provided encouragement and support for Carson’s writing projects and helped mold Carson’s understanding of the natural world in ways that mirrored the growth of their love, affection, and friendship for each other. As Lida Maxwell argues in Rachel Carson and the Power of Queer Love (2025), Carson’s insistence in Silent Spring on the wondrousness of the natural world grew out of the wondrousness of her relationship with Freeman. Had there been no Dorothy Freeman in Rachel Carson’s life, Silent Spring would likely not exist.

“Dorothy, Southport, October 1954,” photographed by Stanley Freeman Sr. in Always, Rachel, edited by Martha Freeman, Beacon Press (1995).

“Dorothy, Southport, October 1954,” photographed by Stanley Freeman Sr. in Always, Rachel, edited by Martha Freeman, Beacon Press (1995).

The remarkable friendship between these two women developed over twelve years, primarily in correspondence. Apart from their summers spent in Southport, Carson and Freeman seldom saw each other. Rather, it was through their daily letters that the two cultivated, nurtured, and celebrated their bond. Thanks to Dorothy Freeman’s granddaughter, Martha, who published hundreds of the letters written by Carson and Freeman (Always, Rachel: The Letters of Rachel Carson and Dorothy Freeman, 1952-1964 [1995]), readers have the privilege of observing – and even participating in – the beautiful friendship Carson and Freeman created.

Freeman and Carson were not drawn to the natural world as a mere object of investigation. Instead, they shared a way of being, an empathic existence through which each connected to the natural world. This mode of existence enabled them to experience nature as if they were one mind/body instead of two – that is, as if each were “another myself” – an expression Aristotle uses in the Nicomachean Ethics to define the “oneness” that characterizes genuine friendship.

In calling a friend “another myself,” Aristotle does not deny that friends may disagree or that they may offer alternative points of view to each other. What he is articulating – and what Carson and Freeman were experiencing – is an effortless, yet astounding, fluidity through which two people can partake of, or feel, or absorb some aspect of external reality – for example, beauty, or truth, or virtue – in the same way, as if they were the same person. It is only in friendships in their truest and best form, Aristotle argues, that this sort of “oneness” occurs.

Carson and Freeman each experienced the natural world as wondrous and awe-inspiring, and they each instantiated that wonder into their very being. Their enthusiasm and love of nature mirrored their enthusiasm and love for each other. No screen or veil ever stood between them; rather, their understanding of each other was immediate and direct. They experienced the world, too, directly and completely in tune with its wondrousness.

Rachel Carson and Dorothy Freeman, photographed by Stanley Freeman Sr. in Always, Rachel, edited by Martha Freeman, Beacon Press (1995).

Rachel Carson and Dorothy Freeman, photographed by Stanley Freeman Sr. in Always, Rachel, edited by Martha Freeman, Beacon Press (1995).

In an expression of mutual gratitude, Carson wrote to Freeman in 1955: “The one thing I wish today above all else is that as the years pass we may never come to take for granted this beautiful sympathy and understanding that exists between us, but may always feel their shining wonder as we do today” (Always, Rachel, 125). Freeman wrote to Carson four years later: “It has always seemed some kind of miracle that after over fifty years of living someone I had never known could come to hold such a unique place in my life. The first amazement is still in my heart” (Always, Rachel, 204).

The friendship between Carson and Freeman was beautiful and rare; a friendship certainly worth emulating, savoring, and celebrating. It was also incredibly powerful, giving Carson the ideas, the language, and the confidence to say, in Silent Spring, what needed to be said.

Nancy Kendrick is Professor Emerita of Philosophy at Wheaton College, Norton, MA, and Philosopher-in-Residence at The New Historia. She is co-author with Jessica Gordon-Roth of Early Modern Epistemic Injustice Theory: A New History (forthcoming).